Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study is to synthesise evidence for the experiences and perceptions of incivility during clinical education of nursing students.

Design

We used a meta-aggregation approach to conduct a systematic review of qualitative studies.

Data sources

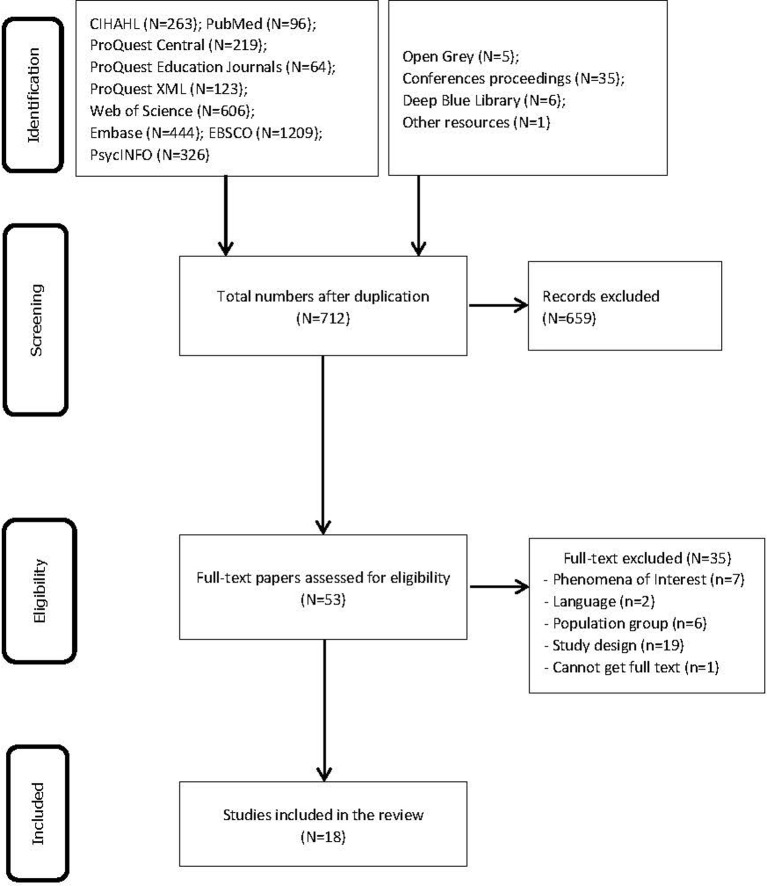

Published and unpublished papers from 1990 until 13 January 2018 were searched using electronic databases, including CINAHL, PubMed (MEDLINE), ProQuest Central, ProQuest Education Journals, ProQuest XML-Dissertations and Theses, Web of Science, Embase, EBSCO Discovery Service and PsycINFO. The search for unpublished studies included the Open Grey collection, conference proceedings and the Deep Blue Library.

Eligibility criteria

We included qualitative studies that focused on nursing students' perceptions and experiences of incivility from faculty during their clinical education.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers independently appraised the methodological quality and extracted relevant data from each included study. Meta-aggregation was used to synthesise the data.

Results

A total of 3397 studies was returned from the search strategies. Eighteen studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-synthesis. Six synthesised findings were identified, covering features of incivility, manifestations of incivility, contributing factors, impacts on students, coping strategies and suggestions.

Conclusions

The results showed experiences of incivility during clinical education. However, the confidence was low for all synthesised findings. We suggest that nursing students should try to cope positively with incivility. Nurse managers and clinical preceptors should be aware of the prevalence and impact of incivility and implement policies and strategies to reduce incivility towards nursing students. Hospitals and universities should have an immediate response person or system to help nursing students confronting incivility and create an open communication environment.

Keywords: nurse education, incivility, systematic review, meta-synthesis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used the Joanna Briggs Institute meta-aggregation method to synthesise qualitative data, which minimised re-interpretation of original studies.

We performed a comprehensive search strategy to find all relevant studies in nine academic databases and four grey literature databases.

Both published articles and theses were included to provide unbiased results.

We only included studies in English. All included studies were conducted in USA, European countries and Australia. Cultural variation may have accounted for individual responses to incivility.

Introduction

Incivility is defined as a rude and deviant act characterised by low-intensity discourteous behaviour with or without intent to harm, offend and humiliate the target.1 2 For decades, nurse-to-student incivility has been prevalent in clinical settings. The unfortunate idiom ‘nurses eat their young’ has been used for more than 30 years.3 Previous studies showed that nursing students had experiences of being bullied, harassed and unfairly blamed by clinical faculty. The results from a study conducted by Clark and Springer revealed that over 70% of 356 respondents believed that incivility in nursing education was a moderate or serious problem and had increased over the last 5 years.4 A survey conducted in Oman showed over 40% of the respondents experienced different forms of incivility, including being disrespectful, being unprepared for class and cancelling scheduled activities without warning.5 The literature suggests that several key factors contribute to incivility.

Rowland and Srisukho found that gender, class standing, average grade, informal interactions between faculty and students, and academic achievement were the key factors associated with incivility towards students.6 Vink et al indicated that factors contributing to incivility could be categorised into three themes (academic, psychopathological and social factors).7 Other factors identified by previous studies included policies on uncivil behaviours, the political atmosphere and environmental factors.8 9

In the face of high rates of nurse turnover and workforce attrition in nursing, nurse educators and managers have realised that incivility in clinical settings can be contributory because it can harm both individuals and their organisations. Anthony et al and Kinley found that incivility could negatively influence students’ confidence, make them question whether they were completely incompetent as a nurse, and lead to a high level of turnover among new graduate nurses during their first 2 years of employment.10 11 The studies conducted by Seibel and Milesky et al showed that victims of incivility suffered from physical and emotional distress that affected patient care and was related to patient safety.12 13 The report from the Joint Commission showed that uncivil behaviour in the healthcare setting could lead to medical errors, poor clinical outcomes, low patient satisfaction and increased costs of care.14

Nursing faculty incivility in clinical education has also been reported in the literature. Altmiller and Anthony and Yastik conducted focus group interviews to describe the phenomenon of incivility in undergraduate nursing programmes.10 15 Although the qualitative research yielded in-depth information from a small sample of participants, the external validity and transferability of results from a single study were still limited. A variety of aspects of the experience of faculty incivility need to be integrated to produce more robust evidence across multiple qualitative studies. Obtaining a deep understanding of the phenomenon is necessary for the use of mindfulness solutions to inform the practice and transform the culture of the workplace. To obtain a comprehensive picture of this phenomenon, we used the meta-synthesis approach to manage and report findings from multiple qualitative research studies.16

The aim of this study is to synthesise evidence based on the experiences and perceptions of nursing students regarding incivility in clinical education. Specifically, the review addressed the following research questions: (1) What behaviour in the clinical environment did the student consider uncivil? (2) To what extent did these behaviours affect them? (3) What strategies did they use to cope with incivility?

Methods

We used a meta-aggregation approach to conduct a systematic review of qualitative studies following the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative research statement (online supplementary appendix I).17

bmjopen-2018-024383supp001.pdf (129KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria included the following: (1) The participants were current nursing students undergoing clinical education or had already completed their clinical education. (2) The phenomena of interest focused on the perceptions and experiences of incivility from faculty during clinical education. (3) Context: faculty incivility must have occurred in clinical settings or during clinical education. (4) Qualitative studies including but not limited to ethnographies, phenomenologies, narrative studies, grounded theory and case studies; additionally, mixed-method studies with a narrative description of faculty or student voices describing the phenomena under study were also considered. (5) Studies published in English.

Search strategy

We included both published and unpublished papers. A three-step search approach was conducted in this study. First, we searched MEDLINE (via PubMed) to analyse the text words and the index terms that could be used in the comprehensive search. Second, a comprehensive search was conducted across all included databases using keywords and index terms. The databases included CINAHL, PubMed (MEDLINE), ProQuest Central, ProQuest Education Journals, ProQuest XML-Dissertations and Theses, Web of Science, Embase, EBSCO Discovery Service and PsycINFO. The search for unpublished studies included the Open Grey collection, conference proceedings and the Deep Blue Library. Relevant papers published from 1990 until 13 January 2018 were evaluated. The search terms included nurs* AND (student* OR graduate*) AND (incivilit* OR bully* OR workplace violence OR uncivil OR aggression* OR harass*) AND (hospital* OR clinic* OR workplace*). The search strategy for PubMed (MEDLINE) is available in online supplementary appendix II. In the third step, additional studies were searched manually by screening the references of related studies. The search results were imported into Endnote V.X8 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA), which was used to manage the literature.

bmjopen-2018-024383supp002.pdf (111.5KB, pdf)

Critical appraisal

We used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research to assess the methodological quality of the included studies.18 This 10-item JBI critical appraisal tool is designed to assess research quality in different domains, including research methodology and conceptual depth of reporting. Two reviewers appraised the methodological quality of each included study independently (ZZ and WX). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

The JBI standardised form was used to extract qualitative data. The data extraction form included the following domains: study (year), country, design (data collection method), phenomenon of interest, recruitment and participants, and main findings including relevant illustrative quotations. Relevant data were extracted independently by two reviewers (ZZ and WX). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data synthesis

The JBI meta-aggregation method was used to synthesise the data. Meta-aggregation is one approach that can be used to synthesise qualitative evidence based on the primary author’s findings and is a useful method for generating recommendations for action.18 This approach focuses on integration of findings from processed data rather than raw data collected from participants. The overall goal of meta-aggregation is to produce synthesised findings that are highly relevant for practitioners, patients and policy makers.18 Data extraction, comparison and synthesis were conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI-SUMARI).19 The procedures involved four steps. (1) Thorough repeated reading of the paper, with verbatim statements and accompanying quotations extracted from each study by the primary reviewer (WX). Only findings identified as highly correlated with our phenomenon of interest were extracted from each study. To ensure rigour, the second reviewer (ZZ) checked all extractions. (2) Two reviewers (ZZ and WX) independently assigned the credibility level for each research finding. All disagreements were resolved through discussion. If more than one quotation was included for the same finding, we assigned the highest level of credibility (unequivocal >credible > unsupported). (3) Findings rated as unequivocal or credible were aggregated into categories based on similar meanings. Findings rated as unsupported were eliminated from the subsequent analysis. The categories were determined by the primary reviewer (WX) and affirmed by the second reviewer (ZZ). Disagreements were resolved by consensus. (4) Categories with commonality were further integrated into the synthesised findings by the primary reviewers. The synthesised findings and recommendations were examined by all coauthors involved in nursing education.

Confidence in the findings

The synthesised findings were assessed using the JBI approach for rating confidence of synthesised qualitative findings (ConQual) to determine the confidence level.20 The confidence level was rated high, moderate, low or very low based on the dependability and credibility of the included study.

The dependability for each included study was determined through evaluation of five criteria from the JBI critical appraisal for qualitative studies. The criteria evaluated whether the research methods were appropriate for the chosen research design. The dependability of the synthesised finding was based on the dependability of the included study.20

The credibility of each research finding was determined based on the congruity between the study’s interpretation of the findings and the participants’ quotations. The credibility level can be unequivocal (U), credible (C) or unsupported (UN). The credibility of each synthesised finding was based on the credibility level of the individual research findings. If not all research findings included in a synthesised finding were unequivocal (U), then the credibility of the synthesised findings was downgraded.20

Patient and public involvement

No patients or members of the public were involved in the design of this systematic review.

Results

Literature search

The outcomes of the literature search are outlined in figure 1. Initially, a total of 3397 studies was returned from the search strategies. After screening the titles and abstracts, we reduced the number of papers to 53 for full-text evaluation. Subsequently, 18 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-synthesis.15 16 21–36

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the search strategy and results.

Quality assessment

Table 1 summarises the quality assessment of the 18 selected studies. All 18 studies had similar phenomena of interest, methodologies and data analysis methods. Only one study reported the potential beliefs and values of the authors that might have influenced the findings.22 Three studies reported the authors’ roles in the study that might have potentially influenced the interpretation of the findings.22 31 34 One study did not provide representations of the participants and their voices.15 Two studies did not report the ethical approval process.15 28 The disagreement rate between the two reviewers was 6.6%.

Table 1.

Results of quality assessment based on the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 | |

| 1. Altmiller15 (2012) | U | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | U | U | Y |

| 2. Anthony10 (2011) | U | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 3. Birks et al 21 (2017) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 4. Cantey22 (2012) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5. Clark23 (2008) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 6. Courtney-Pratt et al 24 (2017) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 7. Curtis et al 25 (2007) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 8. Del Prato26 (2013) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 9. Hakojarvi et al 27 (2014) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 10. Hoel et al 28 (2007) | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | U | Y | U | Y |

| 11. Jackson et al 29 (2011) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 12. Lash et al 30 (2006) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 13. Martel31 (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 14. Rees et al 32 (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 15. Smith et al 33 (2016) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 16. Thomas34 (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 17. Thomas et al 35 (2015) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| 18. Thomas and Burk 36(2009) | U | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

C1=Congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology.

C2=Congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives.

C3=Congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data.

C4=Congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data.

C5=There is congruence between the research methodology and the interpretation of results.

C6=Locating the researcher culturally or theoretically.

C7=Influence of the researcher on the research.

C8=Representation of participants and their voices.

C9=Ethical approval by an appropriate body.

C10=Relationship of conclusions to analysis, or interpretation of the data.

U, unclear; Y, yes.

Study description

The study characteristics are summarised in table 2. Among the 18 studies, 15 studies were published papers15 16 21 23–30 32 33 35 36 and three were PhD theses.22 31 34 Six studies used individual semistructured or unstructured interviews to collect data,22–24 26 31 34 four studies used focus group interviews,15 16 30 33 four studies used open-ended questionnaires,21 25 27 29 two studies used both individual and group interviews,28 32 and two studies collected data from diaries and stories written by nursing students.35 36 Most of the included studies were published from 2012 to 2017 (n=11).15 21 22 24 26 27 31–35 The studies were conducted in five different countries: USA (n=8),15 16 22 23 26 33 36 37 the UK (n=4),28 31 32 35 Australia (n=4),21 24 25 29 Finland (n=1)27 and Turkey (n=1).30 Six studies reported recruitment across multiple universities/hospitals.15 23 27 28 32 33 Two studies recruited participants through online platforms.21 29 The total number of nursing students included in this systematic review was 1182. Among all of the participants, 348 participants joined an interview and 834 participants completed a questionnaire or diary. The sample sized ranged from 422 to 430 participants.21

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies

| Study (year), country | Design (data collection method) | Phenomenon of interest | Recruitment and participants | Main findings |

| Altmiller15 (2012), USA | Phenomenology (focus group interview) | To describe the phenomenon of incivility in undergraduate nursing programmes. | Four universities in USA; 24 undergraduate junior and senior nursing students |

Nine themes were identified in this study: (1) Unprofessional behaviour. (2) Poor communication techniques. (3) Power gradient. (4) Inequality. (5) Loss of control over one’s world. 6) Stressful clinical environment. (7) Authority failure. (8) Difficult peer behaviours. (9) Students’ views of faculty perceptions. |

| Anthony10 (2011), USA | Descriptive qualitative study (focus group interview) | To describe students’ experiences and perceptions of incivility in clinical education. | One nursing school in USA; 21 nursing students |

The experience of perceived incivility was categorised into three themes: (1) Exclusionary. (2) Hostile or rude. (3) Dismissive. Positive experiences were reported when the students were welcomed by the staff. |

| Birks et al 21 (2017), Australia | Descriptive qualitative study (open-ended questionnaire) | To describe experiences of bullying and harassment among nursing students during clinical education. | An online platform in Australia; 430 nursing students |

Three themes were derived from the analysis: (1) Manifestations of bullying and harassment. (2) The perpetrators. (3) The consequences and impacts. |

| Cantey22 (2012), USA | Narrative inquiry (semistructured interview) | To explore the experience of vertical violence among registered nurses during school nurses’ clinical education. | One generic class in USA; four registered nursing students |

Three themes were gleaned from the data analysis: (1) Rite of passage. (2) Professional identity development. (3) Positive professional role model. |

| Clark 23(2008), USA | Phenomenology (semistructured interview) | To describe nursing students’ experiences of uncivil encounters with nursing faculty. | Four nursing schools in USA; seven current and former nursing students |

Three major themes were identified regarding incivility conducted by faculty: (1) Behaving in demeaning and belittling ways. (2) Treating students unfairly and subjectively. (3) Pressuring students to conform to unreasonable faculty demands. Three major themes were identified regarding students’ emotional responses: (1) Feeling traumatised. (2) Feeling powerless and helpless. (3) Feeling angry and upset. |

| Courtney-Pratt et al 24 (2017), Australia | Mixed methods (semistructured interviews) | To explore nursing students' experiences with bullying in clinical and academic settings. | One Australian university; 29 first-year, second-year and third-year undergraduate nursing students |

Four themes were derived from the analysis: (1) Manifestations of bullying in clinical and academic settings. (2) Impact of experiences on students and the strategies students used to ‘make sense of’ and address bullying. (3) Recommendations from students on how to prepare for bullying. (4) Recommendations on how to manage bullying. |

| Curtis et al 25 (2007), Australia | Descriptive qualitative study (open-ended questionnaire) | To investigate nursing students' experiences with horizontal violence in the nursing workplace in Australia. | One university in Australia; 152 second-year and third-year nursing students |

Five major themes were identified: (1) Humiliation and lack of respect. (2) Powerlessness and becoming invisible. (3) Hierarchical nature of horizontal violence. (4) Coping strategies. (5) Future employment choices. |

| Del Prato26 (2013), USA | Phenomenology (in-depth interviews) | To understand students' experiences with faculty incivility in associate degree nursing education. | One university in USA; 13 nursing students from three associate degree nursing education programmes |

Faculty incivility was categorised into four themes: (1) Demeaning experiences. (2) Subjective evaluation. (3) Rigid expectations. (4) Targeting and weeding out practices. |

| Hakojarvi et al 27 (2014), Finland | Descriptive study (an electronic semistructured questionnaire) | To describe healthcare students' (including nursing students) personal experiences with bullying by staff or clinical instructors in clinical settings. | Two universities in Finland; 41 healthcare students |

1) Students experienced both verbal and non-verbal bullying during clinical training. 2) Bullying influenced the students’ motivation and professional engagement. 3) Some students thought that sharing the experience with their teacher and instructors was useless. However, those students who shared the bullying experience received emotional support and information. |

| Hoel et al 28 (2007), the UK | Not specified (focus group interview and one-on-one interview) | To explore nursing students’ experiences and perceptions of bullying in a clinical setting. | Recruited from universities and an advertisement in the UK; 48 nursing students |

1) Students felt exploited, ignored and unwelcome. 2) Bullying experiences had strong effects on the institutionalising and unwelcoming culture in the clinical setting. 3) Students’ coping mechanisms contributed to reproducing negative behaviours towards them. |

| Jackson et al 29 (2011), Australia | Not specified (open-ended questionnaire) | To explore undergraduate students' experiences of negative behaviours in clinical settings. | An online website in Australia; 105 nursing students from a large Australian university |

Three themes were categorised: (1) Confronted by contradiction: students as ’other'. (2) Organisational aggression as a legitimating device. (3) Resisting ‘othering’: securing a legitimate identity as a student. |

| Lash et al 30 (2006), Turkey | Phenomenology (focus group interview) | To describe nursing and midwifery students’ experiences with perceived verbal abuse in clinical settings in Turkey. | One university in Turkey; 73 nursing and midwifery students |

Four categories were derived from the interviews: (1) Experiences of verbal abuse. (2) Perceptions of the effects of verbal abuse. (3) Methods of coping with verbal abuse. (4) Recommendations to prevent and effectively respond to the verbal abuse. |

| Martel31 (2015), the UK | Phenomenology (semistructured interviews) | To describe the experiences of nursing students with nursing staff incivility. | One university in the UK; seven bachelor degree nursing students |

Uncivil behaviours were grouped into three themes: (1) Lack of receptiveness. (2) Belittling. (3) Failing to recognise the assistance of students. Consequences of uncivil behaviours included emotional hurt, loss of confidence, discouragement, fear, demotivation and unhappiness |

| Rees et al 32 (2015), the UK | Not specified (individual and group interviews) | To explore dental, nursing, pharmacy and physiotherapy students’ experiences with workplace abuse. | Three universities in the UK; 69 healthcare students (n=13 nursing students) |

(1) Covert abuse was the most reported type of abuse in the narratives. (2) Individual, relational, work and organisational factors contributed to abuse; the perpetrator was the most important factor. (3) Most participants acted in the face of their abuse. (4) The perpetrator-recipient relationship was the main contributory factor. |

| Smith et al 33 (2016), USA | Descriptive qualitative study (focus group interview) | To explore what types of bullying behaviours were encountered by nursing students in the clinical placement and how these encounters impacted them. | Four colleges in USA; 56 undergraduate nursing students |

Four categories were identified: (1) Bullying behaviours. (2) Rationale for bullying. (3) Response to bullying. (4) Recommendations to address bullying. |

| Thomas34 (2015), USA | Phenomenology (semistructured interviews) | To understand nursing students’ experience with incivility in a clinical education setting. | One university in USA; 12 junior and senior nursing students in a baccalaureate nursing programme |

Nursing students felt unprepared to effectively respond when encountering incivility and experienced emotional and behavioural harm from the encounters. |

| Thomas et al 35 (2015), the UK | The classic grounded theory (diary) | To explore the impacts of the first clinical placement on the professional socialisation of adult undergraduate student nurses in the UK. | Twenty-six undergraduate adult student nurses in the UK | Incivility is comprised of three stages: (1) Stage of dislocation (disillusionment with role, needing benevolence and being altruistic). (2) Stage of status negotiation (significant others, seeking recompense and brokering for learning). (3) Stage of status relocation (being benevolent, maintaining values and recanting status). |

| Thomas and Burk36 (2009), USA | Descriptive study (written stories) | To explore the experiences of injustice perpetrated by staff RNs during nursing students' clinical placement. | One university in USA; 221 junior nursing students |

Four levels of injustice were described: (1) ‘We were unwanted and ignored’. 2) ‘Our assessments were distrusted and disbelieved’. (3) ‘We were unfairly blamed’. (4) ‘I was publicly humiliated’. |

Review finding

Eighty findings were retrieved from 18 articles. Six synthesised findings were identified. Of these findings, 70 were rated as unequivocal and 10 as credible. An overview of these synthesised findings is summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Synthesised findings

| Findings | Categories | Synthesised findings |

| Diverse, overt and covert, verbal and non-verbal (U) | Feature/nature of incivility | (1) Different types of incivility can be experienced by nursing students. Some types are noticeable, whereas others can be more subtle and are difficult to prove. Most nursing students are unprepared for incivility from multiple perpetrators. |

| Unavoidable, unprepared, pervasive and recurring (U) | ||

| Ongoing and endless, continued in professional lives (U) | ||

| Multiple perpetrators, clinical instructors, other nursing staff, physicians, healthcare assistants and ward cleaners (U) | ||

| Difficult to prove (U) | ||

| Hierarchical (C) | ||

| Failed to provide learning opportunities or guidance (U) | Lack of professionalism | (2) Faculty incivility in the clinical education context towards nursing students manifests as a lack of professionalism in the workplace, being disrespectful and unfair towards nursing students, and making nursing students feel unwanted and ignored in the workplace. Worse, some manifestations, including physical abuse and sexual harassment, violate the law. |

| Rigid expectations for students’ abilities (U) | ||

| Excessive use of students for legwork or their own gains (U) | ||

| Arbitrary changes in syllabi, assignments and schedules (U) | ||

| Being questioned inadequately (C) | ||

| Constant criticism and negative feedback (U) | ||

| Not protecting students’ safety (U) | ||

| Belittlement (U) | Disrespect | |

| Condescending (U) | ||

| Being intimidated (U) | ||

| Personality criticism (C) | ||

| Humiliation in front of staff and patients (U) | ||

| Talking about students behind their backs (U) | ||

| Being called derogatory names (U) | ||

| Being shouted at (U) | ||

| Hostile body language (eye rolling and avoiding eye contact) (U) | ||

| Feeling like a nuisance (U) | Unwanted and ignored | |

| Not being involved in nursing activities (U) | ||

| Refusal to answer, help or support (U) | ||

| Not being permitted to use staff room (U) | ||

| Favouritism (U) | Inequality | |

| Being targeted or retaliation (U) | ||

| Racial/ethnic bias (U) | ||

| Gender bias (U) | ||

| Appearance bias (U) | ||

| Subjective evaluation (U) | ||

| Physical abuse (U) | Other manifestations that violate the law | |

| Sexual harassment (U) | ||

| Helplessness/hopelessness/powerlessness (U) | Psychological symptoms | (3) Faculty incivility in the clinical education context has a huge physical and emotional impact on nursing students and influences the professional formation process. |

| Loss of self-esteem, worth and confidence (U) | ||

| Stress, depression, distress, fear, anger, upset and anxiety (U) | ||

| Suicidal or self-harm (C) | ||

| Sleep disorders, fatigue, sweating, tearfulness, nausea, vomiting, headaches, chest pain, palpitations, cardiac and abdominal symptoms, and overeating or appetite loss (U) | Physical symptoms | |

| Deleterious consequences for patients (C) | Professional formation | |

| Doubting profession choice and having the desire to quit nursing (U) | ||

| Loss of motivation, productivity and performance (U) | ||

| Tolerated and reticent to report (U) | Negative coping | (4) Facing faculty incivility in the clinical context, nursing students can develop either negative or positive coping strategies to accept the harsh realities of life or fight incivility. |

| Becoming invisible (U) | ||

| Accept as a part of student life (U) | ||

| Leave nursing programme (U) | ||

| Standing up to report (U) | Positive coping | |

| Improving communication with staff (U) | ||

| Sharing with families and friends (U) | ||

| Seeking support from nice nursing faculty (U) | ||

| Seeking advice from trusted university staff (U) | ||

| Sharing in end-of-semester evaluations (U) | ||

| Trying to understand staff’s viewpoint (U) | ||

| Developing self-resilience (C) | ||

| Maintaining self-values and restoring confidence (U) | ||

| Being benevolent and not perpetuating incivility (U) | ||

| Conflicts among staff (U) | Staff-related factors | (5) Students’ individual factors, staff factors and clinical culture factors place nursing students at risk for incivility. These factors work individually or collectively. |

| Workplace stressors and overload (U) | ||

| Personal life stressor (U) | ||

| Previous bad encounters with students (U) | ||

| Limited availability of instructor (U) | ||

| Limited competency (U) | ||

| Characteristics and personalities (U) | ||

| Misperceptions about university education (U) | ||

| Generation gap (C) | ||

| Showing less respect (U) | Student-related factors | |

| Limited power (C) | ||

| Youth, gender and inexperience (U) | ||

| Characteristics and personalities (U) | ||

| Rite of passage/vicious cycle (U) | Culture-related factors | |

| The culture of ‘students not welcome’ (U) | ||

| Educate and prepare students’ responses to incivility (U) | Suggestions to university | (6) Both the university and hospital can consistently respond to faculty incivility in clinical education towards nursing students. Building an anti-incivility environment requires that the university and hospital work together. |

| Immediate response person or system (U) | ||

| Faculty follow-up and monitoring (U) | ||

| Peer support and opportunities (U) | ||

| Qualifications of preceptors and continuous evaluation (U) | Suggestions to hospital | |

| Having perceived authority of instructors (C) | ||

| Clarifying the role of nursing students (U) | ||

| Positive professional role model (C) |

Synthesised finding 1

Different types of incivility can be experienced by nursing students. Some types are noticeable, whereas others can be more subtle and are difficult to prove. Most nursing students are unprepared for incivility from multiple perpetrators.

This synthesised finding originated from six findings and was grouped into one category. Many of the studies describe the features of the incivility. The nursing students perceived diverse incivilities in the clinical workplace. The forms of incivility could be either overt or covert, and verbal or non-verbal.21 24 Many nursing students believed that incivility in the clinical workplace was pervasive and recurring and that experiencing incivility during clinical education was unavoidable.21 24 33 One nursing student indicated that incivility was a ‘rite of passage’.21

It is a serious issue, more of the bullying occurs from registered nurses, a profession where we are meant to care for one another. They are eating their young and wonder why people want to quit nursing. They forget they were just like us once. 21

Because the idea of equality between nursing students and clinical staff did not seem viable, the incivility was apparently ongoing and not a one-time occurrence.25 34 In this hierarchical system, nursing students believed that to succeed they had to accept their role as defined by those with power and authority.15 25 34 They described perceiving incivility from multiple perpetrators, including clinical instructors, other nursing staff, physicians, healthcare assistants and ward cleaners.21 27–30 34 However, the students felt that proving they were being bullied or maltreated was difficult.27

Synthesised finding 2

Faculty incivility in the clinical education context towards nursing students manifests as a lack of professionalism in the workplace, being disrespectful and unfair towards nursing students, and making nursing students feel unwanted and ignored in the workplace. Worse, some manifestations, including physical abuse and sexual harassment, violate the law.

This synthesised finding originated from 28 findings and was grouped into five categories. The acts of incivility in clinical education can be categorised into lack of professionalism, being disrespectful, feeling unwanted and ignored, inequality, physical abuse, and sexual harassment.

Nursing students noted a range of manifestations as a lack of professionalism from medical staff, including failing to provide learning opportunities or guidance,30 31 having rigid expectations for students’ abilities,21 23 26 32 36 excessive use of students for legwork or their own gains,30–32 36 arbitrary changes in syllabi, assignments and schedules,23 questioning students inadequately,34 giving constant criticism and negative feedback,26 31 34 and not protecting the students’ safety.31

A nurse said, ‘You are wasting your time with care plans. We used to do them, but they do not work.’ After hearing this, I lost confidence in my education. 30

Fourteen studies noted disrespectful behaviours from the medical staff. Characteristics exemplifying disrespectful behaviour included belittlement,15 23 26 28 29 34 36 being condescending,23 33 intimidation,26 32 33 criticism of personality,21 36 humiliation in front of staff and patients,21 22 25–27 32 36 talking about students behind their backs,21 calling students derogatory names,21 31–33 shouting at students,27 32 and having hostile body language (eg, eye rolling and avoiding eye contact).21 35 36

… and then in the end… she just got a bit angry with me sort of in front of the patient and said some things like (coughs) I didn’t quite think were acceptable to say in front of the patients… rather than helping me she just got angry with me. 32

Twelve studies noted unwanted or ignored behaviours bestowed by medical staff towards nursing students. The forms included making the nursing student feel like a nuisance,10 24 29 32–36 not letting the students be involved in nursing activities,21 31 refusal to answer, help or support,15 21 29 31 32 34 36 and not permitting the student to use the staff room.21 25

How wrong I was. I have never felt so unwanted in my life. The nursing staffs made me feel like a complete nuisance…I don’t think she even made eye contact with me… She seemed annoyed by my presence…. 36

Inequality for all students was identified as another form of incivility. Bias was commonly based on gender, race, appearance and behaviours.15 21 23 26 Some faculty favoured male nursing students and younger nursing students and were more positive in their communications with them.15 23 The students with unusual behaviours had more challenges.24 29 30 Some nursing students admitted they feared that they were being targeted and avoided any interaction at all with certain instructors.15 26

On my clinical placement, I was immediately judged by one staff member who continuously embarrassed me… They took an instant dislike to me (because of) my appearance and made comments stating I was a princess and spoilt. They treated other students and team members with… respect, however I did not receive any of this. 31

Other forms of incivility include physical threats and sexual harassment. Two studies provided examples of nursing students being stalked and experiencing inappropriate touching by staff.21 33 Worryingly, some nursing students experienced different forms of physical threats, such as a nurse instructor throwing items (patient file folders, intravenous fluid bags and a key) at the students.21 24 32 33

Synthesised finding 3

Faculty incivility in the clinical education context has a huge physical and emotional impact on nursing students and influences the professional formation process.

This synthesised finding originated from eight findings and was grouped into three categories. Studies described the impact of perceiving incivility from faculty, including having negative emotions and physical symptoms and questioning the nursing profession. Feelings of helplessness, hopelessness and powerlessness were the most common emotional responses noted by the participants.15 23 25 27 30 Other negative emotions included loss of self-esteem, worth and confidence, stress, depression, fear, anger, upset, and anxiety.21–24 26 27 30 31 33 34 Some students reported that they had a serious suicidal tendency and wanted to conduct self-injury to escape from clinical education.21

I realised that no matter how hard we worked in our clinical group, that it was the instructor’s way or no way. It wasn’t our work we were being evaluated on; it was our ability to please her. If we didn’t look good, she didn’t look good. If we embarrassed her, she would squash us, she would fail us. We felt helpless. 23

The consequences of incivility included suffering from physical symptoms. These reactions included sleep disorders, fatigue, sweating, nausea, vomiting, headaches, chest pain, nervousness, palpitations, cardiac and abdominal symptoms, and overeating or appetite loss.21 23 27 30 31 34 In addition, incivility also caused issues with loss of motivation, productivity and performance.27 30 33 34 The students' professional engagement was negatively affected by incivility. In nine studies, nursing students expressed incivility as criticism of clinical education and the nursing profession and doubt towards their career choice.10 21 22 24 26 27 30 31 33 34

I am making it my duty as a registered nurse to never forget how it felt as a student that was bullied on placement. 21

Bullying has totally eroded the credibility of the profession in my eyes. 27

Synthesised finding 4

Facing faculty incivility in the clinical context, nursing students can develop either negative or positive coping strategies to accept the harsh realities of life or fight incivility.

This synthesised finding originated from 15 findings and was grouped into two categories. Studies noted that nursing students developed different responses to incivility when they perceived uncivil treatment through their education. The categories included negative coping and positive coping. Nine studies described negative coping strategies. Students often felt powerless to deal with incivility, and the most common response was to remove themselves from the situation.25 33 Students were reluctant to report the incidences of perceiving incivility and felt that their actions were unlikely to lead to change.10 15 21 24 25 30 36 They accepted the harsh clinical education as a part of student life.30 However, some nursing students chose to change their major and left the nursing programme.23

We have to get used to verbal abuse incidents like this. Ultimately, we have to accept the clinical reality. The most important goal is to graduate. My mother is my best counsel. She keeps saying, ‘Be patient! It will come to an end'. 30

Eleven studies noted that nursing students confronted incivility by using positive coping strategies. Positive strategies including standing up to report the incivility they perceived to a high level,10 21 23 29 30 34 improving communication with the medical staff,10 25 30 34 35 sharing the story with their families and friends,23 24 27 30 35 seeking support from other friendly nurse faculty and trusted university staff,23 24 sharing the experience in end-of-semester evaluations,34 trying to understand the staff’s viewpoint,35 developing self-resilience,21 25 maintaining self-values and restoring confidence.22 35 Many nursing students who had perceived incivility once noted that they would not be disrespectful to students in the future.21 25

Spent the afternoon shadowing a second-year student. She was really helpful and friendly. I found it reassuring that she had experienced the same anxieties and fears. 35

I am making it my duty as a registered nurse to never forget how it felt as a student that was bullied on placement. I was shocked that nurses − (supposedly) such a caring profession − could be so ruthless towards students. I think bullying in nursing really needs to stop. 21

Synthesised finding 5

Students’ individual factors, staff factors and clinical culture factors place nursing students at risk for incivility. These factors work individually or collectively.

This synthesised finding originated from 15 findings and was grouped into three categories. Although there is absolutely no excuse for medical staff to harass and humiliate nursing students, most incivilities had underlying reasons that led to this behaviour. The possible reasons were categorised into staff-related reasons, student-related reasons and culture. Staff-related factors were identified as the main trigger for incivility, including conflicts among staff,28 work overload and workplace stressors,15 33–35 personal life stressors,34 previous encounters with students,34 limited availability of instructor,15 limited competency,15 individuals’ characteristics and personalities,34 misperceptions about university education,30 34 and a generation gap.31 33

It is like a lot of the time the nurses are overwhelmed. They have six or seven patients instead of the four that they should have and.they convey their stress on to people. They put it onto others—and it turns into bullying, but it’s really you know ‘I feel overworked’ or ‘I’m too told to be in this position’ or ‘I can’t lift like I (used) to’. 33

According to student-related factors, incivility is a mutual conflict that depends on how well nursing students respect their clinical instructor. Nursing students showing less respect for their instructors was the common trigger for incivility.20 Notably, two studies noted that students’ youth, gender, personalities and inexperience in the work environment increased their risk of being subjected to incivility.30 34 However, nursing students are a vulnerable population in the clinical environment, which makes them easily targeted and crushed.21

Clinical culture is another factor that contributes to incivility towards nursing students. In particular, the included studies showed that bullying was a rite of passage of culture transition from school to the new hierarchical environment.21 22 24 28 33 One study showed that a ‘student not welcome’ culture in the clinical setting could also create incivilities.33

Some nurses are very nice to students and very helpful and others you get the vibe you know they don’t want you there. 33

Synthesised finding 6

Both the university and hospital can consistently respond to faculty incivility in clinical education towards nursing students. Building an anti-incivility environment requires that the university and hospital work together.

This synthesised finding originated from eight findings and was grouped into two categories. The last synthesised finding describes suggestions from nursing students for universities and hospitals. The suggestions for universities can be categorised into four sectors;24 33 educating and preparing student responses to incivility; having an immediate response person or system; having faculty to follow-up and continue monitoring; and having peer support and other opportunities.

The university should have an immediate response person or system to ensure immediate support. We need a phone number or email for help and advice straight away, like you can call and say this has happened. 24

Suggestions to hospitals can be categorised into four factors;22 30 33 qualifying preceptors and performing continuous evaluations; having perceived authority as instructors; clarifying the roles of students; and establishing a positive professional role model.

Those nurses are acting as teachers and some people weren’t meant to be teachers. They may be good nurses but they’re not good teachers, and they need to think about that more in terms of who they’re assigning and make the compensation for it so they want to do it, the ones who are good at it want to do it. It should be a regular thing where they’re evaluated on it. 33

ConQual summary of synthesised findings

The ConQual Scores and the summary of the synthesised findings are provided in table 4. The confidence was low for six synthesised findings, where were downgraded one level due to dependability limitation issues. A mix of unequivocal and credible findings was another reason to downgrade the credibility of all of the included studies.

Table 4.

ConQual summary of findings

| Synthesised findings | Type of research | Dependability | Credibility | ConQual Score |

| (1) Different types of incivility can be experienced by nursing students. Some types are noticeable, whereas others can be more subtle and are difficult to prove. Most nursing students are unprepared for incivility from multiple perpetrators. | Qualitative | Downgrade one level | Downgrade one level | Low |

| (2) Faculty incivility in the clinical education context towards nursing students manifests as a lack of professionalism in the workplace, being disrespectful and unfair towards | Qualitative | Downgrade one level | Downgrade one level | Low |

| (3) Faculty incivility in the clinical education context has a huge physical and emotional impact on nursing students and influences the professional formation process. | Qualitative | Downgrade one level | Downgrade one level | Low |

| (4) Facing faculty incivility in the clinical context, nursing students can develop either negative or positive coping strategies to accept the harsh realities of life or fight incivility. | Qualitative | Downgrade one level | Downgrade one level | Low |

| (5) Students’ individual factors, staff factors and clinical culture factors place nursing students at risk for incivility. These factors work individually or collectively. | Qualitative | Downgrade one level | Downgrade one level | Low |

| (6) Both the university and hospital can consistently respond to faculty incivility in clinical education towards nursing students. Building an anti-incivility environment requires that the university and hospital work together. | Qualitative | Downgrade one level | Downgrade one level | Low |

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-synthesis provided a comprehensive picture of nursing students’ experiences with faculty incivility in the available literature. Based on the exhaustive search strategies, 18 studies were included. Six synthesised findings were identified, covering features of incivility, manifestations of incivility, contributing factors, impacts on students, coping strategies and suggestions.

The meta-synthesis revealed that in addition to disrespect, feelings of being unwanted and ignored, inequality, and lack of professionalism were identified as important displays of workplace incivility. This finding added to our knowledge that nursing students regarded instructors who acted without professionalism as uncivil, which was different from faculty-to-faculty incivility.38 In the clinical education setting, nursing students still expect preceptors to be role models and demonstrate positive and constructive manners.39 40 Even working with medical teams, most nursing students are subjected to a structured academic setting during the transition from a student to a nurse.41 42 Therefore, nursing student orientation uses the same evaluation standard to measure the behaviours of both clinical preceptors and academic faculty. This result indicates that a qualification assessment and training are essential for clinical nurse preceptors.

Our study also showed that the impact of incivility was very far-reaching. Students who perceived such incivility at work would bring home the negative emotions and would lose motivation in the next few days and doubt their profession choice in the future. Clinical education is the first time that nursing students transit from learning in classrooms to studying in real care environments. Previous studies showed that clinical education was the crucial period when nursing students cultivated professionalism.10 11 The experience perceived by the students is highly associated with job satisfaction and turnover intention.43 Therefore, incivility is a barrier to professional formation and will worsen the shortage of nurses. Incivility in nursing clinical education programmes is particularly crucial during a time of critical nursing shortages worldwide. Universities and hospitals have an ethical mandate to ensure that nursing students and preceptors are practising in areas that do not negatively influence student health and help students form professionalism.44

Different from previous discoveries, our study showed that many nursing students adopted positive strategies to cope with incivility. Previous studies noted that students tended to use avoidant strategies when facing uncivil behaviours.15 26 The use of negative coping strategies may contribute to increased emotional burdens, being the target of incivility and holding a grudge against the victimiser.37 Nevertheless, in recent years, a series of antibullying campaigns have popped up everywhere in response to the situation of uncivil behaviours in schools. Ending bullying has become a trend among students.45 Some studies have argued students should come to a resolution between themselves and the person exhibiting incivility.46 47 However, unlike facing a bully, dealing directly with the uncivil person may not be a good option. Incivility manifests as a rude or disrespectful action that is difficult to use to invoke adverse management actions at the organisational level. In our study, seeking help from a trusted person and organisation was the most common strategy used by nursing students. Using indirect confrontation coping strategies can elicit positive results for students, such as accommodating negative emotions, which is beneficial for building good interpersonal work relationships.23 24 48 Additionally, these strategies can protect victims in the hierarchical system.30 34 Therefore, hospitals or universities should have an immediate response person or system to help nursing students confronting incivility and to follow-up and monitor the development.

We found that work overload and job stress were important factors contributing to incivility. This result is similar to those of previous studies showing that work overload may increase an employee’s tendency to display uncivil behaviours and provide them with no time for niceties.49 A significant relationship exists among workplace incivility, job stress and turnover intention.50 The consequences of overload and unmanaged stress are incivility. Stress stemming from incivility can also silently kill productivity of staff/students. The vicious cycle of ‘overload work-work stress-incivility’ should be broken. Self-monitoring is an important process during which medical staff should detect, reflect on and assess their own behaviour. In particular, preceptors need to know the emotional triggers and how to curb negative responses. Nurse leaders can provide stress-reducing interventions to lead the organisational cultural to develop a more open communication environment and have less incidences of workplace incivility.

Another issue needs to be considered when interpreting our findings. The levels of confidence across six synthesised findings were downgraded due to dependability issues and a mix of unequivocal and credible findings. Among the 18 included studies, the majority did not report the authors’ influences (eg, roles, beliefs and value) on the studies, which influenced the dependability of all synthesised findings. We recommend that future studies strengthen the methodological quality of qualitative studies and add credibility to the research findings.

The strength of this study is that we performed a comprehensive search strategy to find all relevant studies in nine academic and four grey literature databases. Both journal articles and theses were included to provide unbiased results. Another strength is that we used the JBI meta-aggregation method to synthesise qualitative data, which avoided re-interpretation of the original studies. Finally, to the best of our knowledge, no qualitative systematic review has examined this topic.

Limitations

Our study also has limitations. First, similar to all meta-syntheses, the findings are limited by the study quality and the interpretations of the original researchers. Additionally, we only included studies in English. All included studies were conducted in USA, European countries and Australia. Cultural variation may have resulted in variation in individual responses to incivility. Therefore, the findings can only be generalised to other contexts with a similar culture.

Conclusions

This study synthesised qualitative evidence on the experiences and perceptions of incivility during clinical education of nursing students and evaluated the influence of incivility on student nurses. The findings showed that the experience of incivility in clinical education was common and had negative impacts on nursing students and the nursing profession. We suggest that nursing students should try to cope with incivility positively. Nurse managers and clinical preceptors should be aware of the prevalence and impact of incivility and implement policies and strategies to reduce incivility towards nursing students. Hospitals and universities should have an immediate response person or system to help nursing students confronting incivility and create an open communication environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the visiting scholars in the NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing for their invaluable comments on this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study design: WX; data collection and appraisal; data analysis: manuscript writing: ZZ, WX; study supervision: YH; critical revisions for important intellectual content: LL, YH, MG. All authors revised and accepted the final draft.

Funding: This work was supported by the Fudan Nursing Foundation (FNF201520).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. D’Ambra AM, Andrews DR. Incivility, retention and new graduate nurses: an integrated review of the literature. J Nurs Manag 2014;22:735–42. 10.1111/jonm.12060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spence Laschinger HK, Leiter M, Day A, et al. . Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. J Nurs Manag 2009;17:302–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.00999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gillespie GL, Grubb PL, Brown K, et al. . "Nurses eat their young": a novel bullying educational program for student nurses. J Nurs Educ Pract 2017;7:11 10.5430/jnep.v7n7P11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clark CM, Springer PJ. Incivility in nursing education: a descriptive study of definitions and prevalence. J Nurs Educ 2007;46:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Muliira JK, Natarajan J, van der Colff J. Nursing faculty academic incivility: perceptions of nursing students and faculty. BMC Med Educ 2017;17:253 10.1186/s12909-017-1096-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rowland ML, Srisukho K. Dental students' and faculty members' perceptions of incivility in the classroom. J Dent Educ 2009;73:119–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vink H, Adejumo O. Factors contributing to incivility amongst students at a South African nursing school. Curationis 2015;38:1–6. 10.4102/curationis.v38i1.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ibrahim SA, Qalawa SA. Factors affecting nursing students' incivility: As perceived by students and faculty staff. Nurse Educ Today 2016;36:118–23. 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Swinney L, Elder B, Seaton P. Lost in a crowd: Anonymity and incivility in the accounting classroom. The Accounting Educators' Journal 2010;20. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anthony M, Yastik J. Nursing students' experiences with incivility in clinical education. J Nurs Educ 2011;50:140–4. 10.3928/01484834-20110131-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kinley DJ. Student nurse experiences with staff nurse incivility in clinical settings: University of Alaska Anchorage, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seibel M. For us or against us? Perceptions of faculty bullying of students during undergraduate nursing education clinical experiences. Nurse Educ Pract 2014;14:271–4. 10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Milesky JL, Baptiste D-L, Foronda C, et al. . Promoting a culture of civility in nursing education and practice. J Nurs Educ Pract 2015;5:90 10.5430/jnep.v5n8p90 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alert SE. Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel Event Alert 2008;9:40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Altmiller G. Student perceptions of incivility in nursing education: implications for educators. Nurs Educ Perspect 2012;33:15–20. 10.5480/1536-5026-33.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pearson A. Balancing the evidence: incorporating the synthesis of qualitative data into systematic reviews. JBI Reports 2004;2:45–64. 10.1111/j.1479-6988.2004.00008.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lockwood C, Porrit K, Munn Z, et al. . Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence : Aromataris E, Munn Z, Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Munn Z, Lockwood C, Moola S. The development and use of evidence summaries for point of care information systems: a streamlined rapid review approach. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2015;12:131–8. 10.1111/wvn.12094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joanna Briggs Institute. Summary of findings tables for Joanna Briggs Institute Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2016. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Summary_of_Findings_Tables_for_Joanna_Briggs_Institute_Systematic_Reviews-V3.pdf.

- 21. Birks M, Budden LM, Biedermann N, et al. . A ‘rite of passage?’: Bullying experiences of nursing students in Australia. Collegian 2018;25:45–50. 10.1016/j.colegn.2017.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cantey SW. Vertical violence and the student nurse: Is this toxic for professional identity development? University of Southern Mississippi, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clark C. Student voices on faculty incivility in nursing education. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Courtney-Pratt H. I was yelled at, intimidated and treated unfairly”: Nursing students’ experiences of being bullied in clinical and academic settings, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Curtis J, Bowen I, Reid A. You have no credibility: nursing students' experiences of horizontal violence. Nurse Educ Pract 2007;7:156–63. 10.1016/j.nepr.2006.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Del Prato D. Students' voices: the lived experience of faculty incivility as a barrier to professional formation in associate degree nursing education. Nurse Educ Today 2013;33:286–90. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hakojärvi HR, Salminen L, Suhonen R. Health care students' personal experiences and coping with bullying in clinical training. Nurse Educ Today 2014;34:138–44. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoel H, Giga SI, Davidson MJ. Expectations and realities of student nurses' experiences of negative behaviour and bullying in clinical placement and the influences of socialization processes. Health Serv Manage Res 2007;20:270–8. 10.1258/095148407782219049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jackson D, Hutchinson M, Everett B, et al. . Struggling for legitimacy: nursing students' stories of organisational aggression, resilience and resistance. Nurs Inq 2011;18:102–10. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lash AA, Kulakaç O, Buldukoglu K, et al. . Verbal abuse of nursing and midwifery students in clinical settings in Turkey. J Nurs Educ 2006;45:396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martel ME. Bachelor’s degree nursing students' lived experiences of nursing staff’s incivility: A phenomenological study: Capella University, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rees CE, Monrouxe LV, Ternan E, et al. . Workplace abuse narratives from dentistry, nursing, pharmacy and physiotherapy students: a multi-school qualitative study. Eur J Dent Educ 2015;19:95–106. 10.1111/eje.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith CR, Gillespie GL, Brown KC, et al. . Seeing students squirm: nursing students' experiences of bullying behaviors during clinical rotations. J Nurs Educ 2016;55:505–13. 10.3928/01484834-20160816-04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thomas CA. Nursing student encounters with incivility during education in a clinical setting: Capella University, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thomas J, Jinks A, Jack B. Finessing incivility: The professional socialisation experiences of student nurses' first clinical placement, a grounded theory. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35:e4–e9. 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thomas SP, Burk R. Junior nursing students' experiences of vertical violence during clinical rotations. Nurs Outlook 2009;57:226–31. 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Van den Brande W, Baillien E, De Witte H, et al. . The role of work stressors, coping strategies and coping resources in the process of workplace bullying: A systematic review and development of a comprehensive model. Aggress Violent Behav 2016;29:61–71. 10.1016/j.avb.2016.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peters AB. Faculty to faculty incivility: experiences of novice nurse faculty in academia. J Prof Nurs 2014;30:213–27. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sabog RF, Caranto LC, David JJ. Effective characteristics of a clinical instructor as perceived by bsu student nurses. Int J Nurs Sci 2015;5:5–19. 10.5923/j.nursing.20150501.02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gustafsson M, Kullén Engström A, Ohlsson U, et al. . Nurse teacher models in clinical education from the perspective of student nurses--A mixed method study. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35:1289–94. 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nash R, Lemcke P, Sacre S. Enhancing transition: an enhanced model of clinical placement for final year nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2009;29:48–56. 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Neishabouri M, Ahmadi F, Kazemnejad A. Iranian nursing students' perspectives on transition to professional identity: a qualitative study. Int Nurs Rev 2017;64:428–36. 10.1111/inr.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blackstock S, Harlos K, Macleod ML, et al. . The impact of organisational factors on horizontal bullying and turnover intentions in the nursing workplace. J Nurs Manag 2015;23:1106–14. 10.1111/jonm.12260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rees CE, Monrouxe LV, McDonald LA. ’My mentor kicked a dying woman’s bed…' analysing UK nursing students' ’most memorable' professionalism dilemmas. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:169–80. 10.1111/jan.12457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Herkama S, Salmivalli C. 10. Making large-scale, sustainable change: experiences with the KiVa anti-bullying pro-gramme Ending the torment: tackling bullying from the schoolyard to cyberspace . 2016;75. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Luparell S, Conner JR. Managing student incivility and misconduct in the learning environment. Teaching in Nursing-E-Book: A Guide for Faculty 2015;230. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gillespie GL, Brown K, Grubb P, et al. . Qualitative evaluation of a role play bullying simulation. J Nurs Educ Pract 2015;5:73 10.5430/jnep.v5n6p73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Condon BB. Incivility as bullying in nursing education. Nurs Sci Q 2015;28:21–6. 10.1177/0894318414558617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fontaine DK, Haizlip J, Lavandero R. No time to be nice in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care 2018;27:153–6. 10.4037/ajcc2018401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oyeleye O, Hanson P, O’Connor N, et al. . Relationship of workplace incivility, stress, and burnout on nurses' turnover intentions and psychological empowerment. J Nurs Adm 2013;43:536–42. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182a3e8c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024383supp001.pdf (129KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024383supp002.pdf (111.5KB, pdf)