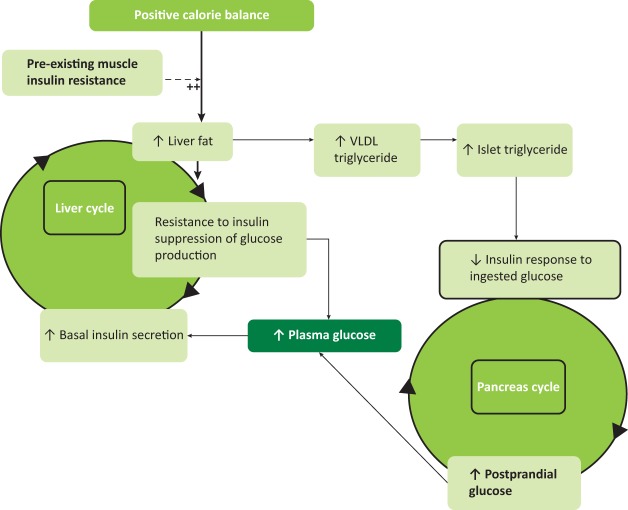

Fig 1.

The twin cycle hypothesis: during long-term intake of more calories than are expended each day, excess carbohydrate must undergo de novo lipogenesis, which particularly promotes fat accumulation in the liver. As insulin stimulates de novo lipogenesis, people with insulin resistance (determined by family or lifestyle factors) will accumulate liver fat more readily than others due to the higher plasma insulin levels. The increased liver fat will cause relative resistance to insulin-suppression of hepatic glucose production. Over many years a modest increase in fasting plasma glucose level will cause increased basal insulin secretion rates as a homeostatic response. The consequent hyperinsulinemia will increase further the conversion of excess calories into liver fat. A vicious cycle of hyperinsulinemia and inadequate suppression of hepatic glucose production becomes established. Fatty liver leads to increased export of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) triacylglycerol which will increase fat delivery to all tissues including the islets. Excess fatty acid availability in the pancreatic islet impairs the acute insulin secretion in response to ingested food, and at a certain level of fatty acid exposure, dedifferentiation of the beta cell will occur with post-prandial hyperglycaemia. The hyperglycaemia will further increase insulin secretion rates, with secondary increase of hepatic lipogenesis, spinning the liver cycle faster and driving on the pancreas cycle. Eventually the fatty acid and glucose inhibitory effects on the islets reach a trigger level for dedifferentiation, leading to a relatively sudden onset of clinical diabetes. Figure adapted with permission from R Taylor.8