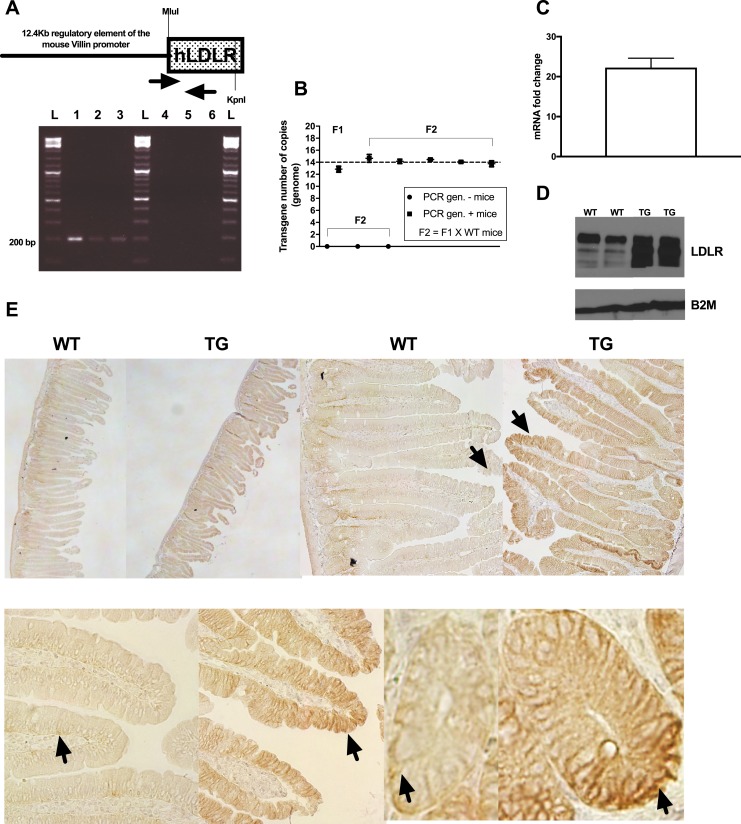

Figure 2.

Molecular characterization of the transgenic mouse line [C57BL/6-TG(Vil-LDLR)] of intestine-specific LDLR overexpression. (A) Schematic representation of the construct we used to generate the mice. MluI and KpnI restriction enzyme sites, which were used to clone the open reading frame of the human (h)LDLR gene, are shown. Primer location and representative genotyping results [(A), lower panel; anticipated PCR product, 195 bp] are shown. (B) Droplet PCR results obtained using F1 and F2 animals of known genotype. Transgene was stably transmitted over the generations in multiple (13, 14) copies. (C) Representative transgene and (D) LDLR protein expression levels in the duodenum of F2 animals (transgenic mice, n = 4; wild-type mice, n = 3). Data shown in (C) represent mean ± SD. (E) Immunohistochemical staining detected intestinal LDLR overexpression and located the transgene in the columnar epithelium and crypt cells. Representative sections of proximal intestinal sections stained against LDLR are shown. Upper panel: left to right, ×4 and ×10 original magnification of sections. Lower panel: details of villi and crypt cell staining (original magnification, ×40). Arrows indicate examples of areas with positive staining. 1, positive control (12.4-kb Villin-ΔATG-hLDLR plasmid DNA); 2, colony founder (F0); 3, F1 mouse (obtained by crossing F0 with C57BL/6 wild-type mice); 4, negative control (C57BL/6 wild-type mouse); 5, F1 mouse; 6, H2O; L, ladder; TG, C57BL/6-TG(Vil-LDLR) transgenic mice; WT, wild-type littermate controls.