Abstract

Chiral packing of ligands on the surface of nanoparticles (NPs) is of fundamental and practical importance, as it determines how NPs interact with each other and with the molecular world. Here, for gold nanorods (NRs) capped with end-grafted nonchiral polymer ligands, we show a new mechanism of chiral surface patterning. Under poor solvency conditions, an originally smooth polymer layer segregates into helicoidally organized surface-pinned micelles (patches). The unique helicoidal morphology is dictated by the polymer grafting density and the ratio of the polymer ligand length-to-nanorod radius, while outside this specific parameter space, small random and shish-kebob patches, as well as a uniformly thick polymer layer are formed. We characterize polymer surface morphology by the theoretical and experimental state diagrams. The helicoidally organized polymer patches on the NR surface can be used as a template for the helicoidal organization of other NPs, masked synthesis on the NR surface, as well as the exploration of new NP self-assembly modes.

Keywords: patchy nanoparticles, polymers, self-assembly, nanorods, patterning, helical

Graphical Abstract

For gold nanorods end-grafted with achiral polymer ligands, we show a new mechanism of chiral surface patterning. The helicoidal morphology is dictated by the relationship between the polymer grafting density and the ratio of the polymer length to the nanorod radius.

The subject of chirality is one of the most active research areas in nanoscience.[1] It can apply to individual nanoparticles (NPs),[2–7] NP assemblies,[8–11] and macroscopic chiral nematic phases formed by nanocolloids.[12] Chirality of individual NPs can originate from an asymmetric NP shape,[13–15] chiral ligands,[5,16,17] or chiral distribution of ligands on NP surface.[2,18] The latter type of chirality has direct implications for NP interactions with molecules and other NPs. For example, chiral ligand packing on the NP surface is directly linked to the generation of chiral “colloidal molecules” that can exhibit directional interparticle interactions and organize in chiral nanostructures.[11,19,20] Notably, chiral packing of ligands on the NP surface can occur with achiral molecules, as shown for achiral thiolates attached to the surface of gold clusters.[2] Alternatively, an asymmetric ligand shell formed due to a microphase separation on the NP surface[21,22] can also lead to induced chirality.[1]

Recently, we have proposed a new approach to the surface patterning of spherical NPs tethered with end-grafted polymer molecules.[23] Building on the predictions made for polymers end-grafted to a planar substrate,[24] we showed that upon transfer of polymer-capped NPs from a good to a poor solvent, an originally smooth polymer shell segregates into surface-pinned micelles (visualized as “patches” on the NP surface). These micelles have a dense core and stretched surface-pinned “legs.” The balance between the loss in energy due to the stretching of polymer ligands and the gain in energy due to polymer segregation in the micelle core determined the number, the dimensions, and the organization of the micelles on the NP surface.[23–25]

For NPs with non-spherical shapes, e.g., nanocubes,[26] triangular prisms,[27] or nanodumbells,[28] the site-specific NP surface curvature plays an important role in patch formation. Polymer patches formed on regions with a higher surface curvature, that is, on the vertices of triangular prisms, tips of nanodumbells, and vertices and edges of nanocubes.[23]

From this perspective, NPs with several local curvatures such as nanorods (NRs) represent an interesting system. Nanorods contain two distinct regions: a cylindrical segment and two semi-spherical tips (Figure 1a). The cylindrical segment is characterized by a zero curvature along the longitudinal axis and a positive curvature, κ = 1/r > 0, along the transverse axis,[29] where r is the transverse NR radius (the NR tips have a positive curvature along both axes).[30] In our earlier work,[23] we showed that for “short” gold NRs with the length comparable with the length of the stretched polymer ligands, in a poor solvent, the ligands stretch from the center of the cylindrical NR region towards the tips and engulf them with polymer patches. For the NRs that are significantly longer, it can be expected that polymer patches will form on the cylindrical NR segment, where the competition of curvatures would determine polymer morphology.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the NR functionalized with end-grafted polymer. (b) Schematic of symmetric polymer micelle (patch) with micelle core radius, R. The core and the dimensions of the “legs” are not given to scale. (c) Theoretical diagram of the polymer morphology on the cylindrical NR segment. Hemi-spherical tips of the NRs are omitted.

In the present work, we examined micelle (patch) formation on the surface of “long” NRs capped with end-grafted achiral polymer ligands (Figure 1b). For such NRs, under poor solvency conditions, we report a unique polymer morphology, that is, a helicoidal distribution of patches on the NR surface. This effect stems from the hexagonal packing of surface-pinned micelles on the NR surface and is driven by the asymmetric stretching of the polymer chains along the longitudinal and transverse NR axes. The helicoidal patch organization occurred for a specific range of polymer grafting density, σ, and the ratio of the polymer length-to-NR radius, r. Outside this range, random patch distribution, shish-kebab structures, hybrid structures, and a uniformly thick polymer “shell’ were formed. The distribution of patches on the NR surface was characterized by the theoretical and experimental state diagrams. The helicoidally organized patches can be used for the masked etching or site-specific organic or inorganic synthesis on the NR surface,[31–34] thus leading to new nanostructured materials. For example, attachment of semiconductor or graphene quantum dots to polymer-deprived NR surface regions can be used for studies of plasmonic-excitonic coupling.[35–37] In addition, new modes of self-assembly are expected for the NRs with the chiral distribution of attractive polymer surface patches.

First, we explored polymer morphology on the NR surface in a poor solvent theoretically by balancing the energy of polymer-solvent interactions and the elastic stretching energy of molecules forming surface-pinned micelles. At equilibrium, micelles exhibit dense hexagonal packing, as it insures the smallest average length of the micellar “legs” and thus their lowest stretching energy. Micelles with dimensions that are significantly smaller than the NR circumference have a symmetric footprint and “see” the NR surface as almost a planar substrate. In contrast, when micelles are substantially larger than the circumference of the NR, they elongate in the direction parallel to the long NR axis, to accommodate for the hexagonal organized footprints.

Figure 1c shows a theoretical diagram of states for the polymer-capped NR with a radius r, a circumference of the transverse cross-section, C = 2πr, and a NR length L >> r. The diagram is plotted on the double logarithmic scale in the lNp/r and σ coordinates, where l = 3 Å is the monomer length, and Np is the degree of polymerization of the ligands. Thus, lNp/r is the ratio between the polymer contour length and the NR radius. Inserts in Figure 1c illustrate polymer ligand morphology on the NR surface. A detailed description of the theoretical approach is given in the Supporting Information.

At a low σ and lNp/r ratios (in the lower left part of the diagram), the polymer ligands segregate into single-molecule globules. At low σ and intermediate lNp/r ratios (below the red line) pinned micelles with symmetric footprints are formed, which have an area A, a core radius R, and “leg” length ~A1/2 (R is symmetric with respect to the longitudinal and transverse NR axes). The area in the vicinity of the red line corresponds to the lNp/r ratios, in which the NR circumference, C, becomes comparable to the dimensions of micelle footprint. In this region, to cover the NR surface, micelle footprints elongate at the expense of “leg” stretching. At even larger lNp/r values and low σ (between the red line and the thick dashed line) the micelles have a strongly asymmetric footprint, since the transverse micelle dimensions are dictated by the cylinder circumference C << A1/2. These asymmetric micelles have a core radius (R⊥) perpendicular to the long NR axis and micelle leg length (R∣∣) parallel to the long NR axis. The micelles have a core radius R⊥ < r, elongated legs with length R∣∣, and an area ∼CR∣∣. Above the thick dashed line R⊥ ≈C, a “shish-kebab” polymer morphology with R⊥ >> r is expected, with pinned micelles wrapping around the NR. At high σ (to the right of vertical line R∣∣ ≈R⊥ and a boundary line A1/2 = R with a slope −2) polymer ligands collectively collapse and form a smooth layer with a thickness dependent on the lNp/r ratio.

The grey region of the diagram in the proximity of the boundary A1/2 = R delineates the regime, in which polymer micelles exhibit a helicoidal organization on the NR surface. A hexagonal micelle arrangement on the NR surface dictates the angle (that is, the inclination) between the long NR axis and the line passing through the centers of the nearest micelle cores (see Supporting Information). Micelles coalesce along this line and form continuous helicoidally shaped polymer structures on the cylindrical NR segment. This micelle arrangement optimizes the system free energy and requires corrections to scaling dependences. Notably, coalescence of pinned micelles on planar substrates with the formation of worm-like structures was observed in our earlier work.[38]

Next, we explored the segregation of polymer ligands on the NR surface experimentally. Gold NRs were synthesized using a method reported elsewhere[39,40] and subsequently, separated from small spherical NPs using depletion flocculation (Figure S1).[41–43] The NR length, L, and a transverse radius, r (Figure 1a) were in the range of 190–300 nm and 9–15 nm, respectively. Notably, the variation in the r values was considered to be an advantage, as it allowed for the variation in lNp/r, at a constant Np. Following the ligand exchange step, the cetyltrimethylammonium chloride ligands on the NR surface were replaced with thiol-terminated polystyrene (PS) molecules with the number average molecular weight, Mn, of 20 000, 50 000, 104 500, or 135 000 g/mol (with the degree of polymerization, Np, of 190, 480, 1000, and 1295, respectively). These polymers are denoted in the text below as PS-20K, PS-50K, PS-100K, and PS-135K, respectively. The ligand exchange was carried out in tetrahydrofuran, a good solvent for polystyrene.[44,45] Polymer grafting density, σ, on the NR surface was changed from 0.07 to 0.3 chains/nm2 by varying the ratio between the polymer concentration and the total NR surface area, during the ligand exchange procedure. In contrast to our earlier experiments, in which low-molecular weight ligands were replaced with PS molecules only on the NR tips,[46] in the present work, we used an excess of the PS in the ligand exchange process, in order to cap the entire NR surface.

The polymer-functionalized NRs were transferred to N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), a good solvent for PS, with the second virial coefficient, A2, of 3.5 × 10−4 mol cm3 g−2, equivalent to a Flory−Huggins interaction parameter, χ, of 0.46.[44,47] Polymer surface segregation into pinned micelles was triggered by reducing the quality of the solvent for the PS ligands by adding water to the NR solution in DMF to a final water concentration, Cw = 4 vol%. To suppress NR self-assembly in a poor solvent, we used a dilute (<1 nM) NR solution.

Figure 2 shows transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the most representative polymer morphologies on the cylindrical NR region. Based on the two-dimensional projections in the TEM images (top to bottom), we distinguished NRs with randomly distributed polymer micelles (a random patch, RP, regime), helicoidal patch (HP) arrangement, and a smooth polymer layer corresponding to a core-shell (CS) structure. We also observed a small fraction of NRs coated with shish-kebab patches (SP), and a hybrid structure of HP, CS, and SP polymer morphologies (see Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

TEM images of PS-coated NRs in the DMF/water mixture at Cw = 4 vol% at (a-c) σ = 0.2 chain/nm2 and lNp/r (top-to-bottom) of 5 (PS-20K), 12 (PS-50K), and 29 (PS-135K), respectively, and (d-f) at lNp/r = 14 (PS-50K) with σ (top-to-bottom) of 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2 chain/nm2, respectively. Scale bars are 100 nm.

At constant σ, with an increasing lNp/r ratio, a gradual transition occurred from small and discrete random polymer patches to the helicoidally organized polymer patches. The handedness of the helical patch arrangement was not possible to determine, however, given that there is no driving force for the selection of a particular enantiomer, we speculate that a racemic mixture was obtained. Further increase of the lNp/r ratio, yielded a smooth polymer layer on the NR surface, that is, a CS structure (Figure 2a-c). Similarly, at a constant lNp/r, with an increasing σ and, we observed the RP→HP→CS transitions in polymer morphology on the NR surface (Figure 2d-f).

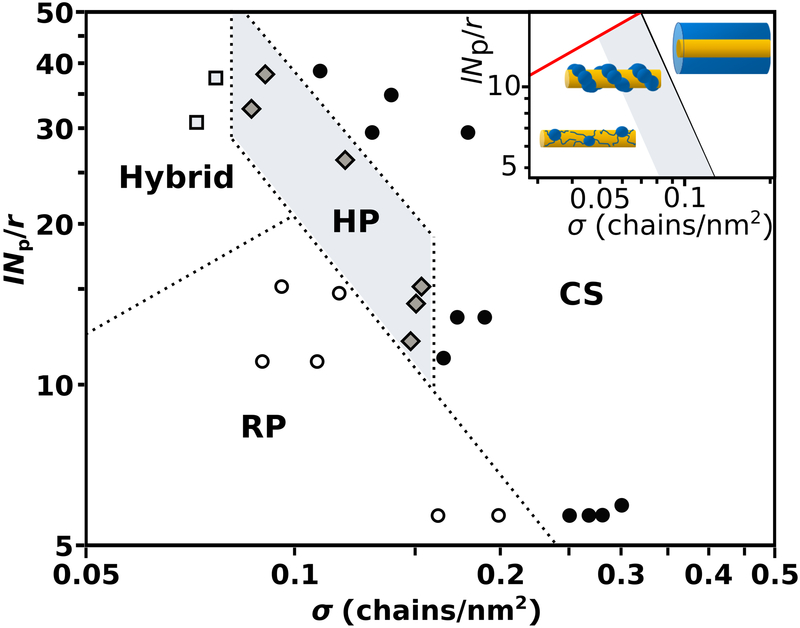

The structural transitions in polymer morphology on the cylindrical NR surface were mapped on the experimental diagram of states, plotted on a double logarithmic scale in the experimental σ and lNp/r coordinates (Figure 3). At low σ and low-to-intermediate lNp/r values, a large region of the diagram reflected the formation of small random patches (RP). At high σ, a CS structure was favored, with a negative slope of the boundary between the “patchy” (RP and HP) and CS regions. This feature signified the importance of the transverse NR curvature: for low lNp/r ratios polymer segregation was observed at higher σ values. A well-defined HP region in the center of the diagram signified the formation of helicoidal structures at intermediate and high lNp/r values (highlighted with grey color). At lowσ and high lNp/r values, polymer segregation became less defined and hybrid HP, CS and SP polymer morphologies were observed (designated as “SP/CS” in Figure 4a).

Figure 3.

Experimental diagram of polymer morphology states plotted in the lNp/r and grafting density σ coordinates. The ratio INp/r was changed by varying the molecular weight of the polymer ligands from PS-20K to PS-135K and accounting for the NR radius r measured for each sample. The inset shows a fragment of the theoretical state diagram pertinent to experimental diagram.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the HP on the NR surface. (a) Histogram of polymer morphologies at σ = 0.15 chains/nm2, PS-50K, and lNp/r of 12-15. (b) Variation in the number of turns with the length of the NR. Insets show NRs with L = 153 and 226, and n = 1 and 3, respectively. The corresponding data points are represented by the hollow points. Scale bars are 100 nm.

Analysis of the TEM images of the helicoidal structures indicated that the NR circumference C was close to the distance between the “humps” in the helicoidal structures and approximately two-fold larger than the micellar core radius R. The latter observation indicated that the examined morphologies were close to the boundaries A1/2 ≈ C and A1/2 = R in the theoretical diagram of states. Thus, the experimental diagram in Figure 3 represented the regimes of pinned micelles with a symmetric footprint and a homogeneous core-shell cylindrical layer separated with a region of helical structures. This fragment of the theoretical state diagram (shown as inset in Figure 3) was in agreement with experimental results

Next, we examined in greater detail the helicoidal organization of polymer patches formed by PS-50K on the NR surface. The histogram in Figure 4a shows that at σ = 0.15 chains/nm2 and lNp/r of 14.5 ± 1.6, 53% of the NRs were coated with helicoidally organized polymer patches, while RP, SP, SP/CS hybrid, and CS morphologies were observed on 16, 13, 5, and 13% of the NRs, respectively.

The number of turns, n, for the helicoidal patch organization was determined as n = L/p, where p = 79 nm is the average pitch (measured as the distance between the centres of adjacent polymer patches residing on the same NR side), as shown in Figure 4b. Figure 4b shows that the number of turns increased from 1.3 to 4.7, when the NR length increased from 136 to 267 nm at r of 20–24 nm.

We also characterized the aspect ratio of HPs as the ratio of the patch length (parallel to the NR long axis) and height. For HPs formed by PS-50K, PS-100K, and PS-135K, the aspect ratio remained constant at 2.1 ± 0.5 for a broad range of lNp/r values, in agreement with theoretical predictions (see Supporting Information).

The approach to the helicoidal micelle (patch) formation on the NR surface is schematically illustrated in Figure 5. On a planar surface, pinned micelles with a symmetric footprint exhibit hexagonal packing (Figure 5a). With an increasing NR surface curvature κ = 1/r, the footprint of micelles elongates in the direction parallel to the NR long axis, mostly, at the expense of stretched micelle legs (Figure 5b). With further increase in NR curvature, the elongated micelles (patches) the lines connecting the centers of the nearest micelles form an angle (that is, incline) with respect to the NR long axis and coalesce along the line of the shortest distance between them (Figure 5c). The transitions shown in Figure 5b and c occur at a specific range of polymer grafting densities σ and the ratio between the polymer length and the NR radius lNp/r

Figure 5.

Schematics of the formation of the helicoidal polymer structures on the NR surface with increasing curvature κ = 1/r). The region outlined in red corresponds to the micelle footprint with an area A.

To summarize, we show that in poor solvency conditions end-grafted polymer ligands on the cylindrical segment of gold NRs form helicoidally organized surface patches. This surface morphology is realized by varying the relationship between the (i) the polymer grafting density and (ii) the ratio between the between the polymer length (that is, polymer molecular weight) and the NR radius. Outside this parameter space, a range of polymer surface structures was observed, including small random, shish-kebab and hybrid patches, as well as a smooth polymer layer. The transitions were presented on an experimental diagram of states, which was agreement with a theoretical diagram. The helical structures of PS-50K had a pitch of 79 nm and a constant aspect ratio, in agreement with theoretical predictions.

The helicoidal polymer patches on the NR surface can be used as masks for the synthesis of hybrid NPs with complex structures and compositions.[31–34] Site-selective attachment of small semiconductor NPs to the polymer-deprived NR regions can be used for studies of plasmonic-excitonic coupling.[35–37] In addition, new modes of self-assembly are expected for the NRs with the chiral distribution of attractive polymer patches. Future experiments will address the ability to characterize and control the handedness of the helicoidal nanostructures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

EK acknowledges the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC, Discovery and Canada Research Chair programs). EG thanks NSERC for the Alexander Graham Bell Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGS-D). HT acknowledges Connaught International Scholarship. MR acknowledges financial support from National Science Foundation under Grants DMR-1121107 and EFMA-1830957, the National Institutes of Health under Grants P01-HL108808, R01-HL136961, and 5UH3HL123645, and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. EBZ acknowledges financial support from the Russian Ministry of Education and Science (State Contract 14.W03.31.0022).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].Ma W, Xu L, De Moura AF, Wu X, Kuang H, Xu C, Kotov NA, Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8041–8093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dolamic I, Knoppe S, Dass A, Bürgi T, Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gautier C, Bürgi T, ChemPhysChem 2009, 10, 483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schaaff TG, Knight G, Shafigullin MN, Borkman RF, Whetten RL, J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 10643–10646. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gautier C, Bürgi T, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 11079–11087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lu F, Tian Y, Liu M, Su D, Zhang H, Govorov AO, Gang O, Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 3145–3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Slocik JM, Govorov AO, Naik RR, Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 701–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Holmes DF, Gilpin CJ, Baldock C, Ziese U, Koster AJ, Kadler KE, Corneal Collagen Fibril Structure in Three Dimensions: Structural Insights into Fibril Assembly, Mechanical Properties, and Tissue Organization, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lilly GD, Agarwal A, Srivastava S, Kotov NA, Small 2011, 7, 2004–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ma W, Kuang H, Xu L, Ding L, Xu C, Wang L, Kotov NA, Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, DOI 10.1038/ncomms3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lu J, Chang YX, Zhang NN, Wei Y, Li AJ, Tai J, Xue Y, Wang ZY, Yang Y, Zhao L, et al. , ACS Nano 2017, 11, 3463–3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li Y, Jun-Yan Suen J, Prince E, Larin EM, Klinkova A, Thérien-Aubin H, Zhu S, Yang B, Helmy AS, Lavrentovich OD, et al. , Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, DOI 10.1038/ncomms12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ben-Moshe A, Wolf SG, Sadan MB, Houben L, Fan Z, Govorov AO, Markovich G, Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, DOI 10.1038/ncomms5302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yeom J, Yeom B, Chan H, Smith KW, Dominguez-Medina S, Bahng JH, Zhao G, Chang WS, Chang SJ, Chuvilin A, et al. , Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee HE, Ahn HY, Mun J, Lee YY, Kim M, Cho NH, Chang K, Kim WS, Rho J, Nam KT, Nature 2018, 556, 360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nakashima T, Kobayashi Y, Kawai T, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 10342–10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Humblot V, Haq S, Muryn C, Hofer WA, Raval R, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li Y, Yu D, Dai L, Urbas A, Li Q, Langmuir 2011, 27, 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bianchi E, Blaak R, Likos CN, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 6397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Marshall BD, Soft Matter 2017, 13, 6506–6514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Singh C, Ghorai PK, Horsch MA, Jackson AM, Larson RG, Stellacci F, Glotzer SC, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rossner C, Tang Q, Müller M, Kothleitner G, Soft Matter 2018, 14, 4551–4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Choueiri RM, Galati E, Thérien-Aubin H, Klinkova A, Larin EM, Querejeta-Fernández A, Han L, Xin HL, Gang O, Zhulina EB, et al. , Nature 2016, 538, 79–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhulina EB, Birshtein TM, Priamitsyn VA, Klushin LI, Macromolecules 1995, 28, 8612–8620. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Choueiri RM; Klinkova A, Pearce A;S, Manners I, Kumacheva E. Macromol. Rapid Comm. 2018, 39, 1700554 10.1002/marc.201700554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Galati E, Tebbe M, Querejeta-Fernández A, Xin HL, Gang O, Zhulina EB, Kumacheva E, ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4995–5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jones MR, Macfarlane RJ, Prigodich AE, Patel PC, Mirkin CA, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18865–18869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Walker DA, Leitsch EK, Nap RJ, Szleifer I, Grzybowski BA, Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 676–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nerlich G, in Shape Sp, Press Syndics Of University Of Cambridge, Cambridge, 1994, pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gonzalez Solveyra E, Tagliazucchi M, Szleifer I, Faraday Discuss. 2016, 191, 351–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cathcart N, Mistry P, Makra C, Pietrobon B, Coombs N, Jelokhani-Niaraki M, Kitaev V, Langmuir 2009, 25, 5840–5846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bierman MJ, Lau YKA, Kvit AV, Schmitt AL, Jin S, Science 2008, 320, 1060–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wang Y, Wang Q, Sun H, Zhang W, Chen G, Wang Y, Shen X, Han Y, Lu X, Chen H, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20060–20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang Z, He B, Xu G, Wang G, Wang J, Feng Y, Su D, Chen B, Li H, Wu Z, et al. , Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Abdulrahman NA, Fan Z, Tonooka T, Kelly SM, Gadegaard N, Hendry E, Govorov AO, Kadodwala M, Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 977–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li Z, Zhu Z, Liu W, Zhou Y, Han B, Gao Y, Tang Z, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3322–3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Husu H, Canfield BK, Laukkanen J, Bai B, Kuittinen M, Turunen J, Kauranen M, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tebbe M, Galati E, Walker GC, Kumacheva E, Small 2017, 13, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sánchez-Iglesias A, Winckelmans N, Altantzis T, Bals S, Grzelczak M, Liz-Marzán LM, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Jana NR, Gearheart L, Murphy CJ, J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 4065–4067. [Google Scholar]

- [41].The pentatwinned geometry of the NRs was assumed to be screened by the long polymer ligands with respects to the NR radius.

- [42].Mayer M, Scarabelli L, March K, Altantzis T, Tebbe M, Kociak M, Bals S, Garciá De Abajo FJ, Fery A, Liz-Marzán LM, Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 5427–5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Park K, Koerner H, Vaia RA, Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1433–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rubinstein RM, Colby M, Polymer Physics, Oxford, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Schulz GV, Baumann H, Makromol. Chem. 1968, 114, 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nie Z, Fava D, Kumacheva E, Zou S, Walker GC, Rubinstein M, Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wolf BA, Blaum G, Makromol. Chem. 1978, 179, 2265–2277. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.