Abstract

pH is an important factor that affects the protein structure, stability, and activity. Here, we probe the nature of the low-pH structural form of the homodimeric CcdB (controller of cell death B) protein. Characterization of CcdB protein at pH 4 and 300 K using circular dichroism spectroscopy, 8-anilino-1-naphthalene-sulphonate binding, and Trp solvation studies suggests that it forms a partially unfolded state with a dry core at equilibrium under these conditions. CcdB remains dimeric at pH 4 as shown by multiple techniques, such as size-exclusion chromatography coupled to multiangle light scattering, analytical ultracentrifugation, and electron paramagnetic resonance. Comparative analysis using two-dimensional 15N-1H heteronuclear single-quantum coherence NMR spectra of CcdB at pH 4 and 7 suggests that the pH 4 and native state have similar but nonidentical structures. Hydrogen-exchange-mass-spectrometry studies demonstrate that the pH 4 state has substantial but anisotropic changes in local stability with core regions close to the dimer interface showing lower protection but some other regions showing higher protection relative to pH 7.

Introduction

Electrostatic interactions in proteins play a vital role in protein stabilization (1, 2, 3, 4). pH is a common modulator of electrostatic interactions and thus the stability of the proteins (5, 6, 7, 8). pH often induces the formation of a globular state with a molten core, widely known as a molten globule (MG) (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14). MGs have nearly intact secondary structure but have marginally or significantly reduced tertiary structure relative to the native state (15, 16, 17). MGs have been classified as wet MG (WMG) and dry MG (DMG), where the latter has a dehydrated core. In WMGs, water has penetrated the hydrophobic core of the protein, hence it is more expanded (16). The WMG state is relatively well characterized by high-resolution probes such as NMR (10, 18) and hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HX) (19, 20, 21, 22). Many proteins, such as α-lactalbumin (17, 23), cytochrome-c (24), apomyoglobin (18), various periplasmic binding proteins (14, 25), and flavodoxin (26), readily undergo solvent-induced structural transitions to form a WMG in equilibrium conditions (16, 27). In contrast, the DMG state has been predominantly detected during kinetic studies of protein unfolding (28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33) with few reports under equilibrium (4, 26, 31).

In this report, we present a characterization of the structural state of the homodimeric Escherichia coli toxin, controller of cell death B (CcdB) at pH 4, hereafter referred to as CcdB_4. The folding (34) and thermodynamics (35) of CcdB have been studied previously, where it was believed to be monomeric at pH 4 based on size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) (35). In this work, further characterization of this state of the protein was undertaken using probes like SEC coupled to multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), and analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC), which clearly show that it is in fact dimeric at both pH 4 and 7. Structural characterization using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, Red Edge Excitation Shift (REES), and ANS binding suggest that the dimeric form of CcdB at pH 4 has molten-globule-like properties. Further, investigation using tryptophan fluorescence and measurement of solvent accessibility of tryptophan using acrylamide quenching suggests that the core of the pH 4 state is dry. Characterization using 2D NMR suggests that CcdB_4 retains a globular structure that is similar but nonidentical to the native state, whereas the EPR and anisotropy data suggest that it is expanded relative to the native state. CcdB_4 was also investigated using Hydrogen Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HX-MS). Results suggest that CcdB_4 is highly dynamic as compared to the native state.

Materials and Methods

D2O with 99.9% Deuterium content was purchased from Board of Radiation and Isotope Technology (Navi Mumbai, India). All other reagents used were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and were of the highest purity grade. For additional details on methods please see the Supporting Materials and Methods.

Protein preparation

CcdB was expressed from pBAD24 vector in E. coli strain CSH501 and purified as described previously (34). The purity of the protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry. 15N labeled CcdB was prepared using the same expression system and purification method. The CSH501 cells were grown overnight at 37°C in M9 medium containing glycerol as the sole carbon source and diluted 100-fold into M9 medium containing 1% 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source and glycerol as the sole carbon source. The culture was induced at an optical density 600 nm was 2.5 using 2% w/v arabinose. The culture was grown for 24 h at 37°C post induction before harvesting the cells. Purification of the protein was carried out as described previously (34). Controller of cell death A (CcdA) peptides used in these studies were synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ).

CD spectroscopy

Spectroscopic characterization of CcdB at pH 4 (20 mM sodium acetate) and pH 7 (10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid [HEPES]) using CD were carried out on a Jasco J-815 Spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Easton, MD). Far-UV (ultraviolet) CD spectra of CcdB were acquired using a cuvette of 1 mm pathlength at 15–20 μM protein concentration, whereas near-UV CD spectra were acquired using a cuvette of 10 mm path length at 150 μM protein concentration. All CD spectra represent the average of 15 spectra obtained at 50 nm/min scan speed using 2 s integration times. All CcdB concentrations reported are in monomer units.

Fluorescence measurements and dynamic quenching studies

Fluorescence spectra of CcdB at pH 4 and pH 7 under native conditions were acquired using an excitation wavelength of 295 nm with 1 nm bandwidth, where emission was collected from 300 to 400 nm with 10 nm bandwidth. Spectra were collected using 1 nm data pitch with an integration time of 2 s at each data point. All spectral measurements were carried out using a Fluoromax-3 spectrofluorometer from Horiba Scientific (Piscataway, NJ).

To measure the dynamic quenching of CcdB, the protein was incubated in the presence of various concentrations of acrylamide ranging from 0 to 0.6 M concentration. Fluorescence of the intrinsic tryptophan residues of CcdB was measured in the absence (F0) and in the presence (F) of acrylamide using an excitation wavelength of 295 nm at 1 nm bandwidth, and fluorescence emission was collected at 340 nm at 10 nm bandwidth. The data were plotted as F0/F as a function of acrylamide concentration (Q) and were analyzed using the Stern-Volmer equation (Eq. 1), where KSV represents the Stern-Volmer constant.

| (1) |

NMR sample preparation

15N-labeled CcdB protein was prepared at 200 μM concentration in 10 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7 and in 20 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 4. Two-dimensional (2D) 15N-edited NMR experiments were carried out in 90% H2O and 10% D2O. The pH values are uncorrected for isotopic effects.

NMR data acquisition

NMR spectra were acquired using a Varian DDS2 600 MHz spectrometer (Agilent Technologies; Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a triple resonance cold probe. The spectra were recorded at 30°C. Water suppression and frequency selection in 15N-edited NMR experiments was achieved using coherence selection and sensitivity enhancement via gradients. The chemical shifts were referenced using external 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid. Proton spectral widths of 8012.8 Hz in the acquired dimension and 2188.2 Hz in the indirectly detected dimension were used to record 1H−15N HSQC spectra (36) at 600 MHz.

EPR measurements

The double-quantum coherence (DQC) and Ku-band double electron-electron resonance (DEER) measurements were carried out with spin-labeled proteins using the single cysteine variant of CcdB-R13C.

Spin labeling was performed under dark conditions. For spin labeling, 2 mg of purified protein was treated for 2 h with 450 μL of a 10% dithiothreitol solution to reduce any oxidized cysteine; dialyzed against citrate, glycine, and HEPES (5 mM each) buffer to remove excess dithiothreitol; and finally incubated with an addition of (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-pyrroline-3-methyl)-methanethiosulfonate in a threefold molar excess under slight rotation for 12 h. After another dialysis against citrate, glycine, and HEPES (5 mM each) buffer, the spin-labeled protein samples were shock frozen, stored in liquid nitrogen, and used directly for EPR experiments.

Pulsed dipolar EPR spectroscopy experiments on CcdB samples were performed at 60 K and 17.3 GHz frequency using a home-built Ku-band pulsed dipolar EPR spectroscopy spectrometer at the National Biomedical Center for Advanced Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) Technology (37, 38). Samples were measured by DQC (39) and DEER (40, 41) using the six-pulse DQC sequence π/2-tp-π-tp-π/2-td-π-td-π/2-(tm-tp)-π-(tm-tp)-echo and the four-pulse DEER sequence π/2(νobs)-t-π(νobs)-t-π(νpump)-(2τ-t)-π(νobs)-τ-echo for all conditions. DQC used π/2 and π pulses of 3 and 6 ns, respectively, and the sequence was applied at the center of the spectrum. DEER used 16 and 32 ns pulses for detection (νobs) and 16 ns pump pulse (νpump). The setup for DEER was standard with the detection sequences applied at the low-field edge of the spectrum (42). DQC and DEER data were collected usually in 1–4 h and are shown in Fig. S1. The time-domain DEER data and distance distributions were in very good agreement with the respective DQC data and distance distributions. This also indicated that these details were unlikely to originate from (usually weak) orientation effects. The L-curve Tikhonov regularization (43) followed by the refinement with the maximum-entropy method (44) was used for distance reconstruction.

ANS binding assay

ANS (8-anilino-1-naphthalene-sulphonate) binding studies were carried out using 10-fold molar excess of ANS at 1 μM CcdB concentration at pH 4 and pH 7 in citrate, glycine, and HEPES (10 mM each) buffer. The protein was incubated for 30 min before fluorescence measurement, where the fluorescence emission was monitored at 475 nm upon excitation at 388 nm. A previously characterized MG of maltose-binding protein (MBP) (14, 45) was tested for ANS binding as a positive control. ANS binding was also measured with a control CcdA46–72 peptide, comprising of residues 46–72 of the CcdA protein.

Hydrogen-exchange mass spectrometry

Purified CcdB protein was lyophilized and resuspended in 10 mM HEPES buffer prepared in D2O at pD7. The protein was fully deuterated by incubating it at 45°C for 15 h. The hydrogen exchange process was initiated by diluting protein in a buffer prepared in H2O at a final pH value of 4 or 7. The exchange was allowed to proceed for various times at 37°C and was subsequently quenched by lowering the pH to 2.6 using an ice-cold Glycine-HCl buffer. The quenched sample was analyzed using a liquid-chromatography (LC)-mass-spectrometry system. The LC processing was performed using an Agilent LC system (Infinity 1260; Santa Clara, CA), whereas the mass spectra were acquired on a Bruker Maxis Impact mass spectrometer using the electrospray ionization mode (Bruker, Billerica, MA).

The mass spectrometry analysis was performed with intact protein and with the proteolytic peptides generated after native-state hydrogen exchange of intact protein. The peptides were generated using an online pepsin column in the LC system from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). The generated peptides were separated using a Waters nanoAcquity LC system (Milford, MA) and analyzed using Waters Synapt G2 High Definition mass spectrometer. Identification of protein segments was aided by Waters ProteinLynx Global SERVER software and was also verified using manual inspection.

Calculation of protection value

The protection values were calculated using the following equation (46):

| (2) |

In Eq. 2, a is the amplitude that represents the number of protected amides and τ is the observed time constant of the hydrogen exchange process. n represents the number of phases of exchange process, which ranges from 1 to 3 for different peptides.

SEC-MALS

The oligomeric status of CcdB was determined by MALS analysis coupled to gel filtration chromatographic separation. Gel filtration chromatographic separation was carried out using a Superdex-75 column having a bed volume of 24 mL (General Electric Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) coupled to a Shimadzu pump (Kyoto, Japan). Chromatographic separation at pH 7 was carried out using 10 mM HEPES containing 200 mM NaCl, whereas separation at pH 4 was carried out using 10 mM sodium acetate buffer containing 200 mM NaCl. Buffers were filtered using a 0.1 μm pore-sized filter (Millipore, Burlington, MA) and degassed thoroughly. Analyses were done using 100 μL of 60 μM CcdB (∼75 μg) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min in the respective buffer. In each case, the molarity is in terms of monomer units. The SEC column was coupled in line with the following calibrated detectors: 1) a UV detector (Shimadzu), 2) a MiniDawn Treos MALS (Wyatt, Goleta, CA), and 3) a 2414 Refractive Index detector (Waters). The Astra V software (Wyatt) was used to combine these measurements to determine the absolute molar mass of the eluted protein.

Results and Discussion

Current understanding about the structure and dynamics of the MG is poor. We have limited understanding about how the MG differs from the native state, the extent of reduced packing interactions, and how this affects its dynamics.

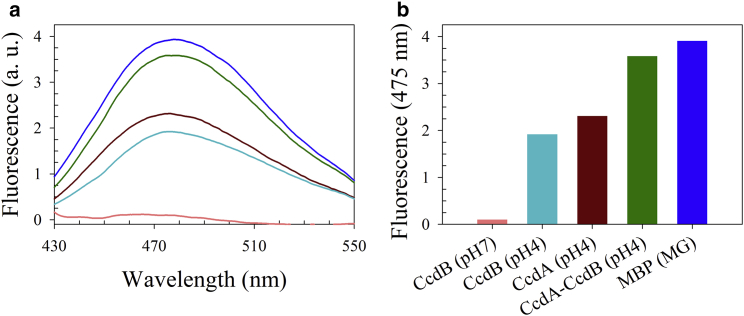

CcdB_4 is partially unfolded

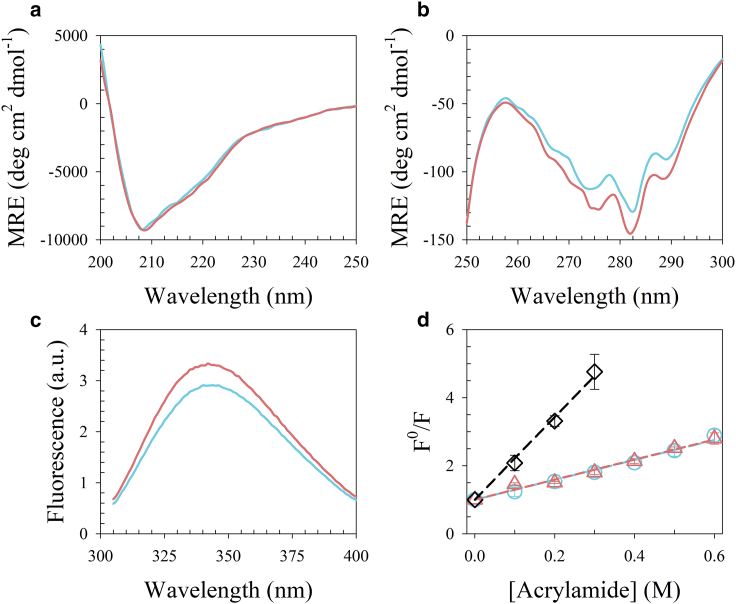

To probe the structural state of CcdB at pH 4, spectroscopic characterization was undertaken using far-UV CD and near-UV CD. The far-UV CD spectra of CcdB at pH 4 and 7 are identical (Fig. 1 a), whereas the near-UV CD spectrum of CcdB at pH 4 shows a positive change in ellipticity relative to that at pH 7 of ∼20% between 260 and 290 nm (Fig. 1 b). Outside this range, CcdB appears to have identical molar residue ellipticity at both pH values. These results suggest that at pH 4, CcdB undergoes a transition that results in a structural form having identical secondary structure but decreased tertiary structure from the native state. Such structural transitions are observed during formation of the MG state (9, 12, 13, 17). ANS binding studies were carried out. The folded dimer of CcdB at pH 7 failed to bind to ANS, whereas the pH 4 form binds to ANS (Fig. 2), which suggests that CcdB at pH 4 has exposed hydrophobic patches. MBP is a positive control, known to form an MG at low pH (14, 45). The CcdA46–72 is a peptide that is known to bind CcdB. This also binds ANS at pH 4, and this ANS binding appears to be retained in the CcdB-CcdA46–72 complex at pH 4.

Figure 1.

Structural characterization of CcdB using various probes at pH 4 (cyan) and pH 7 (pink). (a) and (b) show far-UV and near-UV CD spectra of CcdB, respectively. (c) Fluorescence emission spectra of intrinsic tryptophan residues of CcdB obtained using an excitation wavelength of 295 nm are shown. (d) Stern-Volmer plot for native CcdB obtained at pH 4, pH 7, and unfolded CcdB (black). Fluorescence of CcdB in the absence of quencher, relative to the fluorescence obtained at various concentrations of acrylamide quencher, is plotted as a function of acrylamide concentration. The dashed line through the data in the respective color represents the fit to the data using Eq. 1. The error bars represent standard error from two or more independent experiments. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 2.

Characterization of ANS binding to CcdB at pH 4 and 7. (a) and (b) show fluorescence spectra and fluorescence intensity at 475 nm, respectively, for CcdB, CcdA, and MBP (maltose-binding protein) in the presence of ANS. CcdB binds ANS only at pH 4 (cyan) and not at pH 7 (pink). The CcdA peptide (residues 46–72) is reported to be largely unstructured yet shows comparable ANS binding (brown) to CcdB at pH 4. The CcdA-CcdB complex (green) at pH 4 also binds to ANS, suggesting CcdB retains exposed hydrophobic patches even in complex with CcdA. Also shown as a positive control are data for the molten globule (MG) of MBP (blue), which is known to bind ANS. To see this figure in color, go online.

CcdB_4 has a dry core

Further characterization of the CcdB_4 was carried out to evaluate the solvation of its hydrophobic core by monitoring intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. The Stokes shift of tryptophan is sensitive to its environment. A blueshift is observed when it moves to the hydrophobic core of the protein from the polar solvent. Thus, the fluorescence spectrum of buried tryptophan reveals the extent of penetration of water into the core of the protein. Each CcdB monomer has two partially buried tryptophan residues at positions 61 and 99, which have solvent accessibilities of 11 and 20%, respectively (Fig. S2), and depth (47) of 5.4 and 5 Å, respectively. The fluorescence spectrum of CcdB at pH 7 has an emission maximum at 340 nm (Fig. 1 c), which is significantly blue shifted compared to the emission maximum of a solvent-exposed tryptophan residue. The fluorescence spectrum of CcdB acquired at pH 4 also has an emission maximum of fluorescence at 340 nm (Fig. 1 c), identical to that of the pH 7 form. The results suggest that the core of CcdB at pH 4 is as dry as that at pH 7.

Dynamic fluorescence quenching studies were carried out to probe the change in solvent accessibility of the tryptophan residues in CcdB at low pH. Acrylamide quenches the fluorescence of tryptophan, where the extent of quenching depends on the concentration of quencher and solvent accessibility of the tryptophan (48, 49). The fluorescence of CcdB was measured in the absence (F0) and presence (F) of acrylamide, and the ratio of the two (F0/F) was plotted as a function of acrylamide concentration (Q) (Fig. 1 d). The linear F0/F versus Q plots were analyzed using Eq. 1, also known as the Stern-Volmer equation (49). The parameters derived from the analysis are shown in Table S1. The values of the Stern-Volmer constant (KSV) of native CcdB at pH 4 and 7 are identical, implying that tryptophan residues have identical solvent accessibility under both conditions. The values of the KSV suggest that both the tryptophan residues of CcdB are significantly buried (9, 50). The KSV of the unfolded CcdB at pH 4 is significantly higher than that of the native CcdB at pH 4 (Table S1), confirming that the core of CcdB at pH 4 and pH 7 in aqueous buffer is significantly dry compared to that of its unfolded state. Together, these results strongly suggest that CcdB in the absence of denaturant at pH 4 indeed populates a form with a dry core, albeit one that can still bind to ANS. It is possible that ANS binding is facilitated by localized structure opening, whereas most of the core remains isolated from the solvent.

We further investigated the environment around the tryptophan residues using the REES (red-edge excitation shift) experiment (51, 52, 53) to understand the nature of the core of the protein. Normally, in a homogenous solvent, the fluorophore emission maximum remains independent of the excitation wavelength. However, in a heterogenous viscous environment, it shows dependence when excited at the red edge of the excitation spectrum (51, 52, 53). The fluorescence spectrum of CcdB at pH 4 shows a 3–4-nm red shift in emission maximum upon varying excitation wavelengths from 295 to 305 nm (Fig. S3 a). In contrast, emission spectra remain unchanged when unfolded CcdB at pH 4 was excited at different wavelengths (Fig. S3 b). The results suggest that tryptophan residues of CcdB at pH 4 are in a heterogenous, viscous environment. We also carried out REES analysis of CcdB at pH 7 under native conditions (Fig. S3 c), which resulted in only a marginal shift of ∼1 nm. The results suggest that the CcdB interior at pH 4 behaves as a viscous liquid-like solvent, whereas it is relatively more rigid at pH 7.

pH-induced stabilization of the MG state has been observed in other proteins. In the case of CcdB_4, protonation of histidine, aspartate, and glutamate residues could be playing an important role in stabilizing the pH 4 state (20). It should be noted that studies described above monitored the hydration state of the two tryptophan residues as an indirect measure of hydration state of the core. Because these two tryptophan residues are located in the core of the protein, but are far apart from each other (Fig. S2), lack of hydration of both the tryptophan residues indicates a high likelihood that the entire core of the protein is dry. The similarity of the NMR spectra (see later section) is consistent with this assertion.

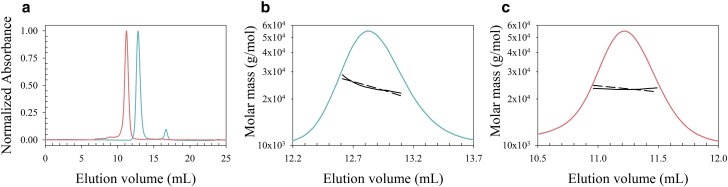

CcdB is dimeric at pH 4

Previous studies reported CcdB to be monomeric based on gel filtration analysis (35). Therefore, it was important to verify the oligomeric state of CcdB at pH 4. The oligomeric state of the protein was investigated using three different approaches: SEC-MALS, EPR, and AUC. The SEC-MALS analysis was carried out with CcdB at pH 4 and pH 7, where, consistent with the previous findings (35), CcdB had a greater elution volume at pH 4 than at pH 7. At pH 4, the elution volume of CcdB corresponds to an apparent molecular mass of ∼13 kDa, which is closer to the expected mass of the monomer (11.7 kDa) (Fig. 3 a). However, when the peaks on the gel filtration column were analyzed by MALS, it was seen that the molecular weight of the pH 4 form matched that of the pH 7 form, that is, the dimeric form (Fig. 3, b and c). It was seen that CcdB_4 interacts with the dextran matrix, resulting in an increased retention volume on the gel filtration column.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the oligomeric state of CcdB using SEC-MALS. (a) An SEC chromatogram of CcdB at pH 4 (cyan) and pH 7 (pink) monitored using absorbance at 280 nm is shown. The SEC was carried out using an S-75 column with 60 μM (75 μg) of CcdB. CcdB at pH 4 has a higher elution volume than at pH 7. (b) and (c) show the molar mass obtained from the relevant peak at pH 4 and pH 7, respectively. The solid black line indicates the molecular weight averaged across the peak, whereas the dashed black line is the fit to the data. CcdB at pH 7 has a mass of 23.4 kDa, as expected. The pH 4 form also yields a mass of 24 kDa, consistent with a dimer. To see this figure in color, go online.

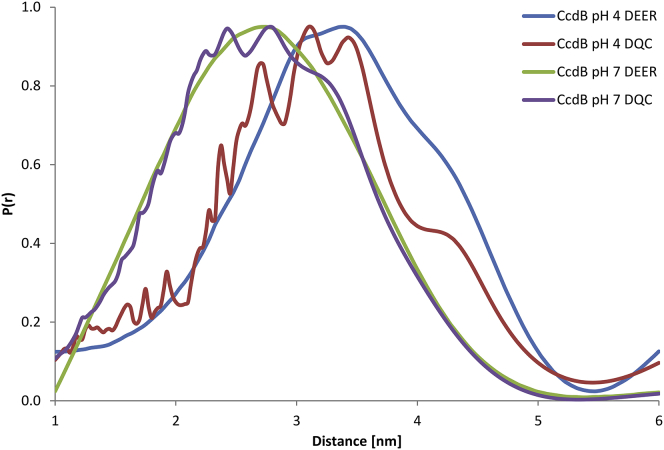

The EPR results are also consistent with the dimeric nature of CcdB at pH 4. The R13C variant of CcdB with a single cysteine was labeled with methanethiosulfonate to perform EPR measurements. Depending on the conformation of the probes, molecular dynamics simulation predicted the distance between the spin labels on adjacent monomers to range from 20 to 45 Å (Fig. S4). The DEER and DQC measurements of CcdB at pH 4.2 and 7 yielded mean distances of 32 and 27 Å, respectively (Fig. 4), confirming the dimeric nature of the protein at both pH values. The difference in distances at pH 4 and 7 suggest that CcdB undergoes an expansion upon change in the pH.

Figure 4.

Normalized DQC and DEER EPR spectra of CcdB at pH 7.0 and pH 4.0. Note the changes in the distance distribution between the two forms as revealed by dipolar interactions within the dimer, exhibiting an apparent loosening/opening of the structure in the CcdB_4 state. To see this figure in color, go online.

The SEC-MALS and EPR results were corroborated by AUC studies. The major advantage of AUC is that it can determine mass distributions and globularity without the use of standards or interactions with a size-exclusion matrix. Sedimentation velocity studies were done on CcdB at both pH 7 and pH 4 (Fig. S5, a and b). The van Holde-Weischet analysis helps distinguish between transport due to diffusion and transport due to sedimentation (54, 55). It showed that in case of both the pH 7 and pH 4 samples (Fig. S5 c), the sedimentation coefficient is ∼2.2 × 10−13 s. Both samples show a molecular weight of ∼25 kDa, which is similar to the expected dimeric mass of 23.4 kDa (Fig. S6, a and c). The frictional ratio of this solute, which is one for a perfect sphere, is 1.3 for CcdB at both pH 7 and 4 (Fig. S6, b and d). These results suggest that the CcdB_4 has a similar overall shape to the native state.

The dimeric nature of CcdB at pH 4, as evidenced by the SEC-MALS, EPR, and AUC studies, is supported by the fluorescence spectra acquired in the presence of quencher and the Stern-Volmer plot (Fig. 1, c and d). The tryptophan in CcdB, located at the interface of two monomers, is significantly buried (Fig. S2). If the CcdB dimer dissociates to yield monomers, this tryptophan is expected to undergo a large change in its solvent accessibility. However, the fluorescence spectra and Stern-Volmer plot do not support a change in solvent accessibility of tryptophan residues at pH 4 relative to pH 7. Hence, CcdB must be dimeric at pH 4.

CcdB_4 is well folded and native-like

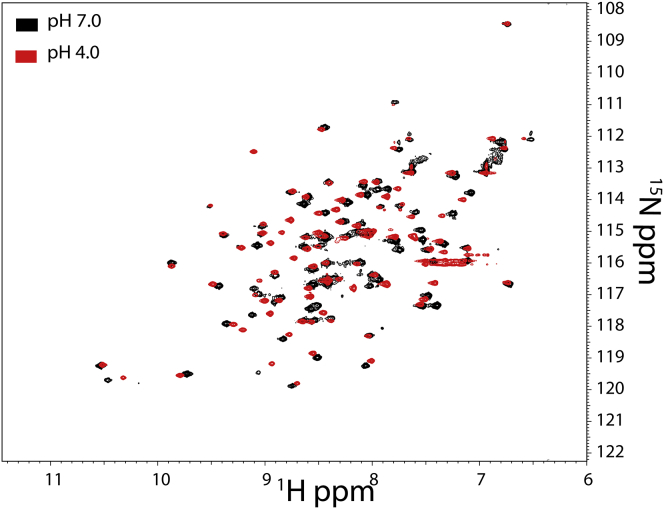

15N, 1H-edited heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of CcdB were acquired at pH 4 and pH 7. HSQC spectra of CcdB at pH 4 and pH 7 show similar dispersion range for the chemical shift of 1H and 15N. The total number of distinct peaks observed at pH 4 and pH 7 were 95 and 91, respectively, for the CcdB protein that is 101 amino acids long (Fig. 5). The results suggest that the protein remains globular in the CcdB_4 state. The 2D NMR spectra of CcdB_4 and folded CcdB at pH 7 are similar although not identical. 30% of the total peaks are identical at pH 4 and pH 7 (Fig. 5), whereas 60% show small or large shifts with change in pH (Fig. 5), indicative of structural differences between native state and CcdB_4. A small subset of the crosspeaks (∼10%) are unique at pH 4 and 7 (Fig. 5), which could be associated with larger but localized structural changes. It could be possible that these localized, larger structural changes may have facilitated ANS binding (Fig. 2). The 2D NMR spectra also support the assertion that the core of CcdB_4 is dry because penetration of water into the core of the protein would likely have caused decreased dispersion of the crosspeaks (11, 56, 57).

Figure 5.

Characterization of CcdB using NMR. 2D 15N-1H HSQC spectra of CcdB acquired at pH 4 (red color) and at pH 7 (black color) are shown. Crosspeaks are well dispersed at both pH values, suggesting that CcdB is in a globular state under both conditions. Several crosspeaks undergo a shift upon change of pH from 7 to 4, likely because of pH-induced structural changes. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although NMR can provide structural information at amino acid resolution, limited insights have been obtained about transient nonnative states using NMR because of the longer time associated with NMR measurements. Nevertheless, a few studies have reported the 2D NMR characterization of the DMG state because it populates under equilibrium under high pressure (31, 58, 59). The CcdB_4 and high-pressure ubiquitin state are compact as judged by the dispersion of crosspeaks. Similar to CcdB_4, many crosspeaks for ubiquitin at high pressure were identical to the native state, whereas many do show a small or large shift (58). Attempts were made to carry out peak assignments for CcdB using 13C, 15N-double-labeled protein; however, because of the high degeneracy of 13Cα nuclei, assignments could not be made. Future studies would involve preparation of perdeuterated samples to address this issue.

CcdB_4 not only resembles its native state at pH 7 but also appears to be functional. To evaluate its functional competence, binding studies were carried out with a peptide from the antitoxin CcdA46–72. Binding studies were also attempted with another binding partner, DNA gyrase. However, gyrase precipitates at pH 4; therefore, the binding of CcdB and gyrase could not be determined under these conditions. Temperature-induced equilibrium unfolding studies (60) were carried out with CcdB in the presence and absence of CcdA46–72. Binding of CcdA46–72 to CcdB should increase its melting temperature (Tm) (61). It was seen that CcdB has reduced thermal stability at pH 4 (apparent Tm = 59.5°C) as compared to that at pH 7 (apparent Tm = 64°C) (Fig. S7 a). The thermal stability of CcdB at pH 4 increases from 59.5 to 67°C in the presence of CcdA46–72, suggesting that CcdB_4 can bind CcdA, although the increase in Tm upon ligand binding at pH 4 is lower than that at pH 7. It should be noted that the temperature-induced equilibrium unfolding transitions monitored are not reversible and should be considered only for qualitative comparison. The binding of CcdB_4 to CcdA was also verified by monitoring the spectral shift in fluorescence emission spectra of tryptophan residues (34). The tryptophan residue of CcdA46–72 peptide undergoes a change in solvent accessibility upon binding CcdB, which should result in a blueshift in the fluorescence emission. We indeed observe that the fluorescence spectrum of the CcdA46–72-CcdB complex at pH 4 is blue shifted compared to the arithmetic sum of the individually obtained fluorescence spectra of CcdA46–72 and CcdB (Fig. S7 b). These results suggest that CcdB_4 is not only structurally similar to the native state, it is also functionally active. The fact that the CcdA-CcdB complex binds ANS (Fig. 2) suggests that CcdB at pH 4 retains exposed hydrophobic surface even after binding to CcdA peptide.

CcdB_4 has lower local stability than the native state

The preliminary NMR characterization reported above provides limited information about packing and dynamics. Hydrogen Exchange coupled to mass spectrometry (HX-MS) has been used widely for characterization of the native-state dynamics of proteins (62, 63), where studies coupled to pepsin digestion provide region-specific information (64).

Native state HX-MS studies of deuterated CcdB were carried out at pH 4 and pH 7, where exchange was carried out for various times from 10 to 50,000 s. The HX rate is determined by the opening/closing rates of the protein and by the intrinsic exchange rate, which depends on the pH of the solution and sequence of the protein (65, 66). Thus, HX results obtained at pH 4 and pH 7 cannot be compared directly. The mean intrinsic exchange rate of CcdB at pH 4 is ∼660-fold slower than its mean intrinsic exchange rate at pH 7 (65, 66). Comparison of exchange data becomes more challenging when the exchange mechanism switches from EX1 to EX2 or vice versa. Despite these caveats, it is possible to make useful inferences about dynamics by careful analysis of the HX data at pH 4 and 7.

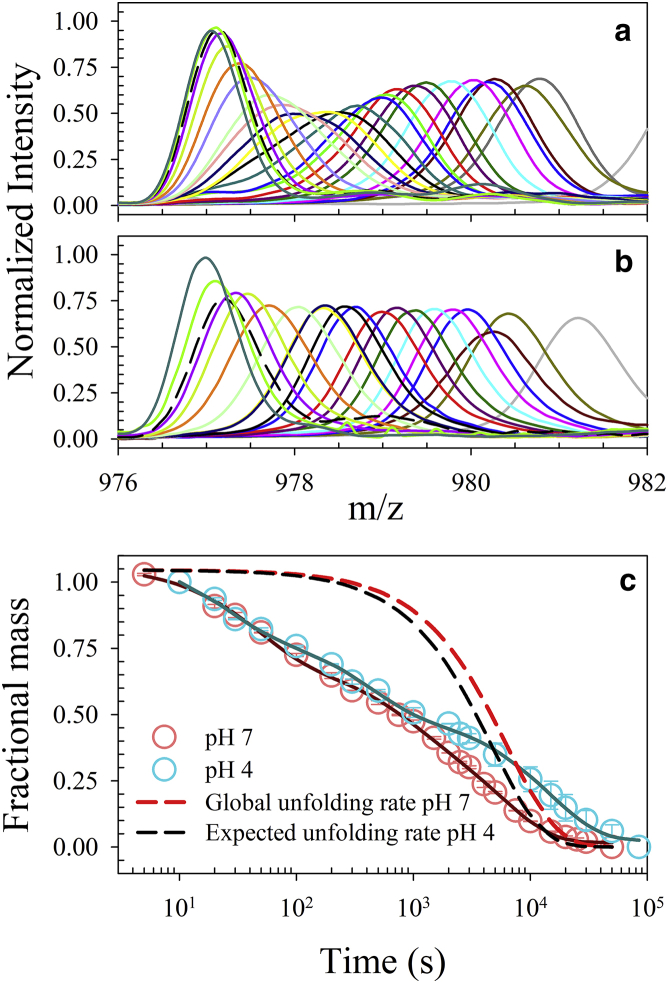

HX-MS studies of intact CcdB at pH 4 and 7 yielded mass profiles that could be described using a single Gaussian distribution (Fig. 6, a and b). Analysis was carried out by plotting observed mean mass as a function of time of exchange, assuming that exchange is occurring under the EX2 regime, although peak width analysis suggests that the slowest phase of exchange at pH 7 could be under the EXX regime (Fig. S8 b) (67, 68) because it shows significant increase in peak width as a function of time. The exchange at pH 4 does not show such increase in peak width, suggesting an EX2 exchange mechanism. The change in the peak width has been reported to reflect the mode of exchange, where the EX2 mechanism does not cause a significant change in peak width as a function of time in contrast to the EX1 mechanism (63, 64). The observed mass of CcdB as a function of time of exchange at both pH values could be satisfactorily described using a three-exponential equation (Fig. 6 c; Fig. S8 a). Obtained values of the amplitudes of all three phases of exchange at pH 4 are comparable to that of the obtained values at pH 7 (Table S2). Accounting for the change in the stability (Fig. S9) and intrinsic rate of exchange, the global unfolding phase of exchange should have comparable rates at pH 4 and pH 7 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of pH on hydrogen exchange rates of CcdB. Area-normalized mass profiles of CcdB obtained upon performing HX for various times at pH 7 and pH 4 are shown in (a) and (b), respectively. (c) Fractional protected mass of CcdB protein after various times of HX at pH 7 (pink) and pH 4 (cyan) derived from the mass profiles shown in (a) and (b). The solid lines are fit to the data using a three-exponential equation. The red dashed line represents the observed global unfolding rate at pH 7. The black dashed line represents the rate limiting exchange rate accounting for the change in stability at pH 4. Error bars represent standard errors from two independent experiments. To see this figure in color, go online.

The observed rate of the slow phase of exchange at pH 4 is marginally slower than that of the observed rate of the slow phase at pH 7 (Table S2). This difference may not be significant because it appears that exchange mechanism switches from EXX to EX2 from pH 7 to pH 4. The fast phase and medium phase show twofold faster exchange at pH 4 (Table S2). Both these phases appear to arise because of local unfolding of the protein because they are much faster than the global unfolding rate of CcdB (34). If the apparent ΔGoU of the local unfolding events were identical at both pHs, then EX2 exchange at pH 4 would have been ∼660-fold slower than at pH 7 because of the slower intrinsic rate of exchange at pH 4. Thus, the faster exchange at pH 4 suggests that local stability has decreased in CcdB_4 compared to the native state. The change in the local stability is dictated by either the increased opening rate or decreased closing rate; therefore, it can be said that CcdB_4 state appears to be far more dynamic than the native state.

Under native conditions at pH 7, after 5 s of exchange, CcdB retains ∼39 Da higher mass than the fully exchanged state, which corresponds to 39 protected amides having protection factors (69) equal to or greater than 65. Similarly, under native conditions at pH 4, CcdB has 34 amides and 29 amides whose protection factor is equal to or greater than 1 and 3, respectively. The protection factor is calculated as the ratio of the observed exchange rate to the mean intrinsic exchange rate of CcdB (65, 66, 69). The comparable numbers of protected amides at pH 4 and 7 (Fig. 6 c; Fig. S8 a) suggest that the interior of CcdB at pH 4 is shielded from water. A solvated core would exchange faster (57, 70) and is unlikely to have a similar number of protected amides as the native state. Even though CcdB_4 and the native state have a similar number of protected amides, they differ significantly in their values of protection factor. The native state has 39 amides with a protection factor equal to or greater than 65, whereas, the CcdB_4 has only 15 such amides, which corresponds to the number of protected amides at 5000 s of exchange at pH 4 (Fig. S8 a). CcdB undergoes complete exchange in less than 100,000 s at pH 4. Thus, CcdB_4 does not have any amide with a protection factor greater than 2500, whereas the native state of CcdB at pH 7 has 23 amides with a protection factor equal to or greater than 2500. Taken together, all the data suggest that CcdB_4 is considerably more dynamic than the native state of CcdB at pH 7.

Protection profile of CcdB

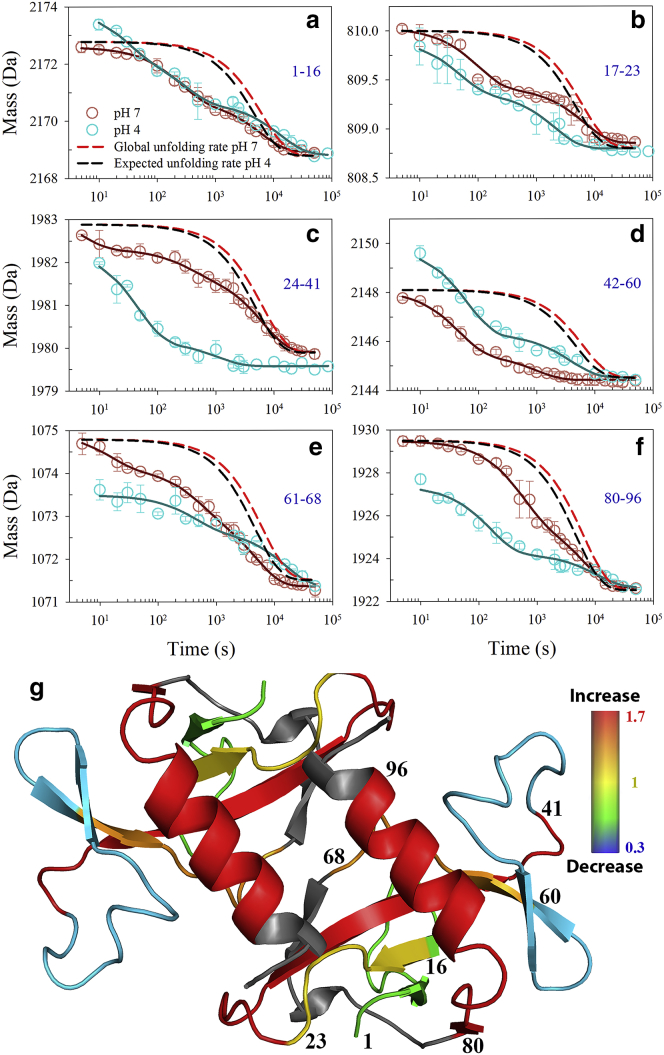

HX-MS studies coupled to pepsin digestion facilitated visualization of the dynamics in different regions of CcdB. The CcdB structure largely consists of two antiparallel β-sheets, which share a β-strand that spans the sequence segment 30–38. The sequence segment 37–62 forms a β-sheet that consists of three antiparallel β-strands. This β-sheet has low local stability as seen by HX studies. The sequence segment 42–60 that constitutes a major stretch of this β-sheet undergoes complete exchange within 3000 s (Fig. 7 d) at pH 7, which suggests that all the amides in this region exchange by local unfolding. Another β-sheet consists of five β-strands and covers sequence regions 1–36 and 63–80. This β-sheet appears to be more stable because all the sequence segments that originate from this region have at least one amide (Fig. 7) that exchanges at a rate that matches with the global unfolding rate (34). Another important structural component of CcdB structure is the single α-helix from residue 84 to 99 that forms a significant part of the interface of the homodimer. Although it contains significant solvent-exposed surface area, it also appears to be the most protected region in which most amides exchange (Fig. 7 f) at a rate that correlates with the global unfolding rate (34). When comparing exchanges kinetics for various segments at pH 4 and 7, it is clear that CcdB_4 has altered local and global fluctuations relative to pH 7 and that different regions of the structure behave quite differently, with some segments exchanging faster at pH 4 and others slower relative to corresponding rates at pH 7 (Fig. 7), suggesting that CcdB_4 is not just a native state with lowered global stability.

Figure 7.

Effect of pH on the exchange dynamics of different regions of CcdB. Hydrogen exchange rates of different regions were measured by using pepsin digestion, coupled to HX-MS. Shown are the observed masses of the sequence segments 1–16, 17–23, 24–41, 42–60, 61–68, and 80–96 obtained after different times of exchange in (a–f), respectively. Each panel shows the mass of the individual sequence segment at pH 4 (cyan circle) and pH 7 (pink circle). The solid lines in respective color represent the fit to the data using either one-, two-, or three-exponential equations. The kinetic parameters obtained upon fitting each peptide are listed in Tables S3 and S4. The red dashed lines and black dashed lines represent the rate of exchange for global unfolding at pH 7 and expected global unfolding rate at pH 4, respectively. (g) The pH-induced changes in the protection of different regions of CcdB are shown. The ratio of the protection values of different regions of CcdB at pH 4 to that at pH 7 is mapped on its structure as a heat map. The protection values were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. The regions with increased dynamics at pH 4 are marked with warmer colors, whereas those with decreased dynamics are marked with cooler colors. The uncharacterized regions are marked in gray color. The sequence segments containing β-strands colored in green, yellow, red, cyan, and orange marks the sequence segment 1–16, 17–23, 24–41, 42–60, and 61–68, respectively. The red colored segment with α-helix marks the region 80–96. The error bars represent standard error from two or more independent experiment. To see this figure in color, go online.

CcdB_4 is an expanded, nonspherical structure

Multiple observations in this report suggest that CcdB_4 is associated with a nonuniform expansion of the native state. Fluorophore anisotropy is dictated by the freedom of rotation around single bonds and by the rotational motion of the entire protein. Anisotropy measurements were performed to assess the extent of expansion of CcdB_4 compared to the native state. The steady-state anisotropy measurements show that CcdB_4 has a lower value of anisotropy than the native state (Fig. S10), consistent with increased rotational freedom of the buried tryptophan residues in CcdB and suggestive of an expanded core, which is dry but loosely packed relative to the native state. The expanded nature of CcdB_4 is also supported by the EPR data. The distance distributions observed by DEER and DQC measurements for CcdB demonstrate that the CcdB_4 is expanded and more heterogenous compared to the native state.

These observations are also supported by the HX-MS and ANS binding studies. The HX-MS studies were performed along with pepsin digestion to understand structural and thermodynamic changes in different regions of CcdB. Inspection of various regions of CcdB (Fig. 7) suggests that a few sequence segments like 24–41 and 80–96 show a dramatically enhanced exchange rate, whereas the sequence segment 17–23 shows a marginally faster exchange rate. The sequence segments 1–16 and 42–60 show comparable and slower exchange rate, respectively, at pH 4 relative to pH 7. The results suggest that some interface region of CcdB monomers undergoes a large decrease in protection at pH 4 as compared to pH 7 (Fig. 7). These observations further support the view that CcdB_4 is a polarized structure in which expansion is not happening uniformly across the structure.

This study provides useful, new, to our knowledge, insights into the structural and dynamic properties of a low-pH state. This report demonstrates using EPR and anisotropy measurements that CcdB_4 state is indeed more expanded than its native state. The structural nature of the MG was proposed to be dynamic because of disruption of core packing (13, 15). This study provides direct measurements of the increased HX dynamics of the core of CcdB_4 relative to the native state but also demonstrates that it retains binding to its cognate ligand, CcdA. Whether CcdB_4 is a MG or instead a native-like state with some partially unfolded regions and increased local dynamics is something that cannot be unambiguously determined from these studies. A locally unfolded structure would be expected to be aggregation prone; however, CcdB_4 is quite soluble and shows no evidence of enhanced aggregation propensity relative to the native CcdB at pH 7. The available data are consistent with a state that has a dry core and increased local fluctuations, including increased rotational freedom of the buried tryptophan residues. Future studies will attempt to complete NMR assignments to obtain further insights into the structure and dynamics of this state.

Author Contributions

C.B., W.E.T., R.V., and N.A. designed the research. C.B., B.S., I.W., P.B., S.P.S., and N.A. performed the research. C.B., B.S., I.W., P.B., S.P.S., R.V., and N.A. analyzed the data. C.B., W.E.T., S.P.S., R.V., and N.A. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Jayant B. Udgaonkar, Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research, Pune and the Proteomics Facility, Molecular Biophysics Unit, the Indian Institute of Science, for use of HX-MS setups. We thank Professor Borries Demeler, University of Lethbridge, for his workshop on AUC and for valuable inputs during data analysis. We thank Sanghamitra, Gajendra Dwivedi, and Akanksha Bansal from the Indian Institute of Science for assistance while running the AUC experiment. Elke Litmianski is gratefully acknowledged for technical assistance in EPR studies. We thank Bahnikana Nanda for assistance with analysis of the NMR data.

Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the University of California, San Francisco Chimera package, Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by National Institute for General Medical Sciences P41-GM103311). This work was supported by a grant to R.V. from the Department of Biotechnology (grant NO.BT/COE/34/SP15219/2015, DT.20/11/2015), government of India. We also acknowledge funding for infrastructural support from the following programs of the government of India: Department of Science and Technology/Fund for Improvement of Science and Technology, University Grants Commission Centre for Advanced Study, the Ministry of Human Resource Development, and the Department of Biotechnology/Indian Institute of Science Partnership Program. The work was also funded by the Innovation in Science Pursuit for Inspired Research Fellowship to N.A. from the Department of Science and Technology, government of India. EPR work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant P41GM103521. This work was funded by the Department of Science and Technology and Department of Biotechnology, government of India. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Editor: Daniel Raleigh.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, ten figures, and four tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(19)30062-1.

Supporting Citations

References (71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Kumar S., Nussinov R. Close-range electrostatic interactions in proteins. Chembiochem. 2002;3:604–617. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020703)3:7<604::AID-CBIC604>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pace C.N. Polar group burial contributes more to protein stability than nonpolar group burial. Biochemistry. 2001;40:310–313. doi: 10.1021/bi001574j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoemaker K.R., Kim P.S., Baldwin R.L. Tests of the helix dipole model for stabilization of alpha-helices. Nature. 1987;326:563–567. doi: 10.1038/326563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varadarajan R., Lambright D.G., Boxer S.G. Electrostatic interactions in wild-type and mutant recombinant human myoglobins. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3771–3781. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aghera N., Dasgupta I., Udgaonkar J.B. A buried ionizable residue destabilizes the native state and the transition state in the folding of monellin. Biochemistry. 2012;51:9058–9066. doi: 10.1021/bi3008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aghera N., Earanna N., Udgaonkar J.B. Equilibrium unfolding studies of monellin: the double-chain variant appears to be more stable than the single-chain variant. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2434–2444. doi: 10.1021/bi101955f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luisi D.L., Raleigh D.P. pH-dependent interactions and the stability and folding kinetics of the N-terminal domain of L9. Electrostatic interactions are only weakly formed in the transition state for folding. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:1091–1100. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato S., Raleigh D.P. pH-dependent stability and folding kinetics of a protein with an unusual alpha-beta topology: the C-terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;318:571–582. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acharya N., Mishra P., Jha S.K. Evidence for dry molten globule-like domains in the pH-induced equilibrium folding intermediate of a multidomain protein. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:173–179. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandrescu A.T., Evans P.A., Dobson C.M. Structure and dynamics of the acid-denatured molten globule state of alpha-lactalbumin: a two-dimensional NMR study. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1707–1718. doi: 10.1021/bi00058a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bom A.P., Freitas M.S., Silva J.L. The p53 core domain is a molten globule at low pH: functional implications of a partially unfolded structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:2857–2866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demarest S.J., Boice J.A., Raleigh D.P. Defining the core structure of the alpha-lactalbumin molten globule state. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:213–221. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldwin R.L., Rose G.D. Molten globules, entropy-driven conformational change and protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prajapati R.S., Indu S., Varadarajan R. Identification and thermodynamic characterization of molten globule states of periplasmic binding proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10339–10352. doi: 10.1021/bi700577m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldwin R.L., Frieden C., Rose G.D. Dry molten globule intermediates and the mechanism of protein unfolding. Proteins. 2010;78:2725–2737. doi: 10.1002/prot.22803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharyya S., Varadarajan R. Packing in molten globules and native states. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuwajima K. The molten globule state of alpha-lactalbumin. FASEB J. 1996;10:102–109. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.1.8566530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliezer D., Wright P.E. Is apomyoglobin a molten globule? Structural characterization by NMR. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;263:531–538. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chyan C.L., Wormald C., Baum J. Structure and stability of the molten globule state of Guinea-pig alpha-lactalbumin: a hydrogen exchange study. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5681–5691. doi: 10.1021/bi00072a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughson F.M., Wright P.E., Baldwin R.L. Structural characterization of a partly folded apomyoglobin intermediate. Science. 1990;249:1544–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.2218495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi T., Ikeguchi M., Sugai S. Molten globule structure of equine beta-lactoglobulin probed by hydrogen exchange. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:757–770. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nabuurs S.M., van Mierlo C.P. Interrupted hydrogen/deuterium exchange reveals the stable core of the remarkably helical molten globule of alpha-beta parallel protein flavodoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:4165–4172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.087932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolgikh D.A., Gilmanshin R.I., Ptitsyn O.B. Alpha-lactalbumin: compact state with fluctuating tertiary structure? FEBS Lett. 1981;136:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohgushi M., Wada A. ‘Molten-globule state’: a compact form of globular proteins with mobile side-chains. FEBS Lett. 1983;164:21–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reichenwallner J., Chakour M., Trommer W.E. Maltose binding protein is partially structured in its molten globule state. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2013;44:983–995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bollen Y.J., Sánchez I.E., van Mierlo C.P. Formation of on- and off-pathway intermediates in the folding kinetics of Azotobacter vinelandii apoflavodoxin. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10475–10489. doi: 10.1021/bi049545m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuwajima K. The molten globule state as a clue for understanding the folding and cooperativity of globular-protein structure. Proteins. 1989;6:87–103. doi: 10.1002/prot.340060202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoeltzli S.D., Frieden C. Stopped-flow NMR spectroscopy: real-time unfolding studies of 6-19F-tryptophan-labeled Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9318–9322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jha S.K., Marqusee S. Kinetic evidence for a two-stage mechanism of protein denaturation by guanidinium chloride. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:4856–4861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315453111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jha S.K., Udgaonkar J.B. Direct evidence for a dry molten globule intermediate during the unfolding of a small protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12289–12294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905744106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiefhaber T., Baldwin R.L. Kinetics of hydrogen bond breakage in the process of unfolding of ribonuclease A measured by pulsed hydrogen exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:2657–2661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiner A., Henklein P., Kiefhaber T. An unlocking/relocking barrier in conformational fluctuations of villin headpiece subdomain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:4955–4960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar S.S., Udgaonkar J.B., Krishnamoorthy G. Unfolding of a small protein proceeds via dry and wet globules and a solvated transition state. Biophys. J. 2013;105:2392–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baliga C., Varadarajan R., Aghera N. Homodimeric Escherichia coli toxin CcdB (controller of cell division or death B protein) folds via parallel pathways. Biochemistry. 2016;55:6019–6031. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bajaj K., Chakshusmathi G., Varadarajan R. Thermodynamic characterization of monomeric and dimeric forms of CcdB (controller of cell division or death B protein) Biochem. J. 2004;380:409–417. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kay L., Keifer P., Saarinen T. Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borbat P.P., Crepeau R.H., Freed J.H. Multifrequency two-dimensional Fourier transform ESR: an X/Ku-band spectrometer. J. Magn. Reson. 1997;127:155–167. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borbat P.P., Georgieva E.R., Freed J.H. Improved sensitivity for long-distance measurements in biomolecules: five-pulse double electron-electron resonance. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:170–175. doi: 10.1021/jz301788n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borbat P.P., Freed J.H. Dipolar spectroscopy – single-resonance methods. eMagRes. 2017;6:465–494. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banham J.E., Baker C.M., Timmel C.R. Distance measurements in the borderline region of applicability of CW EPR and DEER: a model study on a homologous series of spin-labelled peptides. J. Magn. Reson. 2008;191:202–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borbat P.P., Freed J.H. Measuring distances by pulsed dipolar ESR spectroscopy: spin-labeled histidine kinases. Methods Enzymol. 2007;423:52–116. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)23003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Georgieva E.R., Borbat P.P., Freed J.H. Mechanism of influenza A M2 transmembrane domain assembly in lipid membranes. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11757. doi: 10.1038/srep11757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiang Y.W., Borbat P.P., Freed J.H. The determination of pair distance distributions by pulsed ESR using Tikhonov regularization. J. Magn. Reson. 2005;172:279–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiang Y.W., Borbat P.P., Freed J.H. Maximum entropy: a complement to Tikhonov regularization for determination of pair distance distributions by pulsed ESR. J. Magn. Reson. 2005;177:184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganesh C., Shah A.N., Varadarajan R. Thermodynamic characterization of the reversible, two-state unfolding of maltose binding protein, a large two-domain protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5020–5028. doi: 10.1021/bi961967b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Narayanan S., Mitra G., Mandal A.K. Protein structure-function correlation in living human red blood cells probed by isotope exchange-based mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:11812–11818. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan K.P., Nguyen T.B., Madhusudhan M.S. Depth: a web server to compute depth, cavity sizes, detect potential small-molecule ligand-binding cavities and predict the pKa of ionizable residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W314–W321. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eftink M.R., Ghiron C.A. Dynamics of a protein matrix revealed by fluorescence quenching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:3290–3294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lakowicz J.R. Springer; Singapore: 2006. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlamadinger D.E., Kats D.I., Kim J.E. Quenching of tryptophanFluorescence in unfolded cytochrome c: a biophysics experiment for physical chemistry students. J. Chem. Educ. 2010;87:961–964. doi: 10.1021/ed900029c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demchenko A.P. On the nanosecond mobility in proteins. Edge excitation fluorescence red shift of protein-bound 2-(p-toluidinylnaphthalene)-6-sulfonate. Biophys. Chem. 1982;15:101–109. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(82)80022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guha S., Rawat S.S., Bhattacharyya B. Tubulin conformation and dynamics: a red edge excitation shift study. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13426–13433. doi: 10.1021/bi961251g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lakowicz J.R., Keating-Nakamoto S. Red-edge excitation of fluorescence and dynamic properties of proteins and membranes. Biochemistry. 1984;23:3013–3021. doi: 10.1021/bi00308a026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Demeler B., van Holde K.E. Sedimentation velocity analysis of highly heterogeneous systems. Anal. Biochem. 2004;335:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Holde K.E., Weischet W.O. Boundary analysis of sedimentation-velocity experiments with monodisperse and paucidisperse solutes. Biopolymers. 1978;17:1387–1403. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chamberlain A.K., Marqusee S. Molten globule unfolding monitored by hydrogen exchange in urea. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1736–1742. doi: 10.1021/bi972692i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kobashigawa Y., Demura M., Nitta K. Hydrogen exchange study of canine milk lysozyme: stabilization mechanism of the molten globule. Proteins. 2000;40:579–589. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20000901)40:4<579::aid-prot40>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu Y., Kasinath V., Wand A.J. Coupled motion in proteins revealed by pressure perturbation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8543–8550. doi: 10.1021/ja3004655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh M.I., Jain V. Identification and characterization of an inside-out folding intermediate of T4 phage sliding clamp. Biophys. J. 2017;113:1738–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niesen F.H., Berglund H., Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tripathi A., Gupta K., Varadarajan R. Molecular determinants of mutant phenotypes, inferred from saturation mutagenesis data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:2960–2975. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maity H., Lim W.K., Englander S.W. Protein hydrogen exchange mechanism: local fluctuations. Protein Sci. 2003;12:153–160. doi: 10.1110/ps.0225803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wales T.E., Engen J.R. Hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry for the analysis of protein dynamics. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2006;25:158–170. doi: 10.1002/mas.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aghera N., Udgaonkar J.B. Stepwise assembly of β-sheet structure during the folding of an SH3 domain revealed by a pulsed hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry study. Biochemistry. 2017;56:3754–3769. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bai Y., Milne J.S., Englander S.W. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins. 1993;17:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Connelly G.P., Bai Y., Englander S.W. Isotope effects in peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins. 1993;17:87–92. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weis D.D., Wales T.E., Ten Eyck L.F. Identification and characterization of EX1 kinetics in H/D exchange mass spectrometry by peak width analysis. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1498–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Witten J., Ruschak A., Jaswal S.S. Mapping protein conformational landscapes under strongly native conditions with hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:10016–10024. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b04528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bai Y., Englander J.J., Englander S.W. Thermodynamic parameters from hydrogen exchange measurements. Methods Enzymol. 1995;259:344–356. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)59051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schulman B.A., Redfield C., Kim P.S. Different subdomains are most protected from hydrogen exchange in the molten globule and native states of human alpha-lactalbumin. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;253:651–657. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Demeler B. UltraScan - A comprehensive data analysis software package for analytical ultracentrifugation experiments. In: Scott D.J., Harding S.E., Rowe A.J., editors. Analytical Ultracentrifugation: Techniques and Methods. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2005. pp. 210–230. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laue T., Shah D., Pelletier S. Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins. In: Harding S., Rowe A., Horton J., editors. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brookes E., Cao W., Demeler B. A two-dimensional spectrum analysis for sedimentation velocity experiments of mixtures with heterogeneity in molecular weight and shape. Eur. Biophys. J. 2010;39:405–414. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Demeler B., Brookes E. Monte Carlo analysis of sedimentation experiments. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2008;286:129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brookes E., Demeler B. Genetic algorithm optimization for obtaining accurate molecular weight distributions from sedimentation velocity experiments. In: Wandrey C., Cölfen H., editors. Analytical Ultracentrifugation VIII. Springer; 2006. pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Demeler B., Saber H., Hansen J.C. Identification and interpretation of complexity in sedimentation velocity boundaries. Biophys. J. 1997;72:397–407. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78680-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.