Abstract

No United States Food and Drug Administration-licensed vaccines protective against Ebola virus (EBOV) infections are currently available. EBOV vaccine candidates currently in development, as well as most currently licensed vaccines in general, require transport and storage under a continuous cold chain in order to prevent potential decreases in product efficacy. Cold chain requirements are particularly difficult to maintain in developing countries. To improve thermostability and reduce costly cold chain requirements, a subunit protein vaccine against EBOV was formulated as a glassy solid using lyophilization. Formulations of the key antigen, Ebola glycoprotein (EBOV-GP), adjuvanted with microparticulate aluminum hydroxide were prepared in liquid and lyophilized forms, and the vaccines were incubated at 40°C for 12 weeks. Aggregation and degradation of EBOV-GP were observed in liquid formulations during the 12-week incubation period, whereas changes were minimal in lyophilized formulations. Antibody responses against EBOV-GP following three intramuscular immunizations in BALB/c mice were used to determine vaccine immunogenicity. EBOV-GP formulations were equally immunogenic in liquid and lyophilized forms. After lyophilization and reconstitution, adjuvanted vaccine formulations produced anti-EBOV-GP IgG antibody responses in mice similar to those generated against corresponding adjuvanted liquid vaccine formulations. More importantly, antibody responses in mice injected with reconstituted lyophilized vaccine formulations that had been incubated at 40°C for 12 weeks prior to injection indicated that vaccine immunogenicity was fully retained after high-temperature storage, showing promise for future vaccine development efforts.

Keywords: Ebola virus, subunit protein vaccine, thermostability, lyophilization, immunogenicity, aluminum hydroxide

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a deadly viral illness that was first reported in 1976 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.1 Outbreaks of EVD have appeared sporadically over the past 50 years in multiple African countries. The largest outbreak was the 2014 to 2016 outbreak in Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia, during which a total of 28,616 cases of EVD were confirmed, resulting in 11,310 deaths.2 No licensed vaccines against EBOV infections are currently available.3 However, EBOV vaccines are the subject of research efforts worldwide (reviewed in 4, 5). Several vaccine candidates have shown promise in animal models (e.g., 6–10) and results of human clinical trials of some, mainly virally vectored, candidate EBOV vaccines have been reported.11–14

From the time of their manufacture through their transportation and storage, the temperatures to which vaccines are exposed must be controlled, often within narrow ranges, in order to maintain their efficacy. 15 For example, VSV-ZEBOV, a leading candidate EBOV vaccine developed by Merck that was tested in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, and is in current use for the ongoing outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo16 requires continuous storage between −60 and −80 °C.17 Ad26-ZEBOV, an Ebola vaccine under development by Janssen Vaccines18, was reported to be stable in a syringe at 40 °C for up to 6 hours, but drug product potency was “significantly affected” after 3 months storage at 25 °C. These “cold chain” requirements are costly and particularly difficult to maintain in low- and middle-income countries,19–21 including countries with a history of Ebola outbreaks. Additionally, logistics for potential stockpiling in preparation for future outbreaks become more complicated because of cold chain requirements. A thermostable vaccine against Ebola virus disease that could eliminate the requirement for a continuous cold chain is needed.

Lyophilization often can be used to stabilize therapeutic protein formulations. In this process, liquid solutions containing the protein and glass-forming excipients such as trehalose or sucrose first are frozen, creating a suspension of fine ice crystals within a glassy matrix of freeze-concentrated excipients. Then, the ice is removed by sublimation under vacuum, ideally leaving a solid glassy matrix in which the therapeutic protein is embedded. Molecular motions within such glassy solid matrices are highly restricted,22–24 which inhibits degradation pathways that require substantial molecular motion, such as protein aggregation. Optimally formulated, lyophilized protein formulations may be stable for extended periods of time (e.g., at least 18-24 months), even at room temperature.25

To make them sufficiently immunogenic, vaccines based on subunit protein antigens typically require addition of adjuvants such as suspensions of microparticulate aluminum hydroxide. This presents a challenge, because formulations for these vaccines must confer adequate stability to not only the protein antigen but also to any added adjuvants. Conventional lyophilization of adjuvanted protein-subunit vaccine formulations is problematic because the initial freezing step may destabilize the adjuvant suspension. Freezing of vaccine formulations that are adjuvanted with microparticulate adjuvants is particularly problematic because freezing of microparticle suspensions can induce agglomeration and result in loss of vaccine potency.26 During freezing, crystals of pure ice form, concentrating the remaining suspension of adjuvants, antigens and any added solutes such as salts and buffers, sometimes by factors of 15-20 or more.27 The combination of high concentrations of suspended adjuvant particles, high ionic strength, and potential freezing-induced pH changes can destabilize adjuvant suspensions, causing unacceptable particle agglomeration.28

We have shown that freezing-induced destabilization of aluminum hydroxide suspensions can be minimized by using a combination of formulation and lyophilization process conditions that minimize the degree of freezing-induced concentration as well as the time that the formulation spends in the freeze concentrated liquid state.28–31 First, we lyophilize from solutions that contain relatively high concentrations (e.g., 9.5 wt%) of the glass forming agent, trehalose. During freezing, trehalose maximally concentrates to about 76 wt%,32 and thus the starting concentration of 9.5% limits the possible freeze concentration for all solutes to about an 8-fold increase. Second, we use ammonium acetate as a buffer. Because ammonium acetate is volatile, it evaporates during the lyophilization process, further reducing the freeze-concentration effect on ionic strength.2 Finally, by using pre-cooled lyophilizer shelves and rapid lyophilizer shelf-cooling rates, we minimize the freeze-concentration-induced agglomeration of aluminum hydroxide microparticles by limiting the time between the points where the initial freezing event occurs and where the liquid reaches the glass transition temperature.

In this study, we apply these lyophilization formulation and processing strategies in order to minimize freeze-drying induced aluminum hydroxide agglomeration in a thermostable, aluminum hydroxide-adjuvanted subunit protein vaccine that uses insect-cell expressed EBOV-GP as an antigen. Vaccine formulations containing the antigen alone are protective in a mouse model of EBOV infection; these protective responses are increased in formulations containing adjuvants.10 To test the thermostability of the formulations, vaccines were incubated at 40°C for 12 weeks, and characterized by various biophysical techniques. Antibody responses generated against EBOV-GP in BALB/c mice after intramuscular immunizations of various EBOV-GP vaccine formulations were used to quantify the relative immunogenicity of the vaccine formulations tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The vaccine antigen, EBOV-GP, was produced at the University of Hawaii as described previously.10, 33 Aluminum hydroxide adjuvant (Alhydrogel® 2%) was obtained from Brenntag Biosector (Frederikssund, Denmark). Coomassie® Brilliant Blue G-250 was purchased from MP Biomedicals LLC (Solon, Ohio). PROTEAN® TGX™ gels from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA) were used. Anti-EBOV GP murine/human chimeric monoclonal antibody (c13C6 FR1) was purchased from IBT Bioservices (Gaithersburg, MD) and alkaline phosphatase AffiniPure goat anti-human IgG, Fcγ fragment specific was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Ammonium acetate, tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, glycine, and sodium phosphate were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Trehalose was obtained from Pfanstiehl, Inc. (Waukegan, IL). Materials from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Walthan, MA) included sodium sulfate, acrylamide, Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT), 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP), HyClone™ water for injection, and 10 × phosphate buffered saline solution (10×PBS) containing 1.37M sodium chloride, 0.027M potassium chloride and 0.119M phosphates. FIOLAX® glass vials (3 mL) were obtained from Schott (Lebanon, PA). Butyl rubber lyophilization stoppers (13 mm) were purchased from Kimble Chase Life Science and Research Products, LLC (Vineland, NJ) and aluminum seals were obtained from West Pharmaceutical Services, Inc. (Exton, PA). For animal injections, non-siliconized HSW Norm-Ject® sterile 1-mL syringes (Henke Sass Wolf, Tuttlingen, Germany) and BD™ 25G 5/8 inch sterile needles (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were used. Goldenrod™ animal lancets (Medipoint Inc., Mineola, NY) were used for submandibular bleeding and blood was collected in autoclaved 1.7 mL polypropylene tubes.

Liquid Vaccine Formulations

Vaccine formulations were composed of 0.1 mg/mL EBOV-GP in 10 mM ammonium acetate, 9.5% (w/v) trehalose at pH 7. EBOV-GP in 10 mM ammonium acetate was stored at −80°C at a stock concentration of 1.3 mg/mL. Prior to use, the EBOV-GP stock solution was thawed at room temperature, centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min to remove any insoluble protein aggregates or other particles that might have been present in the frozen and thawed stock solution. The supernatant of the centrifuged EBOV-GP stock solution was diluted in 10 mM ammonium acetate containing 12% (w/v) trehalose and a sufficient volume of 10 mM ammonium acetate to obtain a final concentration for the liquid EBOV-GP vaccine formulation of 0.1 mg/mL EBOV-GP in 10 mM ammonium acetate and 9.5% (w/v) trehalose. Some vaccine formulations were adjuvanted with microparticulate aluminum hydroxide, Alhydrogel®. In these formulations, 2% suspensions of Alhydrogel® (10 mg/mL Al), antigen stock solution containing 1.3 mg/mL EBOV-GP in 10 mM ammonium acetate, a solution of 12% trehalose in 10 mM ammonium acetate, and sufficient 10 mM ammonium acetate were added to 1.6 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes to yield final formulations containing 0.1 mg/mL EBOV-GP, 0.5 mg/mL Al and 9.5% trehalose in 9.5 mM ammonium acetate. These formulations were rotated end-over-end for 1 hour at 4°C to allow EBOV-GP to adsorb to the aluminum hydroxide particles. Solutions were prepared with sterile water for injection, containers used to make the buffers and protein formulations were sterilized by autoclave or purchased sterile. Alhydrogel® 2% was purchased sterile and aliquots were removed from the bottle using aseptic techniques. For vaccine formulations that were not lyophilized, 1 mL of liquid vaccine formulations were aliquoted into 3 mL glass vials, stoppered, and sealed with aluminum caps. Prior to their administration, these liquid vaccine formulations were stored at 4°C, or incubated at 40°C for 12 weeks.

Lyophilization and Reconstitution of Vaccine Formulations

An FTS Systems LyoStar lyophilizer (Warminster, PA) was used for freeze-drying of vaccine formulations. The formulation excipients and lyophilization cycle used for the EBOV-GP formulations were essentially identical to those used by Hassett et al.29–31Lyophilizer shelves were pre-cooled to −10°C. Three mL FIOLAX® glass vials (Schott, Lebanon, PA) were filled with one mL of the various liquid vaccine formulations and vial stoppers were placed halfway onto vials. Vials were then placed on a pre-cooled shelf in lyophilizer sample chamber. To minimize variation in heat transfer to individual vials due to radiation and edge vial effects, sample vials containing test vaccine formulations were surrounded by vials that were filled with water.34 During the freezing stage of the lyophilization cycle, the lyophilizer shelf temperature was decreased at a rate of 0.5°C/min to −40°C and then held at−40°C for 1 hour to ensure that vial contents were completely frozen. The lyophilizer pressure was decreased to 8 Pa to initiate primary drying, and shelf temperature was increased to − 20°C at a rate of 1°C/min and then held for 20 hours. After the 20 hours of the primary drying cycle, pressure continued to be controlled at 8 Pa while secondary drying was initiated by increasing the lyophilizer shelf temperature to 0°C at a rate of 0.2°C/min, followed by an increase to 30°C at 0.5°C/min, where the temperature was held for 5 hours. At the end of the cycle, the lyophilizer was back-filled with filtered nitrogen until atmospheric pressure was reached, and the vials were sealed automatically while still in the nitrogen filled lyophilization chamber by manually collapsing the lyophilizer shelves to move the vial stoppers from the halfway position to their fully inserted, sealed position. After the sealed vials were removed from the lyophilizer, the vial stoppers were secured with aluminum caps. Some of the lyophilized vaccines were kept at 40°C for 12 weeks; lyophilized vaccine formulations that were not subjected to high-temperature storage were kept at −80°C until use. Prior to their administration to mice, the lyophilized vaccine formulations were reconstituted with the amount of water for injection (WFI) required to obtain a total volume of 1.0 mL. Reconstituted vaccine formulations were gently mixed and held on bench for a minimum of 30 minutes before testing. An additional vaccine formulation consisted of a reconstituted lyophilized vaccine formulation where aluminum hydroxide microparticles were added after lyophilization and reconstitution. For this formulation, water for injection was added to the lyophilized formulation followed by addition a suspension of aluminum hydroxide to yield a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL aluminum hydroxide in a total volume of 1.0 mL. Subsequently, the same protocol was followed as used for the liquid formulations containing aluminum hydroxide where the formulation was transferred from vials to 1.6 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes and rotated end-over-end for 1 hour at 4°C to allow EBOV-GP to adsorb to the aluminum hydroxide particles before testing was conducted.

SDS-PAGE, Coomassie Staining, and Western Blotting

After reconstitution of lyophilized vaccines, vaccines were characterized using SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining as well as by western blotting with the conformation-sensitive anti-EBOV-GP antibody c13C6.35 EBOV-GP in adjuvanted samples binds tightly to aluminum hydroxide. Thus, aluminum hydroxide -containing formulations were pretreated so that the bound proteins could be extracted into the solution phase. An extraction protocol36 reported earlier using the combination of phosphate, citrate, and SDS was simplified here. Briefly, 50 μL of adjuvanted vaccine samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min, and the supernatants, which did not contain any appreciable amount of protein (as determined by SEC-HPLC analysis), were discarded. To the pellet, 10 uL of 2×SDS loading buffer and the same volume of 10×PBS were added in the presence or absence of 100 mM DTT for reducing and non-reducing PAGE, respectively. The resulting suspensions were incubated for 10 min at 70 °C, and supernatants were collected after centrifuging for 5 min at 12,000 g. For the quantitative recovery of the extracted proteins, pellets were briefly washed with 5 μL of 1:1 mixture of 2×SDS loading buffer and 10×PBS pre-heated to 70 °C. Pooled extracts and washes were used for electrophoretic analyses.

Non-reduced samples containing 0.75 micrograms EBOV-GP and reduced samples containing 0.75 micrograms EBOV-GP and 100 mM DTT were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 4 – 20% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ gels in Tris-glycine running buffer. One gel was stained with Coomassie® Brilliant Blue G-250. A second gel was transferred on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for western blotting. For western blotting, the primary antibody used was anti-EBOV GP murine/human chimeric monoclonal antibody (c13C6 FR1) and the secondary antibody used was an alkaline phosphatase goat anti-human IgG. An alkaline developer containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP) and Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) was used to develop the blot.

Size-Exclusion High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (SE-HPLC)

Size-exclusion HPLC was used to monitor monomeric and soluble high and low molecular weight species in EBOV-GP samples. For formulations containing aluminum hydroxide, the amount of EBOV-GP remaining in solution and amount of EBOV-GP adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide were quantified by size-exclusion HPLC and mass balance as described previously.37 Sample aliquots for SE-HPLC were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant of each samples was passed through two TSKgel G3000SWXL columns in series (TOSOH Biosciences, Montgomeryville, PA) on an Agilent 1100 series system (Santa Clara, CA) HPLC instrument. The absorbance of the eluent was monitored at 280 nm using the Agilent ChemStation software. The mobile phase of 100 mM sodium sulfate, 100 mM sodium phosphate, and 0.05% (w/v) sodium azide at pH 6.7 was passed through the system at 0.6 mL/min. Peak areas in chromatograms were calculated using GRAMS/AI software version 9.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Carlsbad, CA).

Intrinsic Fluorescence Quenching of Adsorbed EBOV-GP

Tertiary structure changes in EBOV-GP in vaccine formulations with or without aluminum hydroxide were monitored using intrinsic fluorescence quenching of protein tryptophan residues using acrylamide. An SLM Aminco fluorimeter (SLM Instruments, Urbana, Illinois) was used in front-face mode to monitor fluorescence intensity as described previously in Gerhardt et al.38 Samples and controls included native EBOV-GP, EBOV-GP unfolded in 8 M urea, and non-adjuvanted or aluminum hydroxide-containing vaccine formulations after lyophilization and reconstitution. Data were graphed in the form of a Stern-Volmer plot and Stern-Volmer constants (KSV), which indicate the relative accessibility of solvent to tryptophan residues, were obtained from the initial slope of the Stern-Volmer plots.

Particle Analysis (FlowCAM)

Particle concentrations and number-weighted particle size distributions in the micron size range were obtained using a flow microscopy digital imaging technique, FlowCAM® (Fluid Imaging Technologies, Scarborough, ME), as previously described.39 Lyophilized formulations were reconstituted prior to analysis and were measured in triplicate.

Immunogenicity Testing in Animals

Animal experiments in protocol 2318-4DEC2018 were approved by the University of Colorado Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult female BALB/c mice greater than 6 weeks of age were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Up to five mice were housed in each sterile, air-filtered cage with food and water available ad libitum. Mice were allowed to acclimate for 10 days before the start of the study.

Groups of eight mice were injected with the various formulations of liquid and reconstituted lyophilized vaccines. Another group of mice was injected with a reconstituted lyophilized vaccine formulation where aluminum hydroxide was added after lyophilization in the diluent and compared to the formulation where aluminum hydroxide was added before lyophilization. Additionally, liquid or lyophilized vaccine formulations that had been incubated at 40°C for 12 weeks were administered to groups of mice. Intramuscular injections of 10 μg EBOV-GP were administered on Day 0, 21, and 42. A total of 100 μL of the EBOV-GP formulation was administered to each mouse as 50 μL intramuscular injections in each thigh. Blood was collected using submandibular bleeding on Days 0, 14, 35, 56. Blood samples were collected in sterile microcentrifuge tubes and placed on ice. Subsequently, samples were centrifuged at 2,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Serum was collected and stored in aliquots at −80°C until further analysis.

Characterization of Antibody Responses

Antibody responses against EBOV-GP in mice were determined using a Luminex Based Microsphere Immunoassay (MIA). The coupling of microspheres with EBOV GP was performed as described previously40. Internally dyed, carboxylated, magnetic microspheres (MagPlexTM-C) were obtained from Luminex Corporation (Austin, TX, USA). A two-step carbodiimide process recommended by Luminex was used to link 10 μg of purified EBOV GP to the surface of 1.25×106 microspheres. The antigen-conjugated microspheres were stored in 250 μL of PBN buffer (PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin Fraction V, OmniPur, and 0.05% Ultra sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 4°C. Microspheres dyed with spectrally different fluorophores were also coupled with untransformed S2 cell culture supernatant (to control for potential co-purified insect cell derived proteins), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and PBS for controls.

Microspheres coupled with EBOV-GP, untransformed S2 supernatant, BSA and PBS were pooled in PBS-1% BSA (PBS-BSA) at a dilution of 1:200. Fifty μL of the coupled microsphere suspension were added to each well of black-sided 96-well plates. Serum samples were diluted 1:100 in PBS-BSA and 50 μL were added to the microspheres in duplicate and incubated for 30 min on a plate shaker set at 700 rpm in the dark at room temperature. The plates were then washed twice with 200 μL of PBS-BSA using a magnetic plate separator (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA). Fifty μL of red-phycoerythrin (R-PE) conjugated F(ab’)2 fragment goat anti-mouse IgG, Fcγ fragment specific (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) were added at 1 μg/mL to the plates and incubated another 45 min. The plates were washed twice as above and microspheres were then re-suspended in 100 μL of sheath fluid and analyzed on the Luminex 100 (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX). Data acquisition detecting the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was set to 50 beads per spectral region. Antigen-coupled beads were recognized and quantified based on their spectral signature and signal intensity, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

To determine statistical differences in MFI values between experimental groups, nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests were performed using SigmaPlot® 12.2 software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, California). The sample size was eight mice in each experimental group. Differences between experimental groups were considered statistically significant when p values were less than a value of 0.05.

RESULTS

Characterization of Vaccine Formulations

Figure 1 shows SDS-PAGE of EBOV-GP vaccine formulations with Coomassie staining (left) and western blotting using a conformation-dependent anti-EBOV-GP mAb (right). The EBOV-GP liquid formulation is shown in lane 1 and shows a main band at a size of approximately 95 kDa , corresponding to monomeric GP, as well as smaller bands appearing at lower molecular weights. EBOV-GP is heavily glycosylated41, and thus the band positions do not correspond exactly to the molecular weights of the band marker proteins. Under reducing conditions the main band shifted to lower molecular weight, consistent with dissociation of the ~20kDa GP2 subunit from GP1. Under non-reducing conditions, all of the bands reacted with the anti-EBOV GP antibody c13C6 FR1; this reactivity was completely eliminated under reducing conditions. As expected, the anti-EBOV-GP mAb did not detect any EBOV-GP in any vaccine formulation analyzed under reducing conditions as these conditions dissociate the disulfide-linked42 GP1 and GP2 subunits. While GP1 can be seen under all tested conditions and in a consistent quantity allowing assessment of antigen recovery, GP2 is not seen on PAGE analysis since it appears as three different glycoforms in approximately equal amount, reducing each band below the limit of detection for Coomassie-staining. Under non-reducing conditions, no observable changes in these bands were detected between the liquid EBOV-GP formulation and the lyophilized and reconstituted EBOV-GP formulation, or between the EBOV-GP lyophilized and reconstituted formulation and lyophilized EBOV-GP formulations that were stored for 12 weeks at 40 °C. After incubation of the liquid EBOV-GP formulations for 12 weeks at 40 °C, significant losses of the monomer band were observed, irrespective of the presence or absence of aluminum hydroxide microparticles. The disappearance of EBOV-GP bands on the gels could be attributed to aggregation of the protein, which could also be observed visually. Incubation with SDS did not dissolve the aggregates, and even in the presence of DTT the amount of EBOV–GP that could enter the gel was very low.

Figure 1.

Analysis of liquid (LIQ E-GP) and reconstituted lyophilized (Lyo E-GP) vaccine formulations by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (left) and western blot with conformationally-dependent anti-EBOV-GP mAb (right). Aluminum hydroxide -containing formulations (denoted with “+ alum”) were pretreated with 2×SDS 10×PBS solution to desorb protein from aluminum hydroxide microparticles. Samples were analyzed before and after 12 weeks of incubation at 40°C.

Figure 2 shows size-exclusion chromatograms of liquid vaccine formulations (Fig. 2a) and reconstituted lyophilized vaccine formulations (Fig. 2b). The chromatogram of the liquid EBOV-GP formulation consists of a peak eluting at 25 minutes labeled “Peak A” that was assumed to correspond to monomeric EBOV-GP, a peak eluting at 21 minutes labeled “Peak B” that was assumed to correspond to trimeric EBOV, and additional high molecular weight (HMW) and low molecular weight (LMW) species peaks that eluted before and after the main peaks, respectively. The chromatogram for the liquid EBOV-GP formulation that has been incubated at 40 °C for 12 weeks showed that Peak A was greatly reduced, Peak B was almost completely lost and increased levels of HMW species and LMW species were detected (Fig 2a). After 12 weeks of incubation at 40 °C, the lyophilized EBOV-GP formulations (Fig 2b) exhibited smaller losses of Peak A and Peak B and smaller increases in HMW species compared to the incubated liquid formulation.

Figure 2.

Size-exclusion chromatograms of (a) liquid vaccine formulations that were freshly prepared (black solid line) or incubated for 12 weeks at 40C (gray dashed line) and (b) lyophilized and reconstituted vaccine formulations that were not incubated (light gray solid line) or incubated for 12 weeks at 40C (dark gray dashed line). The absorbance of the eluent was monitored at 280 nm.

No soluble protein was detected in chromatograms of formulations containing aluminum hydroxide, suggesting that essentially all EBOV-GP was adsorbed to the particles (data not shown). Insoluble protein and aluminum hydroxide particles in formulations were monitored using FlowCAM®. The mean diameters of aluminum hydroxide particles in the liquid EBOV-GP formulations and the lyophilized and reconstituted EBOV-GP formulations were 2.7 ± 0.1 μm and 4.7 ± 0.1 μm, respectively. This suggests that some agglomeration of aluminum hydroxide occurred during the lyophilization and/or reconstitution process. However, the mean diameter after lyophilization and reconstitution was well below the reported 10 μm upper limit for optimal adjuvant activity.43

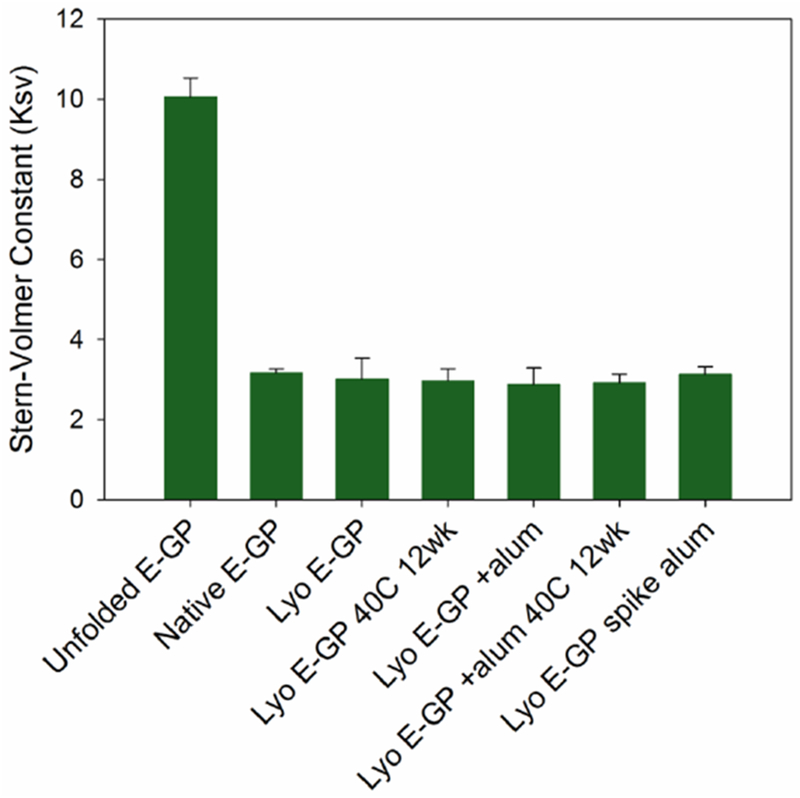

Changes in EBOV-GP tertiary structure were monitored using intrinsic fluorescence quenching of tryptophan residues within the protein. Figure 3 shows Stern-Volmer constants for EBOV-GP in lyophilized, reconstituted vaccine formulations. As expected, the Stern-Vomer constant of unfolded EBOV-GP was significantly higher than that of native EBOV-GP. After lyophilization and reconstitution of EBOV-GP formulations, the protein retained near-native tertiary structure irrespective of the presence or absence of aluminum hydroxide microparticles. Furthermore, near-native structure was retained in lyophilized vaccine formulations after 12 weeks of incubation at 40°C.

Figure 3.

Stern-Volmer constants for EBOV-GP in various formulations, including EBOV-GP unfolded in 8M urea (Unfolded E-GP), EBOV-GP in liquid formulations prior to incubation or lyophilization (Native E-GP), lyophilized and immediately reconstituted EBOV-GP (Lyo E-GP), lyophilized EBOV-GP incubated at 40 °C for 12 weeks prior to reconstitution (Lyo E-GP 40C12 wk), lyophilized and reconstituted EBOV-GP formulation containing aluminum hydroxide (Lyo E-GP + alum), lyophilized EBOV-GP containing aluminum hydroxide incubated at 40 °C for 12 weeks prior to reconstitution (Lyo E-GP + alum 40C 12 wk), and lyophilized EBOV-GP formulations where aluminum hydroxide was spiked in after reconstitution (Lyo E-GP spike alum). After 12 weeks at 40 °C, EBOV-GP in liquid samples was too aggregated to permit reliable determination of Stern-Volmer constants (data not shown).

Antibody Responses against Liquid and Lyophilized EBOV-GP Vaccine Formulations

Figure 4 shows antibody responses against EBOV-GP for mice injected with liquid or lyophilized vaccine formulations that had not been incubated at 40 °C. Liquid and lyophilized vaccine formulations prepared without aluminum hydroxide produced similar anti-EBOV-GP IgG antibody responses. Likewise, aluminum hydroxide-containing liquid and lyophilized vaccine formulations produced similar anti-EBOV-GP IgG antibody responses. Antibody responses measured after the first dose were slightly above the baseline cutoff value for formulations that contained aluminum hydroxide, but were at baseline levels in formulations without aluminum hydroxide. However, first-dose antibody responses to a given formulation were not discernably affected by storage at 40° C (data not shown). Mice administered aluminum hydroxide-containing vaccine formulations exhibited stronger antibody responses following doses 2 and 3 (p < 0.001, p < 0.001) than mice administered vaccine formulations without aluminum hydroxide. Antibody responses to lyophilized EBOV-GP formulations where aluminum hydroxide was added after reconstitution were similar to responses to EBOV-GP formulations where aluminum hydroxide was added prior to the lyophilization step.

Figure 4.

Anti-EBOV-GP IgG antibody responses to liquid (LIQ-E-GP) and lyophilized and reconstituted (Lyo-E-GP) vaccines measured as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Murine serum samples were analyzed after two doses on Day 35 (open diamonds) and after three doses on Day 56 (closed diamonds). Each data point represents the MFI value obtained from serum of an individual mouse. Although addition of aluminum hydroxide (points denoted with “+ alum”) to both liquid and lyophilized formulations greatly increased responses to the vaccine, responses were equivalent whether the aluminum hydroxide was added prior to lyophilization (LYO E-GP) or after lyophilization and reconstitution (LYO E-GP spike alum).

Incubation at 40°C for 12 weeks did not affect the immunogenicity of the lyophilized vaccines, irrespective of their aluminum hydroxide content (Figure 5). Immunogenicity of the liquid vaccine formulations were similarly insensitive to 12 weeks of incubation at 40°C; responses measured after the second dose were slightly but not significantly lower (p = 0.08) for the incubated samples, but were indistinguishable (p=0.9) after three doses.

Figure 5.

Effect of twelve weeks of incubation at 40°C on anti-EBOV-GP IgG antibody MFI responses to EBOV vaccines. Serum samples were analyzed post dose two at Day 35 (open diamonds) and post dose three at Day 56 (closed diamonds). Vaccine formulations were prepared in the presence (a) and absence (b) of aluminum hydroxide. Each data point represents the IgG MFI value obtained from serum of an individual mouse. Due to an experimental mishap, data from only four mice were available in the group for the lyophilized, aluminum hydroxide-containing samples incubated at 40°C for 12 weeks.

DISCUSSION

Mice injected with the liquid form of the EBOV-GP vaccine formulation and mice injected with the reconstituted lyophilized form of the EBOV-GP vaccine formulation produced similar IgG antibody responses against EBOV-GP, showing that the liquid and lyophilized formulations were equally immunogenic. Additionally, antibody responses in mice administered the lyophilized vaccine formulation that had been incubated at 40°C for 12 weeks prior to reconstitution and injection were similar to responses in mice administered the non-incubated lyophilized vaccine formulation. Therefore, immunogenicity of lyophilized EBOV-GP vaccine formulations was not diminished after storage for 12 weeks at a temperature that is near the maximum ambient temperature in regions where Ebola outbreaks occur.

After incubation for 12 weeks at 40°C, the aggregation state of EBOV-GP was altered in liquid formulations, whereas only minimal changes were seen in lyophilized formulations. We had thus expected a corresponding loss in immunogenicity following 40°C incubation of the liquid formulations. However, incubating the aluminum hydroxide-adjuvanted liquid EBOV-GP formulation for 12 weeks at 40°C did not result in decreased antibody responses against EBOV-GP. Western blotting with the conformation-sensitive c13C6 antibody and SE-HPLC showed changes in the assembly state of EBOV-GP in this formulation, but antibody responses were insensitive to this physical degradation. The conformation-sensitive c13C6 antibody also bound to the degradation products, and thus epitopes assumed to be key for proper immunogenicity appear to have been retained even in the degraded protein fractions. This is consistent with the fluorescence quenching results, which suggested that the EBOV-GP retained near-native tertiary structure. Anti-EBOV-GP IgG MFI values following dose two at day 35 and following dose three at day 56 were similar for mice injected with lyophilized vaccine formulations containing aluminum hydroxide. One explanation for these results could be that, at the 10 μg dose used for the study, immune responses reached saturation and thus only a fraction of the initially-present EBOV-GP was required to yield significant antibody responses.

As expected, EBOV-GP vaccine formulations that contained the common vaccine adjuvant aluminum hydroxide were more immunogenic than EBOV-GP vaccine formulations without adjuvant. Freezing typically causes aggregation of aluminum hydroxide particles yielding particles of up to 10 to 100 μm in diameter in vaccine formulations. The effect of these freezing-induced increases in adjuvant particle size remains controversial. Freezing can lead to losses in vaccine efficacy.26, 28, 44, 45 One study suggested that the agglomeration of aluminum salt adjuvant particles during freezing and drying is the cause of this freezing-induced loss of immunogenicity44, but in a subsequent study that examined freeze-thawing stability of alum-adjuvanted vaccines, immune responses were not altered as a result of freezing-induced changes in adjuvant particle size distributions46. Irrespective of whether freezing-induced agglomeration of adjuvant alters immunogenicity, the presence of large aggregates within vaccine formulations would not likely be pharmaceutically acceptable.

In the present study, particles with a mean diameter of less than 5 μm were observed after lyophilization and reconstitution, likely because the presence of 9.5% trehalose within the formulation inhibited agglomeration. These results were in agreement with Clausi et al.8, who showed that high concentrations of amorphous forming excipients minimized aggregation of aluminum hydroxide during the freeze-drying process. Furthermore, our study found that antibody responses in mice injected with a reconstituted lyophilized vaccine formulation where aluminum hydroxide was added after lyophilization in the diluent were equivalent to antibody responses in mice injected with the formulation where aluminum hydroxide was added before lyophilization. This suggests that even though the aluminum hydroxide -adjuvanted EBOV vaccine formulations were subjected to freezing as part of the lyophilization cycle, any freezing-induced changes in the aluminum hydroxide suspensions were minor and did not affect vaccine immunogenicity.

The development of stable, lyophilized Ebola vaccine formulations may greatly reduce cold-chain requirements. Even though immune responses were equivalent for the liquid and lyophilized formulations that we tested, the physical degradation of the EBOV-GP protein that was observed in the liquid formulations following incubation at 40°C likely would limit acceptability of the liquid formulation in the absence of strict cold chain requirements, motivating the use of lyophilized preparations. It should be noted, however, that lyophilized formulations present additional challenges, such as the requirements for in-field reconstitution and the need for separate diluent vials which require additional storage space, or lyophilization within dual-cartridge syringes, which add cost.

CONCLUSIONS

Protein assembly state was significantly degraded in liquid EBOV-GP formulations after incubation at high temperature, whereas changes in protein assembly state were minimal in lyophilized formulations. Our findings show that lyophilization did not decrease immunogenicity of the vaccine in mice compared to liquid EBOV-GP formulations. Also, antibody responses in mice injected with reconstituted lyophilized vaccine formulations that had been incubated at high temperature for 12 weeks prior to injection were similar to responses in mice injected with reconstituted lyophilized vaccines that had not been incubated at elevated temperature, indicating no loss in vaccine immunogenicity after high-temperature storage. Lyophilized EBOV-GP vaccine formulations were thermostable and potentially could eliminate the need for a cold-chain during distribution and storage. Promising results led to continued work on thermostabilization of EBOV GP and other filovirus vaccine candidates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this project was provided in part by a grant from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI119185) and through corporate funds of Soligenix, Inc. TJK was also supported by the research grant of Dongguk University. We thank Oreola Donini of Soligenix, Inc. for assistance in project coordination.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maganga GD; Kapetshi J; Berthet N; Ilunga BK; Kabange F; Kingebeni PM; Mondonge V; Muyembe JJT; Bertherat E; Briand S; Cabore J; Epelboin A; Formenty P; Kobinger G; Gonzalez-Angulo L; Labouba I; Manuguerra JC; Okwo-Bele JM; Dye C; Leroy EM, Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 371 (22), 2083–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC Outbreaks Chronology: Ebola Virus Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/chronology.html (accessed March 8, 2018).

- 3.Bausch DG, One Step Closer to an Ebola Virus Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 376 (10), 984–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaye D, US Invests $170 Million in Late-Stage Ebola Vaccines, Drugs. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018, 66 (1), II–II. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong G; Mendoza EJ; Plummer FA; Gao GF; Kobinger GP; Qiu XG, From bench to almost bedside: the long road to a licensed Ebola virus vaccine. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 2018, 18 (2), 159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matassov D; Mire CE; Latham T; Geisbert JB; Xu R; Ota-Setlik A; Agans KN; Kobs DJ; Wendling MQS; Burnaugh A; Rudge TL; Sabourin CL; Egan MA; Clarke DK; Geisbert TW; Eldridge JH, Single-Dose Trivalent VesiculoVax Vaccine Protects Macaques from Lethal Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus Challenge. Journal of Virology 2018, 92 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shuai L; Wang XJ; Wen ZY; Ge JY; Wang JL; Zhao DD; Bu ZG, Genetically modified rabies virus-vectored Ebola virus disease vaccines are safe and induce efficacious immune responses in mice and dogs. Antiviral Research 2017, 146, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domi A; Feldmann F; Basu R; McCurley N; Shifflett K; Emanuel J; Hellerstein MS; Guirakhoo F; Orlandi C; Flinko R; Lewis GK; Hanley PW; Feldmann H; Robinson HL; Marzi A, A Single Dose of Modified Vaccinia Ankara expressing Ebola Virus Like Particles Protects Nonhuman Primates from Lethal Ebola Virus Challenge. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer M; Huang E; Yuzhakov O; Ramanathan P; Ciaramella G; Bukreyev A, Modified mRNA-Based Vaccines Elicit Robust Immune Responses and Protect Guinea Pigs From Ebola Virus Disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2018, 217 (3), 451–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehrer AT; Wong TS; Lieberman MM; Humphreys T; Clements DE; Bakken RR; Hart MK; Pratt WD; Dye JM, Recombinant proteins of Zaire ebolavirus induce potent humoral and cellular immune responses and protect against live virus infection in mice. Vaccine 2018, 36 (22), 3090–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy SB; Bolay F; Kieh M; Grandits G; Badio M; Ballou R; Eckes R; Feinberg M; Follmann D; Grund B; Gupta S; Hensley L; Higgs E; Janosko K; Johnson M; Kateh F; Logue J; Marchand J; Monath T; Nason M; Nyenswah T; Roman F; Stavale E; Wolfson J; Neaton JD; Lane HC; Grp PIS, Phase 2 Placebo-Controlled Trial of Two Vaccines to Prevent Ebola in Liberia. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377 (15), 1438–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agnandji ST; Fernandes JF; Bache EB; Obiang RM; Brosnahan JS; Kabwende L; Pitzinger P; Staarink P; Massinga-Loembe M; Krahling V; Biedenkopf N; Fehling SK; Strecker T; Clark DJ; Staines HM; Hooper JW; Silvera P; Moorthy V; Kieny MP; Adegnika AA; Grobusch MP; Becker S; Ramharter M; Mordmuller B; Lell B; Krishna S; Kremsner PG; Consortium V, Safety and immunogenicity of rVSV Delta G-ZEBOV-GP Ebola vaccine in adults and children in Lambarene A, Gabon: A phase I randomised trial. Plos Medicine 2017, 14 (10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coller BAG; Blue J; Das R; Dubey S; Finelli L; Gupta S; Helmond F; Grant-Klein RJ; Liu K; Simon J; Troth S; VanRheenen S; Waterbury J; Wivel A; Wolf J; Heppner DG; Kemp T; Nichols R; Monath TP, Clinical development of a recombinant Ebola vaccine in the midst of an unprecedented epidemic. Vaccine 2017, 35 (35), 4465–4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ElSherif MS; Brown C; MacKinnon-Cameron D; Li L; Racine T; Alimonti J; Rudge TL; Sabourin C; Silvera P; Hooper JW; Kwilas SA; Kilgore N; Badorrek C; Ramsey WJ; Heppner DG; Kemp T; Monath TP; Nowak T; McNeil SA; Langley JM; Halperin SA; Canadian Immunization, R., Assessing the safety and immunogenicity of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus Ebola vaccine in healthy adults: a randomized clinical trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2017, 189 (24), E819–E827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumru OS; Joshi SB; Smith DE; Middaugh CR; Prusik T; Volkin DB, Vaccine instability in the cold chain: mechanisms, analysis and formulation strategies. Biologicals 2014, 42 (5), 237–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaye D, Congo Starts Using Experimental Ebola Treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018, 67 (10), I–I. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friend M; Stone S; Ieee, Challenging Requirements in Resource Challenged hnvironment on a Time Challenged Schedule: A technical solution to support the cold chain for the VSV-Zebov (Merck) Ebola vaccine in Sierra Leone and Guinea. Proceedings of the Fifth Ieee Global Humanitarian Technology Conference Ghtc 2015 2015, 372–376. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capelle MAH; Babich L; van Deventer-Troost JPE; Salerno D; Krijgsman K; Dirmeier U; Raaby B; Adriaansen J, Stability and suitability for storage and distribution of Ad26.ZEBOV/MVABN (R)-Filo heterologous prime-boost Ebola vaccine. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2018, 129, 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin A; Wang SA; Levin C; Tsu V; Hutubessy R, Costs of introducing and delivering HPV vaccines in low and lower middle income countries: inputs for GAVI policy on introduction grant support to countries. PLoS One 2014, 9 (6), e101114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristensen D; Chen D; Cummings R, Vaccine stabilization: Research, commercialization, and potential impact. Vaccine 2011, 29 (41), 7122–7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kristensen DD; Lorenson T; Bartholomew K; Villadiego S, Can thermostable vaccines help address cold-chain challenges? Results from stakeholder interviews in six low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine 2016, 34 (7), 899–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Champion D; Hervet H; Blond G; LeMeste M; Simatos D, Translational diffusion in sucrose solutions in the vicinity of their glass transition temperature. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1997, 101 (50), 10674–10679. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pikal MJ; Rigsbee D; Roy ML; Galreath D; Kovach KJ; Wang B; Carpenter JF; Cicerone MT, Solid state chemistry of proteins: II. The correlation of storage stability of freeze-dried human growth hormone (hGH) with structure and dynamics in the glassy solid. J Pharm Sci 2008, 97 (12), 5106–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang BQ; Tchessalov S; Cicerone MT; Warne NW; Pikal MJ, Impact of Sucrose Level on Storage Stability of Proteins in Freeze-Dried Solids: II. Correlation of Aggregation Rate with Protein Structure and Molecular Mobility. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2009, 98 (9), 3145–3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpenter JF; Chang BS; Garzon-Rodriguez W; Randolph TW, Rational design of stable lyophilized protein formulations: theory and practice. Pharm Biotechnol 2002, 13, 109–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zapata MI; Feldkamp JR; Peck GE; White JL; Hem SL, Mechanism of freeze-thaw instability of aluminum hydroxycarbonate and magnesium hydroxide gels. J Pharm Sci 1984, 73 (1), 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhatnagar BS; Pikal MJ; Bogner RH, Study of the individual contributions of ice formation and freeze-concentration on isothermal stability of lactate dehydrogenase during freezing. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2008, 97 (2), 798–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clausi AL; Merkley SA; Carpenter JF; Randolph TW, Inhibition of aggregation of aluminum hydroxide adjuvant during freezing and drying. Journal Of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2008, 97 (6), 2051–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassett KJ; Vance DJ; Jain NK; Sahni N; Rabia LA; Cousins MC; Joshi S; Volkin DB; Middaugh CR; Mantis NJ; Carpenter JF; Randolph TW, Glassy-state stabilization of a dominant negative inhibitor anthrax vaccine containing aluminum hydroxide and glycopyranoside lipid A adjuvants. J Pharm Sci 2015, 104 (2), 627–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hassett KJ; Cousins MC; Rabia LA; Chadwick CM; O’Hara JM; Nandi P; Brey RN; Mantis NJ; Carpenter JF; Randolph TW, Stabilization of a recombinant ricin toxin A subunit vaccine through lyophilization. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassett KJ; Meinerz NM; Semmelmann F; Cousins MC; Garcea RL; Randolph TW, Development of a highly thermostable, adjuvanted human papillomavirus vaccine. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2015, 94, 220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen TN; Fowler A; Toner M, Literature review: Supplemented phase diagram of the trehalose-water binary mixture. Cryobiology 2000, 40 (3), 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehrer AT; Lieberman MM; Wong TAS; Feldmann H; Marzi A, PRECLINICAL DEVELOPMENT OF AN EBOLA VIRUS VACCINE BASED ON RECOMBINANT SUBUNITS EXPRESSED IN INSECT CELLS. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2015, 93 (4), 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pikal MJ; Roy ML; Shah S, Mass and Heat-Transfer in Vial Freeze-Drying of Pharmaceuticals - Role of the Vial. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 1984, 73 (9), 1224–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pallesen J; Murin CD; de Val N; Cottrell CA; Hastie KM; Turner HL; Fusco ML; Flyak AI; Zeitlin L; Crowe JE; Andersen KG; Saphire EO; Ward AB, Structures of Ebola virus GP and sGP in complex with therapeutic antibodies. Nature Microbiology 2016, 1 (9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu DM; Huang SH; McClellan H; Dai WL; Syed NR; Gebregeorgis E; Mullen GED; Long C; Martin LB; Narum D; Duffy P; Miller LH; Saul A, Efficient extraction of vaccines formulated in aluminum hydroxide gel by including surfactants in the extraction buffer. Vaccine 2012, 30 (2), 189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chisholm CF; Han N. Bao; Soucie KR; Torres RM; Carpenter JF; Randolph TW, In Vivo Analysis of the Potency of Silicone Oil Microdroplets as Immunological Adjuvants in Protein Formulations. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 104 (11), 3681–3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerhardt A; Bonam K; Bee JS; Carpenter JF; Randolph TW, Ionic strength affects tertiary structure and aggregation propensity of a monoclonal antibody adsorbed to silicone oil-water interfaces. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2013, 102 (2), 429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerhardt A; McUmber AC; Nguyen BH; Lewus R; Schwartz DK; Carpenter JF; Randolph TW, Surfactant Effects on Particle Generation in Antibody Formulations in Pre-filled Syringes. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 104 (12), 4056–4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.To A; Medina LO; Mfuh KO; Lieberman MM; Wong TAS; Namekar M; Nakano E; Lai CY; Kumar M; Nerurkar VR; Lehrer AT, Recombinant Zika Virus Subunits Are Immunogenic and Efficacious in Mice. mSphere 2018, 3 (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez A; Trappier SG; Mahy BWJ; Peters CJ; Nichol ST, The virion glycoproteins of Ebola viruses are encoded in two reading frames and are expressed through transcriptional editing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1996, 93 (8), 3602–3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez A; Yang ZY; Xu L; Nabel GJ; Crews T; Peters CJ, Biochemical analysis of the secreted and virion glycoproteins of Ebola virus. Journal of Virology 1998, 72 (8), 6442–6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta RK; Rost BE, Aluminum Compounds as Vaccine Adjuvants In Vaccine Adjuvants: Preparation Methods and Research Protocols, O’Hagan D, Ed. Humana Press Inc: Totowa, NJ, 2000; pp 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maa YF; Zhao L; Payne LG; Chen D, Stabilization of alum-adjuvanted vaccine dry powder formulations: mechanism and application. J Pharm Sci 2003, 92 (2), 319–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diminsky D; Moav N; Gorecki M; Barenholz Y, Physical, chemical and immunological stability of CHO-derived hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) particles. Vaccine 1999, 18 (1-2), 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clausi A; Cummiskey J; Merkley S; Carpenter JF; Braun LJ; Randolph TW, Influence of Particle Size and Antigen Binding on Effectiveness of Aluminum Salt Adjuvants in a Model Lysozyme Vaccine. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2008, 97 (12), 5252–5262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]