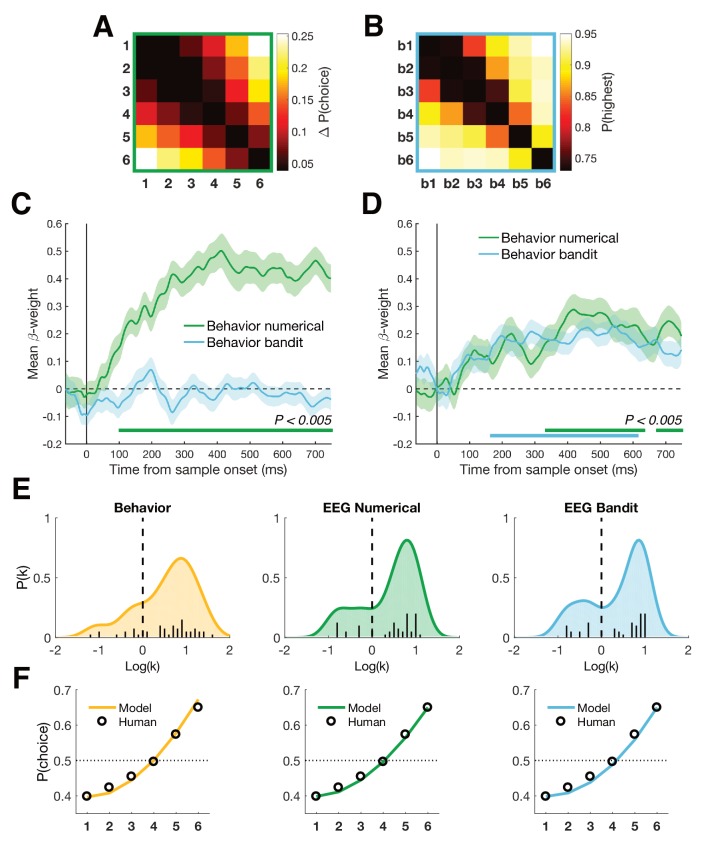

Figure 4. Behavioral analyses.

(A) Group-averaged difference RDM of decision weights in the numerical task. We calculated the weight of each number on participant’s choice, independent of color, and created a choice RDM through pairwise differences of weights. (B) Group-averaged choice RDM in the bandit task. Each cell contains the probability of choosing the highest valued bandit on trials where bandit x and bandit y were presented together. Participants never encountered trials where the same bandit was presented twice. (C) Both choice matrices were inserted in a multiple regression explaining EEG patterns to establish a potential link between behavior and neural patterns in either task. Only the numerical choice RDM explained neural patterns of the numerical task. (D) In contrast, both choice RDMs significantly explained neural patterns in the bandit task, possibly indicating that participants relied on a more general understanding of numbers in both tasks (bottom colored lines, Pcluster < 0.005). Shaded area represents SEM. (E) Distributions of after fitting a power-law model of the form to the decision weights in the numerical task (yellow) and the average neural patterns in the numerical (green) and bandit task (blue) between 350 and 600 ms (see Materials and methods). In all cases, the best fitting parameter was significantly greater than 0 (linear), indicating an overweighting/increasing dissimilarity for larger quantities (numbers 5-6 or highest valued bandits). (F) Decision weights under the median estimated for psychometric (yellow) and neurometric (green/blue) fits, compared to the median true human decision weights in the numerical task.