Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

Key Words: keratoconus, femtosecond laser, small incision, intracorneal implantation, penetrating keratoplasty

Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of small-incision femtosecond laser–assisted intracorneal concave lenticule implantation (SFII) and penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) in patients with progressive keratoconus.

Methods:

All the patients were clinically diagnosed with progressive keratoconus. Twenty patients underwent PKP (PKP group), and 11 patients underwent SFII (SFII group). Visual acuity, intraocular pressure, corneal topography, corneal visualization Scheimpflug technology, anterior segment optical coherence tomography, and in vivo confocal microscopy were analyzed.

Results:

Vision improved at 3 months postoperatively in the SFII group. In the PKP group, corrected distance visual acuity improved 1 week after surgery. Corneal topography showed a statistically significant decrease in the anterior K1 and K2. Corneal visualization Scheimpflug technology showed that changes in the biomechanical parameters of the SFII group were also statistically different from those of the PKP group. All the grafts from both groups were clearly visible by anterior segment optical coherence tomography observation. The central corneal thickness of both groups was stable during the 24-month study period. In vivo confocal microscopy showed a few dendritic cells in the subepithelial region in the SFII group. At 3 months after surgery, many dendritic cells and inflammatory cells were observed in the basal epithelium and stroma in the PKP group.

Conclusions:

Both SFII and PKP surgical procedures resulted in a stable corneal volume and improved visual acuity in this long-term study. SFII was less invasive and more efficient compared with PKP.

Keratoconus is a proinflammatory corneal disease that is characterized by progressive corneal ectasia and steepening resulting from central corneal thinning.1 It has an incidence of 0.05%, with an age range of 9 to 28 years.2–4 At present, the main operative corrections for keratoconus are corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) therapy and corneal transplantation. Collagen cross-linking therapy5 increases the biomechanical stability of the cornea.6–8 However, halting progression resulting from corneal collagen cross-linking may only be transient.9 Penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) is usually the preferred treatment to improve visual acuity.10–12 Nevertheless, the graft survival rate reduces with time postoperatively from 98% to 86% between 1 and 20 years postoperatively, respectively.13,14

Corneal intrastromal implantation was first described by Barraquer.15 This inlay model does not affect the integrity of the corneal epithelium or endothelium. However, clinical application of this model is limited because of its invasiveness during creation of the intrastromal pocket and poor inlay materials.15 In a previous study,16,17 we have shown that there was no implant rejection after autotransplantation or xenotransplantation using a small-incision femtosecond laser–assisted corneal intrastromal implantation procedure in all rhesus monkeys during a 26-month study period. We also found that the modified concave inlay lamellae changed corneal refractive power.18 In studies by Liu et al19 and Liu et al,20 allogeneic lenticules were used to change the refractive power in the animal models. Pradhan et al21 and Ganesh et al22 also found that the meniscus allogeneic lenticule from small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) could reshape the cornea with the necessary precision to correct hyperopia in the recipient. However, the concave lenticule might have more usage in keratectatic diseases, and the use of this inlay allograft corneal implantation model, assisted by the femtosecond laser, has not been explored in patients with progressive keratoconus.

In the present study, we developed a small-incision femtosecond laser–assisted intracorneal concave lenticule implantation (SFII) procedure to implant the allogeneic corneal lamella in human patients with progressive keratoconus. The feasibility and safety of the allogeneic grafts implanted using SFII and conventional PKP were compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Study Design

This is a retrospective study design. This interventional case series study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hainan Eye Hospital of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (Sun Yat-sen University, China). All research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients after explanation of the nature of the study and potential risks. All patients were diagnosed with keratoconus based on results from slit-lamp microscopy, corneal topography, corneal visualization Scheimpflug technology (CST), and anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT). A total of 31 consecutive patients (31 eyes) were enrolled in the study. Inclusion criteria were clinical evidence of progressive keratoconus,23 stage II to III keratoconus based on the Amsler–Krumeich classification system24 intolerance to any type of contact lens, transparent cornea, and normal endothelial cell density for age range. Exclusion criteria were active anterior segment pathologic features, previous corneal or anterior segment surgery, and pregnancy or lactation.

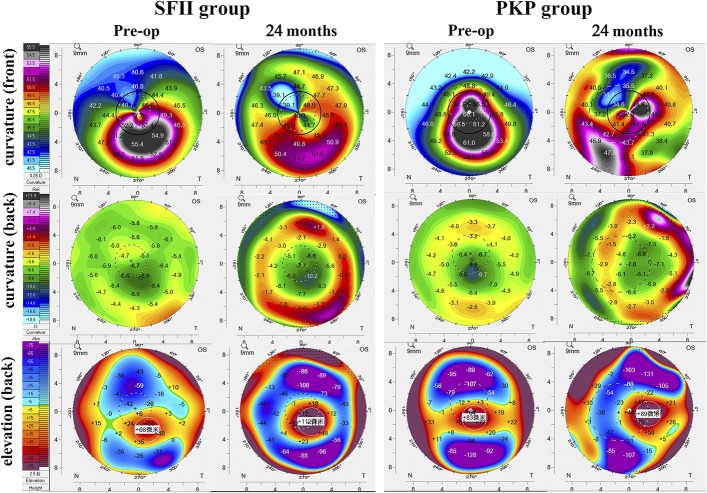

Twenty patients underwent PKP between June 2014 and March 2016 (ethics acceptance number: 2014–008). After obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee (ethics acceptance number: 2016–007), 11 patients underwent SFII between April 2016 and November 2017. Table 1 summarizes the baseline patient data.

TABLE 1.

Preoperative Patient data

Surgical Technique

All donor tissues were collected from the Hainan Eye Hospital eye bank in accordance with local guidelines (Hainan Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau of the People's Republic of China).

SFII

The donor cornea was placed into an artificial anterior chamber (AC). A lamellar incision was made using the treatment mode of femtosecond laser–assisted LK (VisuMax; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany); we used the surgical parameters described in our previous research.16 The surgical parameters were as follows: the diameter of the incision was 7.5 mm, and the incision was located at a depth of 320 μm. The next step was myopic correction of −4.00 diopters (69.59 μm thickness) under PRK (Photorefractive Keratectomy type; WaveLight GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). The lenticule was separated from the stromal bed and used as the graft. The anterior–posterior orientation of the inlay was maintained during implantation (320–69.59 = 250.41 μm thickness) (see Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/ICO/A744).

Topical anesthesia consisted of proparacaine hydrochloride eye drops (Alcaine; Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX). A myopic correction of −0.75 diopters (28 μm thickness) using a femtosecond laser system under SMILE treatment was performed on the recipient cornea. We used the femtosecond laser parameters described in our previous research.16 The surgical parameters were as follows: 160 μm cap thickness, 7.8 mm cap diameter, and 7.8 mm lamellar cornea diameter. The surgeon spread the lenticule out, producing a space that resembles a “stromal pocket” inside the corneal stroma. The graft was implanted into the “stromal pocket” (depth of implantation: 160-μm) (see Video 1, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/ICO/A746). Postoperatively, tobramycin and dexamethasone eye drops (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX) were administered 4 times per day for 1 month.

PKP

PKP was performed under general anesthesia with the anesthetist's assistance. The center of the host cornea was marked and then completely excised using a Barron vacuum trephine (Katena Products, Denville, NJ). The donor corneas were cut using a punch trephine on a Troutman guide (Medtronic Solan, Jacksonville, FL). All grafts had diameters between 7.0 and 8.0 mm. All grafts were closed with a continuous 24-bite running 10-0 nylon suture.

Postoperatively, patients received tobramycin and dexamethasone eye drops (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX) 4 times per day for 3 months and recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor (Fusion Protein, Bausch and Lomb, Rochester, NY) eye gel 3 times per day for 6 months. All eyes in the PKP group were treated with mannitol 1 time postoperatively.

Clinical Examination

Ophthalmic examinations were performed preoperatively and at 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months postoperatively. In the PKP group, the corneal sutures were removed at 12 months postoperatively.

The clinical assessment included preoperative assessment, postoperative ocular response, visual acuity, intraocular pressure (IOP), corneal topography, and corneal strength. The ocular response was assessed by slit-lamp microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), ciliary redness (Oculus Keratograph 5M; Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), AS-OCT (DRI Triton OCT; Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and in vivo confocal microscopy (HRT Ⅲ; Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). This included eyelid spasm, ciliary flush, corneal clarity and neovascularization, anterior segment imaging, and keratocyte responses. Corneal topography and AC evaluation were recorded using the Pentacam HR Scheimpflug camera (Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzler, Germany). Central corneal thickness was measured using AS-OCT. Corneal strength was evaluated by CST (Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzler, Germany).

Statistical Analysis

Visual acuity was measured using Snellen charts. For statistical analysis purposes, Snellen visual acuity was converted to the corresponding logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution value using standard conversion tables. Other outcome measures included IOP, ciliary flush grade, keratometry, AC depth, AC volume, corneal posterior maximal elevation, data from CST, and corneal thickness. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 16.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). All measurements are expressed as mean ± SD. All the data above were assessed using one-way analysis of variance. For pairwise comparisons within the group, we used either the least significance difference test or Tamhane T2. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Complications/Adverse Events

In the PKP group, 1 eye had elevated IOP and graft rejection at 3 months after surgery. This eye had to be removed from this trial.

Visual Acuity and Intraocular Pressure

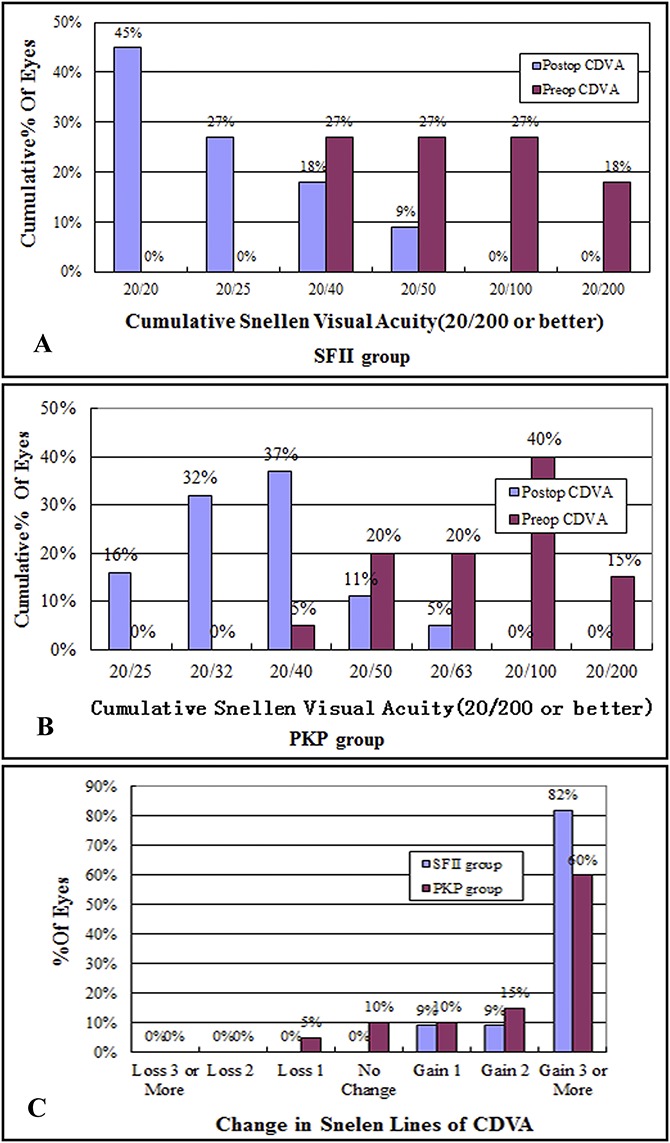

As shown in Figure 1, in the SFII group, both uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) and corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) improved at 3 months postoperatively (PUDVA = 0.004, PCDVA = 0.016) and remained stable thereafter. UDVA did not improve in the PKP group throughout the 24-month period after surgery (P24m = 0.137), and CDVA improved 1 week after surgery (P1w = 0.001) and remained stable thereafter. IOP increased in the 1-month follow-up period in the PKP group (PPKP = 0.001), and it declined to the preoperative level at 3 months postoperatively (PPKP-3m = 0.748). In the SFII group, IOP maintained a steady level during the 1-month postoperative period (PSFCII-1m = 0.594) (see Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/ICO/A745).

FIGURE 1.

Results of the 24-month follow-up period of all eyes. A and B, In both groups, CDVA at 24 months postoperatively (postop) compared with preoperative CDVA (preop). C, Change in Snellen lines of CDVA after SFII at 24 months.

Slit-Lamp Microscopy and Ciliary Redness Assessment

Figure 2 summarizes the findings on slit-lamp microscopy in both groups. In the SFII group, with regard to all implants, there were no infections or tissue degradation detected during the long-term study period. No increased ciliary redness or corneal neovascularization was observed. Graft edema greatly subsided after 1 month, and the implant boundary was smooth and visible (Fig. 2). In the PKP group, obvious ciliary redness was observed for 1 week after surgery. Fresh epithelialization occurred at 1 month postoperatively, and the margin of the graft still exhibited evident edema (Fig. 2; see also Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/ICO/A745).

FIGURE 2.

Representative appearance of the eye on slit-lamp microscopy in both groups. A, The surrounding area of the host corneal tissue maintained its transparency in all recipient eyes. At 1 week after surgery, there was pronounced stromal edema around the implant. Graft edema greatly subsided after 1 month, and the implant boundary was smooth and visible. B, By 24 months after surgery, total integration of the implant and the host stroma was evident in all recipients undergoing the SFII procedure, and there was no visible tissue boundary. C, Graft edema and ciliary redness at 1 week postoperatively. The epithelium regenerated within 1 month, but the margin of the graft still exhibited edema. At 24 months postoperatively, graft edema subsided with a smooth graft–host junction.

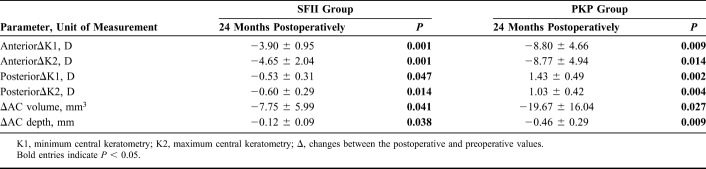

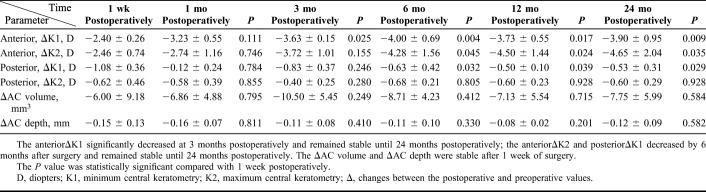

Pentacam HR Scheimpflug Camera Scanning

Table 2, Table 3, and Figure 3 summarize the corneal topographic changes. Corneal curvature maps (Fig. 3) demonstrate that changes in the corneal surface were different in the two treatment groups. In both groups, the anterior K1 and K2, AC volume, and AC depth were significantly decreased after surgery. However, the corneal posterior K1 and K2 in the SFII group also decreased after surgery, whereas the values in the PKP group had increased at 24 months postoperatively.

Table 2.

Preoperative and Postoperative Changes in Corneal Curvature in the SFII and PKP Groups

TABLE 3.

Postoperative Changes in Corneal Curvature in the SFII Group

FIGURE 3.

Postoperative Pentacam (Oculus Optikgeräte, Wetzlar, Germany) images in both groups. Corneal curvature and posterior elevation (bottom) over the 24-month postoperative course after transplantation.

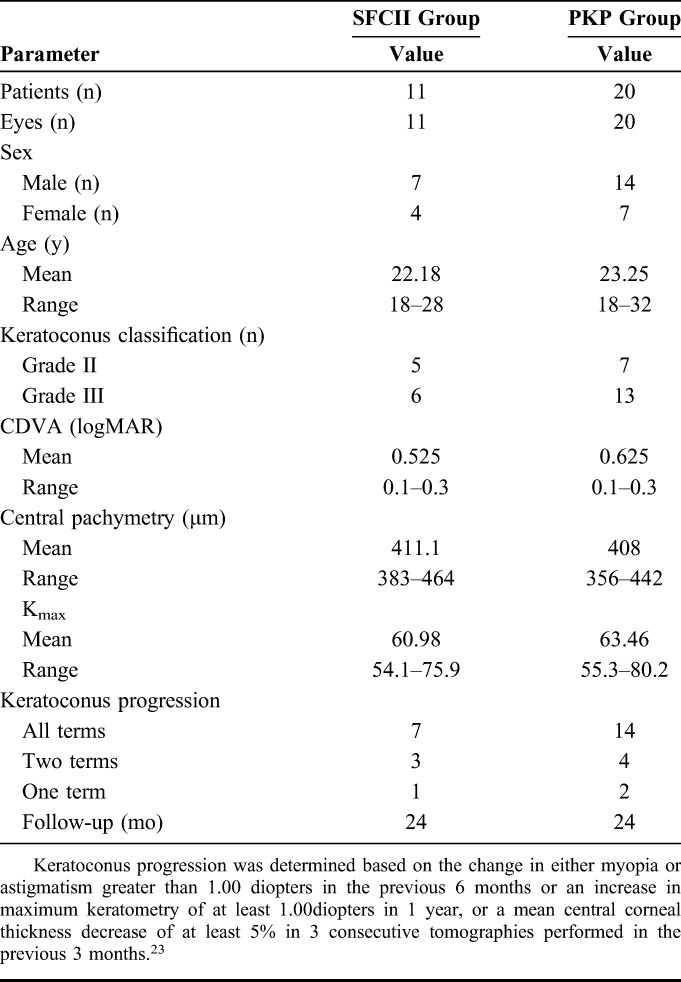

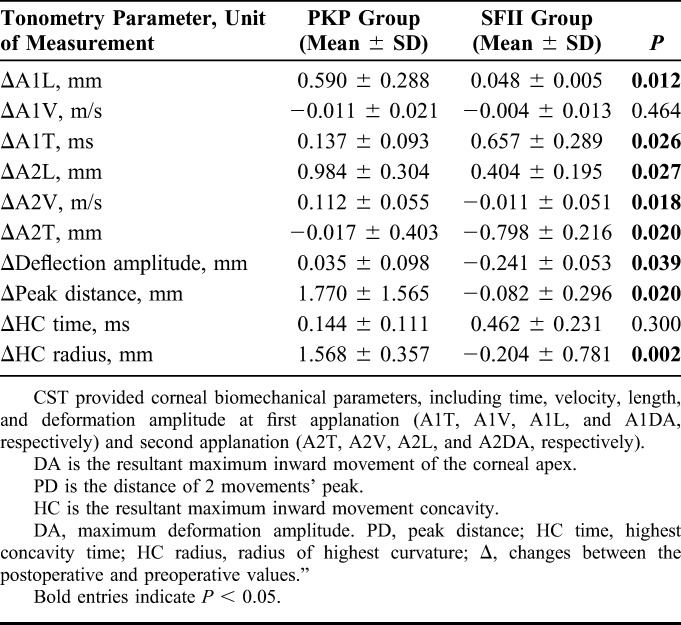

CST

Corneal biomechanics measured after surgery were different from those measured preoperatively, with changes in the SFII group much more obvious than those in the PKP group. The ΔA1L, ΔA1V, ΔA1T, andΔHC time in the SFII group were greater than those in the PKP group. In addition, the ΔA2L, ΔA2V, ΔA2T, ΔMDA, ΔPD, and ΔHC radius in the SFII group were lower than those in the PKP group (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of Corneal Visualization Scheimpflug Technology Values in the PKP and SFII Groups

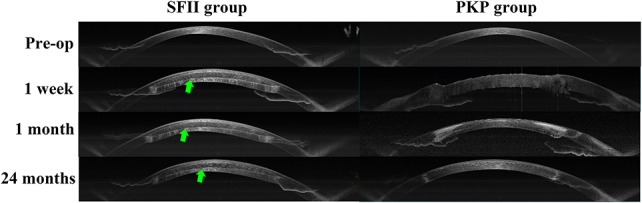

Corneal Imaging with AS-OCT

In the PKP group, the graft exhibited obvious evidence of edema on AS-OCT at 1 week postoperatively. AS-OCT in the SFII group revealed a clearly visible graft in the corneal stroma. The graft was concave, with its shape thinning centrally and thickening laterally (Fig. 4). In the SFII group, central corneal thickness was greatly increased compared with the preoperative findings. The change in thickness (ΔThickness) is defined as the comparison between the postoperative and preoperative corneal thicknesses. Postoperatively, the ΔThickness in the SFII group did not change until 24 months postoperatively (P1m = 0.901, P3m = 0.811, P6m = 0.785, P12m = 0.426, and P24m = 0.450). In the PKP group, the ΔThickness had decreased at 3 months after surgery (P1w = 0.004, P1m = 0.001) (see Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/ICO/A745).

FIGURE 4.

Representative images of corneal AS-OCT. The preoperative images showed that corneal thickness was thin. One week postoperatively, corneal thickness appeared thicker in both groups. At 1 month postoperatively, AS-OCT revealed that central corneal thickness was reduced, and the borders of the lenticule were visible. At 24 months postoperatively, the corneal shape remained stable.

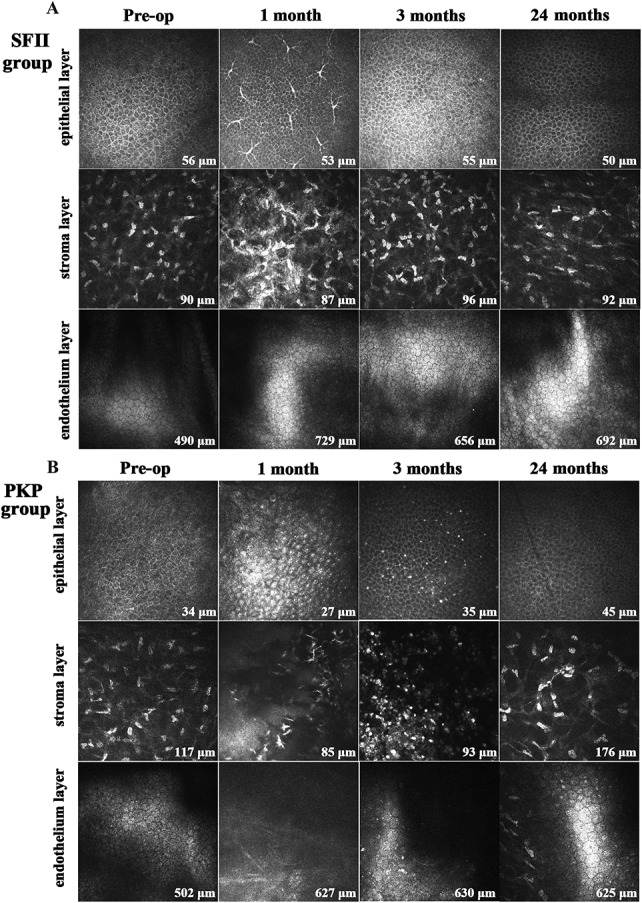

In Vivo Confocal Microscopy

In the SFII group, at 1 month postoperatively, confocal microscopy revealed dendritic cells in the subepithelial region (Fig. 5A). Dendritic and inflammatory cells could be observed at the interface between the graft and the host cornea, and there was an acellular structure with some hyperreflective and polymorphic spots arranged randomly. No dendritic or inflammatory cells were observed 3 months after surgery. The endothelial cells showed no particular change in shape and density during the follow-up period. In the PKP group, numerous dendritic cells and inflammatory cells were dispersed in the basal epithelium and stroma within 3 months after surgery. The endothelial cells had a lower-than-normal endothelial cell density and a higher coefficient of variation (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Preoperative and postoperative images of corneal confocal microscopy using the HRT III microscope (magnification, 400 × 400 μm). A, In the SFII group, some dendritic cells were found in the subepithelial region and stromal layer at 1 month postoperatively. They disappeared 3 months after surgery. Endothelial cells showed no particular change in shape or density during the study period. B, In the PKP group, many dendritic cells and inflammatory cells were dispersed in the basal epithelium and stroma within 3 months after surgery.

DISCUSSION

In both groups, corneal curvature remained stable, and both CDVA and UDVA improved until 24 months after surgery. Our findings suggest that these 2 surgical procedures can offer long-term stabilization and improve visual outcomes in those with progressive keratoconus. In the SFII group, the inlay graft was well tolerated, and the outcomes in this group indicate that the SFII procedure is efficient and minimally invasive. The implants in the SFII group were centered in the stromal pocket, which not only changed corneal curvature but also improved corneal strength. The findings of this study suggest that SFII could be a safe and efficient surgical approach, and it might halt progression of keratoconus in further studies.

Compared with PKP, the SFII procedure is minimally invasive. A major advantage of the SFII procedure is that it requires no sutures or blades, which greatly reduces the surgical time.25 Known as the “all-in-one” femtosecond laser technique, this technique allows for molding of implants, a minimal incision of 3.0 mm, and a consistent depth and thickness on every occasion.26 Therefore, this procedure does not involve any intraocular manipulations, and all surgical manipulations can be confined to a pocket within the recipient cornea. After surgery, the implanted grafts were stable with no dislodgement, as confirmed by AS-OCT. Monitoring dendritic cell changes after transplantation could provide information on graft inflammation and a graft-versus-host disease outcome.27 There were a large number of dendritic and inflammatory cells in the eyes undergoing PKP, and it took more time for these to settle. The postoperative inflammatory reaction in the PKP group may have also had a greater influence on IOP postoperatively. In each case from the SFII group, the tear film was normal, and the epithelium and endothelium were intact and healthy. In addition, the dendritic cells remained present for a short period after implantation. In addition, the endothelial cells were found to have undergone no obvious change in the SFII group. Corneal endothelium function recovered earlier than that of the PKP group. This could be the other reason why graft edema resolved faster in the SFII group compared with the PKP group. This indicates that the SFII procedure has a negligible impact on the anterior segment. In addition, this minimally invasive surgical approach could provide a precise intrastromal match between the donor inlay and the recipient.

Corneal curvature completely changed after transplantation in both groups (Fig. 3). In the PKP group, these changes were influenced by the suture and donor cornea. In the SFII group, the implanted graft was concave, as confirmed by AS-OCT (Fig. 4). As showed in Figure 3, anterior mid-peripheral corneal curvature changed more than did anterior central corneal curvature. According to the change in corneal remodeling, we confirmed that the reshaped cornea was relatively thinner centrally and thicker peripherally. Because of greater regularization of the cornea in the SFII group, vision improved more than in the PKP group. This additive implantation procedure not only increased recipient corneal thickness (250.4–28 = 222.4 μm) but also increased the strength of the host cornea, as shown by CST. This increase in strength and remodeling of the host cornea might be more stable and controllable, and it may halt progression of keratoconus in further studies.

Compared with the surgical method performed by Mastropasqua et al,28 who adopted the positive meniscus lenticules from the SMILE procedure to be the allografts and evaluated patients who had stable corneal ectasia, we used concave lenticules in the treatment of progressive keratoconus. Furthermore, Hashemi et al29 found that the corneal shape had a prolate shift, which was a similar finding of the present study. Nevertheless, it should be noted that this ring did not affect corneal thickness and that eyes with severe corneal thinning and steepening may not be eligible for the procedure.30 Bowman layer transplantation has also been shown to be beneficial in reducing ectasia in advanced keratoconus because it is a minimally invasive procedure with few postoperative complications.31 The procedure of the Bowman layer graft needs higher technology requirement and time consuming.32

The present study has its limitations and several potential applications. Because other refractive parameters are less likely to be affected by surgery, the change in corneal refractive power in the SFII group was not only decided by the refractive power of the graft inlayed, but it was also dependent on anterior and posterior deformation of corneal curvature. Further study is needed to evaluate the final corrections of the refractive powers of the inlay. This inlay procedure is an additive surgery, and it still might not improve vision in patients with an obvious corneal scar in some corneal ectatic disorders.

CONCLUSION

Using SFII, we found that the eyes maintained a stable corneal volume, and vision improved during the long-term follow-up period. The SFII procedure may provide a new treatment option for keratoconus in the future. Moreover, this technique may also provide new hope for the treatment of other corneal diseases.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870681), the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Youth (81500755), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (2017CXTD011, 817365).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design. H. Jin, L. Liu, X. Zhong, and M. He collected the data. J. Wu, H. Liu, H. Ding, and C. Zhang made substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data. He Jin wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. X. Zhong has given final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.corneajrnl.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi JA, Kim MS. Progression of keratoconus by longitudinal assessment with corneal topography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:927–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collier SA. Is the corneal degradation in keratoconus caused by matrix-metalloproteinases? Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;29:340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson SE, Lin DT, Klyce SD. Corneal topography of keratoconus. Cornea. 1991;10:2–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zadnik K, Barr JT, Edrington TB, et al. Baseline findings in the Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Keratoconus (CLEK) Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2537–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wollensak G. Crosslinking treatment of progressive keratoconus: new hope. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raiskup-Wolf F, Hoyer A, Spoerl E, et al. Collagen crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A light in keratoconus: long-term results. J Cataract Refract Surg.. 2008;34:796–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caporossi A, Mazzotta C, Baiocchi S, et al. Long-term results of riboflavin ultraviolet a corneal collagen cross-linking for keratoconus in Italy: the Siena eye cross study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toprak I, Yaylalı V, Yildirim C. Factors affecting outcomes of corneal collagen crosslinking treatment. Eye (Lond). 2014;28:41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown SE, Simmasalam R, Antonova N, et al. Progression in keratoconus and the effect of corneal cross-linking on progression. Eye Contact Lens. 2014;40:331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanai A. The pathogenesis and treatment of corneal disorders [in Japanese]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2002;106:757–776; discussion 777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keane M, Coster D, Ziaei M, et al. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty versus penetrating keratoplasty for treating keratoconus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD009700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabinowitz YS. Keratoconus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:297–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly TL, Coster DJ, Williams KA. Repeat penetrating corneal transplantation in patients with keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1538–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang YM, Wu SQ, Yao YF. Long-term comparison of full-bed deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty in treating keratoconus. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2013;14:438–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barraquer JI. Keratophakia. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1972;92:499–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin H, Liu L, Ding H, et al. Comparison of femtosecond laser-assisted corneal intrastromal xenotransplantation and the allotransplantation in rhesus monkeys. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Wang Y, He M, et al. Preliminary investigation femtosecond laser-assisted refractive lenticule transplantation in rhesus monkeys. J Sunyat-sen Univ (Medical Sciences). 2015;36:449–455. [Google Scholar]

- 18.He M, Jin H, He H, et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted small incision endokeratophakia using a xenogeneic lenticule in rhesus monkeys. Cornea. 2018;37:354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu R, Zhao J, Xu Y, et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted corneal small incision allogenic intrastromal lenticule implantation in monkeys: a pilot study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:3715–3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H, Zhu W, Jiang AC, et al. Femtosecond laser lenticule transplantation in rabbit cornea: experimental study. J Refract Surg. 2012;28:907–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pradhan KR, Reinstein DZ, Carp GI, et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted keyhole endokeratophakia: correction of hyperopia by implantation of an allogeneic lenticule obtained by SMILE from a myopic donor. J Refract Surg. 2013;29:777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganesh S, Brar S, Rao PA. Cryopreservation of extracted corneal lenticules after small incision lenticule extraction for potential use in human subjects. Cornea. 2014;33:1355–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giacomin NT, Netto MV, Torricelli AA, et al. Corneal collagen cross-linking in advanced keratoconus: a 4-year follow-up study. J Refract Surg. 2016;32:459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii R, Kamiya K, Igarashi A, et al. Correlation of corneal elevation with severity of keratoconus by means of anterior and posterior topographic analysis. Cornea. 2012;31:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blum M, Täubig K, Gruhn C, et al. Five-year results of small incision lenticule extraction (ReLEx SMILE). Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:1192–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie RZ, Evans MD, Bojarski B, et al. Two-year preclinical testing of perfluoropolyether polymer as a corneal inlay. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Killian D, Reichard M, Knueppel A, et al. Distribution changes of epithelial dendritic cells in canine cornea and mucous membranes related to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In Vivo. 2013;27:761–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mastropasqua L, Nubile M, Salgari N, et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted stromal lenticule addition keratoplasty for the treatment of advanced keratoconus: a preliminary study. J Refract Surg. 2018;34:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashemi H, Amanzadeh K, Miraftab M, et al. Femtosecond-assisted intrastromal corneal single-segment ring implantation in patients with keratoconus: a 12-month follow-up. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41:183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alió JL, Shabayek MH, Belda JI, et al. Analysis of results related to good and bad outcomes of Intacs implantation for keratoconus correction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:756–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma B, Dubey A, Prakash G, et al. Bowman's layer transplantation: evidence to date. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:433–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dragnea DC, Birbal RS, Ham L, et al. Bowman layer transplantation in the treatment of keratoconus. Eye Vis (Lond). 2018;5:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.