Abstract

Introduction:

Upper airway imaging can often identify the anatomical risk factors for sleep apnea and provide sufficient insight into the pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a case–control, observational study at a tertiary care hospital in North India. All cases and controls underwent lateral cephalometry and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for craniofacial and upper airway evaluation. Only the cases had polysomnography testing for confirmation of OSA and assessing the severity of disease.

Results:

Forty cases and an equal number of matched controls were recruited. On X-ray cephalometry, it was observed that the cases had a significantly larger hyoid mandibular distance and soft palate length; and shorter mandibular length. The MRI cephalometric variables were significantly different, the soft palate length, tongue length, and submental fat were longer while the retropalatal and retroglossal distance was shorter amongst the cases. A statistically significant positive correlation was found between the cephalometric parameters and the indices of severity of OSA. An increased hyoid mandibular distance and soft palate length, and a decrease in the lower anterior facial height were found to be predictive of severe OSA (Apnea–Hypopnea Index –>30/h). An increased hyoid mandibular distance, soft palate length, and the tongue length and a reduced mandibular length were found to be predictive of need for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) pressures of ≥15 cm H2O. There were significant differences between the cephalometric parameters of the Indian OSA patients and patients from other ethnicities reported in the literature.

Conclusions:

OSA patients had a significantly smaller upper airway compared to age-, sex-, and body mass index-matched controls and cephalometric variables correlated with the indices of OSA severity. The cephalometric assessment was also predictive of severe OSA and the need for higher pressures of CPAP. This indicates the important role of upper airway anatomy in the pathogenesis of OSA.

KEY WORDS: Obstructive sleep apnea, magnetic resonance imaging, X-ray cephalometry

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) constitutes a spectrum of disorders of varying severity ranging from intermittent snoring at one end to obesity hypoventilation syndrome at the other end of the spectrum.[1] OSA is increasingly being recognized as a disease with significant short- and long-term cardiorespiratory complications. The prevalence rate of OSA in the middle-age population was reported to be 2%–4% in Caucasians.[2] The overall prevalence of OSA in the adult population of Delhi was found to be 4.3% in a questionnaire-based study.[3]

Obesity has been frequently cited as a risk factor for OSA. However, OSA syndrome is known to occur even in nonobese patients where the other risk factors need to be ascertained. It is well recognized that OSA patients have an anatomically small upper airway with alterations in bony craniofacial structure and enlargement of surrounding soft-tissue structures;[4] this spectrum of abnormalities acting synergistically to promote upper airway obstruction during sleep. The differences in the upper airway anatomy have been used to explain why nonobese patients can develop OSA.

Upper airway imaging is often not a part of routine evaluation in the diagnosis of OSA. Evaluation of the upper airway is usually done with the help of imaging methods such as X-ray lateral cephalometry, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and nasopharyngoscopy. These different techniques are often complementary to each other; while X-ray allows only a two-dimensional detailed evaluation of the bony structures; for the three-dimensional reconstruction of the airway and soft-tissue structures (i.e., tongue, soft palate) techniques such as CT/MRI are better. Although these static imaging techniques are often not accurate in identifying the sites/sites of obstruction, they can identify the anatomic risk factors for sleep apnea and provide sufficient insight into the pathophysiology of OSA. Since individual patients have different patterns of upper airway narrowing, no single method for evaluating the obstruction appears to be complete in itself.[5]

Multiple studies have documented differences in craniofacial features among the different races.[6,7,8] Ethnic and racial differences in the upper airway dimensions need to be taken into consideration while comparing Indians with other ethnic groups. There is a paucity of data from India.[9] We conducted this study to elucidate the differences in the upper airway anatomy between Indian OSA patients and controls; compare the cephalometric characteristics between the obese and nonobese OSA patients and also to determine the ethnic variations between Indian patients and other groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a case–control observational study at a tertiary care hospital of a medical college in North India, after obtaining the institutional review board approval. Written, informed consent was obtained from the participants. The “cases” group comprised consecutive patients of either sex, 30–65 years of age, with clinical suspicion of OSA, attending the sleep clinic and willing to undergo polysomnography, arterial blood gas analysis, lateral cephalometry, and MRI. The “control” group comprised of patients visiting the hospital and undergoing an MRI for other reasons (for example undergoing MRI for evaluation of backache, headache) with no history suggestive of OSA and a negative response to the Berlin Questionnaire. The controls were matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) with the cases and were willing to undergo lateral cephalometry and MRI. Patients who had undergone any kind of maxillofacial or upper airway surgery or significant facial trauma in the past and pregnant females were excluded from the study.

Forty cases and an equal number of age-, sex-, and BMI-matched controls were recruited. All cases and controls were evaluated using predesigned pro forma for history taking and physical examination and underwent lateral cephalometry and MRI for craniofacial and upper airway evaluation. Only the “cases” had arterial blood gas analysis and polysomnography testing for confirmation of OSA and assessing the severity of disease.

Cephalometry

X-ray lateral cephalometry

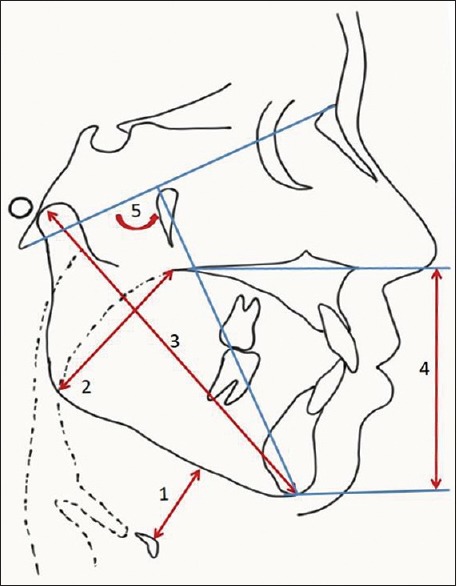

Standardized lateral digital X-ray of head and neck was obtained in standing, natural head posture at end expiration, without swallowing, in centric occlusion and analyzed for hyoid mandibular distance, soft palate length, mandibular length, lower anterior facial height, and facial axis angle [Figure 1].[7]

Figure 1.

Measurements using lateral cephalometry. 1: Hyoid mandibular Distance: Perpendicular distance between hyoid bone and mandibular plane. 2: Soft palate length: Posterior nasal spine to inferior angle of the mandible. 3: Mandibular length: The distance between condylion to gnathion. 4: Lower anterior facial height: The distance between anterior nasal spine and menton measured perpendicular to the line passing through anterior nasal spine and the posterior nasal spine. 5: Facial axis angle: The angle formed by the basion-nasion and the plane from foramen rotundum to gnathion

Magnetic resonance imaging

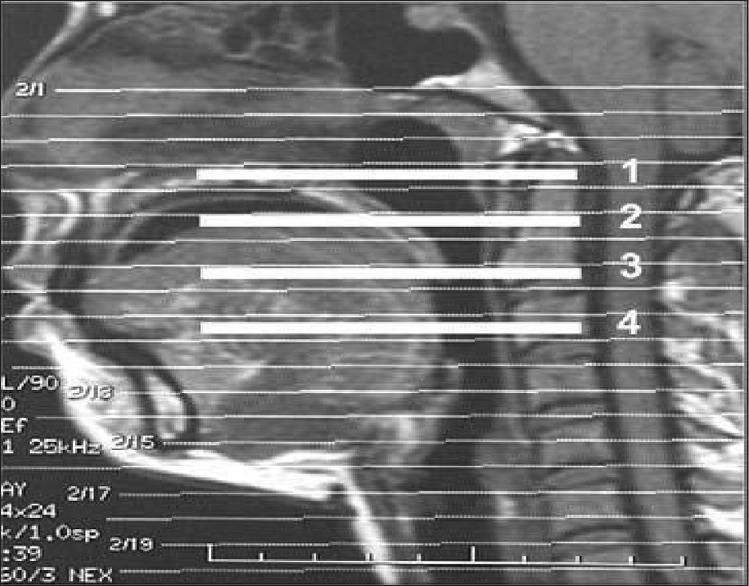

MRI of head, face, and neck was done using 1.5 Tesla Philips Achieva Scanner in supine position, while awake and both sagittal and transverse images were analyzed for soft palate length (craniocaudal), tongue length (craniocaudal), retropalatal and retroglossal oropharynx width (minimum), and submental fat thickness [Figures 2 and 3].[10]

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging sagittal section showing 1: Craniocaudal length of the tongue (maximum), 2: Craniocaudal soft palate length (maximum), 3: Submental fat thickness (maximum)

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging sagittal section showing 1: Rhinopharynx (not measured), 2: High retropalatal oropharynx, 3: Low retropalatal oropharynx, retropalatal oropharynx (minimum) – measured between 2 and 3, 4: Retroglossal oropharynx (minimum)

The aforementioned cephalometric and MRI parameters were selected because these parameters indicate the size of the oropharynx and hypopharynx and are the most commonly implicated sites of obstruction in OSA patients.[4,5,11]

Polysomnography study

Split-night polysomnography study (Alice 5 Diagnostic Sleep System, Respironics, USA) was conducted for the “cases” group in the sleep laboratory of the department and analyzed for Apnea–Hypopnea Index (AHI), Respiratory Disturbance Index, Arousal Index, and PAP requirement in OSAHS patients.

Statistical analysis

Hypotheses testing procedure was done with unpaired t-test with the level of significance set at 95% (alpha error – 5%, two-tailed test, and power – 80%). Sample size was calculated to detect a minimum difference of 2 mm in the retropalatal distance with a standard deviation of 3 mm.[10] Presence or absence of significant correlation between upper airway indices and severity of OSA was established using value of Pearson's coefficient of correlation. Further data analysis was done using t-test for numerical data and Chi-square test for categorical data. Logistic regression analysis was done to estimate the odds ratio of predicting the needs for high CPAP (>15cm H2O). The odds ratio was adjusted for the BMI.

RESULTS

Forty cases and an equal number of age-, sex-, and BMI-matched controls were recruited. The baseline characteristics of both the groups are shown in Table 1. On physical examination, the neck circumference was larger and the incidence of retrognathia was found to be significantly higher in the OSA patients. A neck circumference of 40 cm or more was observed in all the cases and none of the controls. The case group comprised of more patients in the Modified Mallampati classification Class 3 and 4 than the control group. A higher Modified Mallampati Class indicated an overall smaller oropharynx with bulky tongue.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and physical examination findings of cases and controls

| Parameter | Cases (n=40) | Controls (n=40) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.80±7.68 | 48.45±8.09 | 0.843 |

| Sex | |||

| Males | 31 | 31 | 1.000 |

| Females | 9 | 9 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.96±2.66 | 29.82±1.96 | 0.784 |

| Hypertension | 20 (50) | 4 (10) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 9 (22.5) | 2 (5) | 0.048 |

| Epworth sleepiness scale | 16.85±4.81 | 4.92±2.12 | <0.001 |

| Clinical examination | |||

| Mean neck circumference (cm) | 43.28±1.97 | 36.00±1.01 | <0.001 |

| Deviated nasal septum | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Hypertrophied inferior nasal turbinate | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.494 |

| Retrognathia | 13 (32.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0.001 |

| High-arched palate | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0.057 |

| Modified Mallampati classification | |||

| Class 1 | 4 (10) | 6 (15) | 0.007 |

| Class 2 | 9 (22.5) | 20 (50) | |

| Class 3 | 21 (52.5) | 14 (35) | |

| Class 4 | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | |

BMI: Body mass index

On comparing the X-ray cephalometric parameters between the cases and controls [Table 2], it was observed that the hyoid mandibular distance and the soft palate length were significantly larger among the cases and the mandibular length was significantly shorter in OSA patients. All the MRI cephalometric variables were significantly different between the two groups, the soft palate length, the tongue length, and the submental fat were longer while the retropalatal and the retroglossal distance was shorter among patients with OSA. The length of the soft palate was measured using both lateral cephalometry as well as MRI and the measurements were consistent and comparable using both methods (correlation r = 0.998; P < 0.001). We also observed that patients had multiple cephalometric variables beyond the normal range, suggesting a reduction in the airway size at multiple levels. When we compared the cephalometric variables between the obese and nonobese OSA patients [Table 2], it was observed that the obese patients had a smaller airway dimension compared to nonobese patients thought the amount of submental fat in both the groups was comparable.

Table 2.

Comparing various cephalometric parameters between cases and controls and between the obese and the nonobese obstructive sleep apnea patient

| Parameter | Mean±SD (95%CI) | P | Mean±SD (95%CI) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Obese OSA | Nonobese OSA | |||

| X-ray lateral cephalometry | ||||||

| Hyoid mandibular distance (mm) | 20.35±4.17 (19.02-21.68) |

8.25±0.87 (7.97-8.53) |

<0.001 | 21.90±3.31 (20.35-23.45) |

18.80±4.43 (16.73-20.87) |

0.017 |

| Soft palate length (mm) | 47.35±4.17 (46.02-48.68) |

35.12±1.32 (34.70-35.55) |

<0.001 | 48.80±3.19 (47.31-50.29) |

45.90±4.59 (43.75-48.05) |

0.026 |

| Mandibular length (mm) | 90.05±3.99 (88.77-91.33) |

112.05±1.84 (111.46-112.64) |

<0.001 | 88.70±4.32 (86.68-90.72) |

91.40±3.20 (89.90-92.90) |

0.031 |

| Lower anterior facial height (mm) | 73.78±5.52 (72.01-75.54) |

74.68±5.24 (73.00-76.35) |

0.457 | 72.60±5.88 (69.85-75.35) |

74.95±5.01 (72.61-77.29) |

0.182 |

| Facial axis angle (°) | 99.82±5.15 (98.18-101.47) |

100.62±4.26 (99.26-101.99) |

0.451 | 100.05±6.29 (97.10-103.00) |

99.60±3.84 (97.80-101.40) |

0.786 |

| MRI variables | ||||||

| Soft palate length (mm) | 47.32±4.12 (46.01-48.64) |

35.12±1.32 (34.70-35.55) |

<0.001 | 48.70±3.15 (47.23-50.17) |

45.95±4.58 (43.81-48.09) |

0.033 |

| Tongue length (mm) | 74.18±4.74 (72.66-75.69) |

71.50±3.72 (70.31-72.69) |

0.006 | 75.65±4.17 (73.70-77.60) |

72.70±4.92 (70.40-75.00) |

0.048 |

| Retropalatal distance (mm) | 4.05±0.99 (3.73-4.37) |

8.10±0.59 (7.91-8.29) |

<0.001 | 4.10±1.21 (3.53-4.67) |

4.00±0.73 (3.66-4.34) |

0.753 |

| Retroglossal distance (mm) | 13.35±1.33 (12.92-13.78) |

17.30±0.72 (17.07-17.53) |

<0.001 | 13.15±1.59 (12.40-13.90) |

13.55±0.99 (13.08-14.02) |

0.349 |

| Submental fat (mm) | 14.12±1.68 (13.59-14.66) |

9.15±0.95 (8.85-9.45) |

<0.001 | 14.45±1.50 (13.75-15.15) |

13.80±1.82 (12.95-14.65) |

0.226 |

SD: Standard deviation, CI: Confidence interval, OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

A statistically significant positive correlation was found between the cephalometric parameters and the indices of severity of OSA [Table 3]. Logistic regression analysis was done to determine the cephalometric variables significantly predictive of severe OSA (defined as an AHI of >30/h) [Table 4], it was seen that an increased hyoid mandibular distance was found to be predictive of severe OSA (odds ratio [OR] = 1.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.18, 2.89. P = 0.007). In addition, it was seen that an increased lower anterior facial height lowered the risk of severe OSA (OR = 0.86; 95% CI = 0.74, 0.99. P = 0.045). It was also observed that an increase of the soft palate length by 1 mm almost doubled the risk of having severe OSA. A similar analysis [Table 4] was done to look for parameters predictive of high continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (CPAP of ≥15 cmH2O) requirement – an increased hyoid mandibular distance, soft palate length, and the tongue length and a reduced mandibular length were predictive of need for CPAP pressures of ≥15 cmH2O.

Table 3.

Correlation of cephalometric indices with the neck circumference and the polysomnography findings

| Upper airway parameter | Neck circumference (n=80) | RDI (n=40) | AHI (n=40) | AI (n=40) | CPAP pressure (n=40) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient (r) | P | Correlation coefficient (r) | P | Correlation coefficient (r) | P | Correlation coefficient (r) | P | Correlation coefficient (r) | P | |

| X-ray lateral cephalometry | ||||||||||

| Hyoid mandibular distance | 0.906 | <0.001 | 0.825 | <0.001 | 0.843 | <0.001 | 0.420 | 0.007 | 0.909 | <0.001 |

| Soft palate length | 0.910 | <0.001 | 0.810 | <0.001 | 0.823 | <0.001 | 0.432 | 0.005 | 0.891 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular length | −0.915 | <0.001 | −0.590 | <0.001 | −0.597 | <0.001 | −0.420 | 0.007 | −0.563 | <0.001 |

| Lower anterior facial height | −0.130 | 0.250 | −0.180 | 0.265 | −0.178 | 0.271 | 0.019 | 0.906 | −0.146 | 0.369 |

| Facial axis angle | −0.077 | 0.500 | 0.121 | 0.458 | 0.118 | 0.470 | 0.268 | 0.095 | 0.207 | 0.200 |

| MRI variables | ||||||||||

| Soft palate size | 0.910 | <0.001 | 0.800 | <0.001 | 0.814 | <0.001 | 0.432 | 0.005 | 0.895 | <0.001 |

| Tongue length | 0.347 | 0.002 | 0.525 | <0.001 | 0.528 | <0.001 | 0.398 | 0.011 | 0.611 | <0.001 |

| Retropalatal distance | −0.865 | <0.001 | −0.246 | 0.125 | −0.242 | 0.133 | −0.310 | 0.052 | −0.347 | 0.028 |

| Retroglossal distance | −0.831 | <0.001 | −0.267 | 0.096 | −0.269 | 0.093 | −0.274 | 0.087 | −0.255 | 0.112 |

| Submental fat thickness | 0.978 | <0.001 | 0.496 | 0.001 | 0.508 | <0.001 | 0.249 | 0.122 | 0.535 | <0.001 |

RDI: Respiratory Disturbance Index, AHI: Apnea-Hypopnea Index, AI: Arousal index, CPAP: Continuous positive airway pressure, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

Table 4.

Logistic regression model for predicting severe obstructive sleep apnea and predicting the need for high continuous positive airway pressure (>15 cm H2O)

| Variable | Logistic regression model for predicting severe OSA | Logistic regression model for predicting need for high CPAP pressure (>15 cm H2O) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | OR Adjusted for BMI | ||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age | 1.04 | 0.95-1.14 | 0.326 | 0.98 | 0.89-1.06 | 0.595 | - | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.15 | 0.89-1.49 | 0.294 | 1.58 | 1.13-2.22 | 0.008 | - | ||

| Neck circumference (cm) | 1.47 | 0.96-2.23 | 0.074 | 1.41 | 0.96-2.06 | 0.078 | - | ||

| X-ray cephalometry | |||||||||

| Hyoid mandibular distance (mm) | 1.85 | 1.18-2.89 | 0.007 | 6.11 | 1.69-22.11 | 0.006 | 5.44 | 1.49-19.87 | 0.010 |

| Soft palate length (mm) | 1.92 | 1.22-3.00 | 0.004 | 2.89 | 1.26-6.65 | 0.012 | 2.62 | 1.11-6.17 | 0.028 |

| Mandibular length (mm) | 0.87 | 0.73-1.04 | 0.122 | 0.68 | 0.54-0.87 | 0.003 | 0.75 | 0.58-0.98 | 0.038 |

| Lower anterior facial height (mm) | 0.86 | 0.74-0.99 | 0.045 | 0.94 | 0.83-1.06 | 0.285 | 0.94 | 0.82-1.08 | 0.394 |

| Facial axis angle (°) | 0.99 | 0.87-1.13 | 0.917 | 1.05 | 0.92-1.20 | 0.460 | 1.00 | 0.87-1.16 | 0.956 |

| MRI cephalometry | |||||||||

| Soft palate length (mm) | 1.92 | 1.21-3.05 | 0.006 | 3.07 | 1.29-7.30 | 0.011 | 2.86 | 1.14-7.23 | 0.026 |

| Tongue length (mm) | 1.08 | 0.94-1.24 | 0.281 | 1.24 | 1.03-1.51 | 0.022 | 1.15 | 0.94-1.41 | 0.159 |

| Retropalatal distance (mm) | 0.97 | 0.51-1.87 | 0.933 | 0.31 | 0.11-0.86 | 0.024 | 0.29 | 0.09-0.94 | 0.039 |

| Retroglossal distance (mm) | 0.89 | 0.54-1.49 | 0.665 | 0.83 | 0.51-1.37 | 0.472 | 0.88 | 0.52-1.48 | 0.634 |

| Submental fat (mm) | 1.45 | 0.94-2.23 | 0.090 | 1.62 | 1.04-2.52 | 0.033 | 1.42 | 0.86-2.31 | 0.162 |

BMI: Body mass index, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, CPAP: Continuous positive airway pressure, OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea

The values of various anthropometric and upper airway indices obtained using lateral cephalometry and MRI in the OSA patients were compared with the corresponding values published in the literature to find any significant differences due to ethnic variations [Table 5]. On comparing the neck circumference and BMI with the other ethnicities, it was observed that the Indian patients had a greater BMI and larger neck circumference than the Far East Asians. Hyoid mandibular distance and mandibular length were significantly smaller in Indian OSA patients as compared to the Caucasians, suggesting a smaller hypopharynx in the Indian OSA patients as compared to the Caucasians. In comparison with the Japanese patients, mandibular length was significantly smaller in our OSA patients, whereas hyoid mandibular distance and the facial axis angle were significantly greater in the Indians. In comparison with studies reported from Brazil, the Indian OSA patient had a significantly larger soft palate length.

Table 5.

Comparison of the anthropometric and cephalometric variables between different ethnic populations

| Indian OSA patients (n=40), Mean±SD | Caucasian OSA patients | Far East OSA patients | Brazilian OSA patients | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors (References) | n | Mean±SD | P (compared to Indian patients) | Authors (References) | n | Mean±SD | P (compared to Indian patients) | Authors (Ref) | n | Mean±SD | P (compared to Indian patients) | ||

| Anthropometric parameters | |||||||||||||

| BMI | 29.96±2.66 | Lam et al.[12] | 75 | 30±7 | 0.972 | Lam et al.[12] | 164 | 29±4 | 0.151 | Borges et al.[13] | 93 | 27.68±3.83 | <0.001 |

| Liu et al.[14] | 43 | 27.41±2.45 | <0.001 | Liu et al.[14] | 30 | 26.98±2.49 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Li et al.[15] | 293 | 30.7±5.9 | 0.435 | Li et al.[15] | 58 | 26.6±3.7 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Sforza et al.[16] | 57 | 31.6±5.7 | 0.094 | Kawaguchi et al.[17] | 189 | 27.3±4.8 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Neck Circumference | 43.28±1.97 | Lam et al.[12] | 75 | 41±4 | 0.001 | Lam et al.[12] | 164 | 40±3 | <0.001 | Borges et al.[13] | 93 | 38.56±3.92 | <0.001 |

| Sforza et al.[16] | 57 | 43.4±3.8 | 0.855 | Kawaguchi et al.[17] | 189 | 40.3±3.6 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Cephalometric parameters | |||||||||||||

| Hyoid mandibular distance (mm) | 20.35±4.17 | Liu et al.[14] | 43 | 26.27±6.27 | <0.001 | Liu et al.[14] | 30 | 26.31±6.91 | <0.001 | Borges et al.[13] | 93 | 19.21±8.22 | 0.407 |

| Li et al.[18] | 50 | 26.4±7.1 | <0.001 | Li et al.[18] | 50 | 18.7±6.5 | 0.167 | ||||||

| Sforza et al.[16] | 57 | 25.7±5.7 | <0.001 | Kikuchi et al.[19] | 31 | 22.4±8.8 | 0.198 | ||||||

| Soft palate length (mm) | 47.35±4.17 | Liu et al.[14] | 43 | 46.42±5.89 | 0.412 | Liu et al.[14] | 30 | 46.21±4.95 | 0.300 | Borges et al.[13] | 93 | 39.84±5.37 | <0.001 |

| Sforza et al.[16] | 57 | 47.2±4.9 | 0.875 | Kikuchi et al.[19] | 31 | 44.7±5.9 | 0.030 | ||||||

| Mandibular length (mm) | 90.05±3.99 | Liu et al.[14] | 43 | 122.30±6.29 | <0.001 | Liu et al.[14] | 30 | 118.56±7.46 | <0.001 | ||||

| Sforza et al.[16] | 57 | 123.0±6.3 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Lower anterior facial height (mm) | 73.78±5.52 | Sforza et al.[16] | 57 | 73.5±5.8 | 0.811 | ||||||||

| Facial axis angle (°) | 99.82±5.15 | Kikuchi et al.[19] | 31 | 79.8±4.7 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Soft palate length (mm) | 47.32±4.12 | Rodenstein et al.[20] | 10 | 47±7 | 0.851 | ||||||||

| Ciscar et al.[21] | 17 | 39.1±4.9 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Retropalatal distance (mm) | 4.05±0.99 | Rodenstein et al.[20] | 10 | 4±1 | 0.887 | ||||||||

| Retroglossal distance (mm) | 13.35±1.33 | Rodenstein et al.[20] | 10 | 13±5 | 0.691 | ||||||||

BMI: Body mass index, OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea, SD: Standard deviation

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that OSA patients had a significantly smaller upper airway compared to age-, sex-, and BMI-matched controls and cephalometric variables correlated with the indices of OSA severity. The cephalometric assessment was also predictive of severe OSA and the need for higher pressures of CPAP. This indicates the important role of upper airway anatomy in the pathogenesis of OSA which is independent of obesity.

A high-arched palate, long uvula, tonsil enlargement, retrognathia, and obesity have been commonly reported in OSA patients.[22] The current study identified a higher Mallampati score, retrognathia, and an increased neck circumference as risk factors for OSA. Ardelean et al.[23] in a study from Europe had suggested a neck circumference cutoff of 41 cm, while in a study from Korea, Kang et al.[24] determined the cutoff value for predicting OSA to be 34.5 cm. We observed that a neck circumference of 40 cm or more identified all the patients with OSA in our study population.

The hyoid mandibular distance was significantly increased, suggesting a lower placed hyoid bone in patients with OSA. Similar findings have been reported by Sforza et al.[16] who suggested that the increased hyoid mandibular distance causes greater upper airway collapsibility. The hyoid bone position is believed to be crucial for pharyngeal patency and an imbalance between suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles may influence the hyoid bone position.[16] Skinner et al.[25] who investigated the efficacy of a titratable mandibular advancement splint (MAS) found that the baseline hyoid mandibular distance was the only cephalometric variable associated with a successful clinical outcome with the MAS.

The soft palate length was longer and the mandibular length was shorter in OSA patients than controls. This was further compounded by a larger tongue in such patents, causing a significant reduction in the size of the oropharynx. A large soft palate has been reported to be a common risk factor for OSA by Ciscar et al.[21] and Sforza et al.[16] Furthermore, pharyngeal occlusion likely occurs when the mandible is smaller or receded.[26] Kim et al.[27] reported that tongue volume and tongue fat were significantly enlarged in American patients with OSA when compared to obese controls. However, Okubo et al.[28] from Japan did not find any significant difference in the tongue volume between OSA patients and controls. This might be due to ethnic differences. In the current study, we also observed the tongue length to be larger in the obese OSA patients than in the nonobese OSA patients thought the submental fat was comparable between the groups.

The retropalatal and retroglossal distance in OSA patients was significantly lower as compared to controls indicating obstruction at the oropharynx level as an important pathogenetic factor. Our results were consistent with the findings of Ciscar et al.[25] and Hora et al.[29]

We also demonstrated that OSA patients had upper airway narrowing at multiple levels (retropalatal, retroglossal, shorter mandible, larger tongue, and lower hyoid bone position) with a combination present in most of the patients. Shellock et al.[30] and Suto et al.[31] had demonstrated multiple levels of occlusion and narrowing in the airway of OSA patients. The finding that the mixed type of pharyngeal obstruction was present in more than half of the patients has important clinical implications. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) is the most common surgical procedure for patients with OSA. The success rate is related to the site of obstruction, with patients demonstrating retropalatal obstruction having better results than those with retroglossal obstruction.[32,33] For patients in whom both retropalatal and retroglossal narrowing is seen, a surgery directed at advancing the tongue (e.g., geniohyoid advancement or maxillomandibular advancement) in addition to UPPP may be needed.

The current study showed that the lower anterior facial height and facial axis angle did not differ significantly between the cases and the control group. In contrast, Kikuchi et al.[19] reported significantly lower facial axis angle and increased lower anterior facial height in the OSA patients. This, however, does not appear to be an important factor in Indian OSA patients indicative of important ethnic variations in the pathogenesis.

When we compared the obese and the nonobese patients, it was seen that the obese patients have a larger soft palate and tongue, and associated anteroinferior positioning of the hyoid bone; suggesting a synergistic contribution of obesity and craniofacial factors to upper airway collapsibility. The crowding of the airway space through enlargement of the soft tissues could be the main catalyst for increased upper airway collapse in obese patients.

Ethnicity incorporates multiple factors such as obesity and craniofacial morphology, which will individually or in combination influence OSA.[2] While Asian patients with OSA are generally less obese than their Caucasian counterparts, craniofacial abnormalities such as a low hyoid bone and retroposition of the maxilla or mandible are common predisposing factors for OSA in the Asian populations.[34] In comparison, the Indian patients were found to be obese compared to Asians and to have smaller mandibular length compared to other ethnic groups. This suggests important differences in the bony facial structure and possible hints at a prominent role of MASs in the treatment of Indian OSA patients. Among soft-tissue parameters, tongue length was significantly smaller in Indian patients as compared to the Far East Asians, suggesting a less important role of tongue volume in the pathogenesis and treatment of OSA in Indian patients.

Strengths and limitations

The critical factors responsible for control of pharyngeal patency remain controversial. Two hypotheses have been proposed to explain the tendency of patients with OSA to collapse: aneural hypothesis implying reduced dilator muscle activity and an anatomic theory suggesting an anatomic narrowing of the upper airway. While we have assessed the anatomical factors in the current study, we also need to understand the contribution of neural factors; further studies using dynamic MRI and drug-induced sleep endoscopy will allow assessment of the dilator muscle activity.

Our study compared the craniofacial characteristics in OSA patients with BMI-matched controls, thus eliminating the impact of obesity on the upper airway profile. Use of MRI helped in better delineation of soft-tissue abnormalities and exact computerized measurements of several variables without exposing patients to unnecessary radiation. We also used an overnight PSG in all the patients and assessed the severity along with the CPAP pressures needed to treat the OSA. However, we could not do polysomnography to rule out OSA in the control group, although the sleep questionnaires were negative for the presence of OSA. The small sample size of the study limits the generalizability of the finding, and further studies are suggested.

Another limitation was that we compared the ethnic variations in upper airway indices of our OSA patients with the published literature, the effect of publication bias cannot be negated and the two groups might not be comparable.

CONCLUSIONS

The significant differences in the upper airway indices of OSA patients in comparison to BMI-matched controls signify the importance of anatomical features in the pathogenesis of OSA. The correlation of upper airway indices with the severity of OSA further demonstrates the impact of small changes in upper airway caliber on the severity of the disease. The identification of multiple sites of upper airway obstruction in majority of patients has important therapeutic implications. There may be differential contributions of craniofacial cephalometric dimensions and obesity to OSA between ethnic groups and particular ethnicities may be more vulnerable to changes in this relationship, such based on their anatomical substrate. More studies are needed to understand the complexity and interaction of OSA craniofacial phenotypes with obesity and also to assess the impact of ethnicity on these relationships.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein MD, Chicoine SA, Hanumara RC. Detection of upper airway resistance syndrome using a nasal cannula/pressure transducer. Chest. 2000;117:1073–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S, et al. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suri JC, Sen M, Adhikari T. Epidemiology of sleep disorders in the adult population of Delhi: A questionnaire based study. Indian J Sleep Med. 2008;3(4):128–137. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwab RJ. Imaging for the snoring and sleep apnea patient. Dent Clin North Am. 2001;45:759–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Togeiro SM, Chaves CM, Jr, Palombini L, Tufik S, Hora F, Nery LE, et al. Evaluation of the upper airway in obstructive sleep apnoea. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:230–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JH, Gansukh O, Amarsaikhan B, Lee SJ, Kim TW. Comparison of cephalometric norms between Mongolian and Korean adults with normal occlusions and well-balanced profiles. Korean J Orthod. 2011;41:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ioi H, Nakata S, Nakasima A, Counts AL. Comparison of cephalometric norms between Japanese and Caucasian adults in antero-posterior and vertical dimension. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:493–9. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavitha L, Karthik K. Comparison of cephalometric norms of Caucasians and non-Caucasians: A forensic aid in ethnic determination. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2012;4:53–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thapa A, Jayan B, Nehra K, Agarwal SS, Patrikar S, Bhattacharya D, et al. Pharyngeal airway analysis in obese and non-obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Med J Armed Forces India. 2015;71:S369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniel MM, Lorenzi MC, da Costa Leite C, Lorenzi-Filho G. Pharyngeal dimensions in healthy men and women. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2007;62:5–10. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322007000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hui DS. Craniofacial profile assessment in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2009;32:11–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam B, Ip MS, Tench E, Ryan CF. Craniofacial profile in asian and white subjects with obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax. 2005;60:504–10. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borges Pde T, Filho ES, Araujo TM, Neto JM, Borges NE, Neto BM, et al. Correlation of cephalometric and anthropometric measures with obstructive sleep apnea severity. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:321–8. doi: 10.7162/S1809-977720130003000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Lowe AA, Zeng X, Fu M, Fleetham JA. Cephalometric comparisons between Chinese and Caucasian patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;117:479–85. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(00)70169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li KK, Powell NB, Kushida C, Riley RW, Adornato B, Guilleminault C, et al. A comparison of asian and white patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1937–40. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sforza E, Bacon W, Weiss T, Thibault A, Petiau C, Krieger J, et al. Upper airway collapsibility and cephalometric variables in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:347–52. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9810091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawaguchi Y, Fukumoto S, Inaba M, Koyama H, Shoji T, Shoji S, et al. Different impacts of neck circumference and visceral obesity on the severity of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:276–82. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li KK, Kushida C, Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A comparison between Far-East Asian and White men. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1689–93. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200010000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikuchi M, Higurashi N, Miyazaki S, Itasaka Y. Facial patterns of obstructive sleep apnea patients using Ricketts’ method. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54:336–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2000.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodenstein DO, Dooms G, Thomas Y, Liistro G, Stanescu DC, Culée C, et al. Pharyngeal shape and dimensions in healthy subjects, snorers, and patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax. 1990;45:722–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.10.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciscar MA, Juan G, Martínez V, Ramón M, Lloret T, Mínguez J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pharynx in OSA patients and healthy subjects. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:79–86. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17100790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YC, Eun YG, Shin SY, Kim SW. Prevalence of snoring and high risk of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in young male soldiers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:1373–7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.9.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ardelean C, Dimitriu D, Frent S, Marincu I, Lighezan D, Mihaicuta S. Sensitivity and specificity of neck circumference in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 15];Eur Respir J. 2014 44(Suppl 58):2293. Available from: https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/44/Suppl_58/P2293 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang HH, Kang JY, Ha JH, Lee J, Kim SK, Moon HS, et al. The associations between anthropometric indices and obstructive sleep apnea in a Korean population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skinner MA, Robertson CJ, Kingshott RN, Jones DR, Taylor DR. The efficacy of a mandibular advancement splint in relation to cephalometric variables. Sleep Breath. 2002;6:115–24. doi: 10.1007/s11325-002-0115-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson KA, Love LL, Ryan CF. Effect of mandibular and tongue protrusion on upper airway size during wakefulness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1748–54. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim AM, Keenan BT, Jackson N, Chan EL, Staley B, Poptani H, et al. Tongue fat and its relationship to obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2014;37:1639–48. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okubo M, Suzuki M, Horiuchi A, Okabe S, Ikeda K, Higano S, et al. Morphologic analyses of mandible and upper airway soft tissue by MRI of patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Sleep. 2006;29:909–15. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.7.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hora F, Nápolis LM, Daltro C, Kodaira SK, Tufik S, Togeiro SM, et al. Clinical, anthropometric and upper airway anatomic characteristics of obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration. 2007;74:517–24. doi: 10.1159/000097790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shellock FG, Schatz CJ, Julien P, Steinberg F, Foo TK, Hopp ML, et al. Occlusion and narrowing of the pharyngeal airway in obstructive sleep apnea: Evaluation by ultrafast spoiled GRASS MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:1019–24. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.5.1566659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suto Y, Matsuo T, Kato T, Hori I, Inoue Y, Ogawa S, et al. Evaluation of the pharyngeal airway in patients with sleep apnea: Value of ultrafast MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:311–4. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.2.8424340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, Roth T. Surgical correction of anatomic azbnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923–34. doi: 10.1177/019459988108900609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shepard JW, Jr, Thawley SE. Evaluation of the upper airway by computerized tomography in patients undergoing uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:711–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui DS, Ko FW, Chu AS, Fok JP, Chan MC, Li TS, et al. Cephalometric assessment of craniofacial morphology in Chinese patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Respir Med. 2003;97:640–6. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2003.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]