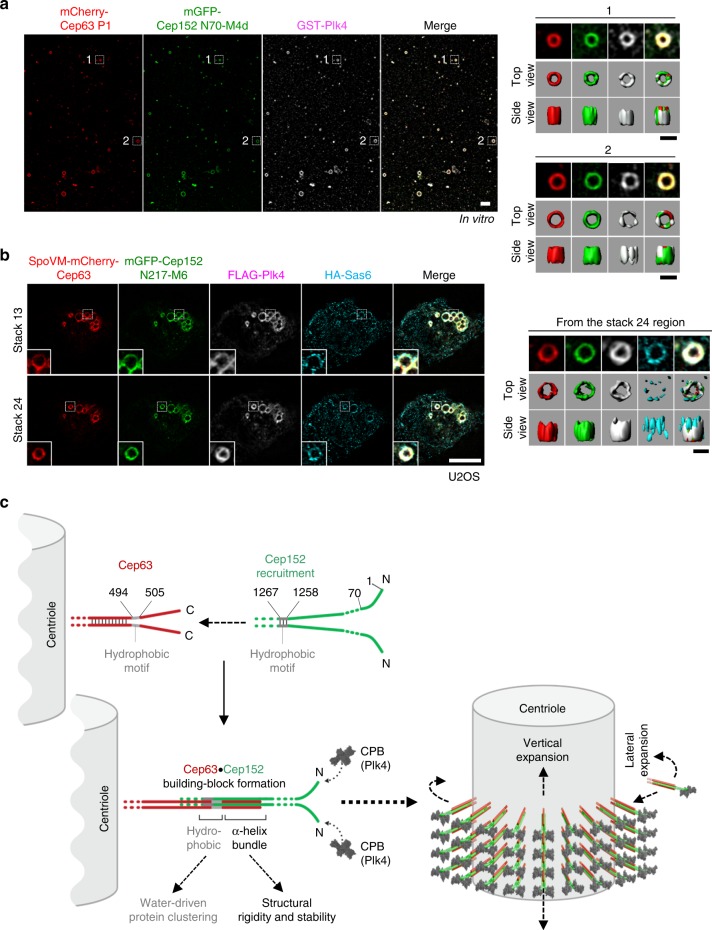

Fig. 5.

Recruitment of Plk4 and Sas6 by the Cep63-Cep152 self-assembly. a Three-dimensional structured-illumination microscopy (3D-SIM) analysis showing the ability of Cep63 P1•Cep152 N70-M4d self-assemblies to recruit Plk4 in an N70 (a minimal Plk4-binding motif)-dependent manner in vitro (see Methods for details). Surface rendering (right) is generated from the assemblies marked by dotted boxes. Bar, 1 μm; bar for rendered image, 0.5 μm. b 3D-SIM analysis of transfected U2OS cells showing the ability of Cep63•Cep152 N217-M6 self-assemblies to recruit Plk4 and Sas6 (see details in Methods). Surface rendering (right) from the assembly marked in Stack 24 (dotted box). Bar, 5 μm; bar for rendered image, 0.5 μm. c Model illustrating how Cep63 and Cep152 interact to form a heterotetrameric α-helical bundle and self-assemble into a higher-order cylindrical architecture at the proximal end of centrioles. The process of forming the four-helix bundle is explained in Supplementary Fig. 4c. We propose that the four-helix bundle functions in concert with the adjacent hydrophobic moiety to achieve the radial arrangement of the Cep63•Cep152 complex in the Cep152 N terminus-outward fashion (see Discussion for details). The resulting self-assembly appears to be a highly dynamic architecture, constantly exchanging its components with those in the surroundings