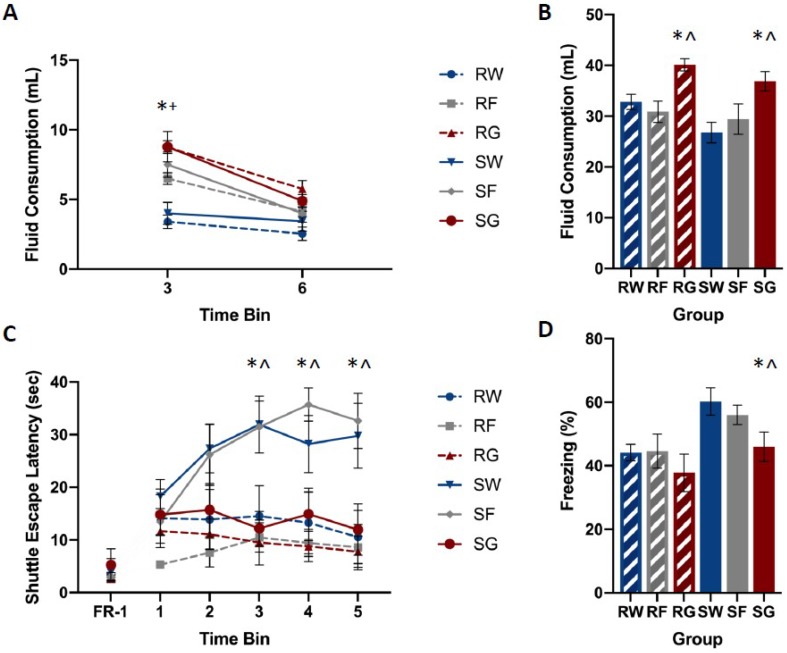

Figure 3.

Mean fluid consumption at 3 and 6 h post-stress (panel A) and 18 h post-stress (panel B), escape latencies (panel C), and percent freezing for FR-1 trials (panel D) among groups. Rats were exposed to inescapable shock (S) or restraint (R) over a 110-min period. Rats from each stress condition had free access to water (W), a concentrated glucose solution (G), or a concentrated fructose solution (F) for 18 h, beginning immediately following stress. Shuttle-box testing occurred 24 h later. Rats were exposed to five FR-1 trials of the foot-shock. These trials were run from one side to the other shut-off shock. The amount of time spent freezing between trials was measured. Twenty-five FR-2 trials, which were broken into five groups of five, required two shuttle-crossings to shutoff shock. The time it took for required shuttle crossings was measured during each trial. Shocked animals that received glucose performed similarly to restraint controls, while animals that received water or fructose following shock exhibited increased escape latencies and freezing during testing. Rats that received glucose or fructose consumed more during the first three hours after trauma compared to their water-drinking counterparts. Rats that received post-stress glucose consumed more fluid over the 18-h period compared to rats that received water or fructose. Error bars denote mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 (comparison: SG, SW), ^ p < 0.05 (comparison: SG, SF), + p < 0.05 (comparison: SF, SW).