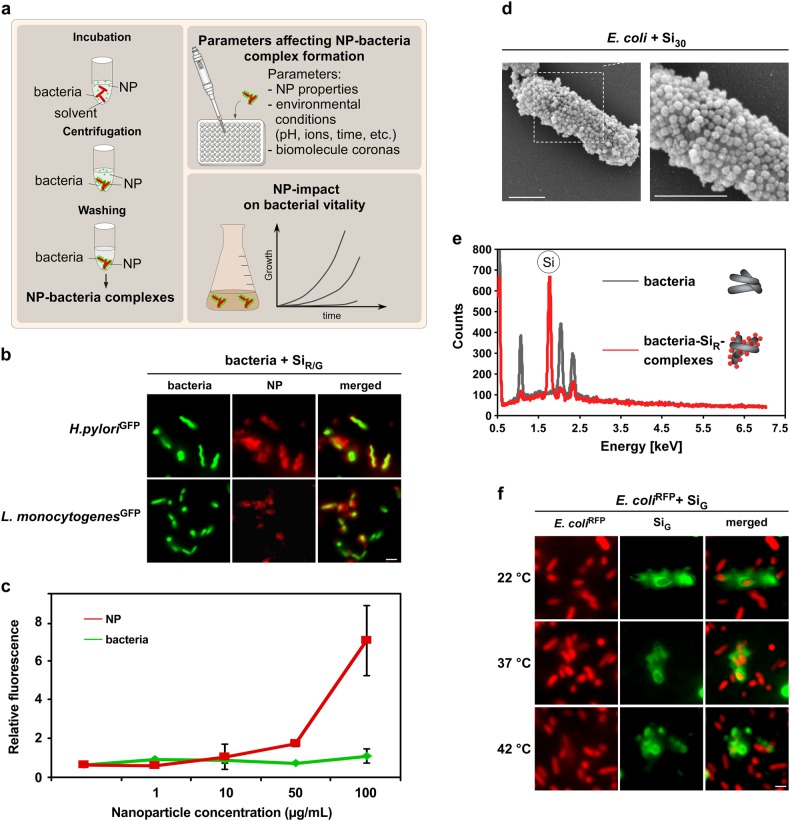

Fig. 1.

NPs rapidly and stably adsorb to H. pylori and other enteric pathogens. a Workflow to analyze material and environmental parameters affecting NP–pathogen interactions. Following co-incubation in media, such as PBS or simulated physiological fluids, NP–bacteria complexes can be harvested by mild centrifugation. Unattached pristine NPs remain in the supernatant and are removed. NP–bacteria complex formation can be analyzed via different methods after various time points under variable experimental conditions to investigate their impact on complex formation. b In situ complex formation of pristine NPs with autofluorescent pathogens. Indicated living bacteria were incubated with pristine fluorescent silica NPs (SiR/G) as shown in a, and analyzed by microscopy without fixation. Scale bar 2 µm. c Quantification of NP–bacteria interaction using the ArrayScanVTI automated microscopy platform. 1 × 106 red fluorescent bacteria were incubated with the indicated concentrations of green fluorescent pristine NPs, and complexes analyzed in 96-well plates. A minimum of 1000 NP–bacteria complexes/well was analyzed for green and red fluorescence in triplicates using the TargetActivation assay. Increasing concentrations of NPs resulted in increased binding to bacteria. Red and green fluorescence intensity of complexes is displayed. As a control, the signal of GFP-expressing bacteria remains constant. d SEM visualizing assembly of pristine Si NP onto E. coli. Exposure: 10 min in PBS. Scale bars 1 µm. e Si NP detected on the surface of H. pylori by EDX. Elemental Si was absent on bacteria. f Variations in temperature (8–42 °C) during NP–bacteria incubation (5 min, PBS) did not affect NP-assembly. Complex formation was analyzed by live cell microscopy. Scale bars 2 µm. Images are representative of three independent experiments