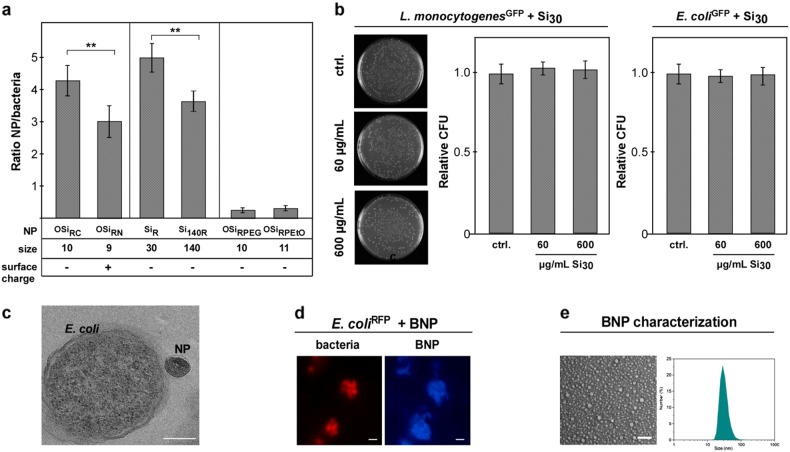

Fig. 2.

NPs’ physicochemical characteristics affect complex formation but not bacterial vitality. a NP size, charge, and stealth modification affect NP–H. pylori assembly. Quantification of NP (red)–H. pylori (green) interaction by automated microscopy. Reduced binding was observed for positively (OSiRN; ζ = +24 mV) versus negatively (OSiRC; ζ = −32mV) charged polymer NPs. Compared to small SiR (∅ ~30 nm), larger silica Si140R (∅ ~140 nm) displayed reduced binding. Stealth modification of polymer NPs (OSiRPEG/OSiRPEtO) reduced complex formation. Assays were performed in triplicates using pristine NPs. b Even high concentrations of pristine silica NPs (Si) did neither affect the vitality and growth of commensal microbes nor of tested enteric pathogens. CFU-assays of L. monocytogenesGFP and E. coli 24 h after NP exposure are shown. c TEM demonstrating that exposure of E. coli to pristine Si NP did not result in bacterial cell wall damage or NP internalization. Exposure: Si140 (∅ ~140 nm) 600 µg/mL, 60 min in PBS. Scale bar 150 nm. d Autofluorescent NPs isolated from beer (BNP; blue) adsorb to E. colimCh (red). Left: Living bacteria were incubated with pristine BNP (∅ ~50 nm) for 10 min in PBS and analyzed by microscopy without fixation. Scale bar 2 µm. Right: SEM and DLS to determine BNP size distribution. Scale bar 150 nm