Abstract

Fatty acids (FAs) are potent organic compounds that not only can be used as an energy source during nutrient deprivation but are also involved in several essential signaling cascades in cells. Therefore, the balance of intake of different dietary FAs is critical for the maintenance of cellular functions and tissue homeostasis. A diet with an imbalanced fat composition creates a risk for developing metabolic syndrome and various musculoskeletal diseases, including osteoarthritis (OA). In this review, we summarize the current state of knowledge and mechanistic insights regarding the role of dietary FAs such as saturated FAs, omega-6 polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs), and omega-3 PUFAs on joint inflammation and OA pathogeneses. In particular, we review how different types of dietary FAs and their derivatives distinctly affect a variety of cells within the joint, including chondrocytes, osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and synoviocytes. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of FAs on metabolic behavior, anabolic and catabolic processes, as well as the inflammatory response of joint cells, may help identify therapeutic targets for the prevention of metabolic joint diseases.

Keywords: obesity, cartilage, bone, synovium, arthritis, diabetes

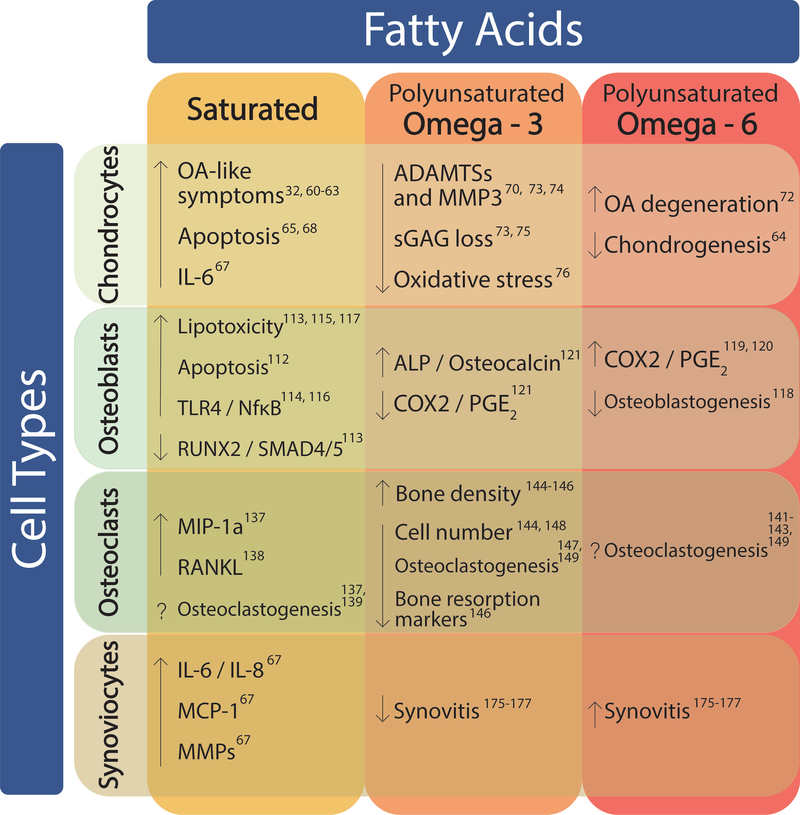

Graphical Abstract:

Fatty acids are involved in essential signaling cascades in cells, and a diet with an imbalanced fat composition can cause musculoskeletal diseases such as osteoarthritis. This article reviews the current state of knowledge regarding how dietary fatty acids affect the different cell types of the joint and play a role in joint inflammation and osteoarthritis.

Introduction

Dietary fatty acids (FAs) provide an important energy source, participate in cell signaling cascades, and function as building blocks for various molecules, but also serve as essential mediators of inflammation. Therefore, the balance of FA intake is critical for the maintenance of cellular functions and tissue homeostasis. Recent studies suggest that a diet containing an excess of saturated fatty acids (SFAs) or a high ratio of pro-inflammatory omega-6 polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs) to anti-inflammatory omega-3 PUFAs may lead to diet-induced obesity and several obesity-related comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease, and musculoskeletal disorders, including joint diseases such as osteoarthritis (OA).1–3

OA is a painful and debilitating joint disease characterized by the degeneration of cartilage, remodeling of the surrounding bone, and pathologic changes in many joint tissues.4 The synovial joint comprises a variety of tissues and cell types necessary for overall joint function. Articular cartilage is a thin connective tissue, covering the load-bearing surfaces of long bones in this joint. The unique matrix composition of cartilage provides a nearly frictionless surface during joint movement. Chondrocytes, as the only cells in cartilage, maintain the cartilage matrix through a homeostatic balance of matrix synthesis and degradation. The bone tissue directly underlying cartilage in the joint is termed subchondral bone, which can be further divided into the subchondral bone plate and the trabecular bone in the epiphysis. This trabecular compartment is highly vascularized and provides nutrients to the deep zones of cartilage. Subchondral bone is a dense, specialized structure that responds to the loads applied to the joint.5 Osteoblasts and osteoclasts are the main cells responsible for bone formation and resorption, respectively. Another tissue type found in the articular joint is the synovium. Synovial tissue consists of two layers: intima and subintima. The inner layer—the intima—consists of two types of cells: fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) and macrophage-like synoviocytes (MLS). FLS are important in the secretion of the proteins hyaluronan and lubricin, which maintain the viscosity of the synovial fluid and are believed to contribute to joint lubrication, while MLS may function as tissue-resident macrophages. Additional tissue types, including menisci, ligaments, tendons, and adipose depots such as the infrapatellar fat pad (IPFP), all contribute to the biomechanical stability and function of the joint.

It has been reported that obesity is the number one preventable risk factor for OA development.6 Historically, the link between obesity and OA was primarily attributed to biomechanical factors with the conventional thought that increased body weight due to obesity increases wear and tear on the joints. However, it is now clear that OA development involves active cells processes and has been correlated with an increase in the production of both matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS). In particular, MMP-1, −3, −9, and −13 and ADAMTS-4 and −5 have been shown to be elevated in OA7. These enzymes are mainly responsible for extracellular matrix degradation, cartilage and bone damage, and synovial inflammation. Additionally, OA is characterized by the loss of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and alterations in collagen ultrastructure.

While biomechanical factors play a critical role in the onset of post-traumatic OA,8 growing evidence suggests that the chronic inflammation and dietary imbalance associated with obesity may play a more important role than body weight in metabolic OA.9 For example, extreme obesity in mice due to impaired leptin signaling did not increase the incidence of knee OA when compared with wild-type control mice, suggesting a role for diet-associated inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in OA development.10 Moreover, obesity-related metabolic changes may directly affect cartilage, meniscus,11 synovium, synovial fluid,12 and other joint tissues at the molecular and cellular levels. For example, dietary FAs and obesogenic factors may change how the cells within the joint tissue sense and respond to mechanical loading. In particular, signaling of the mechanosensitive ion channel transient receptor vanilloid 4 (TRPV4), which is highly expressed in cartilage and bone, was altered by omega-3 fatty acid13 and various factors associated with metabolic syndrome, such as leptin and resistin.14 Furthermore, TRPV4-deficient mice had increased susceptibility to obesity and obesity-associated OA under a high-fat diet feeding regimen.15 These results indicate that mechanosensitive pathways in cartilage may be modulated by dietary FAs.

Interestingly, the makeup and concentration of fatty acids may also play a role in the pathogenesis of OA, with various direct and indirect effects on the joint tissues including cartilage, bone, and synovium. However, the precise role of dietary and circulating FA within articular joints remains controversial. Here, we review the literature investigating the role of FAs on a variety of cell types within the synovial joint, including chondrocytes, osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and synoviocytes, in the context of OA as a whole-joint disease.4 We focus on cell signaling pathways mediated by FA and their receptors, with an emphasis on dysregulation caused by dietary FA content associated with obesity.

Pleiotropic functions of fatty acids

Fatty acids play multiple crucial roles in cells; most importantly, providing the key energy source under nutrient starvation. During FA degradation (e.g., FA β-oxidation), cells are able to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is then used as a chemical fuel by the cells.16 FAs, particularly long-chain FAs, can also be incorporated into phospholipids, maintaining cell integrity by regulating membrane fluidity and permeability.3 Extracellular FAs are also potent signaling molecules; for instance, palmitic acid (PA) is postulated to mediate Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling.17 For these roles, FAs can be introduced into the mammalian cell or be synthesized within the cytoplasm. However, for the scope of this review, we will focus primarily on the influence of extracellular FAs.

Fatty acid categorization

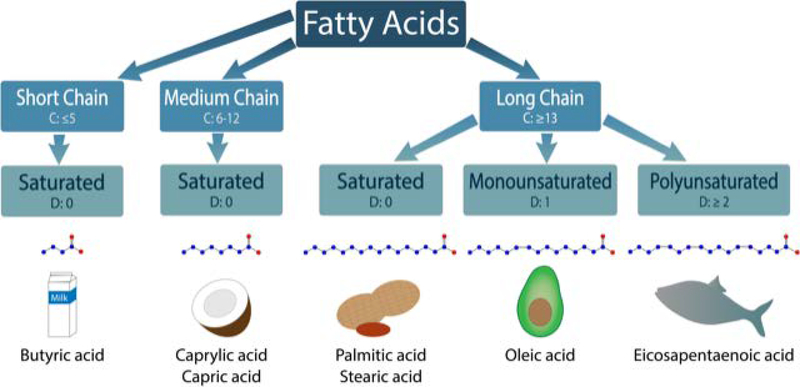

Naturally occurring, biologically functional FAs can be categorized by several parameters indicative of their chemical structure. Based on the length of their carbon chain, they are named short- (5 or fewer), medium- (6–12), or long-chain (13 or more). FAs can also be categorized as saturated FAs (SFAs) or unsaturated FAs based on the absence or presence of a double bond. Depending on the number of double bonds, the unsaturated FAs can be further divided into monounsaturated FAs (MUFA) and polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs), as summarized in Figure 1. Additionally, the site of the final double bond in the chemical structure, relative to the tail end (e.g., omega) of the molecular chain, is used to further define the FA structure (e.g., omega-3, omega-6).

Figure 1.

Categorization of fatty acids. Fatty acids are characterized based on the number of carbons (C represents number of carbon atoms present) and the bonds between those carbons (D represents the number of double bonds). Short chain FAs have 5 or less carbons, medium chain have between 6 and 12 carbons, and long chain have 13 or more. Fatty acids that contain no double bonds between carbons are considered to be saturated. Butyric acid (found in milk), caprylic and capris acids (found in coconut oil), and palmitic and stearic acids (found in peanut oil) are examples of saturated short, medium, and long chain fatty acids, respectively. Monounsaturated have one double bond (e.g., oleic acid in avocado oil), while polyunsaturated have two or more (e.g., eicosapentaenoic acid in fish oil). In the fatty acid schematic, blue circles represent carbon while red circles represent the oxygen of the carboxylic acid group.

SFAs such as palmitic acid [16:0] (PA) and stearic acid [18:0] (SA) can be found in mammalian animal fats, including lard. MUFAs such as oleic acid [18:1] are typically found in plant-based oils, including olive and avocado oil. PUFAs can be further categorized into omega-3 or omega-6 PUFAs. Docosahexaenoic [22:6] (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid [20:5] (EPA) are omega-3 PUFAs, while arachidonic acid [22:4] (ARA) and linoleic acid [18:2] (LA) belong to omega-6 PUFAs. Most omega-3 PUFAs can be found in flaxseed and fish oil, and omega-6 FAs are enriched in meat, eggs, and soybean oil.

Omega-6 PUFAs, particularly arachidonic acid (ARA), are precursors to several pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and prostaglandins (PGs) through the arachidonic acid cascade (reviewed by Saini and Keum18). On the other hand, omega-3 PUFAs are precursors for anti-inflammatory molecules called resolvins and protectins, which are believed to mediate the resolution of acute inflammation (reviewed by Kohli and Levy19). Therefore, omega-6 PUFAs are often referred to as pro-inflammatory, while omega-3 PUFAs are called anti-inflammatory FAs. Nevertheless, it is important to note that omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs are both required for maintaining human health, and a pro- or anti-inflammatory response to these PUFAs may depend on cell type and context. Although human beings are capable of synthesizing many types of FAs (i.e., non-essential FAs), some FAs (i.e., α-linolenic and linoleic acids) rely on dietary intake. The FAs that must be acquired through diet are termed essential FAs and are critical for maintaining human health.

Fatty acid trafficking and cellular uptake

Dietary FAs are transported primarily in plasma by either fatty acid-albumin complexes or structures called lipoproteins. Lipoproteins include chylomicrons and high-, low-, and very low-density lipoproteins (HDL, LDL, and VLDL, respectively). Lipoproteins primarily consist of triglycerides, phospholipids, cholesterol, and proteins, and play a role in lipid transport from the intestine to all the other cells within the organism.

Two important groups of membrane receptors, LDL receptors (LDLRs) and LDL-related receptors (LRPs), detect lipoprotein structures and are important in mediating the cellular transport and signaling of lipids. LDLR and LRP belong to the endocytic type of receptors, which mediate the internalization and lysosomal delivery of the entire lipoprotein complex to cells. In addition, CD36 (or fatty acid translocase; FAT) belongs to the family of scavenger receptors which also binds lipoproteins but mediates only FA translocation to cells.20 A recent study suggests that cellular uptake of oxidized LDL via CD36 binding is dependent upon specific FA types and doses.21, 22 Therefore, extracellular FAs can be introduced into cells by being incorporated into the lipid membrane or through FA transport proteins.

Fatty acid and cellular signaling

Recent studies demonstrated that FAs can directly signal through several types of membrane receptors. The most widely described family of FFA receptors are G protein-coupled receptors: FFAR1-FFAR4, with FFAR1 (GPR40) and FFAR4 (GPR120) being the primary members. GPR40 and GPR120 play a key role in binding long-chain PUFAs. The most potent ligands for GPR40 are omega-3 PUFAs (e.g., DHA and EPA, as reviewed by Hara et al.23). However, SFAs, such as PA, were also shown to bind to this receptor.24 GRP120 can be stimulated by both omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs, and is known to mediate anti-inflammatory effects in several cell types.25

In addition, SFAs and oxidized LDL have been shown capable of activating Toll-like receptors (TLRs). These pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) are known to mediate important inflammatory signaling cascades through pathogen recognition. It was originally hypothesized that, due to the structural similarity between SFAs and lipid A (an endotoxin of lipopolysaccharide), SFAs are direct ligands for TLR4 and thus can elicit inflammation in the absence of pathogens. However, several lines of accumulating evidence argue against SFAs as direct agonists of TLR4.26, 27 Using macrophages as a cellular model, Lancaster et al. recently demonstrated that TLR4-dependent priming, which alters cellular metabolism and the membrane lipidome, is required for the inflammatory effects of SFAs (i.e., SFAs act as a secondary trigger following TLR4 activation).17 Despite the fact that mechanisms by which SFAs activate TLR4-dependent inflammation still remain under intensive investigation, there is compelling evidence that TLR4 plays an important role in mediating obesity-induced inflammation.

FAs can also influence intracellular receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). PPARs, consisting of PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ, are able to bind oleic and linoleic acids as well as their metabolites, including prostaglandins or oxidized phospholipids.28 The PPAR family can also bind to retinoid X receptor (RXR) and control the transcription of a number of genes involved in adipogenesis, inflammation, and lipid metabolism. For example, PPARα regulates genes involved in FA β-oxidation and is mostly found in liver and skeletal muscles.28, 29 PPARβ/δ is also involved in fatty acid oxidation, while PPARγ is known to be involved in regulation of adipogenesis, energy balance, and lipid biosynthesis.28 It is important to emphasize that many studies investigating the PPAR family and other FA receptors in cells utilize chemical agonists. Although these agonists provide significant insights into the role of receptors in many cellular processes, they may not completely recapitulate the bindings between FAs and their receptors.

Cartilage and fatty acids

Cartilage and energy metabolism

Cartilage homeostasis is maintained through a balance of chondrocyte anabolic and catabolic activities. Although chondrocytes, the main resident cell population in cartilage, rely primarily on glucose as their source of energy, FAs and lipids are also believed to play a role in maintaining homeostasis.30 The chondrocyte cell membrane contains large amounts of cholesterol, while phospholipids play an important role in the maintenance of healthy cartilage and joint lubrication. FAs can either be integrated into the chondrocyte primarily in the form of triacylglycerols and phosphatidylcholine,31 or they can mediate signaling through a variety of receptors. The imbalance of energy uptake from a high fat obesogenic diet was shown to affect cartilage metabolism, indicating the potential correlation between diet and OA.32

Fatty acid receptors in chondrocytes

Chondrocytes express membrane receptors both for FAs and lipoproteins, including GPR4033 and GPR120,34 TLR4,35 and CD36,36 as well as some members of the LDLR and LRP families.37–39 Global knockout of GPR40 has been shown to increase predisposition to injury-induced OA in a mouse model and, when challenged with IL-1β, the GPR40−/− chondrocyte produced more inflammatory molecules, such as IL-6, PGE2, MMP-2 and MMP-9, compared with wild-type cells.33 Interestingly, Dehne and co-workers reported that GPR40 is up-regulated in human OA chondrocytes.40 The discrepancy between these two studies may result from the differences in investigated species. Nevertheless, the detailed molecular mechanisms by which GPR40 modulates OA development requires further investigation. Global GPR120 knock-out accelerates OA development in the early phase of OA in mice.34 Similarly, patients with OA have significantly down-regulated GPR120 expression in cartilage compared with healthy individuals,34 although the PUFA receptors GPR40 and GPR120 have not been extensively studied in chondrocytes. The activation of the TLR4 receptor by SFAs in chondrocytes has been investigated and reviewed.41 In brief, TLR4 mediates pro-catabolic signals in cartilage, decreasing cartilaginous matrix synthesis,42 while inhibition of these pro-catabolic signals suppresses inflammatory arthritis.43

The LRP5-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway has been shown to down-regulate type II collagen production, while up-regulating MMP-3 and MMP-13 synthesis.39 Particularly, increased expression of β-catenin in chondrocytes induces cartilage degradation. As shown by Zhu et al., cartilage-specific overexpression of β-catenin induced an OA phenotype by increased expression of MMP-3, MMP-13 and collagen X, which suggests that low density lipoprotein signaling is crucial for chondrocyte homeostasis.44 In addition, both LRP5 and CD36, a potential marker of hypertrophic chondrocytes, were up-regulated in human OA cartilage.36, 39, 45 In contrast, two other members of the LRP family have protective roles in OA: LRP1 is a potent clearing agent of ADAMTS-438 while LRP4 induces extracellular matrix production and facilitates chondrocyte differentiation.37

The family of PPAR nuclear receptors has been intensively studied regarding their role in cartilage, and the presence of PPARδ,46 PPARα, and PPARγ47 have been confirmed. Although naturally occurring long-chain PUFAs and their metabolites are known ligands for the PPARs, most of the current knowledge about these receptors is based on the use of synthetic agonists: fenofibrates for PPARα, thiazolidinediones (TZD) for PPARγ, and GW501516 for PPARδ. PPARα agonists have been shown to inhibit inflammation, catabolism,48 and the pro-inflammatory effects of IL-1β49 in human OA cartilage. Contrarily, PPARδ has been shown to promote OA50 as its agonists increase catabolic gene expression and robust fatty acid oxidation in chondrocytes.51

PPARγ has been the most studied member of the PPAR family in this context. Activation of PPARγ diminishes the pro-inflammatory effect of IL-1β by downregulating MMP-1 expression in chondrocytes.52 Furthermore, this activation can inhibit major pro-inflammatory signaling pathways in cartilage and reduce catabolism (reviewed by Giaginis et al.53). In addition, the PPARγ agonist pioglitazone prevented glucose-mediated overexpression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), PGE2, MMP-13, and IL-6, as well as loss of type II collagen caused by elevated glucose.54 Cartilage-specific deletion of PPARγ impaired cartilage growth and led to abnormal endochondral ossification,55 increased cartilage degradation, chondrocyte apoptosis, and induced mTOR signaling.56 Dysregulation of mTOR signaling is observed in morbidities such as diabetes, obesity, and cancer. Furthermore, cartilage-specific mTOR deletion was shown to inhibit OA progression57. In OA, PPARγ is down-regulated by IL-1β in cartilage.58 Interestingly, advanced-glycation end products (AGEs) also down-regulate PPARγ expression in human chondrocytes.59 AGEs are proteins or lipids that become glycated and are known to increase during aging as well as in OA. Yang et al. showed AGEs mediated down-regulation of PPARγ via TLR-4 signaling in human chondrocytes, which suggests the importance of FA receptors in modulating chondrocytes’ response to pro-inflammatory stimuli.59

Chondrocytes and SFAs

Several studies, including ours, have demonstrated that animals fed a high-fat diet rich in SFAs exhibited accelerated development of spontaneous or injury-induced OA.32, 60–63 Long-chain SFAs have been linked to a negative regulation of chondrocyte metabolism and cartilage homeostasis. Our previous study also showed that chondrocytes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and adipose stem cells (ASCs) isolated from high-fat-diet-induced obese mice had decreased cartilaginous matrix production.64 In humans, PA has been shown to induce apoptosis in chondrocytes,65 while SA induced pro-inflammatory cytokines through lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-dependent lactate production.66 Miao et al. proposed that the elevated SFA content induces lactate-mediated hypoxia-induced factor alpha (HIF-1a) and VEGF production, which will then initiate a pro-inflammatory cascade and OA progression.66 SFAs (e.g., PA and SA) and a MUFA (oleic acid) have been shown to increase pro-inflammatory markers, including IL-6, in human chondrocytes.67 Furthermore, PA, in synergy with IL-1β, mediated cartilage damage and chondrocyte apoptosis through TLR4 signaling68 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The effects of fatty acids on joint cells. Saturated, omega-3 polyunsaturated, and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids can have positive and negative effects on the various cells of the joint. In chondrocytes, SFAs and omega-6 PUFAs have more negative effects on cartilage, increasing OA, degeneration, and cell death, while omega-3 PUFAs have a more beneficial effect. Inflammation appears to be positively regulated by SFAs and omega-6 PUFAs in osteoblasts, while mineralization and osteoblastogenesis are negatively regulated. Omega-3 PUFAs have been shown to have the opposite effect. In osteoclasts, there is conflicting evidence as to whether SFAs and omega-6 PUFAs up-regulate or down-regulate osteoclastogenesis. Omega-3 PUFAs were shown to increase bone density as opposed to omega-6 PUFAs, which increased bone resorption. Synovitis was decreased in response to omega-3 PUFAs, while it was increased by omega-6 PUFAs. In addition, synoviocytes expressed higher inflammatory and degenerative markers in the presence of SFAs.

Chondrocytes and PUFAs

PUFAs may play a dual role in chondrocyte and cartilage homeostasis. Growing evidence suggests that an increased ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 FAs may be detrimental to cartilage. A high-fat diet rich in omega-6 FA increased the severity of cartilage damage in OA, while a similar diet rich in omega-3 FA ameliorated OA in mice.12 Furthermore, dietary omega-3 FAs were found to reduce OA in a guinea pig model69 and a lower ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 FAs in the diet has been shown to suppress MMP-13 in inflammatory arthritis in rats70 (Fig. 2). While the mechanisms of these effects are not fully understood, it has been hypothesized that omega-3 FAs serve as precursors for anti-inflammatory mediators such as resolvins and protectins, while omega-6 FAs are generally metabolized to pro-inflammatory prostanoids.1

Prostaglandins, derivatives of ARA, have been shown to inhibit chondrocyte differentiation through activation of protein kinases A and C (PKA and PKC).71 Both PKA and PKC are downstream effectors of PG receptors and are postulated to influence chondrocytes differentiation by activating transcription factors important in collagen X production. Prostaglandin E synthase-1 (PGES), important in mediating PGE2 synthesis downstream of COX2, has been shown to be up-regulated in OA.72 Both PGES and COX2 are known enzymes converting ARA to PGs and mediating its potential pro-inflammatory role. Conversely, omega-3 PUFAs and their metabolites appear to have a protective effect on chondrocytes and cartilage. These FAs have been shown to decrease mRNA levels of many OA-associated pro-inflammatory enzymes (such as ADAMTS and MMP3)73, 74 as well as sGAG loss in mouse75 and bovine cartilage.73 EPA inhibited oxidative-stress-induced apoptosis in human chondrocytes, and intra-articular injection of EPA mitigated OA progression.76 Additionally, DHA has been shown to ameliorate cartilage damage through a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism77 (Fig. 2). MAPK intracellular signaling is known to mediate pro-catabolic responses in cartilage. Additionally, Wang et al. proposed that DHA selectively blocks IL-1β-induced p38 activation in the MAPK signaling cascade.77 These results confirm that DHA ameliorates cartilage degeneration and may be a potent OA-reducing agent.

The fat-1 transgenic mice (C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-fat-1)1Jxk/J) constitutively express the C. elegans gene fat-1, which encodes a desaturase that converts omega-6 to omega-3 PUFAs. This mouse model provides a unique opportunity to study the role of omega-3 PUFAs in animals without the confounding factors introduced by diet intervention.78 It has been reported that fat-1 mice do not appear to have reduced onset of spontaneous OA compared to wild-type mice;79 however, there was a delayed onset of surgically induced OA with partially downregulated mTOR signaling.80 More recent studies have shown that fat-1 mice fed a high-fat diet rich in omega-6 PUFAs exhibit a significant reduction in OA and synovitis in response to a knee injury in a sex-dependent manner.81

Bone and fatty acids

Bone and energy metabolism

Bone is reported to be the fourth most metabolically active organ, due to the constant production of ATP by osteoblasts and osteoclasts necessary for their proper function.82 Interestingly, bone is also a vital insulin-regulating organ.83 Obesity was initially thought to have a beneficial effect on bone,84, 85 but more recent studies indicate that obesity-related chronic inflammation can have a negative effect on bone biology.86, 87 This is due in part to the association of obesity with high levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which may promote osteoclast activation.88, 89 Adipokines and FAs are now also considered to be important factors regulating bone remodeling in obesity.

Osteoblasts and fatty acids

Osteoblasts are responsible for bone formation; thus, they require a constant energy input for their high cellular metabolic activity. In addition, increased ATP production is necessary during the mineralization process. Although glucose is a vital energy source for osteoblasts, FA β-oxidation is reported to cover 40–80% of their energy requirements.90

Fatty acid receptors in osteoblasts

Similar to chondrocytes, osteoblasts express several intra- and extracellular FA receptors, including PPARs, GPR40,91 GPR120,92 TLR4,93 and CD36.94 PUFA receptors, including GPR40 and GPR120, are shown to have an important effect on osteoblasts and bone. GPR40 activation has a dual effect on osteoblast differentiation. Initially, GPR40 chemical agonists induce early differentiation markers, including alkaline phosphatase (ALP). However, activation of GPR40 at later stages of differentiation lead to the inhibition of the mineralization process.95 Although the knockout of GPR120 does not change bone parameters in ovariectomized mice when compared to wild-type mice,92 the presence of GPR120 in fat-1 transgenic mice is protective for bone loss, indicating that GPR120 plays an important role in sensing PUFA in osteoblasts. TLR4 stimulation has been shown to both suppress96 and promote osteoblastogenesis.97

The lipoprotein receptors have been extensively studied in osteoblasts. CD36 knockout mice exhibited a low bone mass phenotype, as the receptor is mandatory for adequate osteoblast function.98 During osteoblast mineralization, there was a significant upregulation of CD36 mRNA in mice calvarial osteoblasts.99 The role of LDL and LRP receptor family members in osteoblasts has also been investigated.100, 101 For example, FA oxidation in osteoblasts has been shown to be regulated by Wnt-LRP5 signaling. Upon binding to LRP5/6 and Frizzled proteins, Wnt molecules induce an intracellular cascade to stabilize β-catenin in osteoblasts, promoting cell differentiation. Interestingly, mice lacking LRP5 in osteoblasts and osteocytes had dysregulated FA metabolism and an increased adiposity with reduced bone mass when compared with wild-type. Osteoblasts derived from those mice had reduced lipid oxidation, which could be restored by overexpressing Wnt or LRP5.100 These studies suggest that lipid metabolism in osteoblasts is an important modulator of bone formation and homeostasis.

All three main members of the PPAR family have been reported to be expressed in mature osteoblasts.102 Although global knockout of PPARα did not affect bone,103 PPARα stimulation, either by FAs or the artificial agonist benzafibrate, positively influenced osteoblastogenesis and anabolic processes in bone.104 On the other hand, PPARα agonists may induce bone loss by stimulating adipogenesis at the expense of osteoblast formation, eventually leading to inhibition of bone deposition.105 Mice with PPARδ global knockout exhibited smaller body size,106 while PPARδ deletion in all tissues showed a significant reduction in trabecular bone mass compared with wild-type animals.107 Additionally, treatment with the PPARδ agonist GW501516 increased osteoblast differentiation and prevented bone loss in ovariectomized mice.107 Furthermore, PPARδ activation enhanced osteoblastogenesis,104 while PPARδ inhibition resulted in osteopenia. PPARγ, however, is considered pro-catabolic in mature osteoblasts and its activation has been shown to cause bone loss,108 potentially mediated through GPR40 stimulation.109 Furthermore, PPARγ overexpression in osteoblasts decreased bone mineral density (BMD) in male mice and accelerated ovariectomy-induced bone loss in female mice,110 while PPARγ inhibition by its chemical antagonist SR1664 promoted osteogenesis.111

Osteoblasts and SFAs

The effects of SFAs on osteoblasts have been widely investigated, and it is generally agreed that excess SFAs are detrimental to osteoblasts. Palmitic acid was shown to induce apoptosis through the activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) apoptotic pathway. JNK activation mediates cytochrome C release, suggesting that PA induces mitochondrial dysfunction and leads to osteoblast death.112 This FA was also shown to down-regulate SMAD4/5 and RUNX2 signaling, thus inhibiting the mineralization process in osteoblasts.113 PA also increased TLR4 expression in osteoblasts derived from MSCs, implying SFAs are capable of modulating innate immunity in obesity.114 Furthermore, several studies reported a lipotoxic effect of SFA on osteoblasts113, 115 (Fig. 2). Lipotoxicity is a process of lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissue cells. PA-induced lipotoxicity is reported to be the main stimulus for cell apoptosis. Surprisingly, oleic acid was shown to prevent PA-induced lipotoxicity by blocking extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation.116 ERK phosphorylation and NF-κB activation lead to apoptosis, as well as the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-6) by osteoblasts. Additionally, inhibition of intracellular FA synthase in osteoblasts prevents the lipotoxic effect of SFA on those cells.117

Osteoblasts and PUFAs

The role of ARA in osteoblasts is not well understood. ARA has been shown to promote adipogenesis and decrease osteoblastogenesis of MSCs.118 Some studies suggest that ARA inhibits osteoblast differentiation through the cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2)-dependent pathway and an increased expression of COX2 and PGE2.119, 120 Interestingly, omega-3 PUFAs, such as EPA and DHA, did not affect osteoblastogenesis.118 However, DHA was shown to induce the viability of mature osteoblasts, as well as ALP and osteocalcin expression.121 Watkins et al. showed that EPA also increased ALP activity and modulated COX2 expression by reducing PGE2 expression in an osteoblast-like cell line (Fig. 2).121 The effect of ARA on PGE2 expression and ALP activity was, in fact, opposite to that of EPA. It is postulated that ARA and EPA may compete with each other for binding to COX2 during prostaglandin production121. This observation suggests an important role of the omega-6:omega-3 FAs ratio, as COX2 is a rate-limiting enzyme in prostaglandin E2/E3 synthesis. Finally, mice overexpressing the fat-1 gene have increased trabecular bone volume as well as cortical thickness when compared with wild-type littermates,122 indicating the protective effect of omega-3 FAs on bone mass.

Osteoclasts and fatty acids

Osteoclast origin and function

Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells originating from hematopoietic progenitors and are important in the process of bone resorption. Osteoclasts share a common origin with macrophages and are formed through the fusion of progenitor cells. This process requires high energy consumption and an active cell metabolism. Therefore, FA utilization and signaling play crucial roles in osteoclast homeostasis.

Osteoclast activity is precisely regulated by the molecular triad of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL), the signaling receptor for RANKL (RANK), and osteoprotegrin (OPG). RANKL belongs to the TNF superfamily and is a pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by osteoblasts and stromal and immune cells. RANKL can bind to its receptor RANK, located at the cellular membrane of pre-osteoclasts, inducing a cascade of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. In contrast, binding of RANKL to its soluble decoy receptor OPG inhibits bone resorption123.

Fatty acid receptors in osteoclasts

Osteoclasts express FA receptors such as GPR40, −41, −43, and −120,124, 125 TLR4,126 and CD36.127 It was hypothesized that the GPR40 receptor may regulate osteoclast differentiation, after observing bone loss in GPR40 knockout mice.128 This hypothesis was further validated by showing that a GPR40 agonist (GW9508) inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis.129 GPR120 activation negatively regulated osteoclast maturation124 and blocked resorption activity. The SFA receptor TLR4, however, was postulated to positively mediate osteoclastogenesis, PGE2 production, and bone resorption.130

The role of lipoprotein and scavenger receptors in osteoclasts has been widely studied. CD36 and other types of scavenger receptors have been hypothesized to play an important role in the transport and metabolism of cholesterol and estradiol in osteoclasts.94 Furthermore, CD36 has also been shown to facilitate progenitor cell fusion,131 thus mediating the formation of osteoclasts themselves. There is conflicting evidence as to whether a deficiency of LDLR in mice inhibits132 or promotes osteoclastogenesis.133

Osteoclasts also express all three members of the PPAR family: PPARα, PPARδ and PPARγ.102 While the role of PPARα in osteoclasts is not fully understood, in vivo treatment with a PPARα agonist, fenofibrate, as well as synthetic selective PPARα activator, GW9578, decreased osteoclast number.105 Expression of PPARδ is considered to be protective from bone loss, as a PPARδ global knockout exhibited an increase in a number of osteoclasts and bone resorption;107 however, the specific role of PPARδ in those cells has not been well established. Chan et al. activated PPARδ using the specific activator L165041 and showed inhibition of osteoclast formation and bone resorption.134 Finally, PPARγ has been shown to positively regulate osteoclastogenesis in vivo. Mice lacking PPARγ in osteoclasts experienced severe osteopetrosis.135 Furthermore, treatment with thiazolidinediones (TZD) increased osteoclastogenesis as well as the number of circulating osteoclast precursors.136 On the other hand, Chan et al. showed that the PPARγ-specific activator ciglatizone inhibited osteoclast formation and bone resorption. 134 These results suggest the importance of PPAR family in osteoclastogenesis and modulation of bone resorption.

Osteoclasts and SFAs and MUFAs

It has been proposed that PA stimulates osteoclastogenesis via the TLR4/MyD88 and NF-κB pathways, eventually leading to the increased production of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) and osteoclast survival.137 Additionally, another study showed that SFA-enriched, but not MUFA-enriched, meals increased RANKL serum concentration in the postprandial state, implying a potential mechanism by which SFA regulates osteoclast activity.138 It has been demonstrated that PA-induced osteoclastogenesis can be prevented by oleic acid139 through increased FA oxidation and induced expression of CD36 and the diacyloglycerol O-acyltransferase (DGAT1) enzyme.139 The loss of DGAT1, an enzyme facilitating formation of triglycerides, has been shown to induce osteoclastogenesis, suggesting that SFAs can enhance this process.139 On the contrary, long-chain SFAs have been shown to inhibit osteoclastogenesis of bone marrow-derived and RAW 264.7 macrophages125 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, a recent study showed that palmitoleic acid [16:1] (PLA) induced osteoclast apoptosis, decreased resorption markers (i.e., TRAP and MMP-9) and NF-κB activity, and down-regulated MAPK, JNK, and ERK signaling in the RAW 264.7 cell line.140

Osteoclasts and PUFAs

The role of omega-6 FAs and metabolites in osteoclasts remains controversial. Some studies demonstrated that ARA suppressed osteoclastogenesis in human CD14+ monocytes 141 and the RAW 264.7 cell line,142 as well as inhibited formation of osteoclast-like cell lines. However, others reported that ARA and its metabolites, including leukotriene B, appeared to enhance osteoclastogenesis143 (Fig. 2).

The omega-3 PUFAs seem to have an inhibitory effect on osteoclast function. In ovariectomized mice, supplementation with omega-3 PUFAs increased femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) and decreased osteoclast number.144 Furthermore, a diet supplemented with fish oil or omega-3 FAs prevented bone loss during chemotherapy,145 reduced bone resorption markers, and increased bone density in periodontitis.146 Additionally, a maternal diet rich in omega-3 FAs was correlated with a down-regulation of osteoclastogenesis in offspring147 (Fig. 2).

It has been reported that DHA attenuated proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow-derived osteoclasts and promoted apoptosis in mature osteoclasts.148 DHA has also been shown to decrease the production of macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (M-CSF), an important osteoclast survival factor, through the down-regulation of protein kinase B (Akt) activation, which leads to the inhibition of cyclin-1 production,148 as well as inhibition of the NF- κB/RANKL and ERK-JNK-p38 pathways in osteoclasts.141, 148 DHA also has the capacity of inhibiting osteoclastogenesis by the stimulation of lipoxygenase production.149 Furthermore, compared with ARA and LA, DHA and EPA significantly down-regulated osteoclastogenesis and NF-κB signaling in osteoclasts. In another study, DHA was more potent in down-regulating osteoclast differentiation than EPA.150 However, Yuan and colleagues showed that DHA inhibited osteoclastogenesis, while EPA and omega-6 PUFA actually promoted osteoclast differentiation.149 In other studies, Poulsen et al. showed that both DHA and ARA inhibited RANKL-mediated osteoclast formation.151 This finding suggests that PUFA metabolism plays a crucial role in osteoclast development. Interestingly, Oh et al. recently reported that GPR120/βarr2 signaling mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of omega-3 FAs in LPS-stimulated macrophages.25 In this regard, it is possible that macrophages and osteoclasts share similar mechanisms by which omega-3 FAs modulate inflammation, although this hypothesis requires further investigation.

Furthermore, fat-1 transgenic mice were shown to have an attenuated predisposition to rheumatoid arthritis through inhibition of the downstream signaling of the p38 and Janus Kinase/Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling pathway (JAK-STAT3).152 Pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-6, are known stimulators of JAK/STAT3 signaling that triggers osteoclast activity. The fat-1 mice were also reported to have a lower concentration of circulating bone resorption markers.153 These two studies indicate the beneficial role of omega-3 PUFAs in reducing inflammation and maintaining bone quality.

Synovium and fatty acids

Energy metabolism in synovium

The synovium, a heterogeneous tissue encapsulating the articular joints, consists of the synovial membrane with surrounding fibrous and adipose tissue. The synovium plays an important role in maintaining the homeostatic balance in healthy joints by producing synovial fluid, which is necessary for lubrication. In chronic inflammatory synovium, such as in OA and RA, the synovial tissue is highly infiltrated by a variety of immune cells and proliferating synoviocytes. The accumulation of cells greatly increases oxygen consumption, resulting in synovium hypoxia. It has been proposed that oxidative stress due to hypoxic conditions promotes a bioenergetic switch in cell metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation towards aerobic glycolysis (known as the Warburg effect), leading to impaired mitochondria and dysfunctional angiogenesis.154, 155 This hypothesis is also supported by the observation that the synovial fluid of RA patients exhibited up-regulated enzymes of anaerobic catabolism and down-regulated enzymes associated with aerobic oxidation and FA oxidation when compared with healthy individuals.156 Interestingly, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), an oxidation product of PUFAs by reactive oxygen species in hypoxic synovium, may inactivate mitochondrial proteins.157 This result suggests that despite not being used as a primary energy source, FA is an essential contributing factor in inflammatory joint disorders.

Synovium and FA receptors

Although the presence of GPR40 and GPR120 has not been widely investigated in synovial membranes, these FA receptors are expressed in macrophages and adipocytes.158 Furthermore, CD36,159, 160 TLR4,161, 162 and a variety of lipoprotein receptors163, 164 were found to be expressed in the synovial membrane and surrounding tissues. Inhibition of CD36 abrogated PA-induced inflammation67 and TLR4-induced PGE2 and COX2 synthesis in FLS.165 Increased accumulation of LDLs led to synovial activation and osteophyte formation.166

While it is known that all three PPAR receptors are expressed in synovial fibroblasts,167 their role in synovial cells are not completely understood. PPARα activation down-regulated IL-1β-induced inflammatory gene expression in the synovium.167 In accordance, PPARδ stimulation by its agonists increased the expression of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1-Ra), a potent inhibitor of IL-1, in FLS.167 Furthermore, PPARγ is also postulated to have anti-inflammatory effects in the synovium: PPARγ agonists inhibited MMP-1168 as well as TNF-α–mediated MMP-13 expression169 in FLS.

Synovium and FA

It is well-recognized that high-fat feeding promotes the invasion of a variety of immune cells, including macrophages, into the joint synovium. Dietary FAs, particularly SFAs, lead to a phenotypic switch of macrophages toward the M1 pro-inflammatory pathway. Additionally, TNF-α secreted by M1 macrophages can further induce insulin resistance and catabolic processes in chondrocytes, implying a detrimental role of M1 macrophages in OA development.170, 171 Interestingly, we found that conditional depletion of macrophages does not inhibit OA progression in obesity. Rather, this depletion exacerbated synovitis by increasing infiltration of neutrophils and CD3+ T cells.172 Our results emphasize the essential regulatory role of MLS in modulating homeostasis of immune cells in the setting of obesity. A more detailed role of FAs in MLS has been described elsewhere.173, 174

SFAs have also been shown to induce the expression of pro-inflammatory markers such as IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and MMPs in human FLS cell culture.67 Furthermore, FLSs were able to produce both inflammatory and pro-resolving mediators when stimulated with PA. There was a positive association between synovitis and the plasma level of omega-6 PUFAs in patients with OA. In contrast, the plasma level of omega-3 PUFAs was negatively associated with synovitis.175 Mediators derived from omega-6 FAs, including PGE2, have been shown to increase synovial inflammation, while those derived from omega-3 FAs, such as resolvins, were shown to decrease synovial inflammation176, 177 (Fig. 2).

The fat-1 transgenic mice have been shown to have a lower predisposition to RA in a KRN serum transfer mouse model.152 However, metabolic enrichment of omega-3 FAs did not mitigate the joint synovitis of spontaneous OA in fat-1 mice.79

Ligament, meniscus, and fat pads

While this review is focused primarily on cartilage, bone, and synovium, it is important to note that cells in other joint tissues, such as ligaments, meniscus, and infrapatellar fat pad (IPFP), may also be influenced by dietary FAs. There are currently a few studies examining the role of FA metabolism in these tissues. In brief, FA receptors, including TLR4, PPARγ,162 and CD36,160 have been found in IPFP. The presence of FA receptors has not been reported in ligaments or meniscus. However, SFAs have been shown to promote apoptosis in meniscal cells178 by inducing ER stress,179 while omega-3 PUFAs have been postulated to enhance ligament healing.180

Conclusions

Obesity-related complications in the musculoskeletal system have been extensively studied in the past decade. Due to current trends toward increasing obesity caused by unhealthy diets and lifestyles, it is likely that the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders will continue to increase. The studies summarized in this review indicate that dietary FA content can significantly influence tissues and cells within the articular joint. Especially in the context of OA pathogenesis, FAs have been shown to mediate both anabolic and catabolic processes of many joint tissues. In summary, there is strong evidence for the presence and function of both intra- and extracellular receptors for FAs in joint cells, as well as the importance of FA-triggered signals. Although there are still missing links in our understanding of the role of dietary FA content, the current evidence supports a protective role of omega-3 FAs and the pro-inflammatory role of SFAs. Additionally, the literature suggests that a balanced ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 FAs is an important factor in modulating joint homeostasis. The knowledge summarized in this review may trigger new areas of research and future interventions for metabolic joint diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sara Oswald for providing technical writing support for the manuscript. This study was supported in part by NIH Grants AR50245, AR48852, AG15768, AR48182, AG46927, OD10707, DK108742, EB018266, AR073752, the Washington University Musculoskeletal Research Center (NIH P30 AR057235), the Arthritis Foundation, and the Nancy Taylor Foundation for Chronic Diseases. Author contributions: NSH wrote the initial draft; AD, CLW, and FG contributed additional writing and editing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Patterson E, Wall R, Fitzgerald GF, et al. 2012. Health implications of high dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated Fatty acids. Journal of nutrition and metabolism. 2012: 539426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courties A, Sellam J & Berenbaum F 2017. Metabolic syndrome-associated osteoarthritis. Current opinion in rheumatology. 29: 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calder PC 2015. Functional Roles of Fatty Acids and Their Effects on Human Health. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 39: 18s–32s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, et al. 2012. Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis and rheumatism. 64: 1697–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madry H, van Dijk CN & Mueller-Gerbl M 2010. The basic science of the subchondral bone. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 18: 419–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson VL & Hunter DJ 2014. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology. 28: 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burrage PS, Mix KS & Brinckerhoff CE 2006. Matrix metalloproteinases: role in arthritis. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 11: 529–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez-Adams J, Leddy HA, McNulty AL, et al. 2014. The mechanobiology of articular cartilage: bearing the burden of osteoarthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep 16: 451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Hunter D, Xu J, et al. 2015. Metabolic triggered inflammation in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 23: 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin TM, Huebner JL, Kraus VB, et al. 2009. Extreme obesity due to impaired leptin signaling in mice does not cause knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 60: 2935–2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNulty AL, Miller MR, O’Connor SK, et al. 2011. The effects of adipokines on cartilage and meniscus catabolism. Connective tissue research. 52: 523–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu CL, Jain D, McNeill JN, et al. 2015. Dietary fatty acid content regulates wound repair and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis following joint injury. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 74: 2076–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caires R, Sierra-Valdez FJ, Millet JRM, et al. 2017. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Modulate TRPV4 Function through Plasma Membrane Remodeling. Cell reports. 21: 246–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez JC, Lopez-Zapata DF & Wilkins RJ 2014. TRPV4 channels activity in bovine articular chondrocytes: regulation by obesity-associated mediators. Cell calcium. 56: 493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Conor CJ, Griffin TM, Liedtke W, et al. 2013. Increased susceptibility of Trpv4-deficient mice to obesity and obesity-induced osteoarthritis with very high-fat diet. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 72: 300–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, et al. 2013. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. Journal of lipid research. 54: 2325–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancaster GI, Langley KG, Berglund NA, et al. 2018. Evidence that TLR4 Is Not a Receptor for Saturated Fatty Acids but Mediates Lipid-Induced Inflammation by Reprogramming Macrophage Metabolism. Cell metabolism. 27: 1096–1110.e1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saini RK & Keum YS 2018. Omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Dietary sources, metabolism, and significance - A review. Life sciences. 203: 255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohli P & Levy BD 2009. Resolvins and protectins: mediating solutions to inflammation. British journal of pharmacology. 158: 960–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pepino MY, Kuda O, Samovski D, et al. 2014. Structure-function of CD36 and importance of fatty acid signal transduction in fat metabolism. Annual review of nutrition. 34: 281–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glatz JF & Luiken JJ 2017. From fat to FAT (CD36/SR-B2): Understanding the regulation of cellular fatty acid uptake. Biochimie. 136: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jay AG, Chen AN, Paz MA, et al. 2015. CD36 binds oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL) in a mechanism dependent upon fatty acid binding. The Journal of biological chemistry. 290: 4590–4603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara T, Kimura I, Inoue D, et al. 2013. Free fatty acid receptors and their role in regulation of energy metabolism. Reviews of physiology, biochemistry and pharmacology. 164: 77–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JY, Lee HJ, Lee SJ, et al. 2017. Palmitic Acid-BSA enhances Amyloid-beta production through GPR40-mediated dual pathways in neuronal cells: Involvement of the Akt/mTOR/HIF-1alpha and Akt/NF-kappaB pathways. Scientific reports. 7: 4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh DY, Talukdar S, Bae EJ, et al. 2010. GPR120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell. 142: 687–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park BS, Song DH, Kim HM, et al. 2009. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature. 458: 1191–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaeffler A, Gross P, Buettner R, et al. 2009. Fatty acid-induced induction of Toll-like receptor-4/nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in adipocytes links nutritional signalling with innate immunity. Immunology. 126: 233–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grygiel-Gorniak B 2014. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: nutritional and clinical implications--a review. Nutrition journal. 13: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy JK & Hashimoto T 2001. Peroxisomal beta-oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha: an adaptive metabolic system. Annual review of nutrition. 21: 193–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villalvilla A, Gomez R, Largo R, et al. 2013. Lipid transport and metabolism in healthy and osteoarthritic cartilage. International journal of molecular sciences. 14: 20793–20808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damek-Poprawa M, Golub E, Otis L, et al. 2006. Chondrocytes utilize a cholesterol-dependent lipid translocator to externalize phosphatidylserine. Biochemistry. 45: 3325–3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekar S, Shafie SR, Prasadam I, et al. 2017. Saturated fatty acids induce development of both metabolic syndrome and osteoarthritis in rats. Scientific reports. 7: 46457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monfoulet LE, Philippe C, Mercier S, et al. 2015. Deficiency of G-protein coupled receptor 40, a lipid-activated receptor, heightens in vitro- and in vivo-induced murine osteoarthritis. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, N.J.). 240: 854–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Zhang D, Ho KW, et al. 2018. GPR120 is an important inflammatory regulator in the development of osteoarthritis. Arthritis research & therapy. 20: 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sillat T, Barreto G, Clarijs P, et al. 2013. Toll-like receptors in human chondrocytes and osteoarthritic cartilage. Acta orthopaedica. 84: 585–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfander D, Cramer T, Deuerling D, et al. 2000. Expression of thrombospondin-1 and its receptor CD36 in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 59: 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asai N, Ohkawara B, Ito M, et al. 2014. LRP4 induces extracellular matrix productions and facilitates chondrocyte differentiation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 451: 302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto K, Owen K, Parker AE, et al. 2014. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1)-mediated endocytic clearance of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs-4 (ADAMTS-4): functional differences of non-catalytic domains of ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 in LRP1 binding. The Journal of biological chemistry. 289: 6462–6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin Y, Huh YH, Kim K, et al. 2014. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 governs Wnt-mediated osteoarthritic cartilage destruction. Arthritis research & therapy. 16: R37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dehne T, Karlsson C, Ringe J, et al. 2009. Chondrogenic differentiation potential of osteoarthritic chondrocytes and their possible use in matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Arthritis research & therapy. 11: R133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gomez R, Villalvilla A, Largo R, et al. 2015. TLR4 signalling in osteoarthritis--finding targets for candidate DMOADs. Nature reviews. Rheumatology. 11: 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bobacz K, Sunk IG, Hofstaetter JG, et al. 2007. Toll-like receptors and chondrocytes: the lipopolysaccharide-induced decrease in cartilage matrix synthesis is dependent on the presence of toll-like receptor 4 and antagonized by bone morphogenetic protein 7. Arthritis and rheumatism. 56: 1880–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, Joosten LA, Roelofs MF, et al. 2007. Inhibition of Toll-like receptor 4 breaks the inflammatory loop in autoimmune destructive arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 56: 2957–2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu M, Tang D, Wu Q, et al. 2009. Activation of beta-catenin signaling in articular chondrocytes leads to osteoarthritis-like phenotype in adult beta-catenin conditional activation mice. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 24: 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cecil DL, Appleton CT, Polewski MD, et al. 2009. The pattern recognition receptor CD36 is a chondrocyte hypertrophy marker associated with suppression of catabolic responses and promotion of repair responses to inflammatory stimuli. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 182: 5024–5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao YY, Wang L, Hicks DG, et al. 2005. Expression and activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in growth plate chondrocytes. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 23: 1139–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bordji K, Grillasca JP, Gouze JN, et al. 2000. Evidence for the presence of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and gamma and retinoid Z receptor in cartilage. PPARgamma activation modulates the effects of interleukin-1beta on rat chondrocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 275: 12243–12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clockaerts S, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Feijt C, et al. 2011. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha activation decreases inflammatory and destructive responses in osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 19: 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Francois M, Richette P, Tsagris L, et al. 2006. Activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha pathway potentiates interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production in cytokine-treated chondrocytes. Arthritis and rheumatism. 54: 1233–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ratneswaran A, LeBlanc EA, Walser E, et al. 2015. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta promotes the progression of posttraumatic osteoarthritis in a mouse model. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 67: 454–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ratneswaran A, Sun MM, Dupuis H, et al. 2017. Nuclear receptors regulate lipid metabolism and oxidative stress markers in chondrocytes. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany). 95: 431–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francois M, Richette P, Tsagris L, et al. 2004. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma down-regulates chondrocyte matrix metalloproteinase-1 via a novel composite element. The Journal of biological chemistry. 279: 28411–28418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giaginis C, Giagini A & Theocharis S 2009. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) ligands as potential therapeutic agents to treat arthritis. Pharmacological research. 60: 160–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen YJ, Chan DC, Lan KC, et al. 2015. PPARgamma is involved in the hyperglycemia-induced inflammatory responses and collagen degradation in human chondrocytes and diabetic mouse cartilages. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 33: 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monemdjou R, Vasheghani F, Fahmi H, et al. 2012. Association of cartilage-specific deletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma with abnormal endochondral ossification and impaired cartilage growth and development in a murine model. Arthritis and rheumatism. 64: 1551–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasheghani F, Zhang Y, Li YH, et al. 2015. PPARgamma deficiency results in severe, accelerated osteoarthritis associated with aberrant mTOR signalling in the articular cartilage. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 74: 569–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Vasheghani F, Li YH, et al. 2015. Cartilage-specific deletion of mTOR upregulates autophagy and protects mice from osteoarthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 74: 1432–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Afif H, Benderdour M, Mfuna-Endam L, et al. 2007. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma1 expression is diminished in human osteoarthritic cartilage and is downregulated by interleukin-1beta in articular chondrocytes. Arthritis research & therapy. 9: R31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Q, Chen C, Wu S, et al. 2010. Advanced glycation end products downregulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression in cultured rabbit chondrocyte through MAPK pathway. European journal of pharmacology. 649: 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Griffin TM, Fermor B, Huebner JL, et al. 2010. Diet-induced obesity differentially regulates behavioral, biomechanical, and molecular risk factors for osteoarthritis in mice. Arthritis research & therapy. 12: R130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mooney RA, Sampson ER, Lerea J, et al. 2011. High-fat diet accelerates progression of osteoarthritis after meniscal/ligamentous injury. Arthritis research & therapy. 13: R198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Louer CR, Furman BD, Huebner JL, et al. 2012. Diet-induced obesity significantly increases the severity of posttraumatic arthritis in mice. Arthritis and rheumatism. 64: 3220–3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griffin TM, Huebner JL, Kraus VB, et al. 2012. Induction of osteoarthritis and metabolic inflammation by a very high-fat diet in mice: effects of short-term exercise. Arthritis and rheumatism. 64: 443–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu CL, Diekman BO, Jain D, et al. 2013. Diet-induced obesity alters the differentiation potential of stem cells isolated from bone marrow, adipose tissue and infrapatellar fat pad: the effects of free fatty acids. International journal of obesity (2005). 37: 1079–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fu D, Lu J & Yang S 2016. Oleic/Palmitate Induces Apoptosis in Human Articular Chondrocytes via Upregulation of NOX4 Expression and ROS Production. Annals of clinical and laboratory science. 46: 353–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miao H, Chen L, Hao L, et al. 2015. Stearic acid induces proinflammatory cytokine production partly through activation of lactate-HIF1alpha pathway in chondrocytes. Scientific reports. 5: 13092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frommer KW, Schaffler A, Rehart S, et al. 2015. Free fatty acids: potential proinflammatory mediators in rheumatic diseases. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 74: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alvarez-Garcia O, Rogers NH, Smith RG, et al. 2014. Palmitate has proapoptotic and proinflammatory effects on articular cartilage and synergizes with interleukin-1. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 66: 1779–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knott L, Avery NC, Hollander AP, et al. 2011. Regulation of osteoarthritis by omega-3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids in a naturally occurring model of disease. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 19: 1150–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu H, Li Y, Ma L, et al. 2015. A low ratio of n-6/n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids suppresses matrix metalloproteinase 13 expression and reduces adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Nutrition research (New York, N.Y.). 35: 1113–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li TF, Zuscik MJ, Ionescu AM, et al. 2004. PGE2 inhibits chondrocyte differentiation through PKA and PKC signaling. Experimental cell research. 300: 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kojima F, Naraba H, Miyamoto S, et al. 2004. Membrane-associated prostaglandin E synthase-1 is upregulated by proinflammatory cytokines in chondrocytes from patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis research & therapy. 6: R355–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zainal Z, Longman AJ, Hurst S, et al. 2009. Relative efficacies of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in reducing expression of key proteins in a model system for studying osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 17: 896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Curtis CL, Hughes CE, Flannery CR, et al. 2000. n-3 fatty acids specifically modulate catabolic factors involved in articular cartilage degradation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 275: 721–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wann AK, Mistry J, Blain EJ, et al. 2010. Eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid reduce interleukin-1beta-mediated cartilage degradation. Arthritis research & therapy. 12: R207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sakata S, Hayashi S, Fujishiro T, et al. 2015. Oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and matrix loss of chondrocytes is inhibited by eicosapentaenoic acid. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 33: 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Z, Guo A, Ma L, et al. 2016. Docosahexenoic acid treatment ameliorates cartilage degeneration via a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism. International journal of molecular medicine. 37: 1542–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kang JX, Wang J, Wu L, et al. 2004. Transgenic mice: fat-1 mice convert n-6 to n-3 fatty acids. Nature. 427: 504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cai A, Hutchison E, Hudson J, et al. 2014. Metabolic enrichment of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids does not reduce the onset of idiopathic knee osteoarthritis in mice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 22: 1301–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang MJ, Wang L, Jin DD, et al. 2014. Enhancement of the synthesis of n-3 PUFAs in fat-1 transgenic mice inhibits mTORC1 signalling and delays surgically induced osteoarthritis in comparison with wild-type mice. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 73: 1719–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kimmerling KA, W.C.-L., Huebner JL, Little D,Kraus VB,Kang JX, Guilak F 2017. Enrichment Of Endogenous Omega-3 Fatty Acids In Fat-1 Transgenic Mice Attenuates Post-traumatic Arthritis. 2017 ORS abstract 042. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee WC, Guntur AR, Long F, et al. 2017. Energy Metabolism of the Osteoblast: Implications for Osteoporosis. Endocrine reviews. 38: 255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guntur AR & Rosen CJ 2012. Bone as an Endocrine Organ. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 18: 758–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, et al. 1993. Effects of weight and body mass index on bone mineral density in men and women: The framingham study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 8: 567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ribot C, Tremollieres F, Pouilles JM, et al. 1987. Obesity and postmenopausal bone loss: the influence of obesity on vertebral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women. Bone. 8: 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sukumar D, Schlussel Y, Riedt CS, et al. 2011. Obesity alters cortical and trabecular bone density and geometry in women. Osteoporos. Int 22: 635–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ootsuka T, Nakanishi A & Tsukamoto I 2015. Increase in osteoclastogenesis in an obese Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima fatty rat model. Molecular medicine reports. 12: 3874–3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cao JJ, Sun L & Gao H 2010. Diet-induced obesity alters bone remodeling leading to decreased femoral trabecular bone mass in mice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1192: 292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hofbauer LC, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, et al. 1999. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, but not interleukin-6, stimulate osteoprotegerin ligand gene expression in human osteoblastic cells. Bone. 25: 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim SP, Li Z, Zoch ML, et al. 2017. Fatty acid oxidation by the osteoblast is required for normal bone acquisition in a sex- and diet-dependent manner. JCI insight. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mieczkowska A, Basle MF, Chappard D, et al. 2012. Thiazolidinediones induce osteocyte apoptosis by a G protein-coupled receptor 40-dependent mechanism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 287: 23517–23526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ahn SH, Park SY, Baek JE, et al. 2016. Free Fatty Acid Receptor 4 (GPR120) Stimulates Bone Formation and Suppresses Bone Resorption in the Presence of Elevated n-3 Fatty Acid Levels. Endocrinology. 157: 2621–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kikuchi T, Matsuguchi T, Tsuboi N, et al. 2001. Gene expression of osteoclast differentiation factor is induced by lipopolysaccharide in mouse osteoblasts via Toll-like receptors. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 166: 3574–3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brodeur MR, Brissette L, Falstrault L, et al. 2008. Scavenger receptor of class B expressed by osteoblastic cells are implicated in the uptake of cholesteryl ester and estradiol from LDL and HDL3. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 23: 326–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Philippe C, Wauquier F, Lyan B, et al. 2016. GPR40, a free fatty acid receptor, differentially impacts osteoblast behavior depending on differentiation stage and environment. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 412: 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li MJ, Li F, Xu J, et al. 2016. rhHMGB1 drives osteoblast migration in a TLR2/TLR4- and NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Bioscience reports. 36: e00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.He X, Wang H, Jin T, et al. 2016. TLR4 Activation Promotes Bone Marrow MSC Proliferation and Osteogenic Differentiation via Wnt3a and Wnt5a Signaling. PloS one. 11: e0149876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kevorkova O, Martineau C, Martin-Falstrault L, et al. 2013. Low-bone-mass phenotype of deficient mice for the cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36). PloS one. 8: e77701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Staines KA, Zhu D, Farquharson C, et al. 2014. Identification of novel regulators of osteoblast matrix mineralization by time series transcriptional profiling. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 32: 240–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Frey JL, Li Z, Ellis JM, et al. 2015. Wnt-Lrp5 signaling regulates fatty acid metabolism in the osteoblast. Molecular and cellular biology. 35: 1979–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Niemeier A, Kassem M, Toedter K, et al. 2005. Expression of LRP1 by human osteoblasts: a mechanism for the delivery of lipoproteins and vitamin K1 to bone. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 20: 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Giaginis C, Tsantili-Kakoulidou A & Theocharis S 2007. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the control of bone metabolism. Fundamental & clinical pharmacology. 21: 231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee SS, Pineau T, Drago J, et al. 1995. Targeted disruption of the alpha isoform of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Molecular and cellular biology. 15: 3012–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Still K, Grabowski P, Mackie I, et al. 2008. The peroxisome proliferator activator receptor alpha/delta agonists linoleic acid and bezafibrate upregulate osteoblast differentiation and induce periosteal bone formation in vivo. Calcified tissue international. 83: 285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Patel JJ, Butters OR & Arnett TR 2014. PPAR agonists stimulate adipogenesis at the expense of osteoblast differentiation while inhibiting osteoclast formation and activity. Cell biochemistry and function. 32: 368–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Peters JM, Lee SS, Li W, et al. 2000. Growth, adipose, brain, and skin alterations resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta(delta). Molecular and cellular biology. 20: 5119–5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Scholtysek C, Katzenbeisser J, Fu H, et al. 2013. PPARbeta/delta governs Wnt signaling and bone turnover. Nature medicine. 19: 608–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Harslof T, Wamberg L, Moller L, et al. 2011. Rosiglitazone decreases bone mass and bone marrow fat. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 96: 1541–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tang XL, Wang CN, Zhu XY, et al. 2015. Rosiglitazone inhibition of calvaria-derived osteoblast differentiation is through both of PPARgamma and GPR40 and GSK3beta-dependent pathway. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 413: 78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cho SW, Yang JY, Her SJ, et al. 2011. Osteoblast-targeted overexpression of PPARgamma inhibited bone mass gain in male mice and accelerated ovariectomy-induced bone loss in female mice. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 26: 1939–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Marciano DP, Kuruvilla DS, Boregowda SV, et al. 2015. Pharmacological repression of PPARgamma promotes osteogenesis. Nature communications. 6: 7443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gunaratnam K, Vidal C, Boadle R, et al. 2013. Mechanisms of palmitate-induced cell death in human osteoblasts. Biology open. 2: 1382–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yeh LC, Ford JJ, Lee JC, et al. 2014. Palmitate attenuates osteoblast differentiation of fetal rat calvarial cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 450: 777–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Alsahli A, Kiefhaber K, Gold T, et al. 2016. Palmitic Acid Reduces Circulating Bone Formation Markers in Obese Animals and Impairs Osteoblast Activity via C16-Ceramide Accumulation. Calcified tissue international. 98: 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jing L & Jia XW 2018. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide arbitrates palmitate-induced apoptosis in MC3T3E1 cells through decreasing the activation of ERSmediated apoptosis pathway. Molecular medicine reports. 17: 2415–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gillet C, Spruyt D, Rigutto S, et al. 2015. Oleate Abrogates Palmitate-Induced Lipotoxicity and Proinflammatory Response in Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Osteoblastic Cells. Endocrinology. 156: 4081–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Elbaz A, Wu X, Rivas D, et al. 2010. Inhibition of fatty acid biosynthesis prevents adipocyte lipotoxicity on human osteoblasts in vitro. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 14: 982–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Casado-Diaz A, Santiago-Mora R, Dorado G, et al. 2013. The omega-6 arachidonic fatty acid, but not the omega-3 fatty acids, inhibits osteoblastogenesis and induces adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells: potential implication in osteoporosis. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 24: 1647–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yoshida K, Shinohara H, Haneji T, et al. 2007. Arachidonic acid inhibits osteoblast differentiation through cytosolic phospholipase A2-dependent pathway. Oral diseases. 13: 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Coetzee M, Haag M, Joubert AM, et al. 2007. Effects of arachidonic acid, docosahexaenoic acid and prostaglandin E(2) on cell proliferation and morphology of MG-63 and MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids. 76: 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Watkins BA, Li Y, Lippman HE, et al. 2003. Modulatory effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on osteoblast function and bone metabolism. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids. 68: 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Koren N, Simsa-Maziel S, Shahar R, et al. 2014. Exposure to omega-3 fatty acids at early age accelerate bone growth and improve bone quality. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 25: 623–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]