Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to evaluate the regulation of miR-99a to the biological functions of granulosa cells in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) via targeting IGF-1R.

Methods

We collected aspirated follicular fluid in both patients with and without PCOS. Granulosa cells (GCs) were isolated through Percoll differential centrifugation to detect both miR-99a and IGF-1R expressions. We further transfected COV434 cells with miR-99a mimics to establish a miRNA-99a (miR-99a) overexpression model. We explored the regulation of miR-99a to the proliferation and apoptosis of human GCs via IGF-1R in COV434. The effect of different insulin concentrations on miR-99a expression was also evaluated.

Results

MiR-99a was significantly downregulated while IGF-1R was upregulated in patients with PCOS. MiR-99a can regulate IGF-1R on a post-transcriptional level. After transfection of miR-99a mimics, the proliferation rate was decreased and apoptosis rate was increased significantly in COV434. Exogenous insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) treatment could reverse the effect of miR-99a. MiR-99a was negatively and dose-dependently regulated by insulin in vitro.

Conclusions

MiR-99a expression was downregulated in patients with PCOS, the degree of which may be closely related to insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. MiR-99a could attenuate proliferation and promote apoptosis of human GCs through targeting IGF-1R, which could partly explain the abnormal folliculogenesis in PCOS.

Keywords: miR-99a, Granulosa cell, IGF-1R, Proliferation, Apoptosis, Polycystic ovary syndrome

Introduction

MiRNAs are a group of single-chain non-coded small RNAs consisting of 19–25 nucleotides. MiRNAs are transcribed into hairpin structure relying on RNA polymerase II, and then processed to long miRNA precursor by RNA enzyme II Dorsha. The precursors are transferred to cytoplasm, recognized and cut to mature miRNAs by RNA enzyme III Dicer [1]. By targeting the 3′ non-coded region, miRNAs inhibit translation of target mRNAs or promote their degradation via RNA interference [2, 3]. MiRNAs can be functionally classified to proto-oncogene or tumor suppressors, which plays an important part in gene expression regulation [2]. Thirty percent of genes in humans could act as the targets of miRNAs to regulate the downstream signaling pathways and a variety of biological behaviors including proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion [4–6].

MiR-99a belongs to the miR-99a family, which embodies another two members, miR-99b and miR-100. It is located on chromosome 21q21.1, the intron 13 of the C21orf34 gene region. MiR-99a has been detected to decrease in multiple tumor tissues including ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and cervical cancer [7]. MiR-99a could target the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of many genes such as IGF-1R, AKT1, mTOR, HOXA1, NOX4, and TNFAIP8 to inhibit their expressions, which is involved in the tumor migration process [8–10].

IGF-1R belongs to the transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor family. It is a heterodimer composed of α and β chains, and activated by insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) or IGF-2. The combination of IGF-1 to IGF-1R could activate tyrosine kinase and regulate downstream pathways including Ras/Raf/Mek/Erk, PI3K/AKT, and mTOR, which is involved in cell metabolism and growth [11].

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complicated endocrine metabolic disorder of high heterogeneity, with an occurrence of 5–10% in fertile women [12]. PCOS is characterized with chronic ovulation disorder, hyperandrogenemia, and bilateral polycystic ovaries, often accompanied by insulin resistance, menstrual disorder, hirsutism, acne, and obesity [13, 14]. The pathology of PCOS is considered to be related both to genetic and environmental factors, which is still not clearly elucidated [15]. In early folliculogenesis, the relatively lower apoptosis rate and higher proliferation rate than normal in PCOS are accounted for simultaneous development of a large number of follicles. In addition, slow growth of antral follicles leads to a prolonged proliferative period while delayed atresia, causing accumulation of growing follicles in a period [15]. However, development beyond the mid-antral stage is different as the follicles begin to exhibit the tendency of atresia and degeneration. There is progressive accumulation of follicular fluid and expansion of the antrum. As the follicle enlarges, the granulosa cell (GC) layer undergoes apoptosis. Eventually, the follicle wall may become devoid of GCs, leading to the appearance of a thin-walled cyst [16–19]. The apoptosis of GCs could lead to follicular atresia. Therefore, the abnormal folliculogenesis in a patient with PCOS may be associated with dysfunction of ovarian GCs.

A study has demonstrated that compared to slightly-atretic and healthy-developed follicles, estrogen level and IGF-1/IGF-1R expression significantly decreased, while the percentage of GC apoptosis increased in totally-atretic follicles [20]. Cakir et al. discovered in a case-control study that IGF-1 expression in patients with PCOS was remarkably increased, and the result also applied to the patients with HOMA-IR beyond 2.7. To explain this, IGF-1 and its receptors could play an important role in the pathology of PCOS [20, 21].

Hossain et al. reported 24% differentially expressed miRNAs from control in a 5α-DTH induced PCOS rat model [22]. Roth et al. reported 29 differentially expressed miRNAs in the follicular fluid of patients with PCOS compared to a normal group [23]. The role of miRNAs in GC growth and oocyte development has gained more and more attention. Actually, even the change of one single miRNA could exert adverse effect on cytological behaviors and oocyte development, since miRNA-related target genes could be crucial points in signaling pathways like lipid metabolism, insulin signal transduction, and oocyte maturation. Of note, all these courses are closely related to PCOS [24]. For this reason, we deduced that the change of miRNA expression pattern could bring about follicular growth retardation and metabolic disorder in PCOS.

Materials and methods

Participants

All patients (aged 20–35 years, body mass index (BMI) 18–25 kg/m2, basal follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) < 10 IU/L) underwent IVF/ET due to male factor infertility or tubal factor infertility. All participants were collected from the Reproductive Center of Tongji Hospital during the period from June 2016 to October 2016. The experimental group included 15 married women with PCOS. The control group comprised 15 women without PCOS. The diagnosis of PCOS was made according to the Rotterdam consensus [12]. In this study, all the participants have absence of abnormal ovarian (except PCOS) or/and endometrial ultrasonographic features. Patients with clinically significant systemic disease such as neoplastic disease, diabetes, and uncontrolled hypothyroidism as well as serious medical and surgical disease complications were excluded.

Stimulation protocol

Stimulation with recombinant FSH (Gonal-F; Merck Serono S.A., Coinsins, Switzerland) was initiated on days 2–3 of the menstrual cycle until the induction of ovulation. During the stimulation, recombinant FSH doses were adjusted in accordance with the ovarian response evaluated by transvaginal ultrasonography. The women received 0.25 mg of GnRH antagonist (Cetrotide; Merck Serono, Darmstadt, Germany) daily until induction of ovulation on days 5–6 of COH. When three follicles reached a mean diameter of 17 mm, or two follicles reached a mean diameter of 18 mm, 0.2 mg of recombinant luteinizing hormone (Ovidrel; Merck Serono) was administered intramuscularly. Oocyte retrieval was performed by transvaginal ultrasonography-guided single-lumen needle aspiration 36 h after luteinizing hormone injection. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) was only performed for patients experiencing severe male factor infertility. Luteal phase support was initiated on the day of oocyte retrieval.

Granulosa cell isolation

The GCs were collected by the Percoll differential centrifugation method. In brief, the aspirated follicular fluid was centrifuged at 2000g for 10 min after the removal of oocytes. Then, cell pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), gently layered on a 50% Percoll gradient, and centrifuged at 3000g for 20 min. The gray GC layer at the interface was collected and washed a few times with PBS. Next, red blood cell lysis buffer was added to remove red blood cells. The purified isolated GCs were applied to the following experiment or stored in − 80 °C.

Cell culture

Human granulosa-like tumor cell line COV434 (Procell, Wuhan, China) was cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F-12 medium (Hyclone, USA) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone) and 1% penicillin G/streptomycin sulfate (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). The cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

MiR-99a mimics transfection and exogenous IGF-1 recovery

The miRNA-99a mimics and corresponding negative control (NC) were synthesized by Genecopoeia (MD, USA). Human recombinant insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) was synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and was beforehand diluted to 5 ng/μl according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Cells were seeded onto six-well plates at 3 × 105/ml/well. After incubating for 24 h, cells were transfected using transfection reagent and transfection buffer from Genecopoeia (MD, USA) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Twenty-four hours after transfection, 20 μl exogenous IGF-1 was added to corresponding wells to make the final IGF-1 concentration 100 ng/ml, and 20 μl sterilized saline was added to the NC and transfection-only wells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were collected for AnnexinV-FITC/PI cell apoptosis detection, Western blot, or quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR) analyses.

Insulin stimulation

Recombinant human insulin was synthesized by Novo nordisk (Denmark). It was diluted to 4 μg/μl beforehand according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Zero, 10, 20, and 40μl diluted insulin were added to corresponding wells respectively to establish an insulin concentration from 0 to 160 μg/ml. Extra sterilized saline was added to make the total liquid 40 μl/well. After 24 h, cells were collected for Western blot or QRT-PCR.

Cell counting kit-8 assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using the CCK-8 method. Cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at 4000 cells/100 μL/well. All cells were cultured and intervened as introduced above. From 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after transfection, cck-8 assay was conducted, respectively. In brief, 10 μl CCK-8 solution was added to each well according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After incubating for 2 h, the absorbance was read at 450 nm. This assay was performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

AnnexinV-FITC/PI cell apoptosis detection

Cell apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry using the AnnexinV-FITC/PI cell apoptosis detection kit according to the protocol of the manufacturer (BD Biosciences, NJ, USA). In brief, cells were harvested and washed with PBS at 4 °C. Next, cells were resuspended in 200 μL of binding buffer and incubated with 10 μL of Annexin V-FITC solution (15 min, room temperature) in the dark. Then, cells were incubated with 10 μL PI and 300 μL binding buffer and immediately analyzed in flow cytometer to separate living cells, apoptotic cells, and necrotic cells. This assay was repeated three times.

Western blotting

Total protein of isolated GCs or adherent cells was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer, and protein concentration was quantified with the BCA protein determination method. Equal amounts (60 μg) of protein samples were electrophoresed in sodium dodecyl sulfonate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Then, the membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk and incubated overnight at 4 °C with specific rabbit anti-human primary antibodies (1:10000 dilution for IGF-1R monoclonal antibody from Abcam (#172965), Cambridgeshire, UA; 1:1000 dilution for pIGF-1R monoclonal antibody from Cell Signaling (#80732), Beverly, MA; 1:2000 dilution for GAPDH polyclonal antibody from Serviobio (#11002), Wuhan, China). Next, these blots were incubated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (1:10000 dilution, Serviobio (#23303), Wuhan, China) for 1 h at 37 °C, and detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Advansta, USA). The gray numerical value of protein fragments was semi-quantified using ImageJ v1.8.0. This experiment was repeated three times.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

The primer of miR-99a and U6 small nuclear RNA was synthesized by Genecopoeia (MA, USA). The primer for IGF-1R and GAPDH was synthesized by Tsingke (Wuhan, China). The primer sequence was showed in Table 1. Total RNA of isolated GCs or adherent cells was extracted using Nucleozol (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Reverse transcription and qPCR were performed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit and SYBR qPCR Mix kit according to the protocols of the manufacturer (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The miRNA expression was performed using the All-in-one miRNA qRT-PCR detection kit (Genecopoeia, MA, USA). The RT conditions for miRNAs were as follows, 37 °C for 60 min, 85 °C for 300 s, and 37 °C for 30 s. The qPCR conditions for miRNAs were as follows, 95 °C for 600 s (1 cycle), 95 °C for 10 s, 58°C for 20 s, 72 °C for 10 s (40 cycles), 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 60 s, and 95 °C for 1 s (1 cycle). Relative expression was normalized to an internal control (GAPDH for IGF-1R or U6 small nuclear RNA for miR-99a expression). All the reactions were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. Data were analyzed using the 2-δδCt method.

Table 1.

Primer sequences (5′–3′) used in QRT-PCR

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS v19.0 software. For comparison, differences between groups were tested with Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA. Bilateral P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

The basic clinical characteristics of PCOS and non-PCOS participants

Age; BMI; duration of infertility; basal FSH, luteinizing hormone (LH) and anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels; and the number of antral follicles (AFC) were compared between 15 women with PCOS and 15 women without PCOS. As the results presented in Table 2 show, differences between age, BMI, duration of infertility, and basal FSH were not significant, while patients with PCOS were found to possess higher LH level (11.52 vs.6.71,P < 0.01), AMH level (12.22 vs.4.57, P < 0.01, as well as AFC (26.54 vs.15.67, P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of 30 patients with or without PCOS

| Characteristics | Non-PCOS | PCOS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 28.53 ± 1.85 | 27.23 ± 1.83 | 0.073 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.79 ± 2.13 | 22.17 ± 2.04 | 0.637 |

| Infertility duration (year) | 3.73 ± 1.53 | 3.54 ± 1.66 | 0.750 |

| Basal FSH (IU/L) | 5.44 ± 1.56 | 6.19 ± 1.38 | 0.194 |

| Basal LH (IU/L) | 6.71 ± 1.21 | 11.52 ± 3.52 | < 0.01 |

| Basal AMH (ng/ml) | 4.57 ± 1.93 | 12.22 ± 4.37 | < 0.01 |

| AFC (n) | 15.67 ± 4.76 | 26.54 ± 8.58 | < 0.01 |

BMI body mass index, FSH follicle stimulating hormone, LH luteinizing hormone, AMH anti-Mullerian hormone, AFC antral follicle count

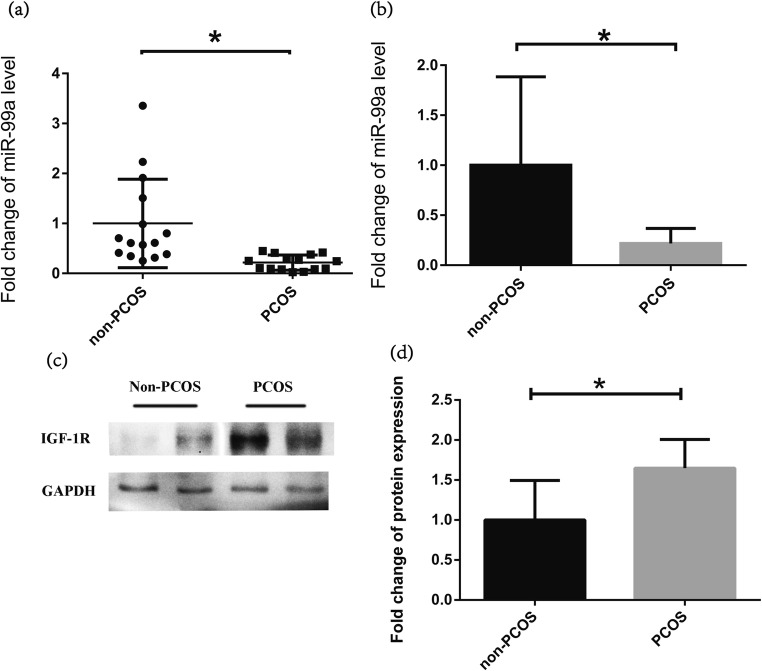

MiR-99a expression is downregulated and IGF-1R is upregulated in isolated human GCs from PCOS

miR-99a expression was examined by qRT-PCR in isolated human GCs from the aspirated follicular fluid of 15 women with and 15 women without PCOS. Although overlap and dispersibility of miR-99a level distribution existed between PCOS and non-PCOS (Fig. 1a), the overall expression of miR-99a in PCOS patients was still significantly lower than that in non-PCOS (Fig. 1b). However, the protein level of IGF-1R was significantly higher in the PCOS group than that in the non-PCOS group (Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1.

The expression level of miR-99a is downregulated while IGF-1R protein is upregulated in human granulosa cells (GCs) from polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). a, b The expression levels of miR-99a were examined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR) in isolated human GCs from the aspirated follicular fluid in women with PCOS (15 cases) and women without PCOS (non-PCOS: 15 cases). c The representative bands of IGF-1R protein examined by Western blot in isolated human GCs from the aspirated follicular fluid in women with PCOS (15 cases) and women without PCOS (non-PCOS: 15 cases). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was served as control. d Quantification of IGF-1R protein using the ImageJ software after normalization with GAPDH. *P < 0 .05 vs. non-PCOS

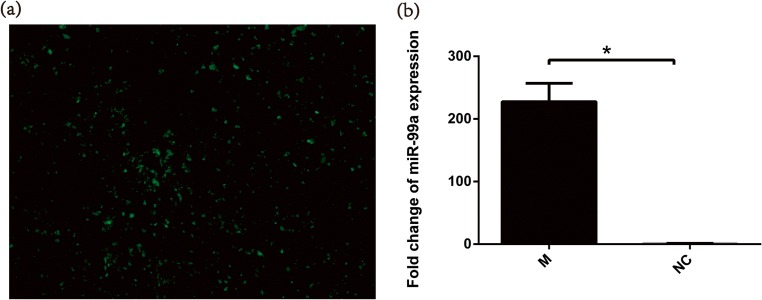

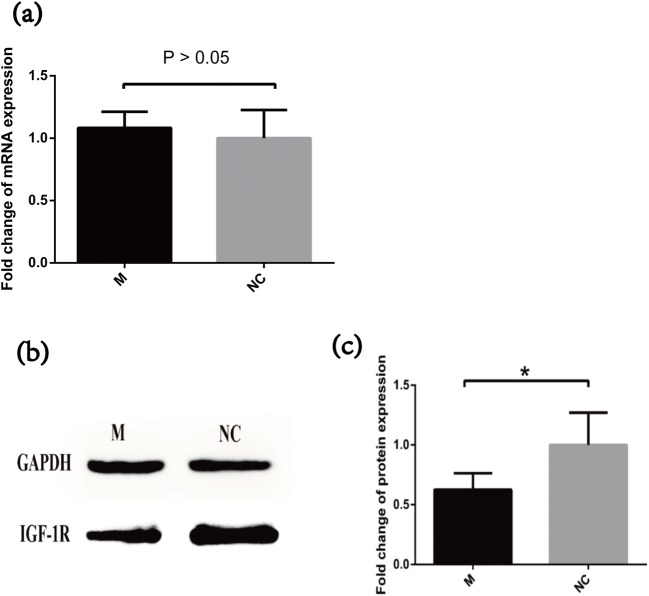

Overexpression of miR-99a does not influence IGF-1R mRNA expression, while it downregulates IGF-1R protein expression

According to the known dual luciferase report [25], miR-99a could target the 3’-UTR of IGF-1R. To evaluate the relationship between miR-99a and IGF-1R, we transfected miR-99a mimics and NC respectively to an in vitro granulosa cell line COV434. Fluorescent signal detection was shown with green fluorescence indicating successfully transfected cells (Fig. 2a). QRT-PCR further verified that miR-99a was almost 228 times higher in the miR-99a-transfected group than in the NC group (Fig. 2b). Comparing the IGF-1R expression between transfection and control groups, IGF-1R mRNA showed no difference between the two groups (Fig. 3a). However, 0.63 times lower IGF-1R protein level was shown in miR-99a-transfected cells (Fig. 3b, c).

Fig. 2.

The expression level of miR-99a is significantly inhibited in COV434 after miR-99a mimics transfection. a Transfected COV434 observed through fluorescence microscope marked by green fluorescence. b The relative expressions of miR-99a at the mRNA level were analyzed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR) after transfection of mimics or negative control; *P < 0.05 vs. control. M miR-99a mimics, NC negative control

Fig. 3.

The expression level of IGF-1R protein but not mRNA is increased after miR-99a mimics transfection. a The relative expressions of IGF-1R at the mRNA level were analyzed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR) after transfection of mimics or negative control. b The expression levels of IGF-1R protein were determined by Western blot. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was served as control. c Quantification of IGF-1R protein using the ImageJ software after normalization with GAPDH. *P < 0.05 compared vs. control. M miR-99a mimics, NC negative control

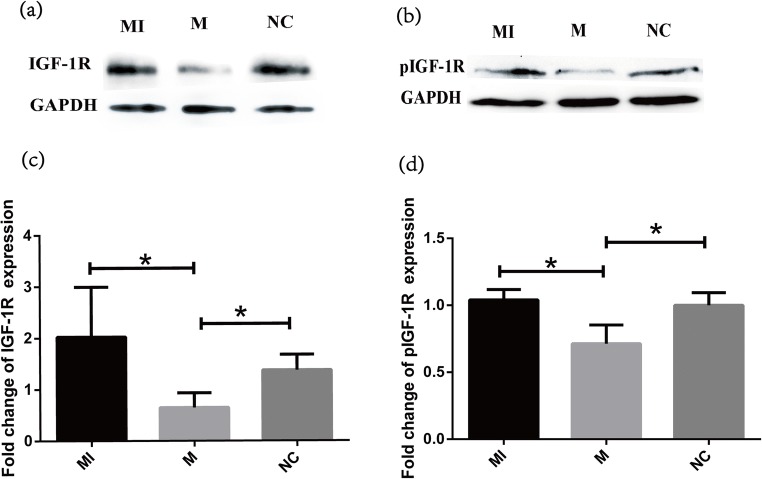

Overexpression of miR-99a inhibits both the IGF-1R and pIGF-1R protein expressions

To evaluate whether miR-99a could regulate and affect the function of IGF-1R in GCs, we detected both IGF-1R and pIGF-1R expression in COV434. Forty-eight hours after miR-99a transfection, IGF-1R and pIGF-1R protein expressions both decreased remarkably; however, treatment of IGF-1 after transfection could significantly reverse the effect of miR-99a. IGF-1R and pIGF-1R expression gained back to normal level again (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

MiR-99a inhibits the expression levels of pIGF-1R and IGF-1R proteins in COV434. a, b The expression levels of pIGF-1R and IGF-1R proteins were determined by Western blot, respectively. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was served as control. c, d IGF-1R and pIGF-1R protein levels were quantified respectively using the ImageJ software after normalization with GAPDH. *P < 0.05 vs. control. MI IGF-1 addition after mimics transfection, M miR-99a mimics, NC negative control

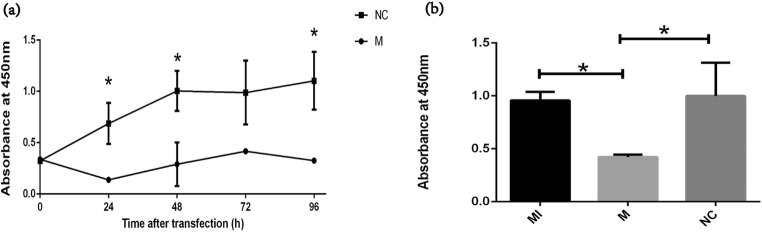

Overexpression of miR-99a suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis of GCs

The effect of miR-99a on cell proliferation was evaluated using CCK-8. As shown in Fig. 5, after 24 h of transfection, cell proliferation was sharply inhibited in the miR-99a-transfected group than in the NC-transfected group. During the following 72 h, the cell proliferation of the miR-99a-transfected group began to increase slowly while kept lower than the NC group (Fig. 5a). We further chose to add IGF-1 at 24 h after miR-99a transfection, and compared cell proliferation at 24 h after IGF-1 addition. As Fig. 5b showed, the cell proliferation after IGF-1 addition could increase to nearly the same level as that in the control group or even higher.

Fig. 5.

MiR-99a inhibits the proliferation of COV434. a The CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate the effect of miR-99a on COV434 proliferation during 96 h after transfection. b The CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate the inhibitory effect of miR-99a on COV434 proliferation with or without IGF-1 addition. *P < 0.05 vs. control. MI IGF-1 addition after mimics transfection, M miR-99a mimics, NC negative control

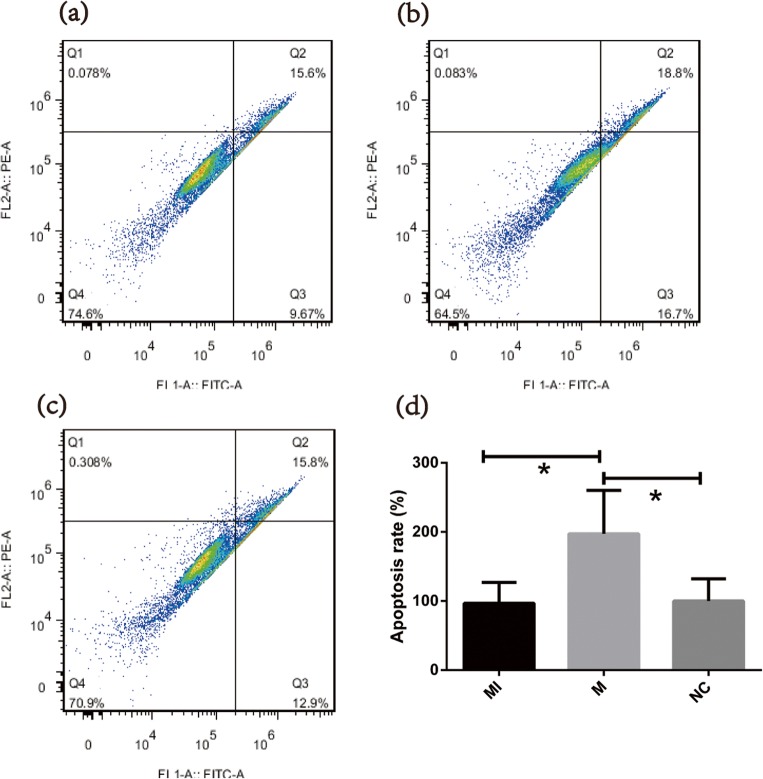

The effect of miR-99a on cell apoptosis was evaluated using the Annexin-FITC/PI double staining method. As presented in Fig. 6, 48 h after miR-99a transfection (24 h after IGF-1 addition), the apoptosis rate of the transfection group was significantly higher than the other two. The apoptosis rate of the IGF-1-treated group was almost the same as that in the control group and the difference showed no significance.

Fig. 6.

MiR-99a promotes the apoptosis of COV434. a–c Representative flow charts of cell apoptosis by the Annexin5-FITC/PI double staining method for the MI/M/NC group, respectively. d Quantification of apoptosis rates (Q2 + Q3) for the MI/M/NC group, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs. control; MI IGF-1 addition after mimics transfection, M miR-99a mimics, NC negative control

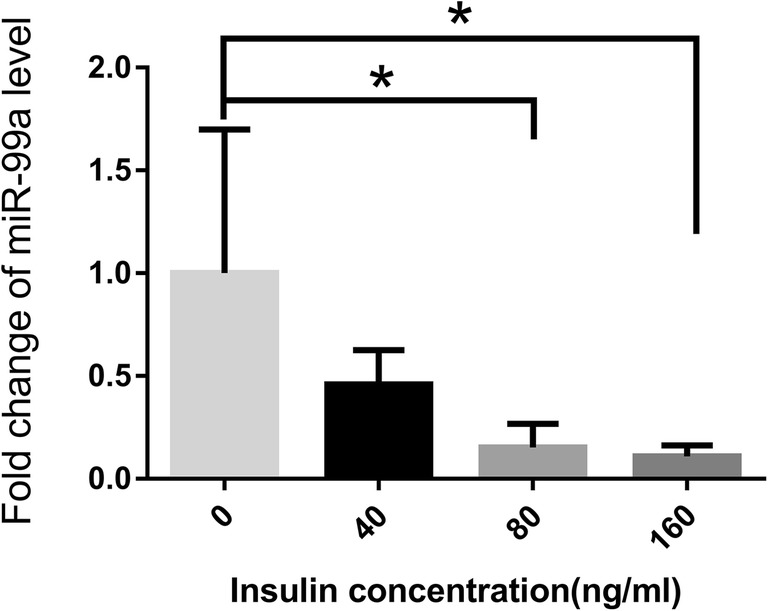

Insulin inhibits miR-99a expression in a dose-dependent manner

By exerting a gradient concentration of insulin on COV434, miR-99a level was detected 24 h after incubation (Fig. 7). As exogenous insulin increased from 0 to 160 ng/ml, miR-99a expression gradually decreased, and insulin showed the greatest effect at 80–160 ng/ml (P < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Insulin inhibits miR-99a expression in COV434. The expression levels of miR-99a were examined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR) in COV434 treated with different concentrations of insulin. *P < 0.05 vs. 0 ng/mL insulin

Discussion

As is well-known that the biological function disorder of GCs is dominant in PCOS pathology, thus the close relationship between miR-99a and PCOS is noted. Our study in clinical samples also detected significantly lower expression of miR-99a and higher IGF-1R protein level in women with PCOS. To evaluate the underlying relationship between miR-99a and IGF-1R expression, we transfected the in vitro COV434 cell line with miR-99a mimics and corresponding negative control, respectively. Of note, transfected cells with miR-99a overexpression showed significantly lower IGF-1R protein expression than the control group, while no obvious difference of IGF-1R mRNA level was found. The result indicated that the regulation of miR-99a to IGF-1R was after transcription rather than on the transcriptional level. To further explore whether miR-99a could definitely target IGF-1R and regulate its function towards biological behaviors of GCs, we compared IGF-1R/pIGF-1R protein expression, cell proliferation, and apoptosis rate of GCs respectively in the control group, miR-99a-transfected group, and transfection followed by IGF-1 addition group. As the results displayed, transfection of miR-99a could negatively regulate IGF-1R/pIGF-1R protein level to attenuate proliferation and accelerate apoptosis of GCs. Considering that insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia is ubiquitous and well characterized in PCOS patients, we further probed into the effect of insulin concentration on miR-99a expression. The result showed that insulin could lower miR-99a expression in a dose-dependent manner, especially at a level beyond 80 ng/ml. We deduced that the hyperphysiological dose of insulin in patients with PCOS may be one of the reasons for lowered miR-99a level in GCs.

Changes of miRNA expression were reported to well indicate disturbed homeostasis. Genetic array has proved that miR-99a is decreased in many types of tumor samples such as oral/head and neck carcinoma, and the decrease tends to be sharper as tumor stage proceeds [7]. Meanwhile, MiR-99a has been associated with various inflammatory and disease processes. For example, it could act as a biological indicator of acute immune rejection in patients with renal transplantation [26] or as a marker of acute myocardial infarction [27]. The miR-99 family can also regulate the expression of target genes IGF-1R, mTOR, and AKT1 and participate in the repair of skin injury [28]. The role of miRNAs in the mammalian reproductive system has been widely studied. MiR-29a, miR-30d, and miR-224 were reported to be associated with the development of follicles in mice [29]. The key enzyme Dicer in miRNA synthesis was expressed in both oocytes and GCs in mice. With Dicer1 knockout, the mobilization of the primordial follicle pool and the accumulation of early follicles were accelerated. Meanwhile, atretic and degenerated follicles significantly increased. In addition, when comparing Dicer1 knockout mice and wild mice of important follicular development related genes, such as AMH, GDF9, and CYP19A1, obvious differences were detected. Therefore, miRNAs play a key role in follicle growth and development [30, 31]. We in our study detected lower miR-99a level in PCOS and verified its function in follicle development via the downstream IGF-1 receptor. Our result was consistent with several studies detecting differences of many other miRNAs in follicular fluid or blood circulation in patients with PCOS [23, 32]. By graphing the expression spectrum of miRNA in cumulus cells of patients with PCOS, 10 types of miRNAs increased, while the other 7 decreased. These altered miRNAs could target numerous genes to play different functions, regulating the signaling pathways of Wnt-, MAPK-, and PI3k/AKT to participate in the oocyte meiosis, progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation, proliferation of GCs, and other aspects [24].

Previous studies have proved that miR-145, miR-592, miR-133, miR-7, and miR375 could all target IGF-1R to regulate downstream PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and other pathways [33]. We proved that IGF-1R was a candidate target of miR-99a through the result of dual luciferase assay performed before [25]. Activation of IGF-1R can directly affect cell proliferation and apoptosis via regulation of the downstream signaling pathway or expression of related genes and factors such as GDF-9 and BMP-6 during follicular development and hormone production in PCOS [34]. The regulation of IGF-1R was found to be associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, aging, and a range of tumors. In our study, we focused more on the effect of IGF-1R on proliferation and apoptosis of GCs, which is important in abnormal folliculogenesis of PCOS. In fact, activated IGF-1R can further activate tyrosine kinase, inducing phosphorylation of the IRS protein family as well as the PI3- and MAPK- activation, so as to upregulate cell cycle protein (cyclin) D1, to induce Rb protein phosphorylation and to activate downstream target genes. Activated IRS protein can act on Ras/Raf/Mek/Erk and PI3K/AKT pathways. The former regulates insulin and IGFs-related mitosis promotion process, and the latter regulates a variety of key enzymes and cell metabolism via sugar intake, protein and lipid synthesis. At the same time, the phosphorylated IGF-1R can also activate the downstream p70S6K and 4e-bp1 molecules through the mTOR pathway, and promote synthesis of periodic proteins such as cyclin D1, cyclin D3, and cyclin E. In addition, activation of IGF-1R can reduce cell cycle inhibitors such as PTEN, which can synergistically accelerate cell division and proliferation [35, 36]. Attenuated proliferation and promoted apoptosis of GCs accompanying IGF-1R downregulated were detected in our study. The ways introduced above may be involved in the regulation of IGF-1R to biological behaviors of GCs.

The mRNA and protein of IGF-1R are expressed in GCs throughout the entire stage of follicular growth. In patients without ovulation, the expression of IGF-1R in the primordial follicles and the transitional follicles was significantly higher than that of normal women or ovulating patients [37]. We also detected higher IGF-1R in patients with PCOS, which explained the synchronous development of numbers of follicles at the early stages. Another study found that in vitro culture of isolated ovarian cortical, hyperphysiological doses of IGF-1 could promote the transition of primordial follicles to early preantral follicles, and accelerate the growth of preantral follicle, leading to a significantly higher proportion of growing follicles than normal [38]. At the same time, high IGF-1 and GH levels synergistically elevate LH and androgen levels, exacerbating hormone disorder in patients with PCOS [39]. Actually, apart from influence on folliculogenesis, high concentration of free serum IGF-1 in patients with PCOS could adversely affect embryo implantation, causing higher blastocyst absorption rate and pregnancy miscarriages [40, 41]. Therefore, upregulation of miR-99a may be an effective method to attenuate the adverse influences of excessive activation of the IGF-1/IGF-1R system in PCOS.

It was reported that IGF-1 and IGFBP1 were significantly elevated in the endometrium of patients with PCOS, which may involve insulin-related signaling pathways. The present study showed that serum IGFBP 1 significantly decreased in patients with PCOS and was negatively related with insulin level; thus, the decline of IGFBP 1 was considered to correlate with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia [42]. We proposed another possibility that insulin could affect IGF-1/IGF-1R level via regulating miR-99a expression. IGF-1R has a structural similarity with insulin receptor, and cross-binding exists between IGF1/insulin and mutual receptors, although the binding force is much lower. Li et al. found that insulin-induced IGF-1/mTOR pathway activation was accompanied by a significantly reduced miR-99a level, and that elevated IGF-1 enhanced insulin resistance in patients with PCOS. This indicates that insulin resistance, IGF system, and the expression of miR-99a possess some kind of latent mutual effects [21, 43]. Wei Li et al., found that insulin could inhibit the expression of miR-99a and activated mTOR pathways to increase blood sugar consumption and the production of lactic acid. Further upregulation of miR-99a could offset the effect of mTOR activation induced by insulin, indicating a role of miR-99a in the regulation of glucose metabolic balance [44]. Cai et al. [45] found that miR-145 expression gradually decreased while insulin increased from 0 to 80 ng/ml in granulosa cells. Zhang et al. [25] also demonstrated a declining trend of miR-99a in vascular smooth muscle cells and significance showed when insulin concentration exceeded 100 ng/ml. These results were highly in consistence with ours. That means, for patients with PCOS commonly seen with hyperphysiological insulin level beyond 80 ng/ml, miR-99a could be altered and participates in the metabolic regulation and folliculogenesis through the way mentioned before. Furthermore, a more severe insulin resistant state may indicate a lower miR-99a and more disordered endocrine homeostasis.

To sum up, we proved the regulation of miR-99a to biological functions of human GCs via targeting IGF-1R. Meanwhile, insulin could inhibit miR-99a expression, especially at a concentration exceeding 80 ng/ml. Hyperinsulinemia of PCOS may partly explain the decreased miR-99a level in GCs. For another, considering that IGF-1R and its downstream signaling pathways regulate the proliferation and apoptosis of GCs to a great extend, insulin/miR-99a/IGF-1R may be closely correlated with the disorder of follicular development during the course of PCOS. However, some limitations in our study could not be ignored. To begin with, we collected and examined miR-99a in isolated GCS from postovulatory follicles. It has been clarified that the development model of GCs in PCOS is not the same during the whole stage from primordial to antral follicles and finally postovulatory follicles. Secondly, we designed our study based on the human granulosa-like cell line COV434, which was not perfectly representative of the biological behaviors and functions of GCs in patients with PCOS. Last but not least, we did not pitch in a deeper research on the accurate mechanisms of how IGF-1R regulated the functions of GCs. In addition, miR-99a could affect other aspects of PCOS through different pathways. For all these reasons, GCs from early, middle, and late developmental stages should be collected and compared, respectively. The study conclusions should be verified in primary culture of GCs from PCOS and normal people. The change of miR-99a level after treatment for PCOS could also be evaluated to affirm their relationship. In addition, further exploration of miR-99a’functions in PCOS and the definite mechanisms should be proceeded. However, we do find the relationship between miR-99a and PCOS. MiR-99a might act as a marker as well as a therapeutic target of PCOS in the future.

Conclusions

MiR-99a could regulate the proliferation and apoptosis of GCs via targeting IGF-1R. Meanwhile, the decreased miR-99a level and increased IGF-1R level in women with PCOS further indicated a marker of miR-99a for PCOS in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81401268).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Qiaohong Lai, Phone: +86-13995632591, Email: lqh74@126.com.

Lei Jin, Phone: +86-13707105776, Email: leijintj@163.com.

References

- 1.Dalmay T. MicroRNAs and cancer. J Intern Med. 2008;263(4):366–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKenna LB, Schug J, Vourekas A, McKenna JB, Bramswig NC, Friedman JR, et al. MicroRNAs control intestinal epithelial differentiation, architecture, and barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1654–1664. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan C, Lin Y, Mao Y, Huang Z, Liu AY, Ma H, et al. MicroRNA-543 suppresses colorectal cancer growth and metastasis by targeting KRAS, MTA1 and HMGA2. Oncotarget. 2016;7(16):21825–21839. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge X, Liu X, Lin F, Li P, Liu K, Geng R, et al. MicroRNA-421 regulated by HIF-1alpha promotes metastasis, inhibits apoptosis, and induces cisplatin resistance by targeting E-cadherin and caspase-3 in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(17):24466–24482. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shukla GC, Singh J, Barik S. MicroRNAs: processing, maturation, target recognition and regulatory functions. Mol Cell Pharmacol. 2011;3(3):83–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mei LL, Qiu YT, Huang MB, Wang WJ, Bai J, Shi ZZ. MiR-99a suppresses proliferation, migration and invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells through inhibiting the IGF1R signaling pathway. Cancer Biomark. 2017;20:527–537. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Li Y, Qi W, Zhang N, Sun M, Huo Q, et al. MicroRNA-99a inhibits tumor aggressive phenotypes through regulating HOXA1 in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(32):32737–32747. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xing B, Ren C. Tumor-suppressive miR-99a inhibits cell proliferation via targeting of TNFAIP8 in osteosarcoma cells. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(2):1082–1090. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maugeri M, Barbagallo D, Barbagallo C, Banelli B, Di Mauro S, Purrello F, et al. Altered expression of miRNAs and methylation of their promoters are correlated in neuroblastoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(50):83330–83341. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weroha SJ, Haluska P. The insulin-like growth factor system in cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2012;41(2):335–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodarzi MO, Dumesic DA, Chazenbalk G, Azziz R. Polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(4):219–231. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran L, Teede H. Metabolic features of the reproductive phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(4):477–488. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eek D, Paty J, Black P, Celeste Elash CA, Reaney M. A comprehensive disease model of polycystic ovary syndrome (Pcos) Value Health. 2015;18(7):A722. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Piperi C, Spina J, Argyrakopoulou G, Papanastasiou L, Bergiele A, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: the influence of environmental and genetic factors. Hormones. 2006;5(1):17–34. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.11165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Artimani T, Saidijam M, Aflatoonian R, Amiri I, Ashrafi M, Shabab N, Mohammadpour N, Mehdizadeh M. Estrogen and progesterone receptor subtype expression in granulosa cells from women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(5):379–383. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.1001733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stubbs SA, Stark J, Dilworth SM, Franks S, Hardy K. Abnormal preantral folliculogenesis in polycystic ovaries is associated with increased granulosa cell division. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4418–4426. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das M, Djahanbakhch O, Hacihanefioglu B, Saridogan E, Ikram M, Ghali L, Raveendran M, Storey A. Granulosa cell survival and proliferation are altered in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):881–887. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang RJ, Cook-Andersen H. Disordered follicle development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;373(1–2):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu YS, Sui HS, Han ZB, Li W, Luo MJ, Tan JH. Apoptosis in granulosa cells during follicular atresia: relationship with steroids and insulin-like growth factors. Cell Res. 2004;14(4):341–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cakir E, Topaloglu O, Colak Bozkurt N, Karbek Bayraktar B, Gungunes A, Sayki Arslan M, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1, liver enzymes, and insulin resistance in patients with PCOS and hirsutism. Turkish J Med Sci. 2014;44(5):781–786. doi: 10.3906/sag-1303-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hossain MM, Cao M, Wang Q, Kim JY, Schellander K, Tesfaye D, Tsang BK. Altered expression of miRNAs in a dihydrotestosterone-induced rat PCOS model. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth LW, McCallie B, Alvero R, Schoolcraft WB, Minjarez D, Katz-Jaffe MG. Altered microRNA and gene expression in the follicular fluid of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31(3):355–362. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0161-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Zhang X, Shi C, Lin J, Chen G, Wu B, Wu L, Shi H, Yuan Y, Zhou W, Sun Z, Dong X, Wang J. Altered microRNAs expression profiling in cumulus cells from patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Transl Med. 2015;13:238. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0605-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang ZW, Guo RW, Lv JL, Wang XM, Ye JS, Lu NH, Liang X, Yang LX. MicroRNA-99a inhibits insulin-induced proliferation, migration, dedifferentiation, and rapamycin resistance of vascular smooth muscle cells by inhibiting insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and mammalian target of rapamycin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486(2):414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tao J, Yang X, Han Z, Lu P, Wang J, Liu X, Wu B, Wang Z, Huang Z, Lu Q, Tan R, Gu M. Serum MicroRNA-99a helps detect acute rejection in renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(6):1683–1687. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.04.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang SY, Wang YQ, Gao HM, Wang B, He Q. The clinical value of circulating miR-99a in plasma of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(24):5193–5197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin Y, Tymen SD, Chen D, Fang ZJ, Zhao Y, Dragas D, Dai Y, Marucha PT, Zhou X. MicroRNA-99 family targets AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in dermal wound healing. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao G, Yin M, Lian J, Tian H, Liu L, Li X, Sun F. MicroRNA-224 is involved in transforming growth factor-beta-mediated mouse granulosa cell proliferation and granulosa cell function by targeting Smad4. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(3):540–551. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei L, Jin S, Gonzalez G, Behringer RR, Woodruff TK. The regulatory role of Dicer in folliculogenesis in mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;315(1–2):63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong X, Luense LJ, McGinnis LK, Nothnick WB, Christenson LK. Dicer1 is essential for female fertility and normal development of the female reproductive system. Endocrinology. 2008;149(12):6207–12. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding CF, Chen WQ, Zhu YT, Bo YL, Hu HM, Zheng RH. Circulating microRNAs in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Fertil. 2015;18(1):22–29. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.956811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kota J, Chivukula RR, O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Montgomery CL, Hwang HW, Chang TC, Vivekanandan P, Torbenson M, Clark KR, Mendell JR, Mendell JT. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137(6):1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teixeira Filho FL, Baracat EC, Lee TH, Suh CS, Matsui M, Chang RJ, Shimasaki S, Erickson GF. Aberrant expression of growth differentiation factor-9 in oocytes of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(3):1337–1344. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li D, Liu X, Lin L, Hou J, Li N, Wang C, Wang P, Zhang Q, Zhang P, Zhou W, Wang Z, Ding G, Zhuang SM, Zheng L, Tao W, Cao X. MicroRNA-99a inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth and correlates with prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(42):36677–36685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.270561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brahmkhatri VP, Prasanna C, Atreya HS. Insulin-like growth factor system in cancer: novel targeted therapies. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:538019–538024. doi: 10.1155/2015/538019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stubbs SA, Webber LJ, Stark J, Rice S, Margara R, Lavery S, Trew GH, Hardy K, Franks S. Role of insulin-like growth factors in initiation of follicle growth in normal and polycystic human ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(8):3298–3305. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Louhio H, Hovatta O, Sjoberg J, Tuuri T. The effects of insulin, and insulin-like growth factors I and II on human ovarian follicles in long-term culture. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6(8):694–698. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.8.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Premoli AC, Santana LF, Ferriani RA, Moura MD, De Sa MF, Reis RM. Growth hormone secretion and insulin-like growth factor-1 are related to hyperandrogenism in nonobese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(6):1852–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Velazquez MA, Hermann D, Kues WA, Niemann H. Increased apoptosis in bovine blastocysts exposed to high levels of IGF1 is not associated with downregulation of the IGF1 receptor. Reproduction. 2011;141(1):91–103. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo L, Wang Q, Chen M, Yuan G, Wang Z, Zhou C. IGF-1 and IGFBP-1 in peripheral blood and decidua of early miscarriages with euploid embryos: comparison between women with and without PCOS. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(7):538–542. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2016.1138459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Homburg R, Pariente C, Lunenfeld B, Jacobs HS. The role of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and IGF binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) in the pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1992;7(10):1379–1383. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thierry van Dessel HJ, Lee PD, Faessen G, Fauser BC, Giudice LC. Elevated serum levels of free insulin-like growth factor I in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(9):3030–3035. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.9.5941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W, Wang J, Chen QD, Qian X, Li Q, Yin Y, Shi ZM, Wang L, Lin J, Liu LZ, Jiang BH. Insulin promotes glucose consumption via regulation of miR-99a/mTOR/PKM2 pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e64924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai G, Ma X, Chen B, Huang Y, Liu S, Yang H, Zou W. MicroRNA-145 negatively regulates cell proliferation through targeting IRS1 in isolated ovarian granulosa cells from patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Sci. 2016;24(6):902–910. doi: 10.1177/1933719116673197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]