Abstract

Policy Points.

Current efforts to reduce infant mortality and improve infant health in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) can benefit from awareness of the history of successful early 20th‐century initiatives to reduce infant mortality in high‐income countries, which occurred before widespread use of vaccination and medical technologies.

Improvements in sanitation, civil registration, milk purification, and institutional structures to monitor and reduce infant mortality played a crucial role in the decline in infant mortality seen in the United States in the early 1900s.

The commitment to sanitation and civil registration has not been fulfilled in many LMICs. Structural investments in sanitation and water purification as well as in civil registration systems should be central, not peripheral, to the goal of infant mortality reduction in LMICs.

Context

Between 1915 and 1950, the infant mortality rate (IMR) in the United States declined from 100 to fewer than 30 deaths per 1,000 live births, prior to the widespread use of medical technologies and vaccination. In 2015 the IMR in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) was 53.2 deaths per 1,000 live births, which is comparable to the United States in 1935 when IMR was 55.7 deaths per 1,000 live births. We contrast the role of public health institutions and interventions for IMR reduction in past versus present efforts to reduce infant mortality in LMICs to critically examine the current evidence base for reducing infant mortality and to propose ways in which lessons from history can inform efforts to address the current burden of infant mortality.

Methods

We searched the peer‐reviewed and gray literature on the causes and explanations behind the decline in infant mortality in the United States between 1850 and 1950 and in LMICs after 2000. We included historical analyses, empirical research, policy documents, and global strategies. For each key source, we assessed the factors considered by their authors to be salient in reducing infant mortality.

Findings

Public health programs that played a central role in the decline in infant mortality in the United States in the early 1900s emphasized large structural interventions like filtering and chlorinating water supplies, building sanitation systems, developing the birth and death registration area, pasteurizing milk, and also educating mothers on infant care and hygiene. The creation of new institutions and policies for infant health additionally provided technical expertise, mobilized resources, and engaged women's groups and public health professionals. In contrast, contemporary literature and global policy documents on reducing infant mortality in LMICs have primarily focused on interventions at the individual, household, and health facility level, and on the widespread adoption of cheap, ostensibly accessible, and simple technologies, often at the cost of leaving the structural conditions that determine child survival largely untouched.

Conclusions

Current discourses on infant mortality are not informed by lessons from history. Although structural interventions were central to the decline in infant mortality in the United States, current interventions in LMICs that receive the most global endorsement do not address these structural determinants of infant mortality. Using a historical lens to examine the continued problem of infant mortality in LMICs suggests that structural interventions, especially regarding sanitation and civil registration, should again become core to a public health approach to addressing infant mortality.

Keywords: infant mortality, history, sanitation, low‐ and middle‐income countries, civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS)

The infant mortality rate (imr) has long been a measure of whether a society's social, political, and economic structures and health systems enable children to complete their first year of life.1, 2 In the United States, the IMR declined from 100 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1915 to fewer than 10 deaths per 1,000 live births by 1990, with the sharpest decline occurring between 1915 and 1950, before widespread use of medical technologies and vaccines.2 Although other high‐income countries made similar progress in the early 20th century, such a sharp decline did not take place in many low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) until after the end of the Second World War and is yet to take place in some countries.3 For example, in 2015, the IMR in LMICs was 53.2 deaths per 1,000 live births (comparable to the United States in 1935, when the IMR was 55.7 deaths per 1,000 live births), and globally ranged from a maximum of 96 deaths per 1,000 live births in Angola to a minimum of 1.5 deaths per 1,000 live births in Luxembourg.4

Partly in response to persistent inequities in the IMR across and within countries, ie, differences in rates across groups that are unnecessary, unjust, and in principle preventable,5, 6, 7, 8, 9 there has been a marked increase in global commitments to child and neonatal survival, through a growing number of partnerships and policies,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 combined with an increase in official development assistance (ODA), government aid that promotes and targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries. For example, 1 study found that the total aid disbursed to 4 sectors (health, education, water and sanitation, and food and humanitarian assistance) for child survival in 134 countries more than doubled between 2000 and 2014, rising from $22.62 billion to $59.29 billion. This increase in aid was noted in all income groups and regions, with sub‐Saharan Africa receiving the largest amount in disbursements.17

In this context, the new Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 for 2030 seeks to “end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births, and under‐5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births.”18 Notably, this SDG has been articulated following the global failure to achieve Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4, set in 2000, which had aimed to reduce the mortality rate among children under 5 by two‐thirds between 1990 and 2015. Although the child mortality rate dropped by more than half, from 90 to 43 deaths per 1,000 live births, and the global IMR declined from 62.8 to 31.7 deaths per 1,000 births between 1990 and 2015,4 MDG 4 was not achieved. Worryingly, in 2015 the UN Inter‐agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation concluded that to meet the new SDG 3 target, 63 countries would need marked acceleration of their current rates of reduction.19

Critical work accordingly is needed to understand and address reasons for the gap between recent and projected goals to reduce the IMR in LMICs—and we believe useful guidance can be gleaned from a deeper look into the early 20th‐century history of the reduction of IMR in high‐income countries. Specifically, we examine the historical evidence base of the IMR decline in the United States in the early 1900s and the role of public health institutions and structural interventions in enabling this decline. We then use the key themes that emerge from this historical analysis to assess current efforts in LMICs, which emphasize individual‐level biomedical interventions for infant mortality. As the historical record clarifies, current approaches are not inevitabilities: in the early 1900s, policymakers, public health experts, and practitioners made—and funded—a set of different choices that effectively lowered infant mortality.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27

The literature contains compelling arguments for why history should inform global public health discourses,5, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 and our historically informed analysis not surprisingly engages with long‐standing tensions between structural and individualist approaches to improving population health and reducing health inequities.5, 6, 8 In offering such an analysis, we do not assume a contextual, political, or economic equivalency between the turn of the 20th century in the United States and the turn of the 21st century globally. Rather, as Randall Packard observed in his 2016 book A History of Global Health, “we need to understand these forces and how they have defined and limited global health interventions. We also need to acknowledge the limitations and consequences of the choices that have been made.”6 In this vein, this paper seeks to contribute to the paucity of literature connecting historical and current efforts to reduce infant mortality in order to critique and inform current policies and interventions to improve child survival and reduce health inequities.

Methods

To understand the key milestones in policy, governance, law, and public health that contributed to reducing infant mortality, we searched for literature on the causes and explanations behind the decline in infant mortality in the United States between 1850 and 1950. Keywords used included “United States,” “infant mortality,” “1850‐1950,” “causes,” “determinants,” and specific search terms for key themes in the literature (eg, “sanitation,” “medicine,” “water,” “registration,” “hygiene,” “breastfeeding,” “education”). We included secondary literature from history, economics, social sciences, and public health that examined the decline in infant mortality. Our goal was not to review primary sources or to disentangle the precise and relative effects of the range of causal factors that decreased infant mortality, especially given that data on IMR were initially absent and only began to be compiled during the time period of interest.34 Given fragmentary, limited, and not easily comparable federal, state, and local funding data, we did not attempt to examine the financial commitments from public and private organizations to address infant mortality during this time period. Rather, our intent is to summarize arguments for the decline, as offered both by historical contemporaries and by contemporary historians, and examine whether structural interventions were central or peripheral to the reduction of infant mortality.

We conducted a similar search of peer‐reviewed and gray literature to examine contemporary research on the causes and determinants of infant and neonatal mortality in LMICs, as well as efforts made by donors, the United Nations, and other global health institutions to address infant mortality between 2000 and 2015. Although this time period does not represent the totality of activities in LMICs, it reflects global efforts made in the 21st century, the MDG and SDG periods, activities supported by the large increase in ODA synonymous with this period,17, 35 and the increase in global attention toward child survival.13, 14 We used keywords for infant mortality combined with search terms for low‐ and middle‐income countries (eg, “developing,” “resource poor,” “LMIC”) and we conducted our searches by using PubMed, Google Scholar, and the institutional websites of the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and other institutions with a mandate to address infant mortality.

To capture the conceptual frameworks and recommendations employed regarding IMR reduction, our search additionally encompassed global targets, policy documents, resolutions of the United Nations, strategies, toolkits, operational frameworks, technologies, and interventions to address infant mortality, including infant pneumonia, diarrhea, and nonimmunization. We deliberately focused on the explicitly stated goals and aims of policies to reduce IMR that have been developed by donors, Western aid agencies, and other global organizations so as to understand what these global health institutions value and fund. It was therefore outside the scope of our review to evaluate the implementation of programs or address policies and initiatives (a) not expressly designed to reduce IMR (eg, sanitation projects with no explicit IMR reduction target) and (b) independently implemented by specific LMIC governments (ie, not explicitly tied to global initiatives). This focus enabled us to examine common and divergent themes between two moments in work to reduce IMR: public health policy in the United States at the turn of the 20th century and global health policy at the turn of the 21st century.

Infant Mortality Trends in the United States and Low‐ and Middle‐Income Countries

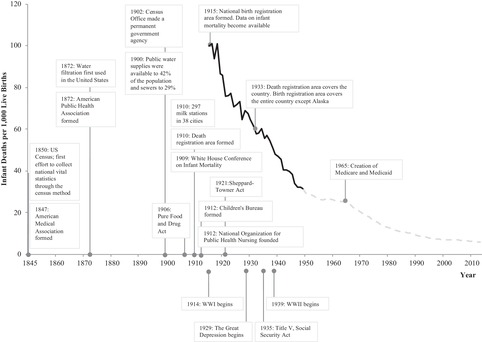

Although the current definition of the IMR—the number of deaths before 1 year of age per 1,000 live births—was not commonly accepted until the 1880s, estimates suggest that in 1860, infant mortality was 197 deaths per 1,000 live births for the whole American population and 350 deaths per 1,000 live births for enslaved populations.36 Efforts to gather national data on birth and death rates included the white and black population, albeit at an unequal pace: in 1900 the death registration area included 26% of the total population, but only 4.4% of the black population.37 In 1916, as national data became available, the mortality rate was 101 deaths per 1,000 live births (white: 99.0/1,000; black: 184.3/1,000).38 By 1940, infant mortality had decreased to 47 deaths per 1,000 live births (white: 43.2/1,000; black: 72.9/1,000),38 and by 1950, the IMR was 29.2 per 1,000 live births. Figure 1 charts this decline along with the coinciding development of public health policies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including the efforts to improve sanitation, expand birth registration, and create institutions to address infant health, all of which played a role in addressing the leading causes of infant and child mortality and decreasing the burden of infectious disease. In the late 1800s, infants most often died from diarrheal diseases, diphtheria, measles, pneumonia and influenza, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, typhoid and paratyphoid fevers, and whooping cough.39 However, by 1920 these deaths had greatly diminished, and between 1900 and 1998, the percentage of child deaths attributable to infectious diseases declined from 61.6% to 2%.21, 39 In addition, there was a dramatic reduction in water‐ and food‐borne diseases (typhoid, cholera, dysentery, and nonrespiratory tuberculosis), from an overall mortality rate of 214 per 100,000 in 1848‐1854 to virtual elimination by 1970.22

Figure 1.

The Infant Mortality Rate in the United States (1915‐2013) and Key Milestones

The infant mortality rate is the number of deaths among infants under 1 year, excluding fetal deaths; rates per 1,000 registered live births.

Data for events and milestones derived from Abbott 1923,46 Brosco 1999,47 Guyer et al. 2000,39 Cutler and Miller 2005,48 Haines 2000,36 Hetzel 1950,49 Nathanson 2007,50 Pearl 1921,51 Porter 1999,40 Preston 1996,41 Shapiro 1950,42 Woodbury 1936,43 Stern and Markel 2002,27 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1999,26 Fee 1994,44 Lindenmeyer 1995.45

Data for infant mortality rate derived from the US Census Bureau (1900‐1970)52 and the National Center for Health Statistics (2000‐2011 and 2013).53 , 54

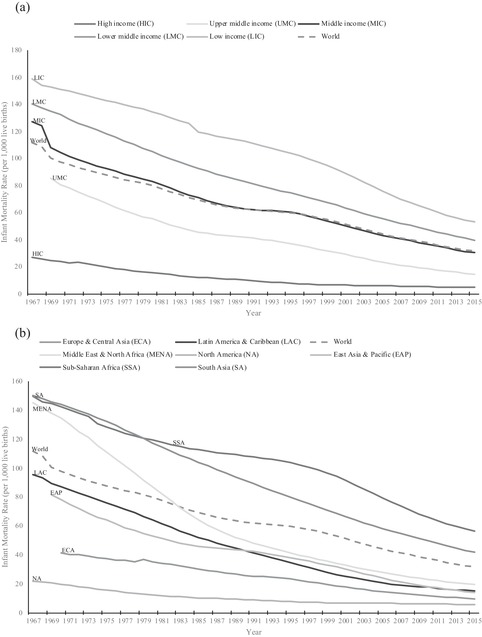

To contextualize the early 20th‐century decline in infant mortality in the United States, Figure 2 shows the average IMR in World Bank income groups (2a) and regions (2b) between 1967 and 2015.4 By 1967, when World Bank IMR data became available, high‐income countries, North America, and Europe had completed their largest declines. Between 1967 and 2015, infant mortality declined by 22.6 deaths per 1,000 live births among high‐income countries and by more than 100 deaths per 1,000 live births in LMICs. During the same period, the IMR declined by 16.4 deaths per 1,000 live births in North America and by 31.7 deaths per 1,000 live births in Europe and Central Asia. In contrast, the IMR declined by 125.5 deaths in the Middle East and North Africa, followed by 108.4 deaths per 1,000 live births in South Asia.

Figure 2.

Infant Mortality Rates for Countries, Stratified by Income Group (a) and Region (b), 1967‐2015

Data derived from the World Bank 2015.4

In 2015 the IMR in LMICs was 53.2 deaths per 1,000 live births, which is comparable to the United States in 1935 when the IMR was 55.7 deaths per 1,000 live births. The IMR ranged from a maximum of 96 deaths per 1,000 live births in Angola to a minimum of 1.5 deaths per 1,000 live births in Luxembourg.4

Factors Contributing to the Decline in Infant Mortality in the United States in the Early 1900s

In the early 1900s, high infant mortality became one of the targets of social reform movements in the United States, galvanizing public health and policy interventions at the state and national level that focused on reducing poverty and improving conditions of the poor. Table 1 outlines the literature we identified to understand the decline in infant mortality and the factors mentioned by each author as contributing to this decline. There was consensus among public health professionals in that era, shared by contemporary scholars, that public health programs like filtering and chlorinating water supplies, building sanitation systems, expanding the birth registration area, pasteurizing milk, and subsequent efforts to educate mothers on infant care and hygiene played a central role in the decline in infant mortality (Appendix).20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Table 1.

Overview of the Literature on the Factors That Contributed to Reduced Infant Mortality in the United States in the Early 20th Century: (A) Governance and New Institutionsa; (B) Sanitationb; (C) Health Education for Mothersc; (D) Civil and Vital Registrationd; (E) Breastfeeding and Milk Purificatione; (F) Medical Caref

| Source | Contributing Factors Cited | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Author(s) | Title | A | B | C | D | E | F |

| 1923 | Abbott 46 | Ten Years’ Work for Children | x | x | x | x | ||

| 1926 | Woodbury 55 | Infant Mortality and Its Causes: With an Appendix on the Trend of Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 1933 | Tisdale 70 | The Work of the State Sanitary Engineer | x | x | x | |||

| 1950 | Hetzel 49 | U.S. Vital Statistics System | x | |||||

| 1950 | Shapiro 42 | Development of Birth Registration and Birth Statistics in the United States | x | x | ||||

| 1978 | Condran, Crimmins‐Gardner 23 | Public Health Measures and Mortality in U.S. Cities in the Late Nineteenth Century | x | |||||

| 1985 | Gaspari, Woolf 24 | Income, Public Works, and Mortality in Early Twentieth‐Century American Cities | x | |||||

| 1988 | Combs‐Orme 71 | Infant Mortality and Social Work: Legacy of Success | x | x | x | |||

| 1990 | Meckel 72 | Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850–1929 | x | x | x | |||

| 1990 | Ewbank, Preston 56 | Personal Health Behavior and the Decline in Infant and Child Mortality: The United States, 1900–1930 | x | x | x | |||

| 1991 | Preston, Haines 21 | Fatal Years: Child Mortality in Late Nineteenth‐Century America | x | x | x | x | ||

| 1994 | Fee 44 | Public Health and the State: The United States | x | x | x | |||

| 1994 | Condran, Preston 57 | Child Mortality Difference, Personal Health Care Practices, and Medical Technology: The United States, 1900–1930 | x | x | x | |||

| 1995 | Lindenmeyer 45 | The U.S. Children's Bureau and Infant Mortality in the Progressive Era | x | x | x | |||

| 1996 | Preston 41 | American Longevity: Past, Present, and Future | x | x | x | |||

| 1999 | Brosco 47 | The Early History of the Infant Mortality Rate in America: “A Reflection Upon the Past and a Prophecy of the Future” | x | x | ||||

| 1999 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 26 | Achievements in Public Health, 1900–1999: Healthier Mothers and Babies | x | x | x | |||

| 2000 | Almgren, Kemp, Alison 34 | The Legacy of Hull House and the Children's Bureau in the American Mortality Transition | x | x | ||||

| 2001 | Fishback, Haines, Kantor 38 | The Impact of the New Deal on Black and White Infant Mortality in the South | x | x | ||||

| 2002 | Stern, Markel 27 | Formative Years: Children's Health in the United States, 1880–2000 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 2003 | Wolf 73 | Low Breastfeeding Rates and Public Health in the United States | x | x | ||||

| 2004 | Markel, Golden 31 | Children's Public Health Policy in the United States: How the Past Can Inform the Future | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 2004 | Condran, Lentzner 20 | Early Death: Mortality Among Young Children in New York, Chicago, and New Orleans | x | x | x | |||

| 2005 | Cutler, Miller 48 | The Role of Public Health Improvements in Health Advances: The Twentieth‐Century United States | x | |||||

| 2007 | Nathanson 50 | Disease Prevention as Social Change: The State, Society, and Public Health in the United States, France, Great Britain, and Canada | x | x | x | |||

| 2007 | Lee 74 | Infant Mortality Decline in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries: The Role of Market Milk | x | |||||

| 2008 | Miller 78 | Women's Suffrage, Political Responsiveness, and Child Survival in American History | x | x | x | |||

| 2012 | Thompson, Keeling 82 | Nurses' Role in the Prevention of Infant Mortality in 1884–1925: Health Disparities Then and Now | x | |||||

| 2013 | Stoll 25 | American Pediatric Society 2013 Presidential Address: 125th Anniversary of the American Pediatric Society— Lessons From the Past to Guide the Future | x | x | ||||

| 2014 | Moehling,Thomasson 83 | Saving Babies: The Impact of Public Education Programs on Infant Mortality | x | x | ||||

| 2015 | Alsan, Goldin 76 | Watersheds in Infant Mortality: The Role of Effective Water and Sewerage Infrastructure, 1880 to 1915 | x | |||||

| Total | 16 | 15 | 19 | 6 | 19 | 6 | ||

Governance and new institutions includes the role of the Children's Bureau, state and national health boards, policy changes, new laws and regulations, and the role of sanitary engineers.

Sanitation includes water purification, sewers, and sewage treatment.

Health education for mothers includes the delivery of information (eg, on breastfeeding, registration, infant care, home hygiene) via pamphlets, newspapers, home visits, clinics, and/or by social workers, volunteers, advocates, and nurses.

Civil and vital registration includes creating the birth and death registration areas, promoting registration, and the laws to enable registration.

Breastfeeding and milk purification includes decontaminating milk, encouraging mothers to breastfeed, establishing milk stations, and passing pasteurization laws.

Medical care includes the role of dispensaries, pediatricians, and vaccinations.

In reports to the Census Bureau in 1900, local health authorities clearly considered structural public health measures to be the major reason for IMR declines.23 Writing in 1926, Woodbury attributed the decrease of the infant mortality rate by one‐fifth between 1915 and 1921 to increased public interest in infant health, which galvanized infant welfare work, the establishment of child hygiene divisions in 36 states, the improvement of standards for milk distribution, and the training of physicians.55 More contemporary accounts of infant mortality decline in the early 1900s tell a similar story. In 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention described sanitation, water purification, the Children's Bureau, and milk purification as the major public health achievements behind the decline in infant mortality in the early 1900s.26 In a 2004 historical analysis of the primary literature, Condran and Lentzner described how 20th‐century debates on the mortality transition variously argued the determinants were (1) inevitable effects of economic variables on the health of populations, such that mortality declines were viewed as a largely unanticipated consequence of structural change vs (2) deliberate policy‐directed efforts of individuals, governments, and the medical community to lower mortality levels.20 Rejecting this dichotomy, Condran and Lentzner concluded that the evidence suggests that no single factor can explain the improvements in infant health by the last quarter of the 19th century.20 In 1990, Ewbank and Preston suggested that changes in health practices in homes related to infant feeding and hygiene were an important contributing factor,56 and in 1994, Condran and Preston also emphasized the importance of maternal behavior change.57 Although the emphasis on salient factors did vary across the sources we reviewed, the literature cited in Table 1 indicates that public health professionals and other scholars, past and present, have primarily argued that the marked decline in infant mortality was due more to social and environmental changes than to advances in clinical practices and medicine.41, 42, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76

Arguing against overemphasizing the contribution of the medical establishment, the historians Gaspari and Woolf in 1985 observed that “while sanitary engineers were making some headway in decreasing mortality rates, physicians seemed to be having the opposite impact,” in part due to the poor quality of medical training and care in the early 1900s.24 As they and other historians have recounted, the decline in IMR began prior to the use of drugs or childhood vaccines and before the development of pediatric surgery or intensive care technologies.44, 50, 57, 72 Notably, in the early 1900s, few births occurred in hospitals,30 and no medical treatments could cure either diarrheal disease or pneumonia, which were the 2 leading causes of infant death in the early decades of the 20th century.34 The diphtheria antitoxin was the only effective chemotherapy, and physicians instead chiefly relied on drugs they had used since the 19th century, including digitalis, quinine, and opium derivatives.77 It was not until the 1940s that the widespread use of antibiotics, fluid and electrolyte therapy, and safe blood transfusion became possible—and these clinical remedies were only available to infants who could access hospitals.25, 26, 30 Although physicians took a far more prominent and active role in the children's health movement after 1880,27 the American Academy of Pediatrics was not formed until 1930, much later than other institutional efforts to improve child health like the 1912 Children's Bureau. The net implication is that US initiatives in the early 20th century designed to address infant mortality relied chiefly on public health, not biomedical interventions, and notably reduced the IMR.50

Further motivating these social interventions was a growing awareness of socioeconomic and racial/ethnic inequalities in infant mortality. In 1926, Woodbury drew on studies of infant mortality in 8 cities carried out by the US Children's Bureau among 22,422 live born infants between 1911 and 1915 to show that the IMR among “colored” infants (154.4 deaths per 1,000 live births) was nearly 1.5 times that of white infants (111.2), and the IMR among infants of foreign‐born mothers (127.0) was higher than among infants of native white mothers (93.8).55 Contemporary analyses, based on more comprehensive data, also provide evidence of socioeconomic gradients in infant mortality during the early 20th century: as reported by Preston and Haines in 1991, literate mothers had better child survival than illiterate ones, and higher infant mortality rates among working mothers were concentrated among black and foreign‐born mothers.21 Their analyses also indicate that a contributing factor to the early 20th‐century racial/ethnic inequities in the IMR was that the bulk of the US black population resided in rural areas, which did not benefit from the urban gains in infant mortality reduction that had been brought about by urban initiatives to improve water supplies, sewage, and food and milk quality.2 Reflecting these geographic disparities, in 1933 the infant mortality rate among black infants was almost 2 times that of white infants (91.3 compared to 52.8 deaths per 1,000 live births).43

The context within which this public health response occurred is of note. Between 1865 and 1920, considerable industrial output was devoted to providing infrastructure and materials to house, transport, and deliver public services for the shift toward cities36 combined with improvements in national transportation, agricultural technology, living conditions, electricity, and refrigeration.25 Germ theory emerged as a way to understand disease, which marked a shift away from theories of contagion and miasma.5, 29, 34, 40 The Progressive moment toward the turn of the century stressed the need to systematize and expand public health beyond the level of individual cities and advocated for universal standards of public hygiene administered by a system of public health organization.5, 40, 50 The efforts of suffragettes in the women's suffrage movement between 1869 and 1920 led to women gaining the right to vote in 1920, and throughout that period, women's groups played a central role in social activism and public health efforts, including the formation and implementation of the Children's Bureau and increases in local public health spending.78, 79

These efforts, however, intersected with US racial politics of white supremacy. During the 1880s and 1890s, the system of legal racial discrimination (“Jim Crow”), upheld by government force and extrajudicial violence and terror by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), was established in the US South. This development was part of the white backlash to post–Civil War economic and civil rights gains of the freed, previously enslaved black population.80 The 1920s marked the “second coming of the KKK” throughout the United States.81 Related to this, central to the Progressive movement and interventions into poor, foreign‐born, or black neighborhoods was an ethnocentrism that held white middle‐class values as the ideal.27 As the researchers recount, these tensions were evident in all 3 waves of infant mortality campaigns—environmental sanitation, milk purification, and maternal education—which together led to large reductions, albeit unevenly by race and ethnicity, in infant mortality by 1950.27

With this history in mind, we now turn to analysis of the key factors listed in Table 1 that contributed to the decline in infant mortality in the United States. Our intent is both to examine the development of institutions, policies, and interventions and to set the basis for critiquing the assumptions and approaches to contemporary efforts in LMICs to reduce the IMR.

Governance and New Institutions for Infant and Child Health

The creation of new institutions and policies to advocate for infant health provided technical expertise, mobilized resources, and engaged women's groups, sanitarians, and public health professionals to improve infant health. In the mid‐ to late 1800s, boards of health were established in cities: the first board was established in Louisiana in 1855 and served as a quarantine authority; the first effective state board was established in Massachusetts in 1869.40, 84, 85 Their mandate was to conduct inspections of sanitary conditions, public drainage, food, milk, and quarantine.40, 84 By 1900, the need for coordination across cities led to the establishment of more state boards of health,40 and by 1906, a group of Progressive intellectuals within the American Association for the Advancement of Science began a campaign to establish a federal health department. By 1912 the federal government had made a substantial commitment to public health by turning the Marine Hospital Service into the United States Public Health Service and authorizing it to investigate the causes and spread of diseases; study the problems of sewage, sanitation, and water pollution; and publish health information for the general public.44

There were concurrent efforts to create institutions focused on infant and child health. In 1909 the White House Conferences were initiated and brought experts and activists together to address the needs of children.31 That same year, the American Association for Study and Prevention of Infant Mortality was created to bring the IMR to national attention.47 Several years later, President Roosevelt and President Taft respectively recommended the establishment of the Children's Bureau to Congress. In 1912, the Children's Bureau was created with an appropriation of $25,640. Julia Lathrop, its leader, was the first woman to head a federal agency, and the bureau was the first public agency in the world with a mission to consider the problems of childhood in an integrated way, choosing infant mortality as its first, and central, issue.45, 46, 86 Almgren and others, in 2000, described this as a strategic, popular, and noncontroversial choice, as well as a compelling issue for the thousands of women who had supported the development of the bureau.34, 45, 79 As noted by several of the sources cited in Table 1, the Children's Bureau made several crucial contributions to infant mortality reduction.

First, Lathrop premised the bureau's efforts on the argument that poverty rather than ignorance was the cause of infant mortality, and she chose to address the social conditions that affected infant mortality.45, 87, 88 Second, the bureau strengthened state and national institutions: state child hygiene or child welfare agencies were established in 1912, and by 1920 there were 34 in operation. Although they were typically divisions of state departments of public health, their organization and scope of activities were based on the Children's Bureau's Minimum Standards for Public Protection of the Health of Mothers and Children.34

Third, the bureau conducted research: 10 community studies of infant mortality commissioned between 1913 and 1923 described the social gradient in infant mortality, highlighted efforts to reduce infant mortality, and assessed the care available to women and children.46, 79 Conferences were scheduled in 8 cities to disseminate findings.71 To benefit from lessons from other countries in reducing the IMR, Lathrop and others examined programs and policies in New Zealand,46, 55 which at the time had the lowest national rates of child deaths (but not taking into account the much higher rates of IMR among the indigenous Māori vs New Zealand residents of European ancestry),89 and used Great Britain as an example to argue for greater national and state cooperation to reduce maternal and child deaths.46

Fourth, the bureau ran campaigns and developed programs. Notable examples include a 20‐year‐long national birth registration campaign; maternal education activities between 1912 and 1922 on prenatal, infant, and child care; engagement of women's groups to advocate for improvements in health, welfare, and rights for women and children;34, 46 and the opening of milk centers for working mothers who relied on cow's milk for infants, which were staffed by nurses who discussed infant care and feeding.71 However, as Lindenmeyer wrote in 1995, by 1920 the bureau began to focus less on poverty as a cause of infant death and more on motherhood education, individual family responsibility, and physician‐directed medical care.45

One of the bureau's most significant contributions was the Sheppard‐Towner Act: the bill was introduced in 1918, passed in November 1921 (one year after women's suffrage), and implemented a year later.34, 78, 83 The law appropriated $7 million in federal money for states to promote maternal and infant health and welfare. Funds were used to establish and implement public health clinics, classes for midwives, infant‐care classes, and prenatal care and to pay public health nurses to visit new and expectant mothers.83 By 1930 the legislation had led to the expansion of the birth and death registration area, the establishment of state child hygiene bureaus and divisions, the development of permanent state health centers for mothers and children, and an increase in state appropriations for infant and maternal health.38 Even though the Sheppard‐Towner legislation was repealed in 1929, public health infrastructure supported by this legislation was already in place by the late 1920s. Those advancements included the purification of water, improvements in the disposal of sewage, health education, milk pasteurization, visiting nurses, and maternal education.34, 38, 83

Civil Registration

Between 1850 and 1950, the vital statistics system transformed the measurement of births and deaths and the calculation of mortality rates by providing timely information on births and deaths. The system made the problem of infant deaths visible, including differences between black and white children and between urban and rural children. Although the United States lagged far behind the United Kingdom and several other countries in the quality of its national vital registration data,21, 40, 44, 49, 55, 84 vital statistics emerged in the early to mid‐19th century as a local, then state function and grew in response to local and state needs, allowing it the support it might have lacked if the system had been primarily national.49

Within the United States, the 1850 census marked the first effort to collect national vital statistics on deaths and births. Although emphasis was placed on obtaining mortality statistics, tabulations were also prepared showing the number of enumerated children who were under one year of age as of the census date, in order to compute infant mortality rates.42 National efforts to improve civil registration of births began to gain momentum; the newly formed American Medical Association (AMA) advocated for improving registration and implementing registration laws, which led to six states enacting such laws by 1851. Several years later, the AMA “RESOLVED, That a committee of one from each State be appointed to report upon a uniform system of registration of marriages, births, and deaths.”49 In 1880, the US census, which then was in charge of vital statistics, established a death registration area to measure deaths. Initially the death registration area comprised two states and several cities but had expanded to include the entire country by 1933.49, 88

The 1900 census sample filled many gaps in American demographic history and converted the United States from the industrialized country with the poorest mortality data at the turn of the century to the country with perhaps the richest and most detailed data on infants and children.42 In 1902, the US Bureau of the Census also became a permanent agency of the federal government, authorized to obtain, annually, copies of death records filed in the vital statistics offices of those states and cities having adequate death registration systems and to publish data from these records.39, 49 The presence of a permanent agency to lead the collection of vital statistics was a crucial turning point in efforts to measure infant mortality.

By 1903, when Congress adopted a resolution on the importance of a complete and uniform system of registration throughout the country, several key institutions supported these efforts. The Census Bureau, the AMA, the American Public Health Association (APHA), and other organizations drafted a model law that states could use to improve registration. In 1907 the APHA established a Vital Statistics Section to aid the adoption of uniform registration methods and publication of statistical data.49 In 1915, the US Census and the Children's Bureau worked together to create the US birth registration area, which initially encompassed 31.1% of the population and 10 states and included more than 70% of the population by the early 1920s.46 By 1933 all states were registering live births and deaths with acceptable coverage and providing the required data to the Census Bureau for the production of national birth and death statistics.39 As birth record data became more available, the birth certificate began to increase in value and, in some places, became the primary document for verifying age in entering school and in obtaining work permits.42 When federal and state governments began to enact welfare legislation in the 1920s and 1930s, a birth certificate was used as the legal document to prove the age of recipients.49 After 1946, responsibility for vital statistics shifted from the US Census to the Public Health Service,88 and as health departments employed officers with public health training, records were used for statistical analysis.49

In a 1950 analysis of the development of US vital statistics, Hetzel quoted the following excerpt from a report of the National Resources Committee to describe the process of improving registration:

The long, hard, often discouraging campaign which was fought to bring States, one by one, into the fold constitutes one of the proudest chapters in the history of the Bureau of the Census.… In some States, the boards of health had to be educated to the need, before the citizens of that State could approach the legislature. In others, the legislatures were apathetic, in spite of strong pressures.… Each State had to educate its physicians and undertakers as to their duties, as well as an army of local registrars.49 (p.53)

As this quote attests, those involved in the work of vital registration had the “long view” clearly in mind and saw that these data were truly vital, not only to track mortality, including infant mortality, but also to understand the health and well‐being of the nation.39

Sanitation

From 1850 to 1880, infant mortality was viewed as an urban problem that could be best combated through purifying the water supply and building sewage systems.27 As Duffy wrote, the “sanitary revolution” was in full swing during the last 2 decades of the 19th century.85 By 1890 sewage systems were fairly widespread—of the 96 cities with a population of 10,000 and greater, 73% had sewers, leaving only 26 with no sewers at all—and by 1907, nearly every city in the United States had sewers.90 By 1910, public water supplies were available to 42% of the population and sewers to 29%.36 During this time, the role of sanitary engineer was created in every state health department. In 1933 Ellis S. Tisdale, the director of the Division of Sanitary Engineering in the Charleston, West Virginia, State Department of Health, described how inoculation was a stopgap, and instead emphasized the importance of statewide sanitation control. Sanitary engineers had “a close and vital connection with every water works engineer” and played a role drafting new laws to meet the growing sanitation demands of the state. They functioned as the state technical advisor on questions pertaining to water, milk, sanitation, sewage, malaria, industrial hygiene, and waste disposal.70 Tisdale warned against reducing resources toward sanitation: “Carefully consider the conservation of human life and your natural resources before you apply the pruning knife to this branch of state government.”70

In a 2005 study of clean water technologies in large American cities in the early 20th century, Cutler and Miller suggested these were “likely the most important public health intervention of the 20th Century.”48 They estimated that the introduction of water filtration and chlorination systems could explain nearly half the overall reduction in mortality between 1900 and 1936, three‐quarters of the decline in infant mortality, nearly two‐thirds of the decline in child mortality, and the near eradication of typhoid fever.48 They emphasized that although water systems were expensive, their benefits appear to have been substantially greater than the costs. A 1978 analysis by Condran and colleagues likewise suggested that the provision of central water supplies and sewage systems were central to the “public health movement” in the late 1800s.23 Using data from 1880 to 1915 in Massachusetts, Alsan and Goldin in 2015 showed that appropriate sewage systems and safe, potable water for homes caused a sharp and persistent decrease in infant mortality.76 It is important to note that there are debates about the relative importance of clean water and sewage systems. Some scholars have suggested that filtration of water supplies had a much more clear‐cut effect on mortality reduction,23 while others have argued that removing waste through covered sewers best served the health of urban popluations.24 Others have pointed to the role of campaigns that focused on unclean milk (a source of typhoid; discussed in the next section), which was largely outside the purview of structural efforts to improve sanitation,24 and also to the role of women's suffrage in increasing public spending for health and sanitation through hygiene campaigns.78

Breastfeeding and Milk Purification

In contrast to recognition of the dangers of unclean water in the mid‐19th century, milk began to attract the attention of public health officials in the mid‐1870s, when reformers began to focus on the quality of urban milk supplies.72 Several public health campaigns were initiated. At first, the focus was on improving the compositional integrity of milk and preventing adulteration, dilution, and spoilage. Later, in the 1890s, informed by germ theory and the new science of bacteriology, public health efforts were also directed toward preventing the microbial contamination of milk and cleaning milk supplies.56, 57, 72 This included pasteurizing milk, sealing milk in bottles, and transporting it in refrigerated railroad cars.73

In the last quarter of the 19th century, as working‐class women increasingly entered the industrialized workforce, and with many working while still also caring for infants, breastfeeding declined. Working mothers in particular began to supplement their own milk with cow's milk and wean babies before they were 3 months of age.73 This development meant the unpasteurized market milk supplies contaminated with tuberculosis, typhoid, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and streptococcal germs had a direct effect on infant health.56 Scientists documented, at the beginning of the 20th century, that bacterial counts in the market milk supply in 6 US cities were similar to counts in sewage at that time.74

Public health interventions varied in scope and level. First, dairies and milk suppliers were inspected91 and milk stations were created to provide free or subsidized milk to poor mothers. The first stations were opened in 1893 in New York City. Funded by philanthropist Nathan Straus, these milk depots were the first building blocks of an at least partially state‐supported administrative and clinical infrastructure devoted to infant health.50, 85, 91 By 1910 there were 297 stations in 38 cities, funded by a wide range of charitable agencies, including settlement houses, women's clubs, and children's aid societies.50

Second, pasteurization came to the forefront.20, 57, 74 Milk reformers conceded that milk stations supplied a very small population and structural change was needed to remove poor‐quality milk from the urban milk supply.74 In 1912 the New York City Health Department mandated the pasteurization of all milk coming into the city, well in advance of similar measures in the rest of the world.50 Following this, legislation in the 1920s made the pasteurization of milk mandatory nationwide, which led to the most dramatic changes in the milk supply.20 In a 2007 analysis, Lee reported that the decline in infant mortality was inversely correlated with the cleaning of the market milk supply between 1840 and 1940, a period that also exhibited a decline in breastfeeding and no medical treatment for infantile diarrhea, lending support to the thesis that pasteurization contributed to the IMR decline.74

Third, and last, local public health officials designed interventions to urge mothers to breastfeed for as long as possible. For example, in Chicago in 1908, nurses were sent to neighborhoods with the highest death rates to discuss infant feeding with mothers. However, since health department officials believed the nonacculturation of immigrants was at the root of infant mortality, nurses were sent only into immigrant neighborhoods.73 In Minneapolis, led by Julie Sedgwick, chief of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Minnesota, public health workers met with every new mother immediately after the birth of her baby, and in the 9 months following delivery, to address any lactation‐related problems.73

Several historians have noted that although many of the interventions to improve milk quality were structural, nevertheless physicians at the time typically disagreed on whether the problem was due to poverty or maternal behavior. Brosco, in 1999, characterized this as a debate between physicians who “called for legislation to prohibit the sale of commercial baby foods and to sanction mothers who did not nurse their children”47 and physicians who “argued that insufficient family income rather than laziness or ignorance led mothers to stop breastfeeding.”47

Similarly, in 2007, Nathanson observed, “The construction of infant mortality as a problem of bad milk was attractive to public health officials.… It promised a simple prophylactic against infant deaths, obviating the need for the fundamental environmental and behavioral reforms that had proved so difficult to accomplish.”50

Health Education for Mothers

The emphasis on breastfeeding as a maternal issue was indicative of the remaining strand of efforts to reduce infant mortality, which viewed the key problem as being that women were ignorant of how to care for their children. This approach became more prominent in the early 20th century, because, as the historian Meckel concisely observed in his 1990 classic analysis of late 19th‐ and early 20th‐century US public health efforts to “save the babies,” once key structural interventions were implemented, for example, improved sanitation and milk pasteurization, the focus of infant welfare activity shifted from “milk reform to maternal reform.”72

Thus, mothers became the “first line of defense against childhood disease.”56 Health information centered on infant feeding, home hygiene, and maternal responsibility.56, 57 Mothers were taught about protecting their infants from diseases carried by flies, conveyed by their dirty hands, and transmitted through impure milk. Information was delivered by a variety of means: the Children's Bureau published pamphlets called Infant Care and Prenatal Care addressing how to look after children, and it widely disseminated information on proper clothing, frequent bathing, and good ventilation. In addition, “Better Baby” and “Baby Week” campaigns (which were supplemented by a Children's Year in 1918‐1919)79 were used to draw attention to infant health and included clinics for infant checkups; educational materials for nurses, doctors, and mothers; and newspaper columns on infant care. “Little Mothers” classes were begun in many cities to teach young girls the proper methods of infant care before they had children.47, 56, 86, 91 Nurses and community health workers provided information on home hygiene and infant feeding through door‐to‐door campaigns, at milk stations, and at health centers.78, 82, 91 Information was also delivered in oral or written form at clinics or dispensaries, infant feeding stations or milk depots, and hospitals.56, 57, 91 These efforts were coordinated through a range of institutions, the most essential of which was the national network of women's clubs, and also included state child hygiene or child welfare agencies.34 It is important to note that upper‐class families were more able to take advantage of these messages. Given inequities in access to education and literacy, health‐related information delivered via pamphlets, newspapers, and schools would have been inaccessible for many African American families and low‐income families.30, 56

Several contemporary historians have suggested efforts directed at shaping maternal behavior did contribute to reductions in infant mortality.34, 56 Yet, consonant with the dominance of eugenics in the 1920s in US academia, public health, and politics,79, 92, 93, 94 along with surging anti‐immigrant populism and policies (epitomized by the 1924 and 1927 Immigration Restriction Acts),81, 95, 96 many public health professionals and child welfare advocates embraced eugenic positions, and their treatment of African American and foreign‐born infants was shaped by racist and anti‐immigrant views.47, 79 Efforts to develop culturally sophisticated public health campaigns sought to explain American ideals of personal hygiene, disease avoidance, parenting, and personal conduct to immigrant communities.27, 79 Even so, as noted by Brosco in 1999, noteworthy debates occurred between those who believed mortality rates could be attributed to ignorance and poor parenting and those who argued that income, working long hours, poverty, and inequity were the primary causes of high child mortality. The former advocated for health education and parenting classes, while the latter for better labor standards and improved maternal nutrition.47 The implication is that even with the rise of individually oriented and often victim‐blaming approaches, advocates for structural interventions to reduce IMR continued to maintain a presence.

Then and Now: Comparing Infant Mortality Reduction Efforts in the US (1850‐1950) With Those in LMICs (2000‐2015)

In contrast to the early 20th‐century efforts to reduce IMR in the United States, our review of the contemporary literature on reducing infant mortality in LMICs indicates the field is far less focused on structural interventions and far more focused on interventions at the individual, household, and health facility level. The evidence that routinely receives the most attention highlights the relationship between infant mortality and (a) individual‐level maternal factors, including maternal mortality, maternal education, breastfeeding, birth spacing, and medical care before, during, and after pregnancy and (b) individual‐ and household‐level child factors, including household sanitation, child nutrition, medical care at and after birth, vaccination, and household socioeconomic factors. In both cases, there is an emphasis on curative interventions for specific diseases.19, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104 Discussions about the health impacts of large‐scale sanitation projects, institutional changes, civil registration, and public policy efforts to improve breastfeeding, whether past or present, are largely missing from this literature.

The contrast between these 2 approaches is captured by Table 2, which summarizes key factors in the US effort to reduce infant mortality and juxtaposes these with the approaches endorsed and recommended by donors and multilateral organizations in global policy documents, as well as the mainstream evidence base for early childhood interventions to prevent neonatal and infant mortality and improve infant health in LMICs.

Table 2.

Efforts to Address Infant Mortality in the United States (1850‐1950) and in LMICs (2000‐2015)

| United States, 1850‐1950 | LMICs, 2000‐2015a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Area | Structural | Individual/Household | Structural | Individual/Household/Health Facility |

| Sanitation |

|

|

|

|

| Civil and vital registration |

|

|

|

|

| Breastfeeding and milk purification |

|

|

None |

|

| Medical care |

|

|

|

|

| Vaccination |

|

|

|

|

| Health behavior | None |

|

None |

|

| New institutions and policies |

|

Global

|

||

| Other | None | None |

|

|

Sources: UNICEF, World Health Organization 201558; Every Woman Every Child 201559; Every Woman Every Child 201260; UN Commission on Life‐Saving Commodities 201561; The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health 201162; Guiteras et al. 201563; Arnold et al. 201364; Dangour et al. 201365; World Health Organization and UNICEF 201366; United Nations General Assembly 201518; World Health Organization 2014123; United Nations General Assembly 200068; Abbott 192346; Tisdale 193370; Shapiro 195042; Condran and Crimmins‐Gardner 197823; Gaspari and Woolf 198524; Combs‐Orme 198871; Meckel 199072; Preston and Haines 199121; Fee 199444; Preston 199641; Hetzel 195049; Brosco 199947; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 199926; Almgren et al. 200034; Fishback et al. 200138; Stern and Markel 200227; Wolf 200373; Markel and Golden 200431; Condran and Lentzner 200420; Cutler and Miller 200548; Nathanson 200750; Lee 200774; Moehling and Thomasson 201275; Stoll 201325; Alsan and Goldin 201576; Bhutta and Black 2013104; US Children's Bureau 191491; Darmstadt et al. 2014.15

aLMICs, low‐ and middle‐income countries. These are largely donor‐funded efforts to reduce infant mortality.

b13 commodities: oxytocin (postpartum hemorrhage); misoprostol (postpartum hemorrhage); magnesium sulfate (eclampsia and severe preeclampsia); injectable antibiotics (newborn sepsis); antenatal corticosteroids (ANCs) (preterm respiratory distress syndrome); chlorhexidine (newborn cord care); resuscitation devices (newborn asphyxia); amoxicillin (pneumonia); oral rehydration salts (diarrhea); zinc (diarrhea); female condoms; contraceptive implants; emergency contraception.

As Table 2 makes clear, many of the contemporary interventions that receive the most global endorsement for addressing infant mortality do not address root causes and do not include sanitation and birth registration as central to the goal of reducing the IMR. Several recent global documents illustrate these problems. The Global Action Plan for Pneumonia and Diarrhoea does not include the terms “sewage” and “sewer,” and the term “infrastructure” is used solely to describe strengthening the infrastructure to deliver vaccines.66 The emphasis instead is primarily on individual‐ and household‐level interventions, with the plan advocating chiefly for 2 initiatives. The first is exclusive breastfeeding with appropriate complementary feeding, vaccination, oral rehydration therapy (ORT), and demand creation for behavior change. The second is improvements in the access to—and use of—safe drinking water and sanitation, without discussion of what it will take to put in place appropriate sanitation and water systems.66 The 2016‐2030 Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health likewise presents, as examples of interventions with high returns on investments in children's health, solely high quality of care at childbirth, immunization, breastfeeding, and early childhood development. Although the strategy acknowledged that around 50% of the gains in the health of women, children, and adolescents resulted from investments outside of the health sector and that interventions beyond the health sector should be core to infant health, nevertheless water and sanitation, education, air pollution, and birth registration were not included in the core list of interventions and instead were only mentioned as “multi‐sector enablers.”59

The same problems affect the prioritization and framing of the interventions listed in a 2014 global review of the key interventions related to reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH),105 which drew on global policy and peer‐reviewed literature, including the Lancet Child and Neonatal Series (2003 and 2005), to review 142 RMNCH interventions suitable for delivery through the health sector in LMICs.62 In this document, issues pertaining to infrastructure development, governance, and social development, along with recommendations for reducing inequality and ensuring fair working conditions, safe and affordable drinking water, and adequate sanitation, were relegated to a separate policy guide and not included in the primary document.105 In 2012, the UN Commission on Life‐Saving Commodities for Women and Children defined the barriers to the distribution and use of 13 low‐cost, high‐impact commodities solely at the individual level, with the key obstacles described as “poor compliance by health workers,” “poor understanding of products by mothers/caregivers,” and “limited awareness and demand.”60 Similarly, the 2014 Lancet Every Newborn Series examined progress on preventing neonatal deaths since 2005 with no discussion of the wider history of such efforts. Although the importance of birth registration was discussed,106 the series advanced a commitment to scaling up a package of services at both facility and community levels15, 107 and listed skilled birth attendants, antenatal care visits, female literacy rates, and total fertility rates as contextual factors.16 The priorities of the Every Newborn Action Plan, developed as part of the Lancet Series, referred primarily to several packages of interventions for both women and babies delivered along the continuum of care and argued that such an approach would have “the highest impact on saving lives and improving health outcomes.”67 Although improving birth and death registration is a strategic goal, the plan refers peripherally to sanitation as an “intersectoral goal.”67

Strikingly, most global targets, policy documents, and declarations are ahistorical and do not engage with the history of past eras’ successes in reducing infant mortality. Attesting to the lack of historical grounding, scant analysis exists that compares the costs of investing in behavior change, medical technology, and vaccination in perpetuity to investments in improving the infrastructure to register births, provide clean water, and improve access to primary care. Moreover, estimates of infant and child mortality in many countries remain elusive: notably, the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation and the Maternal and Child Epidemiology Estimation group differ in their estimates for the causes of child death, especially for malaria and AIDS,100, 108, 109 making it challenging to monitor infant mortality and rely on a single set of estimates to guide policy and planning.108

We now turn to whether tensions between individual and structural interventions exist in the context of global policies and programs specifically for sanitation, civil registration, and breastfeeding to address infant mortality in LMICs.

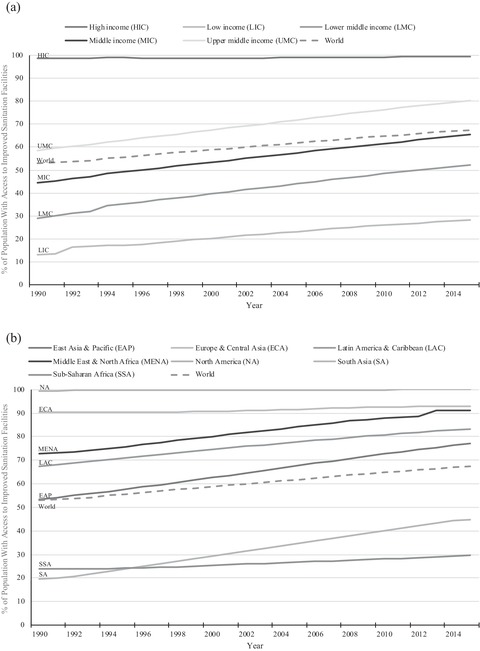

Sanitation

In the case of sanitation, the most recent UN estimates suggest 2.3 billion people lack a basic sanitation service (defined as improved facilities that are not shared with other households) and 844 million people are unable to access a basic drinking water service (defined as drinking water from an improved source, provided collection time is not more than 30 minutes for a round‐trip, including queuing).111 Exemplifying the problem, a recent analysis for sub‐Saharan Africa of the coverage of the SDG sanitation target (defined as improved water with a collection time of under 30 minutes, plus sanitation and a hand‐washing facility with soap) estimated that basic SDG coverage was only 4% and 921 million people lacked access.112 By comparison, the regions of North America, Europe, and Central Asia had achieved almost complete access to improved sanitation by 1990 (Figure 3). Although South Asia had the largest gain in access to sanitation between 1990 and 2015, nevertheless only 44.8% of the population had access to improved sanitation in 2015. Both South Asia and sub‐Saharan Africa remained below the global average of 67.5%.4

Figure 3.

Access to Improved Sanitation Facilities in Countries, Stratified by (a) Income Group and (b) Region (1990‐2015)

Access to improved sanitation facilities refers to the percentage of the population using improved sanitation facilities. Improved sanitation facilities are likely to ensure hygienic separation of human excreta from human contact. They include flush/pour flush (to piped sewer system, septic tank, pit latrine), ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrine, pit latrine with slab, and composting toilet.

Data derived from the World Bank 2015.4

The role of public health professionals and institutions in building large sewage or water filtration systems is very different in the current global health context compared to the United States at the turn of the 20th century. Although there is agreement that access to good sanitation and clean water can prevent infant mortality, undernutrition, and diarrhea98, 113, 114, 115, 116 (see Table 2), structural sanitation and hygiene interventions are not central to current mainstream public health interventions designed to avert infant mortality in LMICs.

Studies have found that even though piped water and connected toilets are initially much more expensive than low‐tech sanitation technologies, the average cost per life year saved turns out to be roughly the same due to the longer durability and superior health impact associated with the higher‐end technologies.114 For example, in a 2011 analysis of 171 household surveys, Gunther and Fink found strongly protective effects of high‐quality toilet facilities for the risk of mortality, episodes of diarrhea, and stunting. They demonstrated that the average mortality reduction achievable by investment in water and sanitation infrastructure was 25 deaths per 1,000 children born across countries, and full household coverage with water and sanitation infrastructure could lead to a total reduction of 2.2 million child deaths per year in the developing world.114

Nevertheless, even efforts to promote the adoption of effective, low‐cost improvements to water quality and sanitation have been largely unsuccessful,113 and a greater focus has been placed on addressing diarrhea and stunting directly (see Table 2). For example, in 1978, an editorial in The Lancet called ORT “potentially the most important medical advance of the 20th century,” and since that time approximately a million lives per year have been saved by ORT.25 However, a status quo in which ORT is used as a permanent substitute for clean water and sanitation systems has become acceptable,117 and the interventions currently used in LMICs to improve sanitation described in Table 2 operate largely at the individual or household level, concerned with the provision of commodities and with education and behavior change. Exemplifying this orientation, the MDG target did not include any consideration of the need for sanitation in schools, workplaces, and public places.65 Even if the WHO sanitation target had been met, 1.6 billion people would still lack even a simple “improved” latrine at home (defined as flush/pour flush to piped sewer system, septic tank, or pit latrine; ventilated improved pit latrine; pit latrine with slab; or composting toilet),36 suggesting that many of the global targets are inadequate. Similarly, even if the WHO drinking water target had been reached in 2015, 800 million people would have been living in homes where water is collected from distant or unprotected sources.118

Civil Registration

Major problems likewise remain with regard to adequate civil registration, including of births, which is vital to ensuring good data for allocating resources to reduce the IMR. Instead, the attention of governments in many LMICs is being directed toward creating biometric identification systems (see Table 2). Conservative estimates suggest that 80 countries have biometric identification programs and more than 1 billion people in LMICs have had their biometrics recorded, and this number is growing.119 Most recently, the 2016 World Development Report advocated for identification systems as a way to address the significant number of children and adults without any form of identification document.120 However, the purpose of biometric identification systems is to authenticate individual identity, and they do not always confer rights and privileges associated with birth registration,121 nor are they mandated to be connected to civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) systems.

Investments in digital identification systems without improving or linking new identification systems to civil registration cost governments the ability to monitor and act upon important public health data, including the infant mortality rate. This is taking place even though the benefits of birth registration are well described, including integrating birth registration with other child health interventions.122 Both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention of the Rights of the Child, as well as the Commission on Information and Accountability for Women's and Children's Health,123 underscore the importance of legal identity and civil registration and vital statistics systems. Additionally, the SDGs aim to improve the “proportion of children under five years of age whose births have been registered with a civil authority” (SDG 16.9).18

However, pointing to large gaps in civil registration, in 2015, using data from 198 economies, the World Bank estimated that around 1.8 billion people lacked legal identity, with the largest number in South Asia. Slightly less than half of these people are children.124 A study using data from 94 countries between 2000 and 2014 showed that birth registration remained lowest in Eastern and Southern Africa, West and Central Africa, and South Asia.125 As discussed in two Lancet series on civil registration in 2007 and 2015,126, 127 weak vital registration systems in LMICs deny children and adults the benefits associated with registration, such as accessing government programs, traveling, opening a bank account, and proving family relationship, and also undermine capacity to generate the local data needed to guide public policy and resource allocation, a data need that cannot be met by surveillance based solely on national surveys or sentinel sites.127 Interventions to improve birth registration include implementing registration campaigns in communities, improving access to registration for children born in health facilities, using mobile technology, and digitizing birth records.

Breastfeeding

Another striking facet of the literature is that despite the proliferation of global and national agencies with targets focused on reducing IMR19, 59, 60, 66, 67, 128, 129 (see Table 2), the scope of the proposed initiatives remains primarily focused on changing the behavior of individuals, especially mothers, as exemplified by the case of current interventions focused on breastfeeding and milk purification. In brief, many studies describe the benefits of breastfeeding for infant and maternal health and attribute breastfeeding a role in decreasing infant mortality.66, 101, 130 A Lancet series concluded that breastfeeding was one of the top interventions for reducing under‐5 mortality and suggested that the modest changes in breastfeeding rates since 2000 contributed to the fact that most LMICs did not reach the MDG infant mortality targets. However, current global discourses on breastfeeding overwhelmingly recommend education for mothers in health facilities and during postnatal visits, and few laws are in place to enable and protect the employment and work conditions that allow women to breastfeed. Although some countries have enacted policies on milk purification, implementation of the International Code on Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes is not a substitute for structural interventions addressing economic obstacles to women breastfeeding.130

Why History Matters in Current Efforts to Address Infant Mortality

As should be apparent, current approaches to reducing infant mortality endorsed by global policy documents and public health research are not informed by relevant historical evidence. Perhaps the current focus in LMICs on individual behavior would be understandable if research demonstrated that the relevant structural interventions have already been implemented or else that structural interventions would not be as effective as the interventions oriented toward individual behavior. This would be analogous to what occurred in the United States, starting in the 1910s, once structural reforms involving sanitation, milk pasteurization, and civil registration were either completed or well under way. However, the current literature does not support such an interpretation and instead makes clear that structural reforms to address infant mortality were never the priority of global policies or interventions.

The historical context of the current commitment in LMICs to an IMR reduction strategy that focuses on smaller‐scale interventions targeted primarily at individuals, households, and health facilities is important. Table 3 contextualizes the evidence base and policy goals underpinning global health efforts to address infant mortality and provides a broad chronology of the creation of global institutions to address infant mortality following World War II, which is characterized by a shift away from more comprehensive, broadly based community health programs toward more narrowly defined technological interventions.8, 131

Table 3.

Timeline of Key Milestones and Shifts in Global Health Priorities Pertaining to the Reduction of Infant Mortality

| Year | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 1944 | UN Monetary and Financial Conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, establishes the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank) |

| 1945 | United Nations is established |

| 1946 | United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) founded |

| 1946 | First meeting of the board of the World Bank |

| 1948 | Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO) ratified by the first World Health Assembly |

| 1959 | World Health Assembly commits to a global smallpox eradication program |

| 1974 | WHO creates the Expanded Programme on Immunizations |

| 1974 | Alma‐Ata Declaration articulates the goal of primary health care and of achieving health for all by 2020 |

| 1969 | World Health Assembly declares it was not feasible to eradicate malaria |

| 1977 | Eradication of smallpox |

| 1980s | World Bank Structural Adjustment Programs |

| 1982 | UNICEF launches child survival agenda, which focused initially on 4 interventions: growth monitoring, oral rehydration, breastfeeding, and immunizations (GOBI) |

| 1984 | Bellagio conference in Bellagio, Italy. Those in attendance included the president of the World Bank, the vice president of the Ford Foundation, the administrator of USAID, and the executive secretary of UNICEF. Focus on “selective Primary Health Care,” with the goal of delivering pragmatic, low‐cost interventions, which were articulated as GOBI. Conference led to the formation of the Task Force for Child Survival, which included UNICEF, WHO, UNDP, the World Bank and the Rockefeller Foundation, and agreement on Jim Grant's goal of immunizing 80% of the world's children against 6 major diseases by 1990 |

| 1990 | World Summit for Children, New York. Led by 71 heads of State and Government and 88 other senior officials, mostly at the ministerial level. Nations commit to a target of 70 deaths per 1,000 live births for children under 5 |

| 1995 | Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) program created |

| 2000 | Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) created |

| 2000 | Save the Children launches its Saving Newborn Lives program funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation |

| 2000 | Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) established |

| 2005 | The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH) is founded |

| 2005 | Lancet Neonatal Survival Series published |

| 2005 | Countdown to 2015 created as a multi‐institutional effort to track progress on the health‐related MDGs with PMNCH as the secretariat |

| 2010 | United Nations Millennium Development Goals Summit; UN Secretary‐General Ban Ki‐moon launches Every Woman Every Child |

| 2012 | World Health Assembly endorses Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) |

| 2014 | WHO develops the Every Newborn Action Plan; WHO and UNICEF develop the integrated Global Action Plan for Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD) |

| 2015 | Sustainable Development Goals established |

| 2016 | 2016‐2030 Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health |

Evidence indicates this shift away from community development toward technological “fixes” has led to substitution effects in morbidity and mortality; for example, children were saved from measles and diarrhea only to die from causes not covered by these interventions.3 Although the elements of GOBI—growth monitoring, oral rehydration, breastfeeding, and immunizations—dramatically reduced child mortality across LMICs by 1990, this was at the expense of efforts to strengthen health services, to address a wide range of health issues that could not be eliminated through immunizations, and to improve water and sanitation.6 In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness program delivered narrowly focused vertical interventions, which did not consider contextual factors.97, 132 More recent efforts have tried to strengthen health systems133 and build a continuum of care that functions effectively to meet the needs of women and children.67, 108, 132 The 2008 WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, led by Sir Michael Marmot,7 deepened global awareness of and commitment to the importance of changing contexts and structures and underpins the renewed thrust of WHO work on health in all policies and the SDGs relating to health.

Shiffman draws on social constructivism to suggest that issues and claims considered important are related to the “effectiveness of global health policy communities in portraying and communicating severity, neglect, tractability and benefit in ways that appeal to political leaders’ social values and concepts of reality.”134 In Tables 2 and 3 we show that the growing financial, political, and programmatic commitment to child survival13, 14, 17 has entrenched an emphasis on the widespread adoption of a small number of cheap, ostensibly accessible, and simple technologies, often at the cost of leaving the wider conditions that determine child survival largely untouched.