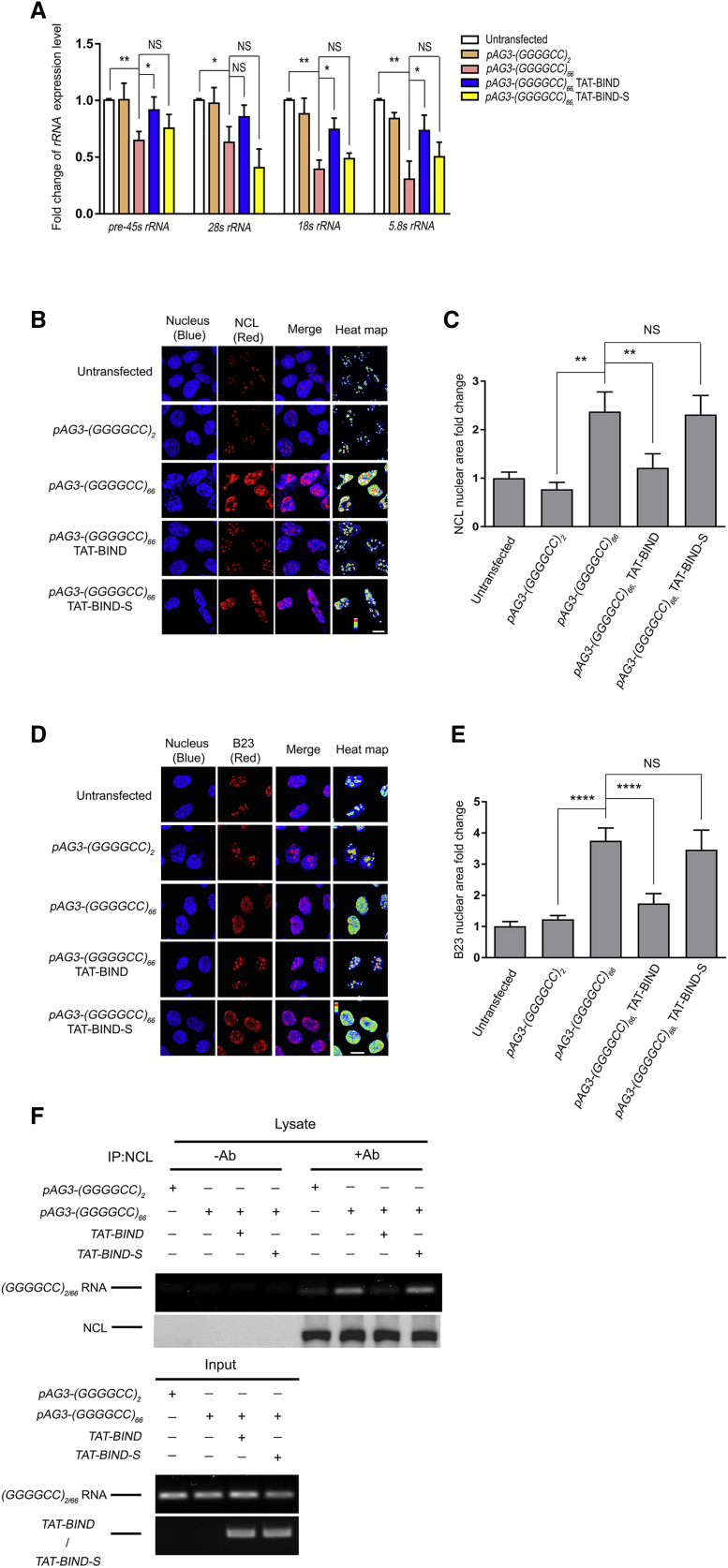

Figure 3.

TAT-BIND Treatment Suppressed Nucleolar Stress in pAg3-(GGGGCC)66-Expressing SK-N-MC Cells

(A) TAT-BIND rescued impaired rRNA transcription in pAg3-(GGGGCC)66-expressing cells. (B) TAT-BIND inhibited the mislocalization of NCL proteins in pAg3-(GGGGCC)66-expressing cells. (C) Statistical analysis of the nuclear NCL fold change of (A). (D) TAT-BIND inhibited the translocation of B23 protein from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm in pAg3-(GGGGCC)66-expressing cells. (E) Statistical analysis of nuclear B23 fold change of (C). (F) TAT-BIND disrupted the interaction between expanded GGGGCC RNA and NCL. For (A), total RNA was extracted followed by reverse transcription. Real-time PCR was employed to determine the expression level of corresponding rRNA. Actin was used for normalization. Fold change of gene expression level was compared to untransfected cells. For (B)–(E), the cells were subjected to immunofluorescence using anti-NCL or anti-B23 antibody (red). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33343 (blue). The heatmap of NCL or B23 intensities highlighted the differences of protein localization among the cells. The scale bars indicate 10 μm. The pixel area of the NCL relative to the area of the nucleus was calculated and normalized to that of the untransfected control. 150–300 cells were measured for each condition. For (F), cells expressing pAG3-(GGGGCC)2/66 RNA were co-transfected with either the pcDNA3.1(+)-TAT-BIND-myc or pcDNA3.1(+)-TAT-BIND-S-myc construct. Endogenous NCL protein was immunoprecipitated with anti-NCL antibody, followed by RT-PCR to determine the presence of GGGGCC2/66 RNA. “+” indicates the presence of anti-NCL antibody in the immunoprecipitants, while “−” indicates that anti-NCL antibody was not included. All experiments were repeated at least thrice with consistent results. Data were plotted as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001; NS, no significance.