Abstract

Background:

Road traffic injuries are a leading cause of death and disability. In low and middle income countries, vulnerable road users are commonly involved in crashes with severe injuries. This study describes the epidemiology and built environment analysis of road traffic crashes and hot spots in Galle, Sri Lanka.

Methods:

After ethical and police permission, police data was collected and descriptive statistics tabulated. Spatial analysis was performed to identify hot spots and BEA was conducted at each location.

Results:

752 crash victim data from 389 reported road traffic crashes were collected. Most victims were male (91%) 21-50 years of age (>70%). 49% of the crashes were non-grievous. Crashes commonly included motorcycles (33.9%), three-wheelers (18.3%) or cars (14.4%). Most victims were drivers (130 of 389, 33.4%) or pedestrians (83 of 389, 21.3%). Factors contributing to the crash include: aggressive driving (173 of 389, 44.5%) or speeding (166 of 389, 42.7%). All hotspots were in urban areas, and most were at intersections (63%).

Conclusions:

In Galle, Sri Lanka, most road traffic victims were 21-50 year old males and vulnerable road users. Further analysis of these hot spots are necessary to identify areas for intervention for each type of road user and intersection.

INTRODUCTION

Road traffic injuries are a major public health problem globally. About 1.2 million people are killed and more than 50 million are injured due to road traffic crashes annually.{Peden M, 2004 #60} More than 90% of these deaths and injuries occur in low and middle income countries (LMIC) due to rapid motorization, lack of road safety culture, poor road conditions, and lack of education on road safety.{, 2013 #879} In LMIC, injuries due to road traffic crashes are the 4th leading cause of death in the economically active age group (18-45 years of age).{Peden M, 2002 #91} It has been forecast that deaths and injuries due to road traffic crashes will increase by 65% from 2000 to 2020 worldwide especially among LMIC like Sri Lanka. {Kopits E, 2003 #941}{Murray CJ, 1996 #208}.

Sri Lanka has experienced exponential growth of motorization since 1977. Its open economic policies in the setting of an underdeveloped road infrastructure has caused an immense burden of road traffic crashes. Since 2003, while total crashes appear to have decreased, road traffic fatalities have not shown a similar reduction.{Dharmarathne SD, 2013 #943} In 2003, major motor insurance companies started the scheme of on the spot compensation payments to the owners of damaged vehicles without police reports, and as such this apparent decrease in road traffic crashes is likely due to under reporting of non fatal crashes {Dharmarathne SD, 2013 #943}{Periyasamy N, 2013 #859}. Still, police reports remain the main available source for evaluation of road traffic crashes in Sri Lanka.

In Sri Lanka, there are approximately 2000 deaths and 20,000 injuries per year due to road traffic crashes.{Police, 2010 #942} Police statistics (2011) found the most common vehicles involved included motorcycles, cars, and three wheelers, with 45% of road traffic fatalities being either vehicle drivers or riders and almost 33% being pedestrians.{Police, 2010 #942} Almost 80% of the victims were in the economically productive age group. The number of road traffic crashes increased from 61.2 to 195.9 per 100,000 populations from 1938 to 2011.{Dharmarathne SD, 2013 #943}

The objective of this ecological study was to describe the epidemiology and map the location of hot spots of road traffic crashes within the Galle Municipality area, Sri Lanka. With further information regarding road traffic victims, types of road users, and the location and timing of crashes, we hope to increase public awareness and also to provide better data for police and policy makers, allowing for safety interventions to minimize road traffic crashes.

DEMOGRAPHICS

This study was conducted in the urban area of the Galle district, Galle Municipality area, in the southern province of Sri Lanka. It has an approximate population of 100,000 people. The ethnic composition comprises 66.6% Sinhala, 32.3% Muslim, 0.8% Tamils and 0.3% others - mainly including Burghers and Malays. There are two police stations within the Galle municipal area: Galle City police station and Galle Port police station. All road traffic crashes in the Galle municipality area reported to these two police stations were included in the current analysis.

METHODS

Ethics Approval

This project was approved by the Ethical Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna in Sri Lanka and by the Duke University Institutional Review Board, USA.

Variables

The main variable studied was the geographic location of crashes in the Galle Municipality area during 2013. Crash location was determined by the latitude and longitude of the crash point.

Crash severity was categorized according to the most serious injury to any person taking part in the crash: damage only (no injuries, vehicle damage only), non-grievous injury, grievous injury and fatal crashes (one or more persons died due to the crash) taken directly from the police records. The severity of the crash was further dichotomized into non-grievous (no injuries and non-grievous) and grievous (grievous and fatal) crashes for bivariate and multivariate analysis. Other characteristics of the crash included: day of the crash (weekend or weekday), time of the crash (daytime or night time), type of the vehicles involved in the crash and the road conditions such as double or single lane road and whether the road was dry or wet. Characteristics of individual crash victims included age, gender and crash severity. The role of the participant in the crash, such as driver, rider or pedestrian was collected by the police data for only one member of the crash.

Data Collection Methods

We collected data on road traffic crashes reported to the Galle City police station and Galle Port police station from the Galle municipality area. In the police stations, all the data on the crashes were manually entered into a specifically designed form and filed with the officer in-charge of traffic police.

After ethical clearance was provided, permission was obtained from the Deputy Inspector General of Police for the southern range of Sri Lanka to collect necessary information from the above police records. Then all the data was retrospectively extracted from the police records for 12 months from the 1st of January 2013 to the 31st of December 2013 by the investigators.

Data Analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Duke University.{Harris, 2009 #902} REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources. Data analysis included frequencies and tabulations and was performed using STATA (StataCorp, College Station TX 2014). Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models were conducted to evaluate the association between crash characteristics (e.g. road characteristics, time of day) and gravity of crash (Grievous vs. Non-grievous).

Spatial Analysis

An exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) was used with a point process framework to identify locations with the highest frequency of traffic crashes, ie, the hot spots through map visualization.{Anselin L, 1998 #927} By understanding the spatial distribution of these crashes, we evaluated the point patterns for a random distribution or clustered locations.{Waller L, 2004 #928} The georeferenced cartographic database of the Galle municipality is freely available online in SHP format (shapefile) at the Department of Census and Statistics of Sri Lanka (http://www.statistics.gov.lk/).{, 2013 #541} We utilized the Kernel Density Estimator to create a point density map (raster image) through heatmap plugin in Quantum GIS (QGIS) software, open source, version 2.2.{Quantum GIS Geographic Information System, 2014 #914} This estimator establishes a two-dimensional function of events, forming a surface whose value is proportional to the intensity of samples per unit of area, so-called “hot spots”.{Camara G, 2002 #929}{Bailey TC, 1995 #930} Thus this function performs a count of all points within a region of influence, weighting them by the distance of each point to the location of interest.{Waller L, 2004 #928}{Camara G, 2002 #929}{Bailey TC, 1995 #930}Also, we used a field weight which allows for certain locations to be more heavily weighted in the resultant heatmap; in our case crash locations were weighted by the severity of injury.

Built environment characteristics

Using the hotspots locations identified previously, we collected data on the built environment characteristics of each hotspot using a standardized instrument for road traffic crashes BEA. Research assistants went to each hotspot location and filled in the instrument using RedCAP. Hotspots determined by spatial analysis were further analyzed and characteristics recorded, including road design, intersections, number of lanes, condition of the pavement, presence of auxiliary lanes, type of road narrowing and shoulder hazards, signage, speed limits, pedestrian traffic, use of helmets, visibility limitations, bridges and use of headlights.

This instrument evaluates BEA in 5 domains regarding: Urban characteristics, Rural characteristics, Motor vehicle density, Built road safety and Built pedestrian safety. Values are area standardized in a 0 to 100 scale, where 0 means low score and 100 means high score on each domain.

Initially we describe the built environment characteristics for the hotspots using descriptive statistics. In sequence, a cluster analysis was used to identify groups of hotspots that were similar according to the BEA domains. After the clusters were found, we compared the scores that characterized the built environment of each cluster and evaluated the cluster’s association with the risk (High or Low risk for RTI/RTC) for crashes at each hotspot. Cluster analysis was conducted with K-means using the software R Language for Statistical Computing v.3.01.

RESULTS

In total there were 752 crash victims from 389 road traffic crashes. Most of the victims were male (673 of 738, 91.2%); there was missing information about gender for 14 of the victims. Over 70% of the road traffic victims were between the ages of 21 and 50 as seen in Table 1. Over half of the road traffic crash victims (485 of 752, 64.5%) were attended to at the local hospital.

Table 1:

Crash / primary victim factors associated with grievous injury by bivariate analysis;

| Grievous | Non-Grievous | Unadjusted OR (IC95%) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean/sd) | 40.14 (16.01) | 39.34 (13.42) | 1.00 (0.99;1.02) | .558 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 113 (86.92) | 530 (91.69) | - | ||

| Female | 17 (13.08) | 48 (08.30) | 0.60 (0.33;1.09) | .091 | |

| Day of Week | |||||

| Sunday | 9 (06.92) | 66 (11.15) | - | ||

| Monday | 17 (13.85) | 70 (11.82) | 1.89 (0.79;4.49) | .152 | |

| Tuesday | 13 (10.00) | 99 (16.72) | 0.96 (0.39;2.38) | .935 | |

| Wednesday | 26 (20.00) | 103 (17.40) | 1.85 (0.82;4.20) | .140 | |

| Thursday | 14 (10.77) | 75 (12.67) | 1.37 (0.56;3.37) | .494 | |

| Friday | 24 (18.46) | 93 (15.71) | 1.89 (0.83;4.33) | .131 | |

| Saturday | 26 (20.00) | 86 (14.53) | 2.22 (0.97;5.05) | .058 | |

| Light Condition | |||||

| Daylight | 89 (69.53) | 436 (77.58) | - | ||

| Dusk/Dawn | 12 (09.37) | 46 (08.18) | 1.28 (0.65;2.51) | .476 | |

| Night/Improper Light | 6 (04.69) | 14 (02.49) | 2.10 (0.79;5.61) | .139 | |

| Night/Good LIght | 21 (16.41) | 66 (11.74) | 1.56 (0.91;2.68) | .108 | |

| Type of Vehicle | |||||

| Pedestrian | 22 (17.18) | 59 (10.05) | - | ||

| Cycle | 8 (06.25) | 23 (03.92) | 0.93 (0.36;2.39) | .885 | |

| Motorcycle | 49 (38.28) | 183 (31.17) | 0.72 (0.40;1.29) | .265 | |

| Cars | 12 (09.37) | 90 (15.33) | 0.36 (0.16;0.78) | .009* | |

| Tuk-Tuks | 16 (12.50) | 88 (14.99) | 0.49 (0.24;0.99) | .051* | |

| Trucks | 21 (16.40) | 144 (24.3) | 0.39 (0.20;0.76) | .006* | |

| Weather | |||||

| Clear | 122 (95.31) | 563 (98.59) | - | ||

| Rain | 4 (04.79) | 4 (02.41) | 4.46 (1.14;18.71) | .032* | |

| Zone | |||||

| Urban | 70 (53.85) | 323 (55.12) | - | ||

| Rural | 60 (46.15) | 263 (44.88) | 0.95 (0.65;1.39) | .792 | |

| Type of Road | |||||

| Single | 75 (57.69) | 356 (60.34) | - | ||

| Two Lanes | 55 (42.30) | 234 (39.66) | 1.12 (0.76;1.64) | .577 | |

| Speed Signs* | |||||

| Yes | 52 (59.05) | 209 (64.15) | 1.24 (0.84;1.84) | .281 | |

| No | 75 (40.95) | 374 (35.84) | - | ||

| Traffic Control* | |||||

| Yes | 19 (14.61) | 176 (29.73) | 0.40 (0.24;0.68) | .001* | |

| No | 111 (85.38) | 416 (70.27) | - | ||

| Type of Junction | |||||

| Yes | 46 (40.35) | 196 (41.18) | 0.97 (0.64;1.47) | .872 | |

| No | 68 (59.64) | 280 (58.82 | - | ||

| Human Factors | |||||

| Aggressive Driving | 29 (22.31) | 212 (35.81) | - | ||

| Speeding | 47 (36.15) | 142 (23.98) | 2.42 (1.45;4.03) | .001* | |

| Other/Unknown | 54 (41.54) | 238 (40.21) | 1.66 (1.02;2.70) | .004 | |

| Alcohol Use | |||||

| Yes | 4 (03.08) | 21 (03.55) | - | ||

| No | 76 (58.46) | 313 (52.96) | 1.27 (0.43;3.82) | .665 | |

| Not tested | 50 (38.46) | 257 (43.48) | 1.03 (0.34;3.10) | .970 |

significant in the multivariate model

Of the 389 total crashes, 49% were characterized as non-grievous, while only 3.9% were fatal crashes. (Table 1). Most crashes occurred in January and April with the lowest number of crashes occurring in August, September, and October. The highest number of crashes occurred on Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday. Most crashes happened during clear (368 of 373, 98.7%) or dry (365 of 373, 97.9%) weather on single lane roads (238 of 388, 61.3%) and during daylight (284 of 371, 76.6%). Most commonly crashes included motorcycles (33.9%), three-wheelers (18.3%) or cars (14.4%). Of the data collected for the primary victim of the crash, most victims were drivers (130 of 389, 33.4%), pedestrians (83 of 389, 21.3%) or passengers or pillion rider (30 of 389, 7.7%). Factors contributing to the crash according to the police records included: aggressive driving (173 of 389, 44.5%), speeding (166 of 389, 42.7%), drugs alcohol or fatigue (6 of 389, 1.6%).

In the bivariate analysis, factors that decreased the risk of grievous events were being in a tuk tuk, car or truck, or being at a location with traffic control. Those factors which increased the risk of grievous events were rain, speeding and ‘other or unknown human factors.’ All these factors remained significant in the multivariate model except for the ‘other or unknown human factors.’

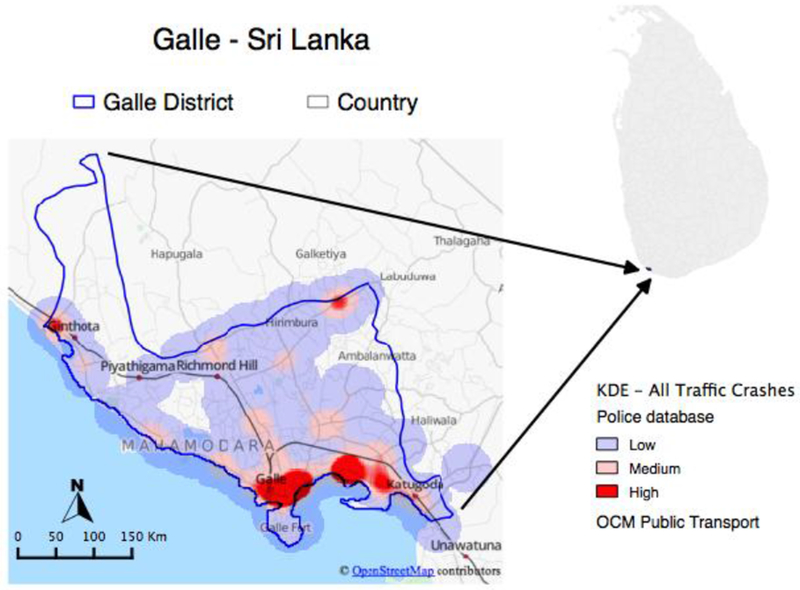

The road traffic crash hot spots are displayed in Figure 1 by the Kernal Density Estimator. The locations of road traffic crashes by crash severity are highlighted in Figure 2A and 2B. In Figure 3A-F, the road traffic crashes are presented by type of road user whereas Figure 4 highlights the hot spots for road traffic crashes comparing minor injuries to fatal or grievous injuries.

Figure 1:

Policy Data Crashes Kernel Density Analysis of High, Medium and Low Density areas of All Types of Road Traffic Crashes

Figure 2A and 2B:

Road Traffic Crash Locations by Severity of Crash; A. Galle Municipality B. Galle City Center

Figure 3A-F:

Comparison of the Kernel Density Estimation of Medium and High Density Hotspots of A) Pedestrians, B) Bicyclists, C) Motorcyclists, D) Tuk-Tuks, E) Cars, F) Trucks

Figure 4A-B:

Hotspots of Crashes by A) Minor Injuries B) Fatal/Grievous Injuries

Built environment characteristics of hot spots are listed in Table 2. All hot spots were located in urban areas and full paved local streets, mostly intersections (63.0%), with cars turning to both left and right (59.8%), and one lane roads (50.8%). Presence of risks along the road included narrowing (57.5%), lack of median separation (89.8%) and dangerous elements on the side of the road (99.0%). Most of the roads had shoulders (63.0%) and only a few showed unevenness (6.8%). Almost a third of the hot spots were in curves or hills areas (28.3%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description and association of built environment characteristics and risk classification of road traffic hot spots in Galle, Sri Lanka.

| BEA Characteristic | Total |

|---|---|

| Road/Street Conditions, N (%) | |

| Urban X Rural | 127 (100) |

| Local streets X Highway | 127 (100) |

| Presence of intersections | 80 (63.0) |

| Cars in the same direction | 12 (9.4) |

| Cars turning left or right | 76 (59.8) |

| Heavy pedestrian traffic | 23 (18.1) |

| One X Two Lanes | 64 (50.8) |

| Full paved roads | 126 (99.2) |

| Road narrowing | 73 (57.5) |

| Road side shoulder | 80 (63.0) |

| Road side danger | 126 (99.2) |

| Road side Unevenness | 8 (6.3) |

| Road Median Separation | 13 (10.2) |

| Environment/Built Conditions, N (%) | |

| Walkways | 42 (33.3) |

| Bus stop | 31 (24.6) |

| Speed bump | 4 (3.1) |

| Traffic Signs | 1 (0.8) |

| Speed Limit | 127 (100) |

| Curves and Hills | 36 (28.3) |

| Good street lighting | 66 (52.4) |

| Traffic Density, Median (IQR) | |

| Car | 6.0 (3.0;9.5) |

| Buses/Trucks | 4.0 (1.0;8.5) |

| Bikes | 3.0 (1.0;5.5) |

| Motos | 19.0 (12.0;27.5) |

| Tuk Tuks | 8.0 (4.0;12.0) |

| Pedestrians | 2.0 (0.0;4.0) |

As for built safety infra-structure, only a third of the hot spots showed walkways (33.3%), and very few had bus stops (24.6%), speed bumps (3.1%) or traffic lights (0.8%). All hot spots had speed limit signings, and most had good streetlights (52.4%). The density of motorcycles and Tuk-Tuks was higher than other methods of transportation across hot spots (Table 2).

Hot spots classification showed three clusters marked by differences in their road structure, density of motor vehicles and built road or pedestrian safety characteristics (Table 3). Cluster A referred mostly to rural characteristic roads (highways) with more built safety features like road signs and less MVC density than the other Clusters. Cluster B was mainly urban but with higher road safety conditions and MVC density than Cluster A (e.g. downtown areas). Cluster C has similar characteristics to Cluster A, but with less safety conditions and more motor vehicle densities. All clusters had low pedestrian safety characteristics. The association of built environment clusters with risk for RTC/RTI in Galle did not show any increased risk to be of high risk for RTC/RTI than Cluster A (Table 1).

Table 3.

Built environment clusters characteristics and association with risk classification for RTC/RTI.

| Cluster A | Cluster B | Cluster C | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban characteristics, Mean (SD) | 56.4 (49.7;63.2) | 63.2 (56.5;63.2) | 56.4 (49.7;63.0) | 0.03 |

| Rural characteristics, Mean (SD) | 14.6 (1.4;21.0) | 7.8 (6.4;13.7) | 19.6 (7.8;27.1) | 0.04 |

| Built road safety, Mean (SD) | 13.2 (13.2;35.5) | 13.2 (13.2;13.2) | 0.0 (0.0;0.0) | >0.01 |

| Road MV density, Mean (SD) | 22.2 (12.2;24.9) | 44.6 (33.3;49.9) | 30.1 (18.3;50.1) | >0.01 |

| Built pedestrian safety, Mean (SD) | 2.6 (1.2;4.3) | 5.4 (3.5;14.8) | 2.9 (0.1;6.2) | 0.02 |

| Risk area for RTC/RTI, OR (CI 95%) | Ref | 0.62 (0.15;2.58) | 0.61 (0.19;1.78) |

DISCUSSION

This analysis is the first combination of an epidemiologic overview and spatial analysis of road traffic crashes in a low and middle income country; it was also the first in depth road traffic crash spatial analysis in Sri Lanka. Our analysis showed that most road traffic crash victims were male (91%), between the ages of 21 and 50 (>70%), and on motorcycles (34%) or three-wheelers (18%). Almost half (49.0%) of the reported crashes had a non-grievous injury, 13.7% had grievous injury, and only 3.61% crashes were fatalities. Crashes were due to aggressive driving (45%) or speeding (43%), and 65% sought care for their injuries at a local hospital. Risk factors for more grievous injury were speed and rain while protective factors were being in a tuk-tuk, car or truck (compared to pedestrian), and having traffic control. While human behavior can impact crash occurrence, the road environment influences both human behavior as well as crash severity and risk.{Peden M, 2004 #60} Road traffic crash hot spots were identified in preparation for road safety audits for interventions to reduce the burden of road traffic crashes.

Our study found a male predominance of victims (91%) - this is similar but markedly higher compared to other data internationally (73%) and in Sri Lanka (77.9%).{Peden M, 2004 #60}{Periyasamy N, 2013 #859}This difference may be due to fewer female drivers or riders in the Galle community and/or reluctance of females to report the crashes to the police. Similarly, our finding of a preponderance of crash victims in the 21-50 year age group (>70%) has been found both in other countries and and in Kandy, Sri Lanka where 58.4% of the victims were 25 to 49 years of age.{Periyasamy N, 2013 #859} In our study, motorcycles and three wheelers were most commonly involved in crashes (>50% of crashes) pedestrians were only 1.3% of our crash victims. While similar results about motorcycles and three-wheelers have been found in other areas of Sri Lanka, the lower proportion of pedestrians in our study suggests a difference in traffic environment between Galle and Colombo - in Colombo pedestrians are almost 40% of road traffic fatalities.{Peden M, 2004 #60}{Weerawardena WAK, 2013 #931} As expected being in a car or truck reduced your risk of grievous injury, but unexpectedly, tuk-tuks also are protective. Traditionally, tuk-tuks are a portion of vulnerable road users but their limitations of speed and some protection during a crash might make them safer in a crash than being a pedestrian. Interestingly, there was a very low involvement of alcohol or drugs (<1.6%) reported in police records as contributing to the crash in our study, while alcohol involvement has been as high as 32% in other hospital based data from Sri Lanka and even higher in other LMIC globally.{Peden M, 2004 #60}{Weerawardena WAK, 2013 #931}Anecdotally, in Galle, there is more of an alcohol problem than elsewhere in Sri Lanka, implying that there may be both limited testing and underreporting.

Spatial analysis identified numerous road traffic hot spots around the Galle City Center and within the Municipality. (Figure 1) Each of these hot spots, has been further highlighted in Figure 2B, and have crash locations that can be more thoroughly described for further interventions. As seen in Figures 4A and 4B, when separated by severity of injury, much of the same hot spots were identified. The spatial analysis elucidated specific locations that are more dangerous by type of road use, so built environment analysis was performed to further assess characteristics of risk. BEA found that all of the hotspots were in urban regions, and mostly at intersections (53%). This suggests that evaluations/interventions at specific high-risk intersections, regardless of the severity of the crashes reported there, would decrease both road traffic crashes as well as resulting injuries.

Limitations:

This study has two main limitations. First, our results are dependent on the quality of the police data collected, and there have been recent reports in Sri Lanka suggesting that there has been up to a 33% of under reporting of road traffic crashes in police reports.{Periyasamy N, 2013 #859} This underreporting may be due to recent insurance company policies allowing on-site settlement between crash victims without police reports. While Sri Lanka law mandates reporting fatal crashes to the police, Periyasamy found that 2 of 16 deaths were not identified in police records.{Periyasamy N, 2013 #859}There is also a hospital based police post in order to identify crashes amongst those who seek care at the hospital. Most of the unreported crashes have been found to be minor injuries or crashes without injuries.{Periyasamy N, 2013 #859} Knowing this limitation, we performed the analysis seen in Figure 4A and 4B looking at hot spots with Fatal/Grievous Injuries compared to Minor or no Injuries to limit the impact of potential underreporting of police data amongst crashes minor injuries.

Secondly, while this study identified areas which may be amenable to safety audits, further analysis is required before specific interventions can be recommended. We estimated the latitudes and longitudes based on the street names, names of junctions, closest milepost and distance to the milepost and other landmarks provided in the police reports so these locations might not be perfectly accurate. On-site built environment inspection and analysis are warranted to verify the potential hazards and suggest specific interventions for these locations.

Conclusion

According to police data, in Galle, Sri Lanka most road traffic victims were male, between the ages of 21 and 50, and were motorcyclists or three-wheel drivers. While almost half of the crashes reported involved only minor injuries, over 16% of crashes involved grievous or fatal injuries. The Galle City center has numerous crash hot spots for injury for all types of road users. Further analysis at these locations is necessary to recommend specific interventions for each type of road user.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank our colleagues at the University of Ruhuna, the Deputy Inspector General of Police for the southern range of Sri Lanka and the Galle City and Port Police who without their support, hard work, persistence and cooperation this project would not have been completed.

Funding: Research support funding for this project was received from the Duke Global Health Institute and the Fudan University Center for Global Health. Dr. Staton would like to acknowledge salary support funding from the Fogarty International Center (Staton, K01 TW010000-01A1).

Contributor Information

Vijitha De Silva, Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka, Adjunct Professor, Duke Global Health Institute, Durham, USA, pvijithadesilva123@yahoo.com.

Hemajith Tharindra, Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka, tharindraavh@gmail.com.

Joao Ricardo Nickenig Vissoci, Faculty of Medicine, Faculdade de INGA, Maringa, Brazil, joaovissoci@gmail.com.

Luciano Andrade, State University of West of Parana / Unioeste. Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil. Public Health Research Group - Unioeste, Brazil. DGHI Global Injury Collaboration - Duke University, luc.and1973@gmail.com.

Badra Chandanie Mallawaarachchi, Southern Provincial Director of Health Services, Office, Galle, Sri Lanka, bhadrachandanie@gmail.com.

Truls Østbye, Duke Global Health Institute, Durham, North Carolina, truls.ostbye@duke.edu.

Catherine A. Staton, Division of Emergency Medicine, Duke University Medicine Center, Duke Global Health Institute, catherine.staton@duke.edu.

References

- Anselin L, Exploratory spatial data analysis in a geocomputational environment Geocomputation, a primer. Wiley, New York, 1998: p. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TC and Gatrell AC, Interactive spatial analysis. Essex: Longman, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara G, et al. SPRING and TerraLib: Integrating Spatial Analysis and GIS. in Proceedings of the SCISS Specialist Meeting New Tools for Spatial Data Analysis Santa Barbara, California, USA 2002. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade L, et al. , Brazilian Road Traffic Fatalities: A Spatial and Environmental Analysis. PLoS ONE, 2014. 9(1): p. e87244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Census and Statistics of Sri Lanka. 2013.

- Dharmarathne SD, Jayatilleke AU, and Jayatilleke AC, 70-year trends of road traffic crashes, injuries, and fatalities in Sri Lanka: a systematic analysis. Lancet, 2013. 381: p. 35–35. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, et al. , Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata- driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 2009. 42(2): p. 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopits E and Cropper M, Traffic Fatalities and economic growth. 2003, World Bank: Washington, D.C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project, [program]. 2014.

- Peden M, et al. , and (Eds), World report on road traffic injury prevention: summary. 2004, World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Peden M, McGee K, and K. E (Eds), Injury: A leading cause of the global burden of disease, 2000. 2002, World Health Organization: Geneva [Google Scholar]

- Periyasamy N, et al. , Under reporting of road traffic injuries in the district of Kandy, Sri Lanka. BMJ Open, 2013. 3(11): p. e003640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sri Lanka Police Statistics. 2010.

- Waller LA and Gotway CA, Spatial Clustering of Health Events: Regional Count Data. Applied Spatial Statistics for Public Health Data: p. 200–271. [Google Scholar]

- Weerawardena W, et al. , Analysis of patients admitted with history of road traffic accidents to surgical unit B Teaching Hospital Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Anuradhapura Medical Journal, 2013. 7(1): p. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2013). Global status report on road safety 2013: supporting a decade of action. 2013, World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]