Abstract

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is a satiety hormone that is highly expressed in brain regions like the hippocampus. CCK is integral for maintaining or enhancing memory, and thus may be a useful marker of cognitive and neural integrity in participants with normal cognition, mild cognitive mpairment (MCI), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). CSF CCK levels were examined in 287 subjects from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Linear or voxel-wise regression was used to examine associations between CCK, regional gray matter (GM), CSF AD biomarkers, and cognitive outcomes. Briefly, higher CCK was related to a decreased likelihood of having MCI or AD, better global and memory scores, and more GM volume primarily spanning posterior cingulate cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, and medial prefrontal cortex. CSF CCK was also strongly related to higher CSF total tau (R2=0.339) and p-tau181 (R2=0.240), but not Aβ1–42. Tau levels partially mediated CCK and cognition associations. In conclusion, CCK levels may reflect compensatory protection as AD pathology progresses.

Keywords: Cholecystokinin, Alzheimer’s Disease, Neuropathology, MRI, Biomarkers, Cognition

Introduction

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is a 33-amino acid satiety hormone secreted in the small intestines during digestion that binds to CCK-A receptors (CCKAR). CCK is secreted to allow the uptake of nutrients, most specifically fat uptake and metabolism of fatty acids (Pietrowsky, et al., 1994). CCK is stimulated by fat and protein ingestion to signal the pancreas to release pancreatic enzymes into the duodenum, as well as to signal the secretion of bile salts from the gall bladder into the duodenum. A main function of CCK is to slow gastric emptying to allow time for proper digestion. Patients with AD have shown changes in their eating behavior, including both increased and decreased food intake, suggesting instability in weight regulation. Patients also manifest changes in food variety preferences and their eating patterns (Morris, et al., 1989). Malnutrition is common and weight loss is seen in 40% of AD patients (Wallace, et al., 1995). Dietary changes, due to food preferences of patients with AD, tend to contain a higher proportion of carbohydrates and a reduced intake of proteins (Greenwood, et al., 2005). Hyperphagia is also found in a third of all AD patients (Morris, et al., 1989). The reason for hyperphagia is unknown, but there may be a link to decreased satiety hormones or decreased sensitivity to these hormones (Adebakin, et al., 2012). In concert, a decline in body mass index (BMI) is associated with an increased risk of developing AD (Buchman, et al., 2005). This change in body mass could be due to muscle wasting (i.e., sarcopenia) or a result of decreased food uptake.

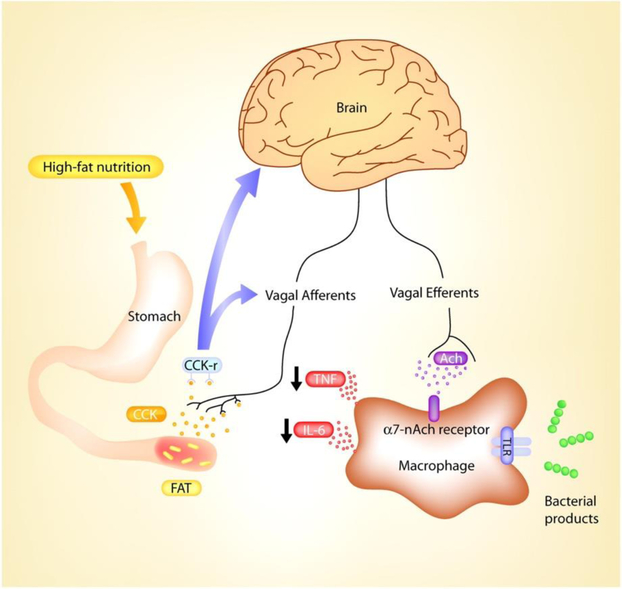

Interestingly, CCK receptors are found not only in the gut as CCK-A receptors, but also in the brain as CCK-B receptors (Pietrowsky, et al., 1994). Figure 1 illustrated the function of CCK peripherally as well as centrally. CCK is also the most abundant neuropeptide in the brain and selectively binds to CCK-B receptors, or CCKBR (Pietrowsky, et al., 1994). Indeed, CCK-B receptors are highly expressed in the hippocampus (Dockray, et al., 1978) (Innis, et al., 1979,Zarbin, et al., 1983), a brain region integral in memory formation that is adversely affected early in Alzheimer’s disease, or AD (Braak, et al., 1993). Hippocampal injection or cell culturing with CCK agonists or antagonists respectively improves or impairs long-term potentiation and memory in rodents by acting on CCKBR (Sebret, et al., 1999); (Wen, et al., 2014). Memory impairment in aged rodents also corresponds to less CCK expression (Croll, et al., 1999). Further, cerebral cortex has the highest concentration and CCK-specific binding in the brain (Saito, et al., 1980), where endogenous CCK activity may produce long-term potentiation in medial prefrontal cortex akin to hippocampus (Liu and Kato, 1996). Thus, it is important to observe if metabolic biomarkers related to body weight and dietary regulation dynamics are associated with neural, cognitive, and other behavioral outcomes relevant to AD.

Figure 1.

Bi-directional CCK pathways in the periphery and brain. This diagram is re-used with permission from the original publisher.

Despite a rich animal literature showing consistent enhancement or amelioration of memory by CCK-B activation, its role is virtually unknown in AD. AD-related changes in brain include progressive structural atrophy and decreased functional integrity (Klöppel, et al., 2018), leading to forgetfulness and progressively worsening memory loss (Azuma, et al., 2018). These changes occur in the presence of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) tangles, as observed in brain tissue at autopsy or antemortem through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). While CCK-B receptor binding does not differ in cognitively normal vs. AD patients (Löfberg, et al., 1996), regional differences in post-mortem CCK concentration suggest an AD-like pattern of decreased expression (Mazurek and Beal, 1991).

Thus, we examined if levels of CSF CCK were associated with onset and severity across the AD spectrum, and determined if CCK was related to AD-like changes in cognition, neuroimaging, and classic AD biomarkers like Aβ and tau.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Data from late middle-aged to aged adults were obtained from the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. For up-to-date information, see http://www.adni-info.org. Written informed consent was obtained from all ADNI participants at their respective ADNI sites. The ADNI protocol was approved by site-specific institutional review boards. All analyses used in this report only included baseline data, however measures were taken periodically for the database spanning a time of 90 months. Baseline CSF data for CCK was available for 287 subjects: 86 CN, 135 MCI, and 66 AD.

Participants with MCI had the following diagnostic criteria: 1) memory complaint identified by the participant or their study partner; 2) abnormal memory as assessed by the Logical Memory II subscale from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, with varying criteria based on years of education; 3) Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score between 24 and 30; 4) Clinical dementia rating of 0.5; 5) Deficits not severe enough for the participant to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease by the physician on site at screening. Participants with AD met similar criteria. However, they were required to have an MMSE score between 20 and 26, a clinical dementia rating of 0.5 or 1.0, and NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD.

Mass Spectrometry and Fasting Glucose

Data was downloaded from the Biomarkers Consortium CSF Proteomics MRM dataset. As described previously (Spellman, et al., 2015), the ADNI Biomarkers Consortium Project investigated the extent to which selected peptides, measured with mass spectrometry, could discriminate among disease states. Briefly, Multiple Reaction Monitoring-MS (MRMMS) was used for targeted quantitation of 567 peptides representing 221 proteins in a single run (Caprion Proteome Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada). Analyses for this report focused on CCK levels, which were assayed in the CSF proteomics panel, for which the peptide AHLGALLAR was chosen because it performed better in most analyses (data not shown).

Amyloid and Tau CSF Biomarkers

CSF sample collection, processing, and quality control of p-tau-181, total tau, and Aβ1–42 are described in the ADNI1 protocol manual (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/) and (Shaw, et al., 2011).

Apolipoprotein E ε4 genotype

The ADNI Biomarker Core at the University of Pennsylvania conducted APOE genotyping. We characterized participants as being “non-APOE4” (i.e., zero APOE ε4 alleles) or “APOE4” (i.e., one to two APOE ε4 alleles).

Neuropsychological Assessment

ADNI utilizes an extensive battery of assessments to examine cognitive functioning with particular emphasis on domains relevant to AD. A full description is available at http://www.adni-info.org/Scientists/CognitiveTesting.aspx. All subjects underwent clinical and neuropsychological assessment at the time of scan acquisition. Neuropsychological assessments included: The Clinical Dementia Rating sum of boxes (CDR-sob), Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE), Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), and AD Assessment Schedule - Cognition (ADAS-Cog). A composite memory score encompassing the RAVLT, ADAS-Cog, MMSE, and Logical Memory assessments was also utilized (Crane, et al., 2012). Additionally, a composite executive function score comprising Category Fluency—animals, Category Fluency—vegetables, Trails A and B, Digit span backwards, WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution, Number Cancellation and 5 Clock Drawing items was used (Gibbons, et al., 2012). These composite scores were used in formal analyses to represent global memory and executive function among subjects.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Acquisition and Pre-Processing

T1-weighted MRI scans were acquired within 10–14 days of the screening visit following a back-to-back 3D magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) scanning protocol described elsewhere (Jagust, et al., 2010). Images were pre-processed using techniques previously described (Willette, et al., 2013). Briefly, the SPM12 “New Segmentation” tool was used to extract modulated gray matter (GM) volume maps. Maps were smoothed with a 8mm Gaussian kernel and then used for voxel-wise analyses.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (FDG-PET)

FDG-PET acquisition and preprocessing details have been described previously (Jagust, et al., 2010). Briefly, 185 MBq of [18–153-F]-FDG was injected intravenously. After 30 minutes, six 5-minute frames were acquired. Frames of each baseline image series were coregistered to the first frame and combined into dynamic image sets. Each set was averaged, reoriented to a standard 160 × 160 × 96 voxel spatial matrix of resliced 1.5 mm3 voxels, normalized for intensity, and smoothed with an 8 mm FWHM kernel. In order to derive the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR), pixel intensity was normalized according to the pons since it demonstrates preserved glucose metabolism in AD (Dowling, et al., 2010). Normalization to the pons removed inter-individual tracer metabolism variability. The Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template space was used to spatially normalize images using SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/)). A subset of subjects underwent FDG-PET scans and analyses included in this report.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) or SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/). Binomial logistic regression was used to assess the odds ratio of a given participant being diagnosed as AD versus MCI or CN reference group. Linear mixed regression tested the main effect of CSF CCK on neuropsychological performance, modulated GM maps, FDG maps, and CSF biomarkers including Aβ1–42, total tau, and p-tau-181. Covariates included age at baseline and sex in all models. Years of education was also covaried when analyzing memory and cognitive performance. For voxel-wise analysis, 2nd-level linear mixed models tested the main effect of CCK on regional GM volume and FDG, controlling for age, sex, education, and baseline diagnosis. Based on the literature, contrasts tested if higher CCK was related to more regional GM or FDG. Statistical thresholds were set at p < .005 (uncorrected) and p < .05 (corrected) for voxels and clusters respectively. Results were considered significant at the cluster level. As described previously (Willette, et al., 2015), in order to reduce type 1 error, we utilized a GM threshold of 0.2 to ensure that voxels with <20% likelihood of being GM were not analyzed. For GM, Monte Carlo simulations in ClusterSim (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/doc/manual/3dClustSim) were used to estimate that 462 contiguous voxels were needed for such a cluster to occur at p < 0.05 family-wise error corrected. For FDG voxel-wise analyses, Monte Carlo simulations in ClusterSim were used to estimate that 224 contiguous voxels were needed for such a cluster to occur at p < 0.05 family-wise error corrected.

Results

Data Summary

Clinical, demographic, and CSF data for subjects with CSF CCK are presented in Table 1. Years of education, percent of APOE4 carriers, and age were not significantly different between participants diagnosed as CN, MCI or AD. As anticipated for this ADNI sub-population, cognitive function, observed utilizing global cognitive tests, was significantly different across CN, MCI, and AD groups (all p < 0.05). CSF CCK levels were significantly lower in AD (p<.001) versus participants with MCI or AD.

Table 1.

Demographic Data for Subjects with CSF CCK

| CN (N=86) | MCI (N=135) | AD (N=66) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75.70 ± 5.54 | 74.69 ± 7.35 | 74.98 ± 7.57 |

| Education (years) | 15.64 ± 2.97 | 16.00 ± 2.96 | 15.11 ± 2.96 |

| Sex (% Female) | 48.8% | 32.59% | 43.9% |

| APOE Status (% E4 carriers) | 24.4% | 52.6% | 71.2% |

| Cholecystokinin (ng/mL) | 13.48 ± 0.56 | 13.47 ± 0.53 | 13.23 ± 0.56 |

| CSF Total Tau (pg/mL) | 70.33 ± 27.64 | 102.99 ± 51.68 | 126.17 ± 60.69 |

| Ptau-181 (pg/mL) | 24.12 ± 11.97 | 35.25 ± 15.13 | 41.95 ± 20.60 |

| Abeta 1–42 (pg/mL) | 208.20 ± 56.05 | 161.21 ± 52.72 | 141.12 ± 37.39 |

| CDR-sob | 0.02 ± 0.11 | 1.56 ± 0.88 | 4.34 ± 1.56 |

| MMSE | 29.05 ± 1.02 | 26.91 ± 1.74 | 23.52 ± 1.85 |

| ADAS-COG11 | 6.05 ± 2.90 | 11.72 ± 4.33 | 18.88 ± 6.71 |

| Memory Factor (Z-score) | 0.98 ± 0.50 | −0.15 ± 0.57 | −0.90 ± 0.55 |

Values are mean ± SD. Chi-square analyses were conducted to examine differences between gender and APOE4 status. The ADNI memory factor values are Z-scored with mean 0 and a standard deviation of 1, based on 810 ADNI subjects with baseline memory data (Crane, et al., 2012). AD-Alzheimer’s disease; AD Assessment Schedule - Cognition (ADAS-Cog); Clinical Dementia Rating sum of boxes (CDR-sob); CN-cognitively normal; MCI-mild cognitive impairment; Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE).

Clinical Characteristics and AD Risk

Logistic regression was used to examine if higher CSF CCK expression predicted a decreased likelihood of being MCI or AD. The reference group was CN. The likelihood ratio statistic [X2=27.563, p<.001] indicated that higher CSF CCK levels predicted a lower Odds Ratio for being MCI or AD [Wald=13.437, β=−1.039, Exp(B)=0.354, p < 0.001]. These results suggest that a per ng/mL increase in CSF CCK corresponded to a roughly 65% less likelihood of being diagnosed with AD versus CN or MCI. Higher levels of CSF CCK were not related to increased risk when comparing CN vs. MCI, CN vs. AD, or MCI vs. AD individually. Among MCI participants, a per unit increase in CCK was related to a 61.7% less likelihood (Wald=6.708, p=.010) of progressing to AD (i.e., MCI-P) versus remaining stable with MCI (i.e., MCI-S).

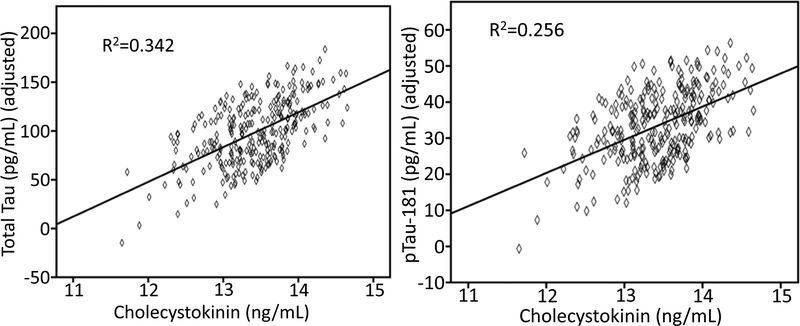

AD CSF Biomarkers

To examine the relationship between CSF CCK and AD CSF biomarkers Aβ1–42, ptau-181, and total tau regression model analyses were performed with age, sex, BMI, baseline diagnosis, APOE4 status as covariates. A significant association with Aβ1–42 was not observed. However, as seen in Figure 1, higher levels of CSF CCK were significantly associated with higher levels of CSF total tau (β±SE = 37.857±4.799, F=62.237, p< 0.001) and CSF ptau-181 (β±SE = 10.046±1.630, F=37.992, p< 0.001).

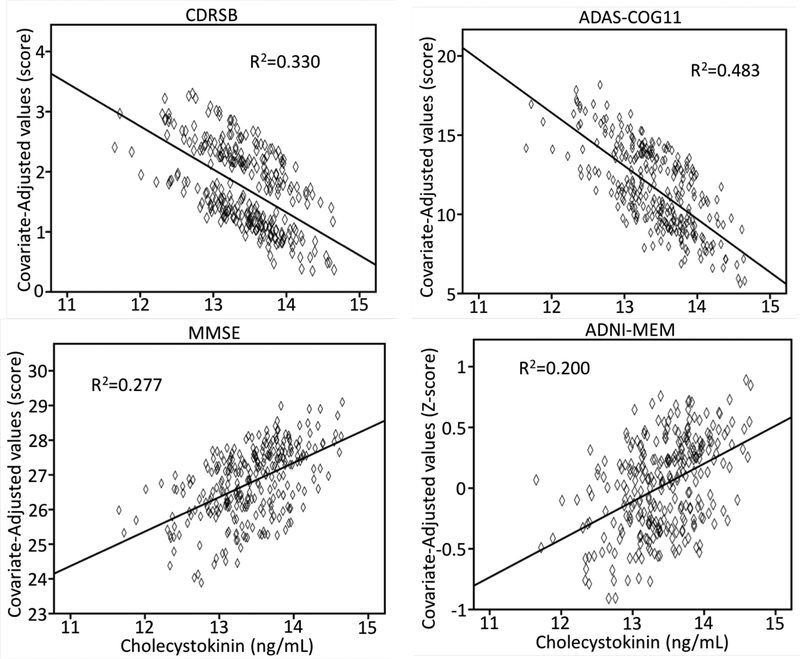

Global Cognition, Memory, and Executive Function

As illustrated in Figure 2, regression models showed that higher CSF CCK was related to better global cognition scores for CDR-sob, ADAS-cog11, and MMSE. Similarly, higher CCK was associated with better memory factor and executive function factor (β±SE=0.156±0.077, p<.05) scores.

Figure 2.

The association between higher CSF CCK and higher CSF total tau and ptau-181.

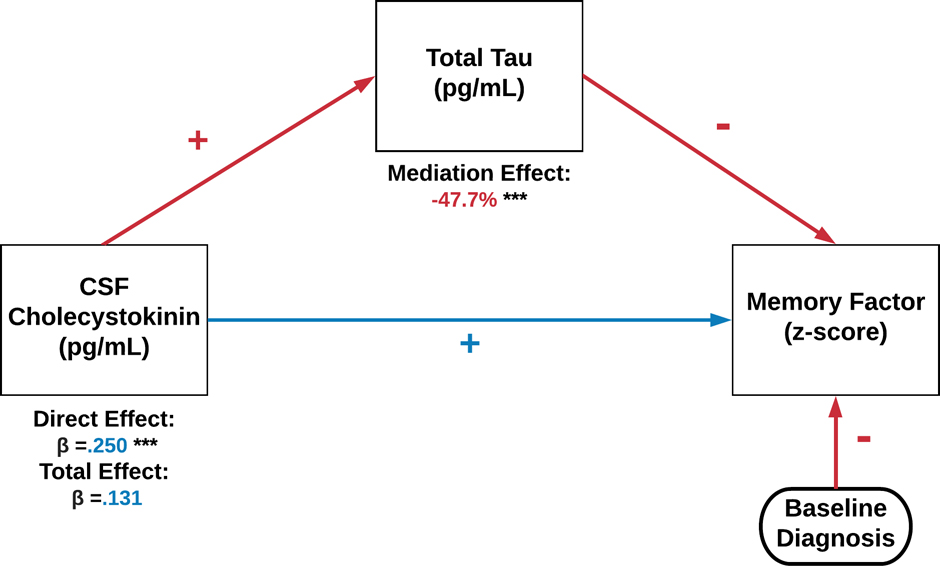

Preacher-Hayes Mediation of CCK and Cognition Outcomes

We also explored if CSF AD biomarkers modified associations between CCK and cognitive outcomes. For CDR-sob, no CSF markers mediated associations with CCK.

For ADAS-cog11 and CCK (direct effect β±SE= −3.110±0.585, p<.001), higher total tau acted as a partial mediator, reducing the influence of CCK by 24% (indirect effect β±SE=0.735±0.063, p<.05). For MMSE and CCK (direct effect β±SE=0.631±0.190, p<.001), ptau-181 acted as a partial mediator, reducing the influence of CCK by 26% (indirect effect β±SE= −0.164±0.095, p<.05).

For the memory factor and CCK, both total tau and p-tau181 acted as partial mediators. Specifically, as indicated in Figure 3, total tau reduced the influence of CCK on the memory factor by nearly half. In exploratory analyses, we examined if total tau mediation differed by baseline clinical diagnosis (CN, MCI, AD) or MCI conversion (MCI-S, MCI-P). CN and AD showed no mediation effect, whereas for MCI total tau continued to reduce the influence of CCK on the memory factor (direct effect β±SE=0.387±0.104, p<001) by 49.6% (indirect effect β±SE=−0.192±0.054). For MCI conversion, Supplemental Figure 1 illustrates that the direct effect of higher CCK on better memory scores MCI-S (β±SE=0.533±0.174, p=.003), which was reduced by 40.9% through total tau partial mediation (p<.001). By contrast, the direct effect for MCI-P was much weaker (β±SE=0.122) and rendered non-significant by full mediation of total tau (p<.001).

Figure 3.

The association between CSF CCK and cognitive scores, the Clinical Dementia Rating sum of boxes (CDR-sob), Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE), a composite memory score (ADNI-MEM), and AD Assessment Schedule - Cognition (ADAS-Cog).

In a separate model, p-tau181 reduced the influence of CCK on the memory factor (direct effect β±SE=0.186±0.064) by 36% (indirect effect β±SE=−0.067±.0263). No effects were significant when stratifying by baseline diagnosis or MCI conversion. Aβ1–42 was not a significant mediator for any cognitive measure.

Finally, for the executive function factor and CCK, both total tau and p-tau181 acted as partial mediators. Specifically, total tau reduced the influence of CCK on the memory factor (direct effect β±SE=0.355±0.087, p<.001) by 50% (indirect effect β±SE= −0.178±0.041, p<.001).

In a separate model, p-tau181 reduced the influence of CCK on the memory factor (direct effect β±SE=0.315±0.082, p<.001) by 47% (indirect effect β±SE= −0.148±0.036, p<.001). In exploratory analyses, no mediation analyses were significant when splitting by baseline clinical diagnosis or MCI conversion.

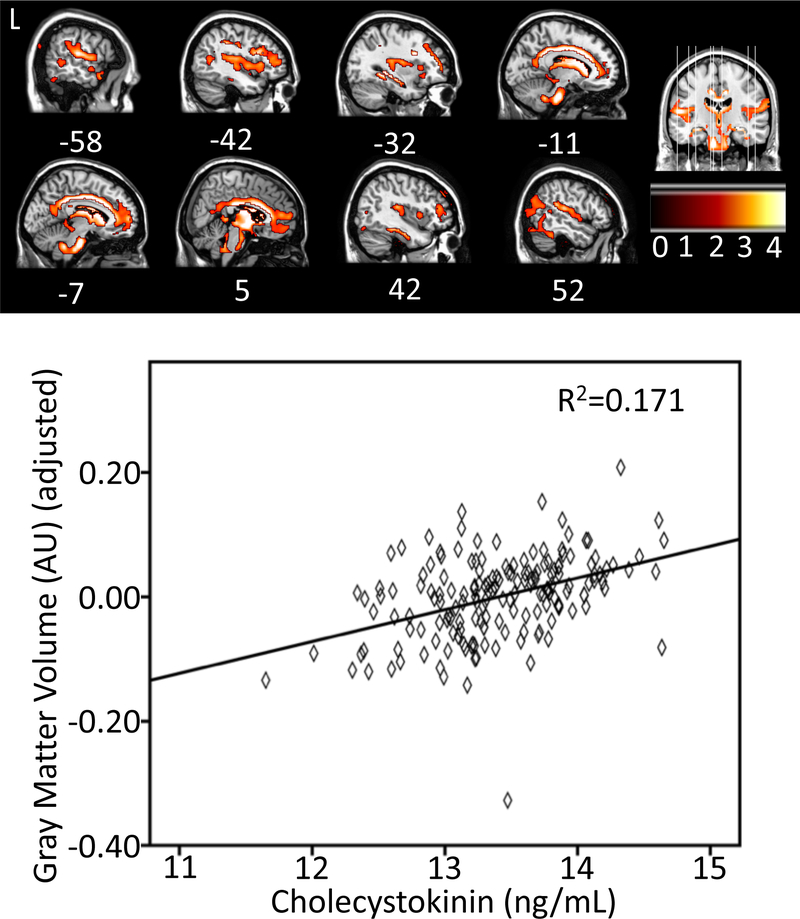

Regional Gray Matter Volume

To determine the relationship between CSF CCK and regional gray matter volume, a voxel-wise analysis was performed using SPM 12 among a subset of 303 participants. Higher CSF CCK was significantly associated with greater GM volume in a large cluster of voxels (k=11,962) primarily spanning cingulate cortex and parahippocampal gyrus, as well as thalamus, superior temporal sulcus, and medial prefrontal cortex (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 4.

Preacher-Hayes mediation of CSF CCK, total tau, and a composite memory score at baseline.

Regional 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography

Among 138 participants with FDG data, higher CSF CCK was not significantly associated with an increase in 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (FDG PET) glucose uptake.

Discussion

In this study, we hypothesized that CCK may serve as a useful metabolic biomarker for predicting AD outcomes, due to previous research looking at CCK-B and its role in maintaining or enhancing memory (Liu and Kato, 1996) (Sebret, et al., 1999) (Wen, et al., 2014). Although there was no statistically significant differences between groups when looking at Aβ, tau, or APOE4 carriers, clear trends were observed. We found that patients with AD had modestly lower CCK than CN or MCI. Per ng/mL increase in CCK, there was a roughly 65% decreased likelihood of having MCI or AD vs. CN and a 62% decreased likelihood of MCI progression from MCI to AD. These results suggest that higher CCK levels are related to better cognitive outcomes. Post-mortem tissue analysis has been mixed, with some groups noting no change (Perry, et al., 1981) (Ferrier, et al., 1983) or decreased expression (Mazurek and Beal, 1991). Per ng/mL increase in CCK, there was a roughly 65% decrease in likelihood of being diagnosed with MCI or AD. Similarly, Higher CCK was associated with better performance in memory, executive function, and global cognitive tests, which via mediation was partly mitigated by levels of CSF tau species but not Aβ1–42. CCK has consistently been implicated as a protective or enhancing factor for memory formation. For example, in a rodent study that included CCK knockout mice (CCK-KO), the mice without CCK performed worse on the Morris water-maze test compared to wild type mice while evincing similar locomotion and food intake, indicating that CCK was a factor in learning and memory (Lo, et al., 2008). CCK administration is directly able to induce or curb long-term potentiation (Sebret, et al., 1999) (Wen, et al., 2014), which is a well-established molecular process thought to underlie learning and memory.

We further observed that higher CSF CCK levels were also correlated with more regional GM volume in areas such as parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex, and superior and medial prefrontal gyri. The parahippocampal gyrus is part of the limbic system, which plays a crucial role in memory and is affected in AD with atrophy in GM (Köhler, et al., 1998). Atrophy in the hippocampus and posterior cingulate cortex strongly track disease progression and underlie memory decline (Pengas, et al., 2010). Medial prefrontal cortex is not only integral for memory retrieval, but also executive function as well (West, 1996). These results suggest that as CCK levels increase, cognitive functions such as memory may improve due to the protection of GM in memory-intensive regions of the brain.

In our study, we found no correlation between CSF CCK and Aβ, however, strong relationships were observed between higher CCK and higher tau levels. While no existing work ties CCK to amyloid or tau to our knowledge, other studies have tested the relationship between AD markers and other satiety hormones. In a study conducted by Guo et al. (2016), Aβ was added to PC12 cells to reaffirm the fact that Aβ causes apoptosis due to cytotoxicity. However, when leptin, a satiety hormone released from adipose tissue, was added to the PC12 cells along with the Aβ, significantly less cell death was observed. This protective phenomenon of leptin may be due to increased activation of JAK2, used in the regulation of the phosphorylation of the tau protein. When JAK2 was inhibited in the presence of Aβ, there was an increase in phosphorylated tau regardless of whether leptin was present. Similarly, with leptin administration, there was more JAK2 activation which caused decreased GSK-3 activation and less damage caused by the presence of Aβ (Guo, et al., 2016). GSK-3 is found in the brains of many patients with AD (Asuni, et al., 2006) and is involved with the hyper phosphorylation of the tau protein. Thus, CCK may serve as a protectant against AD by suppressing expression of GSK-3 and increasing JAK2 activation. With increased CCK levels in patients with more severe pathology, it may be possible that CCK is, acting in a similar way to leptin, trying to protect the brain from neuronal cell death, and not serving a pathogenic effect by directly increasing tau levels. At a certain point, GSK-3 levels may increase such that the compensatory function of CCK is overridden, leading to an increase in accumulation and phosphorylation of tau. Indeed, total tau and ptau-181 levels partly mediate CCK and cognitive scores and strongly decrease such associations. Furthermore, the association between higher CCK and better memory scores was seen in MCI-S but not MCI-P, due to full mediation by total tau. Therefore, CCK may not increase tau and ptau-181 levels per se, but act as a protective response to the neuronal damage that is tied to tau accumulation, which may be mitigated by progressive neurodegeneration.

Limitations of this study should be addressed. Using data from ADNI, we were unable to obtain dietary data, or other measures of body composition besides BMI. We were also unable to track changes in CCK over time as this was only measured at baseline. In conclusion, higher levels of CCK predicted better cognitive outcomes and more gray matter in memory-specific regions. Higher CCK was also related to more CSF total tau and ptau-181. CCK may act as a protectant against AD by activated JAK2, and thus reducing the GSK-3 activation. We propose that as AD progression occurs, CCK levels increase in efforts to protect against further damage potentially induced by tau. Additional research would need to be done to further examine the relationship between CCK and tau over time. CCK levels may be a useful marker of cognitive and volumetric loss due in part to increased accumulation of tau, which may be useful for AD prognosis or a potential target to maintain memory in the face of AD pathology.

In conclusion, CCK may be a useful biomarker for examining AD-related associations with gray matter atrophy, cognitive function, and especially tau deposition. CCK is not only an abundant neuropeptide, but is also released as a response to the ingestion of primarily fat and proteins. Thus, future work should examine if dietary changes might increase CCK expression in CSF, and if such changes are related to less AD-related pathology and cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5.

The association between more CSF CCK and more regional gray matter volume. The graph depicts the relationship at a sub maximum voxel in a sagittal cross section in mid cingulate gyrus at 10, −27, 38.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by the College of Human Sciences at Iowa State University, NIH grant AG047282, and the Alzheimer’s Association Research Grant to Promote Diversity grant AARGD-17–529552. No funding source had any involvement in the report. Data collection and sharing for this project were funded by the ADNI (National Institutes of Health Grant U01-AG-024904) and Department of Defense ADNI (award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the Alzheimer’s Association and the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private-sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuroimaging at the University of Southern California. The data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- Adebakin A, Bradley J, Gümüsgöz S, Waters EJ, Lawrence CB 2012. Impaired satiation and increased feeding behaviour in the triple-transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. PLoS One 7(10), e45179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asuni AA, Hooper C, Reynolds CH, Lovestone S, Anderton BH, Killick R 2006. GSK3alpha exhibits beta-catenin and tau directed kinase activities that are modulated by Wnt. Eur J Neurosci 24(12), 3387–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K, Toyama T, Katano M, Kajimoto K, Hayashi S, Suzuki A, Tsugane H, Iinuma M, Kubo KY 2018. Yokukansan Ameliorates Hippocampus-Dependent Learning Impairment in Senescence-Accelerated Mouse. Biol Pharm Bull 41(10), 1593–9. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b18-00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, Bohl J 1993. Staging of Alzheimer-related cortical destruction. Eur Neurol 33(6), 403–8. doi: 10.1159/000116984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Shah RC, Evans DA, Bennett DA 2005. Change in body mass index and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology 65(6), 892–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176061.33817.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, Carle A, Gibbons LE, Insel P, Mackin RS, Gross A, Jones RN, Mukherjee S, Curtis SM, Harvey D, Weiner M, Mungas D, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. 2012. Development and assessment of a composite score for memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Brain Imaging Behav 6(4), 502–16. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9186-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll SD, Chesnutt CR, Greene NA, Lindsay RM, Wiegand SJ 1999. Peptide immunoreactivity in aged rat cortex and hippocampus as a function of memory and BDNF infusion. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 64(3), 625–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockray GJ, Gregory RA, Hutchison JB, Harris JI, Runswick MJ 1978. Isolation, structure and biological activity of two cholecystokinin octapeptides from sheep brain. Nature 274(5672), 711–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling NM, Hermann B, La Rue A, Sager MA 2010. Latent structure and factorial invariance of a neuropsychological test battery for the study of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology 24(6), 742–56. doi: 10.1037/a0020176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier IN, Cross AJ, Johnson JA, Roberts GW, Crow TJ, Corsellis JA, Lee YC, O’Shaughnessy D, Adrian TE, McGregor GP 1983. Neuropeptides in Alzheimer type dementia. J Neurol Sci 62(1–3), 159–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons LE, Carle AC, Mackin RS, Harvey D, Mukherjee S, Insel P, Curtis SM, Mungas D, Crane PK 2012. A composite score for executive functioning, validated in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) participants with baseline mild cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav 6(4), 517–27. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9176-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood CE, Tam C, Chan M, Young KW, Binns MA, van Reekum R 2005. Behavioral disturbances, not cognitive deterioration, are associated with altered food selection in seniors with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60(4), 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Li D, Shen H, Jin B, Ren Y, Li M, Xing Y 2016. Leptin-Sensitive JAK2 Activation in the Regulation of Tau Phosphorylation in PC12 Cells. Neurosignals 24(1), 88–94. doi: 10.1159/000442615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis RB, Corrêa FM, Uhl GR, Schneider B, Snyder SH 1979. Cholecystokinin octapeptide-like immunoreactivity: histochemical localization in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76(1), 521–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Bandy D, Chen K, Foster NL, Landau SM, Mathis CA, Price JC, Reiman EM, Skovronsky D, Koeppe RA, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. 2010. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative positron emission tomography core. Alzheimers Dement 6(3), 221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klöppel S, Yang S, Kellner E, Reisert M, Heimbach B, Urbach H, Linn J, Weidauer S, Andres T, Bröse M, Lahr J, Lützen N, Meyer PT, Peter J, Abdulkadir A, Hellwig S, Egger K, Initiative A.s.D.N. 2018. Voxel-wise deviations from healthy aging for the detection of region-specific atrophy. Neuroimage Clin 20, 851–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler S, Black SE, Sinden M, Szekely C, Kidron D, Parker JL, Foster JK, Moscovitch M, Wincour G, Szalai JP, Bronskill MJ 1998. Memory impairments associated with hippocampal versus parahippocampal-gyrus atrophy: an MR volumetry study in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 36(9), 901–14. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(98)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JK, Kato T 1996. Simultaneous determination of cholecystokinin-like immunoreactivity and dopamine release after treatment with veratrine, NMDA, scopolamine and SCH23390 in rat medial frontal cortex: a brain microdialysis study. Brain Res 735(1), 30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CM, Samuelson LC, Chambers JB, King A, Heiman J, Jandacek RJ, Sakai RR, Benoit SC, Raybould HE, Woods SC, Tso P 2008. Characterization of mice lacking the gene for cholecystokinin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294(3), R803–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00682.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löfberg C, Harro J, Gottfries CG, Oreland L 1996. Cholecystokinin peptides and receptor binding in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 103(7), 851–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01273363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MF, Beal MF 1991. Cholecystokinin and somatostatin in Alzheimer’s disease postmortem cerebral cortex. Neurology 41(5), 716–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CH, Hope RA, Fairburn CG 1989. Eating Habits in Dementia: A Descriptive Study. British Journal of Psychiatry 154(6), 801–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengas G, Hodges JR, Watson P, Nestor PJ 2010. Focal posterior cingulate atrophy in incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 31(1), 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RH, Dockray GJ, Dimaline R, Perry EK, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE 1981. Neuropeptides in Alzheimer’s disease, depression and schizophrenia. A post mortem analysis of vasoactive intestinal peptide and cholecystokinin in cerebral cortex. J Neurol Sci 51(3), 465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrowsky R, Specht G, Fehm HL, Born J 1994. Comparison of satiating effects of ceruletide and food intake using behavioral and electrophysiological indicators of memory. Int J Psychophysiol 17(1), 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Sankaran H, Goldfine ID, Williams JA 1980. Cholecystokinin receptors in the brain: characterization and distribution. Science 208(4448), 1155–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebret A, Léna I, Crété D, Matsui T, Roques BP, Daugé V 1999. Rat hippocampal neurons are critically involved in physiological improvement of memory processes induced by cholecystokinin-B receptor stimulation. J Neurosci 19(16), 7230–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Figurski M, Coart E, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon AJ, Lewczuk P, Dean RA, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Initiative A.s.D.N. 2011. Qualification of the analytical and clinical performance of CSF biomarker analyses in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol 121(5), 597–609. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0808-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman DS, Wildsmith KR, Honigberg LA, Tuefferd M, Baker D, Raghavan N, Nairn AC, Croteau P, Schirm M, Allard R, Lamontagne J, Chelsky D, Hoffmann S, Potter WZ, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I., Foundation for, N.I.H.B.C.C.S.F.P.P.T. 2015. Development and evaluation of a multiplexed mass spectrometry based assay for measuring candidate peptide biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) CSF. Proteomics Clin Appl 9(7–8), 715–31. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JI, Schwartz RS, LaCroix AZ, Uhlmann RF, Pearlman RA 1995. Involuntary weight loss in older outpatients: incidence and clinical significance. J Am Geriatr Soc 43(4), 329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen D, Sun D, Zang G, Hao L, Liu X, Yu F, Ma C, Cong B 2014. Cholecystokinin octapeptide induces endogenous opioid-dependent anxiolytic effects in morphine-withdrawal rats. Neuroscience 277, 14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RL 1996. An application of prefrontal cortex function theory to cognitive aging. Psychological bulletin 120(2), 272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willette AA, Bendlin BB, Starks EJ, Birdsill AC, Johnson SC, Christian BT, Okonkwo OC, La Rue A, Hermann BP, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Sager MA, Asthana S 2015. Association of insulin resistance with cerebral glucose uptake in late middle-aged adults at risk for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 72(9), 1013–20. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willette AA, Xu G, Johnson SC, Birdsill AC, Jonaitis EM, Sager MA, Hermann BP, La Rue A, Asthana S, Bendlin BB 2013. Insulin Resistance, Brain Atrophy, and Cognitive Performance in Late Middle–Aged Adults. Diabetes Care 36(2), 443–9. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbin MA, Innis RB, Wamsley JK, Snyder SH, Kuhar MJ 1983. Autoradiographic localization of cholecystokinin receptors in rodent brain. J Neurosci 3(4), 877–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.