Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of death globally. In 2013, CVDs were responsible for approximately 17 million deaths worldwide (32%), with >75% occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 Hypertension is the leading remediable risk factor for CVD; it affects >1 billion people worldwide and is responsible for >10 million largely preventable deaths each year.1 Among all individuals with hypertension, 33% are not aware of their condition, and among those who are aware, only 56% are receiving treatment.2 Furthermore, only 28% of people with hypertension worldwide have their blood pressure controlled (ie, at a clinical target of <140/90 mm Hg).2

Prevention of CVD with population strategies such as salt reduction, smoking cessation and smoke-free policies, and laws to reduce air pollution are paramount.3 Alongside prevention efforts, there always will be a need to specifically address the treatment of hypertension. Improved diagnosis and treatment of hypertension is the most cost-effective means of improving premature mortality in LMICs.4 A major obstacle to hypertension control, however, is the absence of comprehensive primary healthcare services, including limited access to safe and effective medications and lack of systems to effectively deliver prevention, screening, and treatment. Building on lessons learned from the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and tuberculosis in LMICs, as well as successful models of hypertension control in the United States and Canada,5–9 the control of hypertension is attainable using a health system-strengthening approach.10 Furthermore, using hypertension as an entry point to strengthen health services establishes an improved healthcare infrastructure for comprehensive, sustainable management of all chronic conditions.

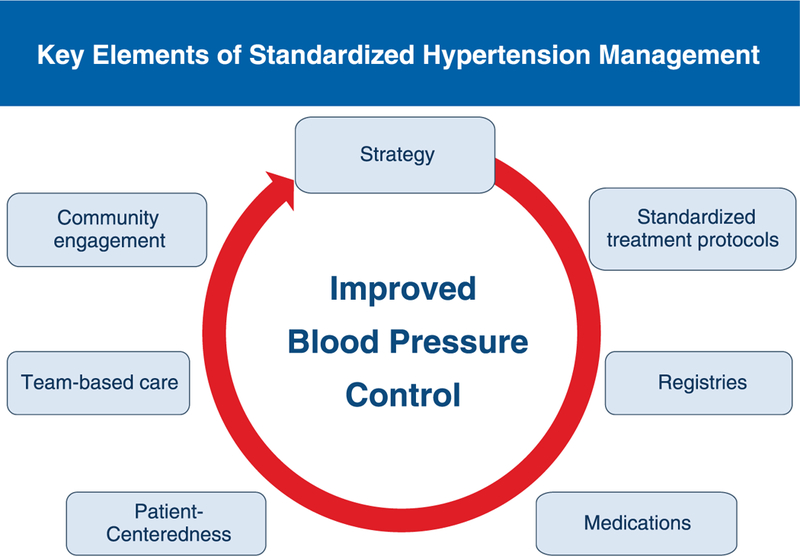

In this perspective, we describe an approach that was developed to improve blood pressure control and thus reduce related morbidity and mortality. The approach we encourage is called standardized hypertension management (Fig.), which involves using evidence-based clinical interventions to improve healthcare delivery. These interventions include the use of guidelines-based standardized treatment protocols; team-based care (task shifting and collaboration); patient empowerment; a core set of medications (formulary) along with improved procurement mechanisms to increase the availability and affordability of these medications; and registries for cohort monitoring and evaluation with specific metrics for quality improvement, performance assessment, and community engagement. With political will and strong partnerships, this approach provides the groundwork to reduce the burden of CVD. In addition, this approach will strengthen primary care delivery and can be applied to other chronic conditions for improved management of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) overall.

Fig.

Key elements of standardized hypertension management.

Implementation of the standardized hypertension management approach in the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) region, known as the Standardized Hypertension Treatment and Prevention Project (SHTP) began in 2013 in Barbados and has been described elsewhere.11 The Barbados pilot has been completed and similar efforts have been initiated in Chile, Colombia, and Cuba. This perspective provides an update on the progress of our efforts to prevent CVD and briefly describes the preliminary results from the Barbados pilot as well as other efforts in the region.

The SHTP, which uses standardized hypertension management and has all of the components recommended by the chronic care model,12 does not promote the control of hypertension through a vertical program but rather advocates using hypertension as an entry point for comprehensive CVD management. PAHO has made great strides to broaden access to care and availability of medications for NCDs using PAHO’s Strategic Fund (http://www.paho.org\strategicfund). The fund makes treatment feasible in this region, if countries choose to use the mechanism for medication procurement. Although the SHTP places significant emphasis on the management and control of hypertension, an area that has been neglected in many countries, its framework and principles fully support the prevention of CVD/NCDs, particularly through reducing salt consumption, promoting physical activity and a healthy diet, and reducing harmful use of alcohol and exposure to tobacco smoke/advocating for smoking cessation. These lifestyle changes are important in addressing many NCDs and the comorbidities commonly seen in patients with hypertension, such as diabetes mellitus.

The Caribbean region has led the way with the first SHTP pilot in Barbados and its promising results; 18 months post-implementation, >30,000 individuals were screened and the hypertension prevalence in the two pilot sites was 33%. Notably, there was an increase in blood pressure control rates, from 51% to 66%, during the 18 months of the program. This 15% increase in blood pressure control is attributed largely to improved prescribing practices, as outlined in the standardized treatment protocols that were adopted. Prescriptions of the suggested first-line medication, chlorthalidone, increased by 3.5%, which also translated to cost savings for the overall program. As a result, the Barbados Drug Formulary, which is a government-funded entity that manages drug procurement for the country, continues to improve availability of the core set of antihypertensive pharmacologic medications, particularly fixed-dose combination pills.

Improvements in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure rates were seen across all age groups, but they were particularly prominent among individuals older than 60 years. Among women, however, the most significant declines were seen in 50- to 69-year-olds, and among men, the most significant declines were seen among those 20 to 49 years of age and those older than 70 years. The program plans to explore how to improve the management of hypertension among middle-aged men, a prominent challenge also in the United States. More than one-third of Barbadians aged 25 to 70 years have hypertension; therefore, the lessons learned and positive outcomes of this project will be disseminated and plans for national expansion in Barbados are under way.13

The Healthy Caribbean Coalition was instrumental in the success of the Barbados pilot and further extended the principles of standardized hypertension management to five Caribbean countries in collaboration with the University of the West Indies. The SHTP has been a key feature in the Healthy Caribbean Coalition’s Direct Aid Program Part 2’s Blood Pressure Control through Community Action Project. One-day community-based hypertension screening and monitoring workshops were conducted in Dominica, Haiti, Jamaica, St Lucia, and St Vincent. SHTP principles and experiences were shared at these workshops and were well received; in particular, the SHTP’s standardized hypertension treatment protocol was appreciated and recognized as a useful tool.

Those individuals identified as having high blood pressure through the Blood Pressure Control through Community Action Project were referred to clinical centers that had been trained in providing care using the standardized hypertension management approach. Several other countries in the PAHO region, including Antigua, the Bahamas, Curacao, Ecuador, Jamaica, and St Lucia, have expressed interest in SHTP. Regional expansion also has been undertaken, as mentioned above. Chile, Colombia, and Cuba are implementing a comprehensive and innovative approach aligned with the PAHO NCD agenda to reduce CVD risk through hypertension control and secondary prevention. This approach, inspired by the standardized hypertension management approach, as well as lessons learned from the pilot in Barbados, uses the following interventions: introducing simple, standardized, evidence-based treatment algorithms; improving the availability and access to a core set of high-quality medications; and instituting a clinical registry for patient monitoring and for evaluating the performance of the healthcare organization. This approach complements and reinforces current efforts in CVD/ NCD prevention in these countries, but it concurrently emphasizes the comprehensive management of hypertension to improve care. Health systems strengthening is needed as evidenced by the low levels of blood pressure control and poor coverage of secondary prevention, both critical interventions to reduce premature mortality as a result of CVD, in the region.

The goal of the SHTP demonstration projects was to strengthen existing health systems such that other chronic diseases also can be addressed. Lessons learned from these countries suggest that to effectively reduce the burden of hypertension within a care delivery system, it is essential to have strong policies, political will, and effective partnerships. In this vein, the World Hypertension League advocates for strategic planning by national and regional organizations using hypertension as a focus and endorses the standardized hypertension management approach.14

Standardized hypertension management complements population approaches to primary prevention. In combination with salt-reduction strategies, improved blood pressure control may avert >10 million deaths and adverse events caused by CVD.15 Furthermore, the interventions supported by this approach are invaluable for a necessary paradigm shift to adapt health systems that have historically focused care on acute infectious illnesses for the practice of preventive medicine and for the long-term management of chronic diseases. As such, we believe that standardized hypertension management will enhance healthcare delivery to reduce CVD burden worldwide.

The SHTP pilots were undertaken as a proof of concept to evaluate the feasibility of implementing evidence-based clinical interventions at the primary healthcare level. The aim was to strengthen health systems and to improve the quality of care of NCDs, specifically CVD, using hypertension as an entry point, in LMICs. The results of the pilot sites were promising, with increases in blood pressure control rates, development of registries for improved care, and improved prescribing practices. Key elements of the standardized hypertension management approach, including the use of standardized treatment algorithms, improved access to medications, and improved clinical monitoring systems, have been included in a more comprehensive global initiative for CVD prevention and treatment. The Global HEARTS initiative to reduce heart attacks and strokes will support the implementation of the HEARTS technical package, a set of six technical and operational interventions to scale-up CVD management at the primary healthcare level. These include Healthy lifestyles counseling, Evidence-based treatment protocols, Access to essential medicines and technologies, Risk-based management, Team-based care and task sharing, and Systems for monitoring. The Global HEARTS Initiative is being led by the World Health Organization in collaboration with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, PAHO, the World Heart Federation, the World Stroke Organization, the International Society of Hypertension, the World Hypertension League, and other partners.16

Clinicians should consider adapting the entire or aspects of the standardized hypertension management approach, particularly evidence-based standardized treatment protocols and clinical monitoring systems, to improve the management of hypertension and other NCDs in their patient populations. Efforts in the PAHO region, including in the United States and Canada, have been successful and have proven the effectiveness of this approach. Furthermore, with the launch of the Global HEARTS initiative, these evidence-based interventions have support from the global public health community. Combined with population-level policies from reducing salt consumption and tobacco use, an appreciable decrease in morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular disease is inevitable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Standardized Hypertension Treatment and Prevention Network for their contributions to the development of this framework. The members include Alma Adler, World Heart Federation; Sonia Y. Angell, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Samira Asma, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Michele Bashin, Public Health Institute; Rafael Bengoa, Minister of Health, Basque Region; Ana Isabel Barrientos Castro, Sociedad Interamericana de Cardiología and Sociedad Centroamericana de Cardiología; Barbara Bowman, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Francis Burnett, Organization of Eastern Caribbean States; Jose Castro, Pan American Health Organization; Norman Campbell, World Hypertension League; Beatriz Marcet Champagne, InterAmerican Heart Foundation; Kenneth Connell, University of West Indies; Jose De Gracia, Martin Didier, Caribbean Cardiac Society; Donald DiPette, University of South Carolina; Maria Cristina Escobar, Chile Ministry of Health; Daniel Ferrante, Argentina Ministry of Health; Thomas Gaziano, Harvard School of Public Health; Marino Gonzalez, Universidad Simon Bolivar; Sir Trevor Hassell, Health Caribbean Coalition; Anselm Hennis, Pan American Health Organization; Rafael Hernandez, Universidad Centroccidental Lisandro Alvarado, Venezuela; Maryam Hinds, Barbados Drug Service; Marc Jaffe, Kaiser Permanente; Fernando Lanas, Universidad de La Frontera, Chile; Patricio Lopez-Jaramillo, Latin American Society of Hypertension; Fleetwood Loustalot, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Ben Lumley, Public Health England; Javier Maldonado, Colombia Ministry of Health; Thelma Nelson, National Health Fund; Jose Miguel do Nascimento Junior, Brazil Ministry of Health; Pedro Ordunez, Pan American Health Organization; Marcelo Orias, Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension; Jose Ortellado, Latin American Society of Internal Medicine; Pragna Patel, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Jacqueline Poselli, Venezuela Foro Farmaceutico de Las Américas; Agustin Ramirez, International Society of Hypertension; Lynn Silver, Public Health Institute; Donald Simeon, Caribbean Cardiac Society; Valerie Steinmetz, Public Health Institute; Kathryn Taubert; the Honorable Alvina Reynolds, St Lucia Ministry of Health; Hilary Wall, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Jamie Waterall, Public Health England; Fernando Wyss, Interamerican Society of Cardiology; Amy Valderrama, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Jose Fernando Valderrama, Colombia Ministry of Health; and Fernando Lanas Zanetti, Interamerican Society of Cardiology.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Pan American Health Organization.

The authors did not report any financial relationships or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators, Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks and clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:2287–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic review of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation 2016;134:441–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.First Global Ministerial Conference on Healthy Lifestyles and Noncommunicable Disease Control Prevention and control of NCDSL: priorities for investment. Moscow, 28–29 April 2011 http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/who_bestbuys_to_prevent_ncds.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nugent R Benefits and costs of the non-communicable disease targets for the post-2015 development agenda. http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/sites/default/files/pp_nugent_-health_ncd.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed December 28, 2017.

- 5.Jaffe MG, Lee GA, Young JD, et al. Improved blood pressure control associated with a large-scale hypertension program. JAMA 2013;310:699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAlister FA, Wilkins K, Jofres M, et al. Changes in the rates of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Canada over the past two decades. CMAJ 2011;183:1007–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harries AD, Zachariah R, Jahn A, et al. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in Malawi—implications for managing other chronic diseases in resource-limited countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;52(Suppl 1): S14–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seita A, Harries AD. All we need to know in public health we can learn from tuberculosis care: lessons for non-communicable disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:429–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frieden TR, Berwick DM. The “Million Hearts” initiative—preventing heart attacks and strokes. N Engl J Med 2011;365:e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jafar TH, Hatcher J, Poulter N, et al. Community-based interventions to promote blood pressure control in a developing country: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel P, Ordunez P, DiPette D, et al. Improved blood pressure control to reduce cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: the Standardized Hypertension Treatment and Prevention Project. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2016;18:1284–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:64–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PAHO TV Standardized hypertension treatment project in Barbados. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bQ7j4g5qZVs. Accessed January 3, 2018.

- 14.Campbell NR, Lackland DT, Lisheng L, et al. The World Hypertension League challenges hypertension and cardiovascular organizations to develop strategic plans for the prevention and control of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2015;17:325–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angell SY, De Cock KM, Frieden TR. A public health approach to global management of hypertension. Lancet 2015;385:825–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Global Hearts Initiative. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/global-hearts/en. Accessed November 28, 2016.