Azithromycin (AZM) has been recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics for the treatment of shigellosis in children. In this study, 502 Shigella species isolated between 2004 and 2014 were tested for AZM epidemiological cutoff values (ECV) by disk diffusion.

KEYWORDS: azithromycin, epidemiological cutoff values, Shigella

ABSTRACT

Azithromycin (AZM) has been recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics for the treatment of shigellosis in children. In this study, 502 Shigella species isolated between 2004 and 2014 were tested for AZM epidemiological cutoff values (ECV) by disk diffusion. AZM MICs and the presence of the macrolide resistance genes [erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), ere(A), ere(B), mph(A), mph(B), mph(D), mef(A), and msr(A)] were determined for all 56 (11.1%) isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm. The distribution of AZM ECV MICs was also determined for 186 Shigella isolates with a disk zone diameter of ≥16 mm. Finally, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed on 15 Shigella flexneri isolates with an AZM disk zone diameter of <16 mm from different years and geographic locations. Serotyping the 502 Shigella species isolates revealed that 373 (74%) were S. sonnei, 119 (24%) were S. flexneri, and 10 (2%) were S. boydii. Of the 119 Shigella flexneri isolates, 48 (42%) isolates had an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm and a MIC of ≥16 µg/ml. With the exception of one isolate, all were positive for the macrolide resistance gene mph(A). S. flexneri PFGE showed four distinct patterns, with patterns I and II presenting with 92.3% genetic similarity. On the other hand, 2 (0.5%) of the 373 S. sonnei isolates had the AZM non-wild-type (NWT) ECV phenotype (those with acquired or mutational resistance), as the AZM MICs were ≥32 µg/ml and the isolates were positive for the mph(A) gene. Overall, our S. flexneri results are in concordance with the CLSI AZM ECV, but isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter between 14 and 15 mm should be carefully evaluated, as the S. flexneri AZM MIC for NWT isolates may need adjustment to 32 µg/ml. Our data on S. sonnei support that the AZM NWT ECV should be 11 mm for the disk diffusion zone diameter and ≥32 µg/ml for the MICs.

INTRODUCTION

Individuals suffering from shigellosis usually recover without antibiotic treatment, but some patients might need antibiotic intervention to reduce the duration and severity of the illness and to decrease the spread of the infection (1). In children with severe shigellosis symptoms, such as bloody diarrhea and fever, physicians usually start antimicrobial therapy (2, 3).

Shigellosis therapy may be either parenteral or oral, depending on the age of the patient.

Recently, Shigella isolates have been reported to be resistant to the common orally given antibiotics, such as ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, fluoroquinolones, and even the macrolides (4–6). The oral fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin can achieve high concentrations in the serum and stool and have activity against Shigella isolates. Yet ciprofloxacin prescription is avoided in children (1, 7).

The macrolide azithromycin (AZM) is widely used in children and is recommended as an alternative therapy for the treatment of shigellosis in adults infected with multidrug-resistant isolates (8). In the past few years, there has been a growing interest in azithromycin as the drug of choice for the treatment of most shigellosis cases. Azithromycin was found to have in vitro activity against most Shigella species, in addition to high intracellular concentrations (8). It has been recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics for treatment of shigellosis in children and by the World Health Organization as a second-line treatment in adults. However, recent reports have suggested that there are Shigella isolates that are not susceptible to azithromycin (4, 9, 10).

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) has not yet established guidelines for interpreting the antimicrobial sensitivity testing (AST) of azithromycin for Shigella isolates as susceptible or nonsusceptible. In 2018, the azithromycin disk diffusion epidemiological cutoff values (ECV) and interpretations were proposed by the CLSI only for S. flexneri (11). In this report, we utilized the S. flexneri disk diffusion ECV interpretation to evaluate the azithromycin ECV of Shigella isolates that had been isolated at Caritas Baby Hospital in Palestine between the years 2004 and 2014 and determined the molecular mechanism for azithromycin resistance (11).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical consideration.

The research conducted in this study was approved by the Caritas Medial Research Committee under approval number MRC-0035.

Study population.

Clinical strains of Shigella isolates (n = 502) were isolated from stool samples of pediatric patients presenting with diarrhea and seen at Caritas Baby Hospital, Bethlehem, between the years 2004 and 2014. The distribution of the Shigella isolates per year were as follows: 2004, 6; 2005, 85; 2006, 131; 2007, 93; 2008, 26; 2009, 31; 2010, 67; 2011, 25; 2012, 17; 2013, 12; and 2014, 9. The age of the patients ranged between 1 month and 14 years, with males constituting 54% of the patient population. The patients were mainly from the southern districts of Palestine, Bethlehem and Hebron.

Shigella species identification.

Patients’ stool specimens were inoculated on 5% sheep blood, MacConkey, xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD), and campylobacter agar plates in addition to selenite broth (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom). Inoculated plates were then incubated for 24 h at 35°C. Suspected Shigella colonies were identified according to colony morphology on XLD and MacConkey agars, the oxidase test, and biochemical analysis (triple sugar iron [TSI], sulfide indole motility [SIM], Simmon's citrate, mannitol, and urea) (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom). Identification of Shigella isolates was confirmed by serotyping the isolate using specific Shigella antisera (Denka Seiken Co., Tokyo, Japan). Samples with unclear biochemical or morphological results were confirmed using the API 20E test (bioMérieux, France) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Antibiotic sensitivity testing (AST).

The Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion ECV assay for 15-µg azithromycin (AZM) disks (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) was performed on and interpreted for all 502 Shigella isolates according to CLSI interpretation guidelines for S. flexneri (11). The ECV is a measurement that separates the bacterial population into wild-type (WT) bacteria and those with acquired or mutational resistance to azithromycin (non-wild type [NWT]). For S. flexneri only, the isolate was considered WT if the azithromycin zone diameter was ≥16 mm and NWT if the zone diameter was ≤15 mm.

On the other hand, based on the CLSI MICs (MICs) determined by broth microdilution, the ECV for S. flexneri and S. sonnei were WT if the MICs were ≤8 and ≤16 µg/ml, respectively, and NWT if the MICs were ≥16 and ≥32 µg/ml, respectively. In this study, the AZM ECV MIC using the Etest (bioMérieux, France) was determined for all Shigella isolates (n = 56) with a zone diameter of ≤16 mm (11). In addition, the AZM ECV MIC was determined for 186 (37.1%) randomly chosen Shigella species isolates with an AZM zone diameter of ≥16 mm.

Molecular detection of azithromycin resistance genes in Shigella species.

Total nucleic acid was extracted from fresh well-isolated colonies of all Shigella isolates whose AZM ECV were NWT (n = 56) by using a High Pure nucleic acid extraction kit (Roche, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Briefly, total nucleic acid was extracted from 200 µl of a no. 2 MacFarland bacterial suspension (6 × 108 CFU/ml) prepared in saline solution. Extracted DNA was eluted in 100 µl elution buffer and stored at −20°C pending molecular analysis.

Azithromycin-nonsusceptible isolates were screened for macrolide resistance by amplifying the erm genes [erm(A), erm(B), erm(C)], esterase genes [ere(A), ere(B)], phosphotransferase genes [mph(A), mph(B), mph(D)], and genes for acquisition of efflux pumps [mef(A), msr(A)] by PCR (12, 13). In addition, during the validation of the macrolide PCR assays, the amplified PCR products were sequenced using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Life Technologies, USA) on an ABI Prism sequencer 3130xl/genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) to confirm the identity of the amplified PCR product.

PFGE of S. flexneri isolates.

Subtyping of bacterial strains using the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) method was performed on 15 S. flexneri isolates to determine if there was a single clone of S. flexneri with an azithromycin NWT ECV phenotype spreading in the country. The isolates were taken from the years 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2014 and were chosen from different geographic areas. PFGE was performed according to the standardized and internationally validated PulseNet PFGE protocol employed by PulseNet laboratories of the U.S. CDC for Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella.

Genomic DNA from the 15 Shigella isolates was digested with NotI as a primary restriction enzyme and XbaI as a secondary enzyme (New England Biolabs) and separated in 1% SeaKem gold agarose gel, with a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF-DRIII system; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) under the following electrophoresis conditions: initial switch time, 5 s; final switch time, 35 s; voltage, 6 V/cm; included angle for the CHEF DRIII system, 120°; total running time, 18.5 h. XbaI-digested Salmonella serotype Braenderup strain H9812 was used as the molecular weight standard.

The gel was stained for 25 min with GelRed nucleic acid stain (Biotium Inc., Hayward, CA). The gel was then visualized with a Bio-Rad gel documentation system (Bio-Rad; Molecular Imager Gel Doc XR imaging system). Digital images were stored electronically as TIFF files, and the resulting TIFF images were analyzed using the BioNumerics version 5.10 software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium).

The PFGE band patterns were compared based on the Dice coefficient, and a dendrogram with a setting of 1.5% position tolerance for band comparison was constructed by a UPGMA (unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages) algorithm. Band similarity was determined according to the criteria suggested by Tenover et al. (14).

RESULTS

Shigella species serotyping and azithromycin NWT ECV.

Serotyping the 502 Shigella isolates revealed that 373 (74%) were S. sonnei, 119 (24%) were S. flexneri, and 10 (2%) were S. boydii. Of the 502 isolates, 56 (11.1%) of the isolates produced an azithromycin disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm. The majority of the Shigella isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm were S. flexneri 48 (86%). The numbers of S. sonnei and S. boydii isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm were 8 and 0, respectively.

Comparison of disk diffusion and MIC results for determining azithromycin NWT ECV in Shigella species.

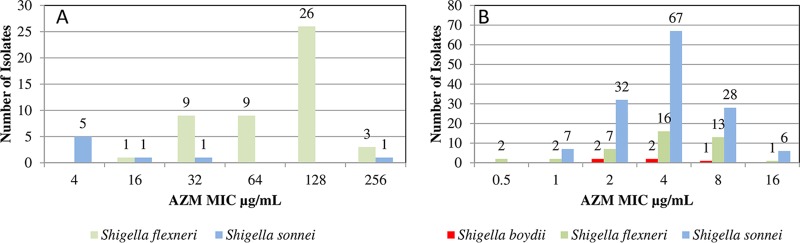

Shigella species (n = 56) with AZM NWT ECV according to the CLSI interpretation guidelines for S. flexneri and 186 randomly selected Shigella isolates with a disk diffusion zone diameter of ≥16 mm were tested to determine the AZM MICs (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG 1.

(A) Distribution of azithromycin MICs for Shigella species with azithromycin disk diffusion diameters of ≤15 mm. (B) Distribution of azithromycin MICs for Shigella species with azithromycin disk diffusion diameters of ≥16 mm.

Stratifying the Shigella by species revealed that all 48 S. flexneri isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm had an AZM MIC of ≥16 µg/ml (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, of the 8 S. sonnei isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm, 2 (25%) had an AZM MIC of ≥32 µg/ml (Fig. 1A). The 6 S. sonnei isolates with an AZM MIC of ≤32 µg/ml had an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter between 13 and 15 mm. None of the 10 S. boydii isolates had an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm.

All 186 Shigella isolates (140 S. sonnei [75.3%], 41 S. flexneri [22%], and 5 S. boydii [2.7%] isolates) with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≥16 mm had an AZM MIC of ≤16 µg/ml (Fig. 1B). AZM MICs between 0.5 and 4 µg/ml were noted in 136 (73%) of the Shigella isolates, of which 6 (4.3%) of the S. sonnei isolates exhibited an AZM MIC of 16 µg/ml.

Only one S. flexneri (2.4%) isolate demonstrated an AZM MIC of 16 µg/ml, indicating that it has the AZM NWT ECV based on CLSI guidelines (11).

Determination of azithromycin resistance mechanism.

All Shigella isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm (n = 56) were tested for all the different macrolide resistance mechanisms by PCR. Of the 56 isolates tested for erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), ere(A), ere(B), mph(A), mph(B), mph(D), mef(A), and msr(A), 49 isolates demonstrated a positive signal for mph(A) only. Of the 48 S. flexneri isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤15 mm, 47 gave a positive signal for the mph(A) gene, while 1 S. flexneri isolate with an AZM disk diffusion diameter of 14 mm gave a negative amplification for all of the macrolide resistance genes tested. Interestingly, this isolate demonstrated an AZM MIC of 16 µg/ml. Two S. sonnei isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤11 mm gave a positive amplification for the mph(A) gene, while all S. sonnei isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter between 12 and 15 mm gave a negative amplification for any of the genes (Table 1). S. flexneri AZM NWT ECV was detected mainly during the years 2005 (3 isolates; 6.3%), 2006 (36 isolates; 74.5%), 2007 (8 isolates; 17%), and 2014 (1 isolate; 2.1%).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of Shigella species azithromycin resistance patterns by disk diffusion, MICs, and presence of macrolide resistance genes

| AZM disk diffusion zone diameter (mm) | Total no. of isolates | Overall range of AZM MICs (µg/ml) |

S. flexneri |

S. sonnei |

S. boydii |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of isolates | MIC (µg/ml) | mph(A) | No. of isolates | MIC (µg/ml) | mph(A) | No. of isolates | MIC (µg/ml) | mph(A) | |||

| 6 | 28 | 64–256 | 27 | 64–256 | Positive | 1 | 256 | Positive | 0 | ||

| 7 | 9 | 64–256 | 9 | 64–256 | Positive | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 8 | 3 | 32–256 | 3 | 32–256 | Positive | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 9 | 1 | 32 | 1 | 32 | Positive | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 10 | 3 | 32–64 | 3 | 32–64 | Positive | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 11 | 3 | 32 | 2 | 32 | Positive | 1 | 32 | Positive | 0 | ||

| 12 | 1 | 32 | 1 | 32 | Positive | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 13 | 2 | 4–32 | 1 | 32 | Positive | 1 | 4 | Negative | 0 | ||

| 14 | 4 | 4–16 | 1 | 16 | Negative | 3 | 4–16 | Negative | 0 | ||

| 15 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | Negative | 0 | ||||

| Total ≤15 | 56 | 4–256 | 48 | 16–256 | 47/48 | 8 | 4–256 | 2/5 | 0 | ||

| ≥16 | 186 | 0.38–16 | 41 | 0.38–16 | NDa | 140 | 0.75–16 | NDb | 5 | ND | NDc |

ND, not determined. For S. flexneri isolates with an azithromycin disk diffusion zone diameter of ≥16 mm, all 6 tested for macrolide resistance genes were negative by PCR.

For S. sonnei isolates with an azithromycin disk diffusion zone diameter of ≥16 mm, all 15 tested for macrolide resistance genes were negative by PCR.

For S. boydii isolates with an azithromycin disk diffusion zone diameter of ≥16 mm, all 10 tested for macrolide resistance genes were negative by PCR.

Determination of clonal variation of the S. flexneri azithromycin-resistant isolates.

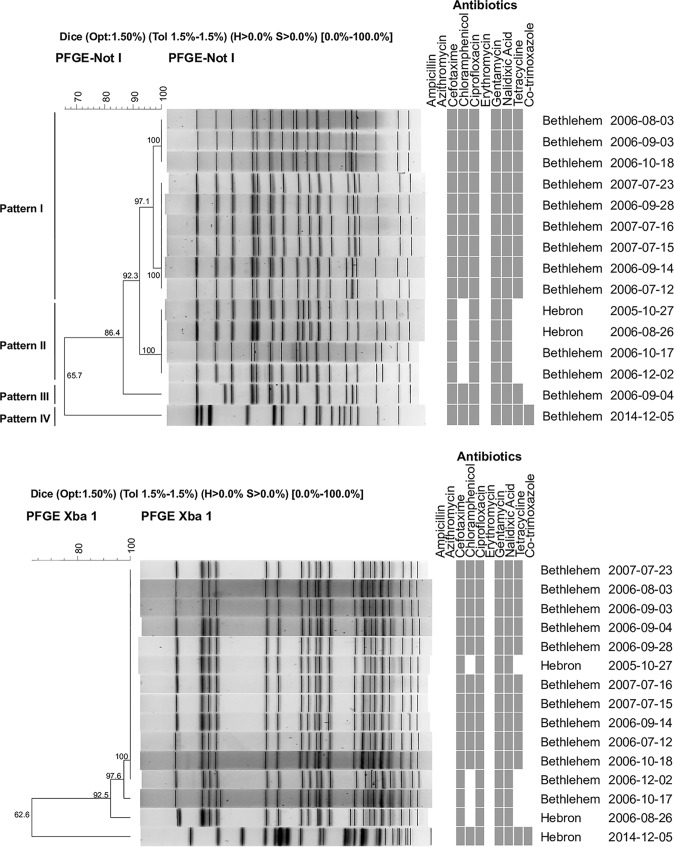

The genetic relatedness of S. flexneri isolates with the AZM NWT ECV phenotype was determined by PFGE using representative isolates from different years of the study. Genomic DNA of 15 S. flexneri isolates with an azithromycin NWT ECV phenotype from different isolation years, i.e., 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2014, were digested with two restriction enzymes, NotI as a primary restriction enzyme and XbaI as a secondary enzyme. NotI digestion yielded 16 to 18 DNA fragments, while those digested with XbaI yielded 20 to 23 DNA fragments (Fig. 2A and B). Based on NotI digestion, the 15 S. flexneri isolates were distributed into four PFGE groups arbitrarily designated patterns I, II, III, and IV. Two of these patterns (I and II), representing 13 isolates from the years 2005 to 2007, were more closely related to each other than the other patterns, with a similarity value of 92.3%. The third pattern (III), representing one isolate from the year 2006, appeared different from patterns I and II, with 86.4% similarity. The fourth pattern (IV), which comprised an isolate from the year 2014, was uniquely different from the rest, with a distinct NotI/XbaI PFGE pattern (Fig. 2A and B).

FIG 2.

(A) PFGE of Shigella flexneri NotI-digested chromosomal DNA along with antibiotic antimicrobial sensitivity testing patterns. In the columns headed “Antibiotics,” a gray box indicates a sensitive profile, and the absence of a gray box (white) indicates a resistant profile. The values on the tree represent the percent similarities between the isolates. (B) PFGE of Shigella flexneri XbaI-digested chromosomal DNA along with antibiotic antimicrobial sensitivity testing patterns. In the columns headed “Antibiotics,” a gray box indicates a sensitive profile, and the absence of a gray box (white) indicates a resistant profile. The values on the tree represent the percent similarities between the isolates.

Furthermore, the four proposed PFGE patterns after NotI digestion produced pattern-related antibiograms, of which PFGE pattern II appears to be the most antibiotic resistant (Fig. 2). XbaI Shigella genomic digestion did not separate the Shigella flexneri isolates into clear patterns that would relate to the isolate antibiograms.

According to criteria for interpreting PFGE patterns, and based on the PFGE patterns with NotI and XbaI digests, around 93.0% of the isolates recovered during 2006 and 2007 from an outbreak or sporadic cases were either indistinguishable or closely related strains.

DISCUSSION

Patients with shigellosis can present with severe clinical symptoms mandating antimicrobial therapy. In Palestine, Shigella isolate resistance patterns to oral antibiotics is very high. Data from 502 Shigella isolates collected from patients at Caritas Baby Hospital between 2004 and 2014 showed high resistance patterns to ampicillin (40.4%), cotrimoxazole (91.4%), and tetracycline (78.3%) (unpublished data). On the other hand, the NWT ECV for AZM was 11.1%. These oral antibiotic resistance patterns are similar to those from previous reports from Israel, Egypt, and the United States (15–17).

For the proper management of patients’ shigellosis infections, determining the Shigella isolates is of importance, as the resistance patterns between the different Shigella isolates differ dramatically. In our study, S. flexneri showed a high resistance pattern to the oral antibiotics ampicillin (85%), cotrimoxazole (78%), and tetracycline (50%) (unpublished data), as well as an NWT ECV for azithromycin (42%).

CLSI introduced the ECV to determine if S. flexneri and S. sonnei have or do not have phenotypically detectable resistance to azithromycin. Based on the testing methods employed and CLSI interpretive criteria, 48 of 119 (40%) of the S. flexneri isolates and 2 of 373 (0.5%) of a selected group of S. sonnei isolates were identified as NWT. Of these, 49 (98%) carried the plasmid-mediated mph(A) macrolide resistance mechanism. The mph(A) molecular mechanism of AZM resistance in Shigella species was similar to that reported in the United States and South Asia (5, 18, 19). Shigella species have been reported to acquire the macrolide mph(A) resistance mechanism from E. coli by plasmid transfer (12). No other macrolide resistance mechanisms were detected in the Shigella isolates in this study, including erm(B), which was detected in an earlier report from South Asia in some S. sonnei isolates (19).

All NWT ECV S. flexneri isolates that gave a positive amplification for one of the macrolide resistance genes also produced an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≤13 mm and an AZM MIC between 32 and 256 µg/ml. One isolate gave an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of 14 mm and an AZM MIC of 16 µg/ml but was negative for any macrolide resistance gene tested. Overall, our S. flexneri results are in concordance with the CLSI AZM ECV, but careful evaluation of isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter between 14 and 15 mm should be given (Table 1). This study also suggests that further investigations are needed to evaluate S. flexneri AZM MIC interpretation guidelines for NWT isolates (≥16 µg/ml) after careful evaluation of the clinical response of the patients to AZM treatment. In this study, two S. flexneri isolates had an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of 14 mm, were negative for all the macrolide resistance genes tested, and gave an AZM MIC of 16 mg/liter, while another S. flexneri isolate had an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of ≥16 mm and an AZM MIC of 16 mg/liter. This is discrepant with a report by Darton et al., which showed two S. flexneri isolates with an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter of 12 mm and an AZM MIC of 16 mg/liter and that were positive for either erm(B) or mph(A) (19).

Our S. sonnei data also support the possibility that the AZM NWT ECV could be introduced at ≤11 mm for disk diffusion and that the AZM NWT MIC could be kept at ≥32 µg/ml, as recommended by the CLSI (Table 1). Five isolates gave an AZM disk diffusion zone diameter between 13 and 15 mm and a MIC of 4, with the exception of one isolate, which had an AZM disk diffusion diameter of 14 mm and a MIC of 16 µg/ml. Similar observations of an AZM ECV were previously made for an S. sonnei isolate from South Asia (19). A possible explanation that this study did not address with regard to the reduced susceptibility of S. sonnei to AZM was the possible role of rplD, rplV, and 23S rRNA genes.

PFGE analysis of S. flexneri isolates with an AZM NWT ECV across the study period indicated that there was genetic similarity between the isolates that spread in the years 2005 to 2007. A genetic similarity value of 92.3% could indicate that there was a clonal spread of S. flexneri in the community. However, S. flexneri pattern I and II isolates were replaced by a those of a third pattern (III) in 2006 with 86.4% similarity to patterns I and II. All three patterns were replaced by a fourth pattern (IV) in 2014 that was uniquely different from patterns I, II, and III.

Utilization of oral antibiotics to treat Shigella isolates continues to be a challenge, as drug-resistant Shigella isolates continue to emerge. Laboratories should exert utmost readiness to meet the challenges of determining the sensitivity patterns of AZM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jain SK, Gupta A, Glanz B, Dick J, Siberry GK. 2005. Antimicrobial-resistant Shigella sonnei: limited antimicrobial treatment options for children and challenges of interpreting in vitro azithromycin susceptibility. Pediatr Infect Dis J 24:494–497. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000164707.13624.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil K, Khan SR, Mazhar K, Kaijser B, Lindblom GB. 1998. Occurrence and susceptibility to antibiotics of Shigella species in stools of hospitalized children with bloody diarrhea in Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 58:800–803. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morales Espinosa RM, González-Valencia G, Muñoz O, Torres J. 1993. Production of cytotoxins and enterotoxins by strains of Shigella and Salmonella isolated from children with bloody diarrhea. Arch Med Res 24:13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heiman KE, Karlsson M, Grass J, Howie B, Kirkcaldy RD, Mahon B, Brooks JT, Bowen A, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. Notes from the field: Shigella with decreased susceptibility to azithromycin among men who have sex with men–United States, 2002-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:132–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heiman KE, Grass JE, Sjolund-Karlsson M, Bowen A. 2014. Shigellosis with decreased susceptibility to azithromycin. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33:1204–1205. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan WA, Seas C, Dhar U, Salam MA, Bennish ML. 1997. Treatment of shigellosis. V. Comparison of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 126:697–703. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-9-199705010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamanna, Ramana J. 2016. Structural insights into the fluoroquinolone resistance mechanism of Shigella flexneri DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Microb Drug Resist 22:404–411. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2015.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boumghar-Bourtchai L, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Bingen E, Filliol I, Dhalluin A, Ifrane SA, Weill FX, Leclercq R. 2008. Macrolide-resistant Shigella sonnei. Emerg Infect Dis 14:1297–1299. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.080147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen GP, Harris KA. 2017. In vitro resistance selection in Shigella flexneri by azithromycin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00086-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00086-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassing RJ, Melles DC, Goessens WH, Rijnders BJ. 2014. Case of Shigella flexneri infection with treatment failure due to azithromycin resistance in an HIV-positive patient. Infection 42:789–790. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0594-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CLSI. 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (M100). CLSI, Wayne, PA.

- 12.Nguyen MCP, Woerther P-L, Bouvet M, Andremont A, Leclercq R, Canu A. 2009. Escherichia coli as reservoir for macrolide resistance genes. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1648. doi: 10.3201/eid1510.090696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojo KK, Ulep C, Van Kirk N, Luis H, Bernardo M, Leitao J, Roberts MC. 2004. The mef(A) gene predominates among seven macrolide resistance genes identified in gram-negative strains representing 13 genera, isolated from healthy Portuguese children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:3451–3456. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3451-3456.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol 33:2233–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Putnam SD, Riddle MS, Wierzba TF, Pittner BT, Elyazeed RA, El-Gendy A, Rao MR, Clemens JD, Frenck RW. 2004. Antimicrobial susceptibility trends among Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. isolated from rural Egyptian paediatric populations with diarrhoea between 1995 and 2000. Clin Microbiol Infect 10:804–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peleg I, Givon-Lavi N, Leibovitz E, Broides A. 2014. Epidemiological trends and patterns of antimicrobial resistance of Shigella spp. isolated from stool cultures in two different populations in Southern Israel. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 78:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erdman SM, Buckner EE, Hindler JF. 2008. Options for treating resistant Shigella species infections in children. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 13:29–43. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-13.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjolund Karlsson M, Bowen A, Reporter R, Folster JP, Grass JE, Howie RL, Taylor J, Whichard JM. 2013. Outbreak of infections caused by Shigella sonnei with reduced susceptibility to azithromycin in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1559–1560. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02360-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darton TC, Tuyen HT, The HC, Newton PN, Dance DAB, Phetsouvanh R, Davong V, Campbell JI, Hoang NVM, Thwaites GE, Parry CM, Thanh DP, Baker S. 2018. Azithromycin resistance in Shigella spp. in Southeast Asia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e01748-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01748-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]