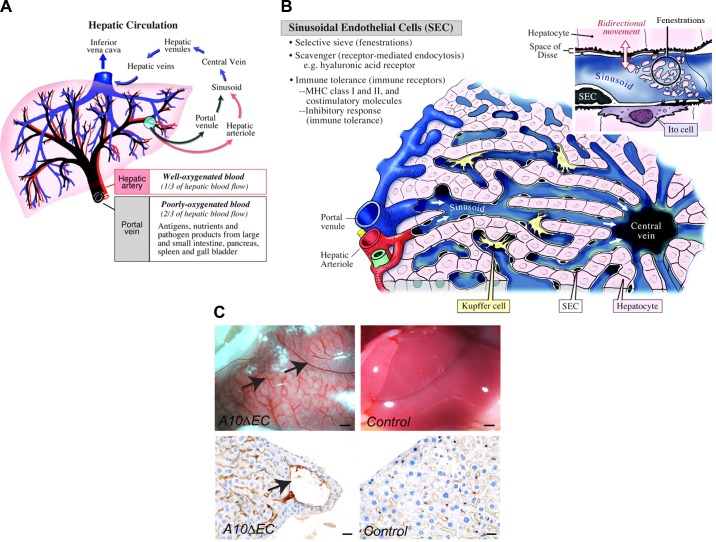

FIGURE 13.

Liver vasculature. A: major blood conduits through the liver are the portal vein, which carries poorly oxygenated but nutrient-rich blood from the gastrointestinal tract to the liver, and the hepatic artery, which delivers well-oxygenated blood to the liver. Input from both vascular beds flows through the sinusoids and drains into the central vein, which feeds hepatic venules, then into larger hepatic veins that drain into the inferior vena cava. B: the building blocks of liver lobules include input from the portal venule and hepatic arteriole, which feed into the sinusoids separately, but merge toward the center, where blood from the sinusoidal vasculature collects into the central vein. Adjacent hepatocytes process the nutrients and lipids in portal vein blood to generate bile. The sinusoidal endothelium functions as a selective sieve and scavenger, together with luminal monocyte-derived Kupffer cells, and as a mediator of immune tolerance. Inset: the sinusoidal vasculature contains large fenestrations (100–200 nm), also called sinusoidal openings, to allow transport of solutes and macromolecules as well as lipids to the hepatocytes for further processing. C: A10ΔEC mice have enlarged vessels on their liver surface that often end blindly under the liver surface, without connection to similarly large-caliber vessels for drainage (82). Histochemical analysis showed enlarged subcapsular vessels surrounded by thin-walled endothelial cells lacking evident mural cell coverage. [A and B are from Aird (4), with permission from Circ Res; C is from Glomski et al. (82), with permission from Blood.]