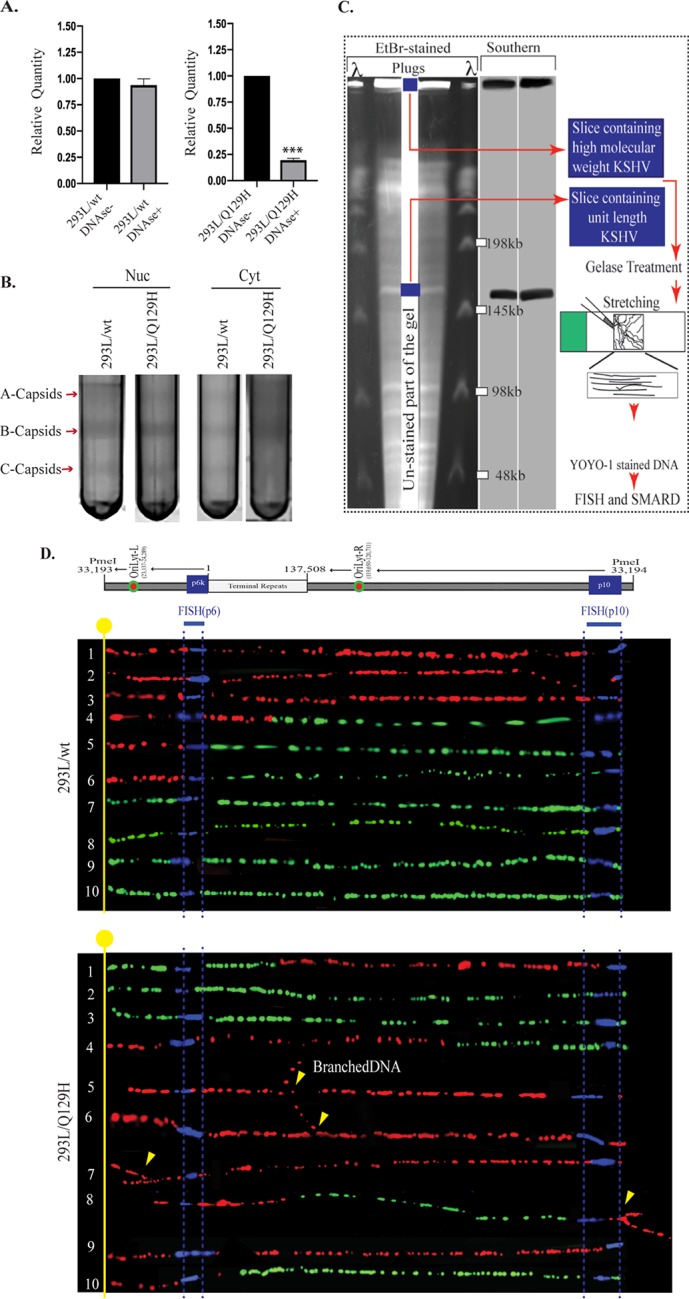

FIG 3.

ORF37’s DNase activity is required for efficient packaging of viral DNA and nuclear egress. (A) qPCR analysis of BamHI-digested total and encapsidated (DNase I-resistant) DNAs from 72-hpi 293L/wt and 293L/Q129H cells. When normalized to the total viral DNA, DNA encapsidation in 293L/Q129H cells was significantly reduced compared to the wt control; ***, P < 0.001. (B) Analysis of the KSHV capsids in 72-hpi 293L/wt and 293L/Q129H nuclear and cytoplasmic cell fractions purified by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation indicated larger amounts of A/B/C capsids for BAC16-wt than for the Q129H mutant (more A/B capsids and fewer C capsids) in the nuclear fraction; however, only B capsids could be seen in the 293L/Q129H cytoplasmic fractions compared to the wt control. The arrows indicate capsid bands designated A, B, and C. (C) Schematic illustrating the SMARD approach, including PFGE of PmeI-digested agarose plugs containing the dually labeled KSHV genome. The middle portion of the gel was stored to extract DNA, and the sides were used for EtBr staining and Southern blotting to localize the KSHV genome. The gel slices containing high-molecular-weight DNA were treated with gelase to isolate the DNA. Stretched DNA was subjected to FISH and SMARD analysis. (D) Microscopy image showing replicating BAC16-wt DNA and Q129H branched DNA. The KSHV genome was detected by FISH probe signals (blue). The first and second labels were detected by immunostaining and are shown in red and green, respectively. Branching of the DNA molecules is indicated by the yellow arrows. The transition site from red to green indicates the location of a replication fork.