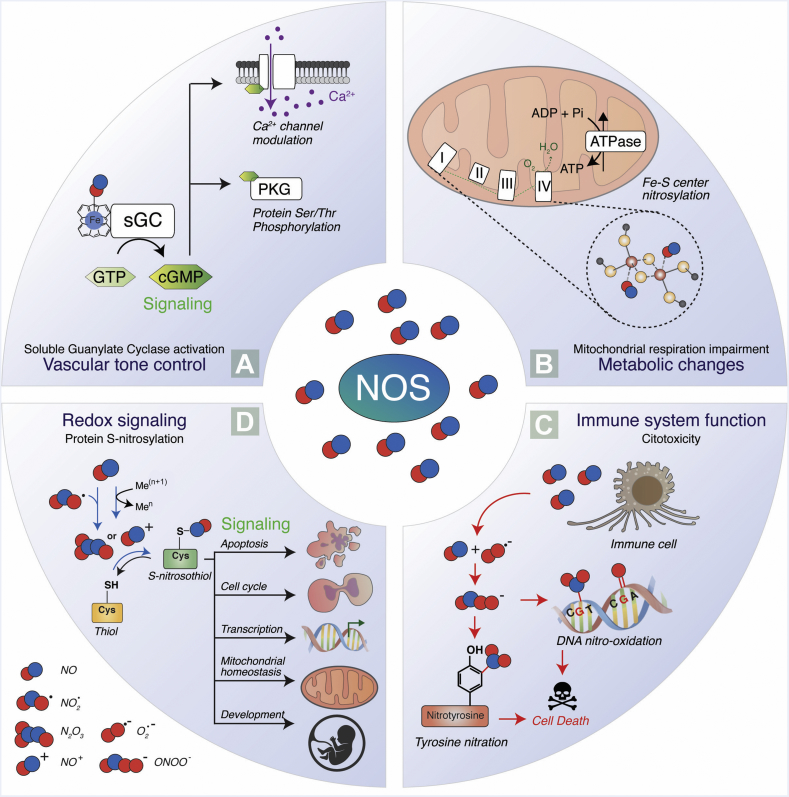

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of NO-mediated signaling pathways. (A) NO induces the soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) by binding its heme-group and stimulates the production of cyclic GMP (cGMP) [182]. cGMP production modulates calcium channels and activates the protein kinase G (PKG), leading to a downstream phosphorylation cascade that is important in muscle tone control. (B) Other central sensors of NO fluxes are mitochondria, which adjust the oxygen consumption rate and energy production according to NO levels. NO can affect the mitochondrial respiration rate by direct attachment to Fe-S centers or by the covalent binding to specific tyrosines (C) and cysteines (D) [[183], [184], [185]]. (C) Large amounts of NO produced by immune cells (e.g. macrophages) react with superoxide (O2·), generating the highly reactive peroxynitrite (ONOO-), which leads to protein tyrosine nitration, DNA nitro-oxidation, cell damage, and death. (D) The reaction between NO and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) or redox metals (e.g., Fe3+, Cu2+) generates dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3) or nitrosonium ion (NO+), respectively. Both these species can bind directly to cysteine residues (-SH) of proteins, forming S-nitrosothiols (-SNO). The reaction, termed S-nitrosylation, acts as a posttranslational modification that affects protein function, stability, localization and signaling. The processes in which protein S-nitrosylation plays a role include apoptosis, cell cycle, cell proliferation, gene transcription, mitochondrial homeostasis, and development [82,186,187].