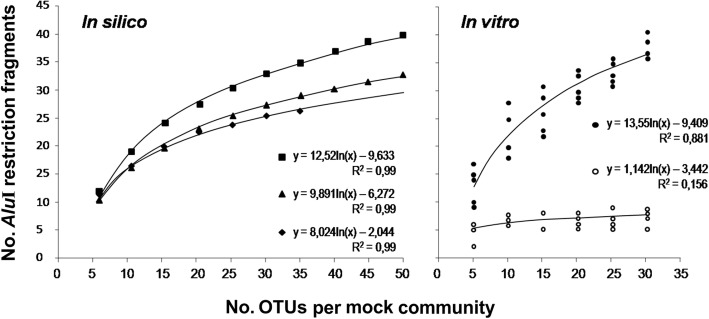

Fig. 4.

Theoretical and actual AluI restriction fragments of mock bacterial communities (MBCs). For all cases, the MBCs were assembled with 5-OTUs’ increments, according to the graphs. For both in silico and in vitro analyses, restriction fragments equal to, or less than 5-bp difference were considered as a single band and counted only once per MBC (see Methods). In silico analysis: the number of AluI fragments was defined from 16S rDNA sequences from various endophytic bacteria from database, followed by computational processing and restriction analysis by free online software (see Methods). ‘■’: sequences (OTUs) from the literature (Additional file 2: Table S2); ‘▲’: sequences from rice, Oryza sativa [54]; ‘♦’: sequences from bean, Phaseolus vulgaris [55]. The plotted data were the averages of maximum numbers of restriction fragments from 3000 random MBCs for the Additional file 2: Table S2’, rice’s and beans’ OTUs. In vitro analysis: the AluI fragments of 16S rDNA amplified by 799F/U1492R were obtained in two ways: ‘●’: pre MBC assembly ‘theoretical’ data; DNA extracted from cacao bacterial isolates (Additional file 1: Table S1) were individually subjected to PCR / AluI digestion (Fig. 2), computing the number of fragments per isolate prior to defining the MBCs; for each no. of OTUs on the horizontal axis, the total number of fragments for each of the 5 MBCs (Additional file 3: Table S3) were plotted. ‘○’: post MBC assembly ‘actual’ data; restriction fragments were obtained from PCR and digestion of previously pooled equimolar amounts of isolate DNAs, according to the no. of OTUs per MBC (Fig. 3). These experiments were repeated at least twice for all isolates and their MBCs. The respective regressions, equations and coefficients of determination are indicated in the graphs