Abstract

BACKGROUND

A majority of patients with insular tumors present with seizures. Although a number of studies have shown that greater extent of resection improves overall patient survival, few studies have documented postoperative seizure control after insular tumor resection.

OBJECTIVE

To (1) characterize seizure control rates in patients undergoing insular tumor resection, (2) identify predictors of seizure control, and (3) evaluate the association between seizure recurrence and tumor progression.

METHODS

The study population included adults who had undergone resection of insular gliomas between 1997 and 2015 at our institution. Preoperative seizure characteristics, tumor characteristics, surgical factors, and postoperative seizure outcomes were reviewed.

RESULTS

One-hundred nine patients with sufficient clinical data were included in the study. At 1 yr after surgery, 74 patients (68%) were seizure free. At final follow-up, 42 patients (39%) were seizure free. Median time to seizure recurrence was 46 mo (95% confidence interval 31-65 mo). Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that greater extent of resection (hazard ratio = 0.2899 [0.1129, 0.7973], P = .0127) was a significant predictor of seizure freedom. Of patients who had seizure recurrence and tumor progression, seizure usually recurred within 3 mo prior to tumor progression. Repeat resection offered additional seizure control, as 8 of the 22 patients with recurrent seizures became seizure free after reoperation.

CONCLUSION

Maximizing the extent of resection in insular gliomas portends greater seizure freedom after surgery. Seizure recurrence is associated with tumor progression, and repeat operation can provide additional seizure control.

Keywords: Insula, Glioma, Epilepsy, Extent of resection, Surgical outcome, Seizure outcome

ABBREVIATIONS

- AEDs

antiepileptic drugs

- CI

confidence interval

- EOR

extent of resection

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery

- IDH

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- WHO

World Health Organization

Gliomas arising from the insular region appear to be epileptogenic and may be secondary to the disruption of multiple connections.1-3 Management of insular gliomas remains a challenge given the insula's complex anatomy, proximity to significant vascular structures, and relationship to multiple functionally eloquent areas.1,4-7 Although several studies have reported the extent of resection of insular gliomas improving rates of overall and progression-free survival,8-16 few studies have measured rates of seizure freedom after insular glioma surgery.14,17-19 Of the few reported studies on seizure outcome, all focused on low-grade insular gliomas with relatively short-term follow-up.14,17,19 Additionally, there is no consensus regarding how the extent of insular glioma resection influences seizure outcome.

Contemporary intraoperative neuroimaging modalities and advances in cortical and subcortical mapping techniques have made it possible to perform greater extent of resection with a relatively low morbidity profile.12,20-23 With these advances in surgical resection and oncologic treatment, patients with gliomas are experiencing longer median overall and progression-free survival.9,12,16,24,25 Seizures in glioma patients pose a significant reduction in the quality of life metrics and are associated with varying degrees of cognitive impairments.26 Therefore, it is important to understand the impact of surgery on seizure outcomes in patients undergoing insular glioma resection and identify factors to optimize seizure control.

Using a cohort of patients who underwent insular glioma resection at our institution, we aim to (1) characterize seizure-control rates in patients undergoing insular tumor resection, (2) identify predictors of seizure control, and (3) evaluate the connection between seizure recurrence and tumor progression.

METHODS

Patient Selection

Between June 1997 and June 2015, 284 adults (>17 yr of age) underwent surgery at our institution for treatment of their insular glioma. All gliomas were evaluated by neuropathology at our institution, and tumors were considered insular location if the mass was located predominately within the insular lobe according to the prior-published reports.12,22 Medical records of the study population were retrospectively reviewed and patients were screened for history of seizure and related symptoms on initial presentation. Of those presenting with seizures, patients were excluded from the study for the following: prior resection at another institution (excluding those who only had prior biopsies), insufficient preoperative and postoperative seizure documentation, and those with <6 mo follow-up. The numbers of patients excluded from the study based on these criteria are summarized in Figure 1. A comparison between the baseline characteristics of the included and excluded patients is shown in Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1.

FIGURE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Flow chart demonstrating number of patients included and excluded according to study criteria.

A subset of the patients analyzed in the current study was included in a previously published study in which perioperative patient parameters including zone classification based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, clinical presentation, handedness, age at diagnosis, and immediate postoperative MRI characteristics, and histopathology review based on World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines were prospectively collected.27 All patients were consented. The study protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Research at our institution as a retrospective review study, and therefore, no additional patient consent is required prior to data collection.

Perioperative Data Collection

Records pertaining to patient demographics, seizure characteristics, and MRI findings were reviewed. Preoperative seizure data included the date of seizure onset, type of seizure (focal, focal with dyscognitive features, and generalized), presence and type of auras, and use and number of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Seizures control with the use of AEDs was defined as the complete absence of seizures after initiation of AEDs prior to surgery. Those who continued to have seizures despite being on AED are designated as having medically refractory seizures.

Tumor location was classified according to the Berger–Sanai Insular Glioma Classification System.12 The insula was divided into 4 zones by the sylvian fissure in the horizontal plane and foramen of Monro in the vertical plane. Using this method, classification for insular gliomas location included the following: zones I, II, III, IV, I + II, I + IV, II + III, III + IV, and all zones. Volumetric measures of pre- and postoperative imaging were performed as previously described.27 For each case, the tumor was segmented manually across all slices with region-of-interest analysis to compute volume in cubic centimeters. For all tumor grades, tumor volume was defined by the area of fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensity. Other imaging characteristics including FLAIR hyperintensity, hemorrhage, and enhancement patterns were described.

Operative data including the use of cortical and subcortical motor stimulation mapping, language mapping, and performance of awake surgery were recorded. During awake stimulation mapping, electrocorticography (ECoG) is routinely used to monitor after discharge potentials. Gross-total resection of the tumor was attempted, but subtotal resection was performed when involving eloquent brain regions as verified by intraoperative stimulation mapping. Extent of resection (EOR) was calculated as follows: [(preoperative tumor volume – postoperative tumor volume)/preoperative tumor volume × 100]. Classical tumor histopathology was determined according to the 2007 WHO brain tumor classification. After 2010, tumor molecular markers and genetic characterizations were more routinely performed. Commonly tested tumor markers included isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1)-R132 gene mutation, chromosome 1p/19q co-deletion, tumor protein (p53) gene mutation, X-linked alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome gene loss, epidermal growth factor receptor gene amplification, and phosphatase and tensin homolog gene deletion. Classification using the WHO 2016 Central Nervous System (CNS) tumor classification scheme based on integrated phenotypic and genotypic information was performed.28

Patient Outcome Measurements

All information pertaining to seizure control was documented in routine clinical visits and reviewed. Patients were assessed for seizure control using the Engel Classification of Seizures (Class I, seizure free or only auras; Class II, rare seizures; Class III, meaningful seizure improvement; and Class IV, no seizure improvement or worsening).29 Patients with Class I seizure status were further stratified: Class IA, completely seizure free; Class IB, nondisabling simple partial seizures; Class IC, some disabling seizures, but free of disabling seizures for at least 2 yr; and Class ID, generalized convulsions with AED discontinuation only.17 Postoperative AED use at last follow-up time point was recorded. In general, patients were continued on their preoperative AED after surgery for seizure prophylaxis. AEDs are weaned at the discretion of patient's primary care physician, neurologist, or neuro-oncologist. The primary outcome measures were seizure status after first resection at 1 yr and at last follow-up. For those who had repeat resections due to tumor progression and/or seizure recurrence, seizure status prior to repeat surgery was used as primary outcome measure. Secondary measures included seizure outcome after repeat resection and tumor progression, which is defined as evidence of WHO grade II or III tumor to higher grade lesions on either imaging or histopathology. Time to seizure recurrence and time to tumor progression were documented for each patient. Morbidity was defined as persistent dysfunction, defined as any motor, sensory, or language deficits 90 d after surgical intervention.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables and summarized as median for continuous variables after assessing for normal distribution and frequency of distribution for categorical variables. For the primary outcome measure (seizure status at 1 yr and last follow-up or prior to repeat surgery), patients were dichotomized into seizure free (Engel Class 1A) vs not seizure free (Engel Class IB-IV). Univariate analyses using Fisher's exact test were carried out for binary categorical variables. Logistic regression was used for multicategorical variables and continuous variables to compare the binary outcome. The variables that were considered possible prognostic factors were age, sex, preoperative seizure features, preoperative AED use, preoperative tumor volume, tumor side, insular zone, neuroimaging features, tumor histological subtype and WHO grade, intraoperative protocols utilized, EOR, residual tumor volume, and adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy. EOR was both expressed as a continuous variable as well as categorical variable (>90%, 70%-89%, <70%). Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model to assess the contribution that predictor variables played in time to seizure recurrence, and those who did not have seizure recurrence at last follow-up were censored. Only variables with P-value < .1 from the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate regression model to avoid overfitting. Postoperative AED use was excluded as prognostic factor for seizure outcome since patients who were not seizure free were more likely to be on more AEDs. For variables that are directly related (focal seizure and focal sensory seizure; EOR as continuous variable, category of EOR, and residual tumor volume), only the variable with smaller P-value was included in the multivariate Cox regression. Median time to seizure recurrence and median time to tumor progression were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier (K-M) survival analyses and reported with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Those who did not have seizure recurrence or tumor progression were censored in their respective survival analyses. All statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro (version 13.0; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) software. The threshold for statistical significance was set at a P-value of .05.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

The study population included 284 patients who underwent resection of their insular glioma. Of those, 173 patients (61%) presented with seizures, and 109 had met our inclusion criteria for analysis in the study (Figure 1). Of these 109 patients, 63 (58%) were male and 46 (42%) were female. Median age at surgery was 39 yr (range 17-75 yr), and median age of seizure onset was 37 yr (range 0.4-75 yr). Median seizure duration prior to surgery was 6 mo (range 0.3-492 mo). Seizure frequency varied among the patient cohort; 25 patients (23%) presented with 1 or 2 seizures, 11 (10%) had monthly seizures, and the majority had frequent seizures (26% weekly, 29% daily, and 12% multiple daily). Many patients presented with multiple seizure types, and the most common type was focal seizure (62%) with sensory focal seizure being the most prevalent (52%). Forty-seven percent of the patients had at least 1 generalized seizure and 37% had focal seizures with dyscognitive symptoms. Fifty patients (46%) also had auras accompanying their seizures. The most common aura consisted of unusual sensation in the epigastrium or a “rush” feeling (21%). Other types of auras included a feeling of anxiety and fear (9%), as well as olfactory (11%), gustatory (17%), auditory (4%), and visual (5%) disturbances. Seventy-seven percent of patients had medically refractory seizures given recurrent seizures despite treatment with one or more antiepileptic medications, and 23% had seizures that were controlled with medication. These findings are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics and Seizure Characteristics

| Parameter | No. (%) | 1-yr seizure outcome | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Finala seizure outcome | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sz free | Residual sz | Sz free | Residual sz | ||||||

| N | 109 | 74 (67.9) | 35 (32.1) | 42 (38.5) | 67 (61.5) | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 63 (57.8) | 43 (58.1) | 20 (57.1) | 1.04 (0.46, 2.35) | 1 | 23 (54.8) | 40 (59.7) | 0.82 (0.37, 1.78) | .6915 |

| Femaleb | 46 (42.2) | 31 (41.9) | 15 (42.9) | 19 (45.2) | 27 (40.3) | ||||

| Age at surgery (yr) (median, range) | 39 (17-75) | 39 (23-71) | 41 (17-75) | 0.70 (0.09, 5.12) | .7219 | 38 (23-71) | 41 (17-75) | 1.42 (0.21, 9.66) | .7222 |

| Seizure onset age (yr) (median, range) | 37 (0.4-75) | 37 (3-68) | 35 (0.4-75) | 1.24 (0.11, 14.22) | .8648 | 37 (16-68) | 36 (0.4-75) | 2.70 (0.25, 28.83) | .4099 |

| Seizure duration (mo) (median, range) | 6 (0.3-492) | 6 (0.3-432) | 8 (1-492) | 0.24 (0.02, 3.97) | .3221 | 5 (0.3-168) | 6 (1-492) | 0.13 (0.002, 6.53) | .2859 |

| Seizure type | |||||||||

| Focal | 67 (61.5) | 44 (59.5) | 23 (65.7) | 0.76 (0.33, 1.77) | .6738 | 20 (47.6) | 47 (70.2) | 0.39 (0.17, 0.86) | .0260 c |

| Sensory | 57 (52.3) | 38 (51.4) | 19 (54.3) | 0.89 (0.40, 1.99) | .8388 | 16 (38.1) | 41 (61.2) | 0.39 (0.18, 0.86) | .0297 c |

| Motor | 30 (27.5) | 22 (29.7) | 8 (22.9) | 1.43 (0.56, 3.63) | .4997 | 12 (28.6) | 18 (26.9) | 1.09 (0.46, 2.57) | 1 |

| Focal + dyscognitive | 40 (36.7) | 29 (39.2) | 11 (31.4) | 1.41 (0.60, 3.30) | .5250 | 16 (38.1) | 24 (35.8) | 1.10 (0.50, 2.45) | .8403 |

| Generalized | 51 (46.8) | 31 (41.9) | 20 (57.1) | 0.54 (0.24, 1.22) | .1544 | 20 (47.6) | 31 (46.3) | 1.06 (0.49, 2.29) | 1 |

| Auras | 50 (45.9) | 34 (46.0) | 16 (45.7) | 1.01 (0.45, 2.26) | 1 | 22 (52.4) | 28 (41.8) | 1.53 (0.71, 3.33) | .3260 |

| Olfactory | 12 (11.0) | 9 (12.2) | 3 (8.6) | 1.48 (0.37, 5.83) | .7482 | 6 (14.3) | 6 (9.0) | 1.69 (0.51, 5.65) | .5309 |

| Gustatory | 19 (17.4) | 15 (19.5) | 4 (11.4) | 1.97 (0.60, 6.45) | .2560 | 9 (21.4) | 10 (14.9) | 1.55 (0.57, 4.21) | .4410 |

| Auditory | 4 (3.7) | 3 (4.1) | 1 (2.9) | 1.44 (0.14, 14.33) | 1 | 2 (4.8) | 2 (3.0) | 1.63 (0.22, 12.00) | 1 |

| Visual | 5 (4.6) | 4 (5.4) | 1 (2.9) | 1.94 (0.21, 18.06) | .6699 | 2 (4.8) | 3 (4.5) | 1.07 (0.17, 6.66) | 1 |

| Anxiety | 10 (9.2) | 7 (9.5) | 3 (8.6) | 1.11 (0.27, 4.59) | 1 | 4 (9.5) | 6 (9.0) | 1.07 (0.28, 4.04) | 1 |

| Unusual sensation | 23 (21.1) | 13 (17.6) | 10 (28.6) | 0.53 (0.21, 1.37) | .1884 | 8 (19.0) | 15 (22.4) | 0.82 (0.31, 2.13) | .8107 |

| Seizure frequency | |||||||||

| Once or twiceb | 25 (22.9) | 18 (24.3) | 7 (20.0) | 13 (31.0) | 12 (17.9) | ||||

| Monthly | 11 (10.1) | 8 (10.8) | 3 (8.6) | 1.04 (0.21, 5.08) | .9642 | 4 (9.5) | 7 (10.5) | 0.53 (0.12, 2.27) | .3897 |

| Weekly | 28 (25.7) | 19 (25.7) | 9 (25.7) | 0.82 (0.25, 2.67) | .7431 | 10 (23.8) | 18 (26.9) | 0.51 (0.17, 1.54) | .2347 |

| Daily | 32 (29.4) | 23 (31.1) | 9 (25.7) | 0.99 (0.31, 3.18) | .9917 | 11(26.2) | 21 (31.3) | 0.97 (0.23, 4.15) | .1837 |

| Multiple daily | 13 (11.9) | 6 (8.1) | 7 (20.0) | 0.33 (0.08, 1.35) | .1232 | 4 (9.5) | 9 (13.4) | 0.41 (0.10, 1.69) | .2172 |

| Number of AEDs (median, range) | 1 (0-5) | 1 (0-5) | 1 (0-5) | 0.53 (0.04, 6.77) | .6236 | 1 (1-5) | 1 (0-5) | 0.54 (0.04, 7.42) | .6443 |

| Medically refractory | |||||||||

| Yes | 84 (77.1) | 54 (73.0) | 30 (85.7) | 0.45 (0.15, 1.32) | 0. 2216 | 28 (66.7) | 56 (83.6) | 0.39 (0.16, 0.98) | .0602 |

| Nob | 25 (22.9) | 20 (27.0) | 5 (14.3) | 14 (33.3) | 11 (16.4) | ||||

aFinal seizure outcome at last follow-up or prior to repeat surgery. Sz free = Engel IA; Residual sz = Engel IB-IV.

Odds ratio > 1 = higher likelihood of becoming seizure free. Baseline variable in each category for odds ratio calculation is indicated by b, otherwise presence of a variable is compared to those without. Odds ratios are calculated for the entire range of values in continuous variables.

cIndicates significant P-value.

Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables and logistic regression was used for continuous variables.

Tumor Characteristics

Sixty-four patients (59%) presented with a left-sided lesion. Median size of the lesion was 63 cm3 (range 1.2-211.7 cm3). Tumor location was classified based on the Berger–Sanai insular zone classification system.12 Tumors involving zone I were the most common with 26% of patients demonstrating zone I + IV lesions and 24% of patient with pure zone I lesions. All tumors had FLAIR hyperintensity on preoperative MRI. Nine patients (8%) also had hemorrhage and 33 patients (30%) had enhancement on preoperative MRI (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Tumor Characteristics and Seizure Outcome

| Parameter | No. (%) | 1-yr seizure outcome | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Finala Seizure outcome | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sz free | Residual sz | Sz free | Residual sz | ||||||

| Side of lesion | |||||||||

| Left | 64 (58.7) | 45 (60.8) | 19 (54.3) | 1.31 (0.58, 2.94) | .5386 | 26 (61.9) | 38 (56.7) | 1.24 (0.56, 2.73) | .6904 |

| Rightb | 45 (41.3) | 29 (39.2) | 16 (45.7) | 16 (38.1) | 29 (43.3) | ||||

| Size of lesion (cm3) (median, range) | 63 (1-212) | 62 (1-212) | 63 (5-129) | 4.79 (0.42, 54.09) | .6101 | 53 (1-212) | 67 (5-176) | 0.56 (0.06, 5.09) | .6101 |

| Location by insular zone | |||||||||

| Ib | 26 (23.9) | 18 (24.3) | 8 (22.9) | 12 (28.6) | 14 (20.9) | ||||

| II | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Na | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Na | ||

| III | 8 (7.3) | 5 (6.8) | 3 (8.6) | 0.74 (0.14, 3.88) | .7224 | 2 (4.8) | 6 (9.0) | 0.39 (0.07, 2.30) | .2974 |

| IV | 9 (8.3) | 3 (4.1) | 6 (17.1) | 0.22 (0.04, 1.12) | .0683 | 2 (4.8) | 7 (10.5) | 0.33 (0.06, 1.92) | .2187 |

| I + II | 3 (2.8) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) | 0.89 (0.07, 11.28) | .9276 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (3.0) | 0.58 (0.05, 7.26) | .6752 |

| I + IV | 28 (25.7) | 23 (31.1) | 5 (14.3) | 2.04 (0.57, 7.32) | .2721 | 15 (35.7) | 13 (19.4) | 1.35 (0.05, 9.70) | .5863 |

| II + III | 6 (5.5) | 3 (4.1) | 3 (4.1) | 0.44 (0.07, 2.70) | .3783 | 0 (0) | 6 (9.0) | <0.0001 (0, na) | .9905 |

| III + IV | 10 (9.2) | 8 (10.8) | 2 (5.7) | 1.78 (0.31, 10.32) | .5215 | 5 (11.9) | 5 (7.5) | 1.17 (0.27, 5.02) | .8360 |

| All | 19 (17.4) | 12 (16.2) | 7 (20.0) | 0.76 (0.22, 2.66) | .6698 | 5 (11.9) | 14 (20.9) | 0.42 (0.16, 1.50) | .1799 |

| Imaging features | |||||||||

| Hemorrhage | 9 (8.3) | 7 (9.5) | 2 (5.7) | 1.72 (0.34, 8.86) | .7156 | 3 (7.1) | 6 (9.0) | 0.78 (0.18, 3.31) | 1 |

| Enhancement | 33 (30.3) | 21 (28.4) | 12 (34.3) | 0.76 (0.32, 1.80) | .6557 | 11 (26.2) | 22 (32.8) | 0.73 (0.31, 1.71) | .5248 |

| Tumor pathology | |||||||||

| Diffuse astrocytoma | 22 (20.2) | 14 (18.9) | 8 (22.9) | 0.70 (0.11, 4.48) | .7064 | 9 (21.4) | 13 (19.4) | 1.73 (0.27, 10.97) | .5605 |

| Oligodendroglioma | 25 (22.9) | 16 (21.6) | 9 (25.7) | 0.71 (0.11, 4.44) | .7153 | 8 (19.1) | 17 (25.4) | 1.18 (0.19, 7.42) | .8628 |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 19 (17.4) | 12 (16.2) | 7 (20.0) | 0.69 (0.10, 4.52) | .6950 | 7 (16.7) | 12 (17.9) | 1.46 (0.22, 9.62) | .6950 |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 32 (29.4) | 26 (35.1) | 6 (17.1) | 1.73 (0.27, 11.19) | .5632 | 15 (35.7) | 17 (25.4) | 2.21 (0.37, 13.09) | .3839 |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma | 4 (3.7) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (8.6) | 0.13 (0.01, 2.18) | .1576 | 1 (2.4) | 3 (4.5) | 0.83 (0.05, 13.63) | .8983 |

| Glioblastomab | 7 (6.4) | 5 (6.8) | 2 (5.7) | 2 (4.8) | 5 (7.5) | ||||

| WHO grade | |||||||||

| II | 66 (60.6) | 42 (56.8) | 24 (68.6) | 0.70 (0.13, 3.89) | .6835 | 24 (57.1) | 42 (62.7) | 1.43 (0.26, 7.94) | .6835 |

| III | 36 (30.0) | 27 (38.5) | 9 (25.7) | 1.20 (0.20, 7.30) | .8431 | 16 (38.1) | 20 (29.9) | 2.0 (0.34, 11.70) | .4419 |

| IVb | 7 (6.4) | 5 (6.8) | 2 (5.7) | 2 (4.8) | 5 (7.5) | ||||

| 2016 WHO Classification | .5089 c | .4750 c | |||||||

| Diff. astrocytoma, IDH-mut | 6 (5.5) | 4 (5.4) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (4.5) | ||||

| Diff. astrocytoma, NOS | 16 (14.7) | 10 (13.5) | 6 (17.1) | 6 (14.3) | 10 (14.9) | ||||

| Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mut, 1p/19q codeleted | 10 (9.2) | 7 (9.5) | 3 (8.6) | 4 (9.5) | 6 (9.0) | ||||

| Oligodendroglioma, NOS | 15 (13.8) | 9 (12.2) | 6 (17.1) | 4 (9.5) | 11 (16.4) | ||||

| Oligoastrocytoma, NOS | 19 (17.4) | 12 (16.2) | 7 (20.0) | 7 (16.7) | 12 (17.9) | ||||

| Anapl. astrocytoma, IDH-mut | 8 (7.3) | 8 (10.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (14.3) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

| Anapl. astrocytoma, IDH-WT | 5 (4.6) | 3 (4.1) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (7.1) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

| Anapl. astrocytoma, NOS | 19 (17.4) | 15 (20.3) | 4 (11.4) | 6 (14.3) | 13 (19.4) | ||||

| Anapl. oligoden, IDH-mut, 1p/19q codeleted | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.5) | ||||

| Anapl. oligoden, NOS | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

| GBM, IDH-mut | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | ||||

| GBM, IDH-WT | 4 (3.7) | 3 (4.1) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (4.5) | ||||

| GBM, NOS | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

Diff, diffuse; mut, mutated; WT, wild type; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; NOS, not otherwise specified; anapl, anaplastic; oligoden, oligodendroglioma; GBM, glioblastoma

aFinal seizure outcome at last follow-up or prior to repeat surgery.

Sz free = Engel IA; Residual sz = Engel IB-IV.

Odds ratio > 1 = higher likelihood of becoming seizure free. Baseline variable in each category for odds ratio calculation is indicated by b, otherwise presence of a variable is compared to those without. Odds ratios are calculated for the entire range of values in continuous variables.

cDue to small sample size in each category, Pearson's test was used for comparison.

Other than indicated, Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables and logistic regression was used for continuous variables.

dIndicates significant P-value.

Tumor was classified based on traditional histopathology, and included 22 patients with diffuse astrocytoma (20%), 25 patients with oligodendroglioma (23%), 19 patients with oligoastrocytoma (17%), 32 patients with anaplastic astrocytoma (29%), 4 patients with anaplastic oligodendroglioma (4%), and 7 patients with glioblastoma (6%). This resulted in a total of 66 patients (61%) with WHO grade II, 36 patients (30%) with WHO grade III, and 7 patients (6%) with WHO grade IV tumors. A subset of patients (80 of 109, 73%) was tested for common molecular markers found in gliomas. Based on their molecular and genetic profile, we categorized all patients using the 2016 WHO Classifications of central nervous system tumors using integrated phenotypic and genotypic information.28 We identified 6 patients with IDH-mutated diffused astrocytoma (6%), 10 patients with IDH-mutated, 1p/19q codeleted oligodendroglioma (9%), 8 patients IDH-mutated (7%) and 5 patients with IDH-wild-type (5%) anaplastic astrocytoma, 2 patients with IDH-mutated, 1p/19q codeleted anaplastic oligodendroglioma (2%), and 1 patient with IDH-mutated (1%) and 4 patients with IDH wild-type (4%) glioblastoma. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

Surgical Factors and Outcome

Of the 109 patients, 60 patients (55%) underwent awake surgery with language mapping and 101 (93%) underwent motor mapping. Median extent of resection was 81% (range 32%-100%). Thirty-three patients (30%) had at least 90% resection of their tumor based on postoperative volumetric analysis. Fifty-two patients (48%) had extent of resection reaching 70% to 89% range, and 24 patients (22%) had less than 70% resection of their tumor. Median residual tumor volume was 11 cm3 with range of 0 to 59 cm3. Tumor progression, defined as radiological evidence of tumor growth or enhancement, occurred in 77 patients (71%). Median time to progression was 46 mo (95% CI 37-56 mo). Forty-eight patients (44%) underwent repeat operation for tumor progression. Overall surgical morbidity, defined as long-term neurological deficits, occurred in 2 patients (1.8%) and included hemiparesis and language deficits. Median follow-up duration was 48 mo (range 8-232 mo). At last follow-up, 19 patients (20%) died as a result of their tumor progression.

Seizure Outcome and Predictors of Seizure Freedom

Postoperative seizure outcome was classified according to the Engel seizure outcome scale and dichotomized into those who were completely seizure free (Engel IA) and those who had residual seizures (Engel IB-IV). At 1 yr after surgery, 74 patients (68%) were seizure free and 35 (32%) had residual seizures. Of those who had residual seizures, 22 patients (20%) had nondisabling focal seizures (Engel IB), 6 (6%) had rare disabling seizures (Engel II), 6 (6%) had worthwhile improvement in their seizures (Engel III), and 1 patient (1%) had no improvement in seizures (Engel IV). At last follow-up or prior to repeat surgery, 42 patients (39%) were seizure free and 67 (62%) had seizure recurrence. Forty-two patients (39%) had nondisabling focal seizures, 11 patients (10%) had rare disabling seizures, 10 patients (9%) had seizure improvement, and 4 patients (4%) had no improvement or worse seizure outcome compared to preoperative status (Figure 2). We also compared the postoperative AED use at the last follow-up between the patients were seizure free and those who were not, and found that those who were seizure free were on significantly fewer AEDs and more likely to be completely off medication compared to those with residual seizures (P = .0002; Table 3). The distribution of number of postop AED for both groups is shown in Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2. Of note, the 2 patients with recurrent seizures who were off AED each had a single episode of sensory seizure that did not require chronic AED treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Seizure outcome by Engel Class. Chart showing patients’ seizure outcome based on Engel classification at 1-yr follow-up (white bars) and at last follow-up (black bars). Class IA, completely seizure free; Class IB, nondisabling simple partial seizures; Class II, rare seizures; Class III, meaningful seizure improvement; and Class IV, no seizure improvement or worsening. Numbers above each bar represent the number of patients.

TABLE 3.

Surgical Factors, Surgical Outcome, and Seizure Outcome

| Parameter | No. (%) | Finala seizure outcome | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sz free | Residual sz | ||||

| Side of resection | |||||

| Left | 64 (58.7) | 26 (61.9) | 38 (56.7) | 1.24 (0.56, 2.73) | .6904 |

| Rightb | 45 (41.3) | 16 (38.1) | 29 (43.3) | ||

| Awake surgery | 60 (55.1) | 24 (57.1) | 36 (53.7) | 1.15 (0.53, 2.50) | .8435 |

| Language mapping | 60 (55.1) | 24 (57.1) | 36 (53.7) | 1.15 (0.53, 2.50) | .8435 |

| Motor mapping | 101 (92.7) | 39 (92.9) | 62 (92.5) | 1.05 (0.24, 4.63) | 1 |

| EOR (%) (median, range) | 81 (32-100) | 85 (58-100) | 80 (32-98) | 38.50 (3.55, 417.67) | .0027 c |

| EOR (%) | |||||

| ≥90 | 33 (30.3) | 16 (38.1) | 17 (25.4) | 10.35 (2.09, 51.30) | .0042 c |

| 70-89 | 52 (47.7) | 24 (57.1) | 28 (41.8) | 9.43 (2.01, 44.28) | .0045 c |

| <70b | 24 (22.0) | 2 (4.8) | 22 (32.8) | ||

| Residual tumor volume (cm3) (median, range) | 11 (0-59) | 8 (0-31) | 15 (0-59) | 0.02 (0.002, 0.28) | .0039 c |

| Number of postop AEDs (median, range) | 1 (0-4) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-4) | 0.001 (0.00002, 0.04) | .0002 c |

| Chemotherapy | 93 (85.3) | 37 (88.1) | 56 (83.6) | 1.45 (0.47, 4.53) | .5886 |

| Radiation therapy | 55 (50.5) | 25 (59.5) | 30 (44.8) | 1.81 (0.83, 3.96) | .1339 |

| Tumor progression | 77 (70.6) | 25 (59.5) | 52 (77.6) | 0.42 (0.18, 0.98) | .0533 |

| Time to tumor progression (mo); (median, 95% CI) | 46 (37-56) | 56 (34-84) | 39 (35-53) | .4818 d | |

| Morbidities | 2 (1.8) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.5) | 1.61 (0.01, 26.45) | 1 |

| Follow-up duration (mo) (median, range) | 48 (8-232) | 47 (8-193) | 48 (8-232) | 0.42 (0.06, 3.03) | .3879 |

| Death | 22 (20.2) | 4 (18.2) | 18 (81.8) | 0.29 (0.09, 0.92) | .0300 c |

aFinal seizure outcome at last follow-up or prior to repeat surgery. Sz free = Engel IA; Residual sz = Engel IB-IV.

Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables and logistic regression was used for continuous variables

Odds ratio > 1 = higher likelihood of becoming seizure free. Baseline variable in each category for odds ratio calculation is indicated by b, otherwise presence of a variable is compared to those without. Odds ratios are calculated for the entire range of values in continuous variables.

cIndicates significant P-value.

dLog-rank test used to compare Kaplan–Meir survival functions.

To identify predictors of seizure freedom, we first performed univariate analysis on preoperative seizure characteristics, tumor characteristics, surgical factors, and adjuvant therapy (postoperative chemotherapy or radiation therapy) on final seizure outcome characterized as a dichotomous outcome (seizure free vs residual seizures). Univariate analysis revealed focal seizure type and focal sensory seizures to be associated with seizure recurrence (P = .0260 and P = .0297, respectively, Fisher's exact test; Table 1). Greater extent of tumor resection, expressed both as a continuous and categorical variable, was associated with greater seizure control at last follow-up (P = .0027 and P = .0009, logistic regression; Table 3). Tumor progression trended towards seizure recurrence, but was not statistically significant. Those patients who died were less likely to be seizure free (P = .0300, Fisher's exact test; Table 3). To identify independent predictors of seizure-free outcome, we employed the proportional hazard modeling method using the Cox regression where time to seizure recurrence was used as primary endpoint, and those unrelated univariate analysis predictor variables with P-values < .1 were included in the model. Multivariate regression demonstrated that only greater extent of resection (hazard ratio = 0.2899 [0.1129, 0.7973], P = 0.0174) was a significant predictor of seizure freedom after surgery (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Cox Regression on Independent Predictors of Seizure-Free Outcome

| Predictor variable | HR [95% CI] | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Focal sensory seizures | 1.3984 [0.4269, 1.2052] | .2139 |

| Medically refractory | 1.6284 [0.8454, 3.4066] | .1500 |

| EORa | 0.2899 [0.1129, 0.7973] | .0127 b |

aHR given for entire range of extent of resection.

bIndicates significant P-value.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis using predictor variables with P < .01 from univariate analysis of final seizure outcome. Hazards ratio < 1 means greater likelihood of being seizure free.

Seizure Recurrence and Tumor Progression

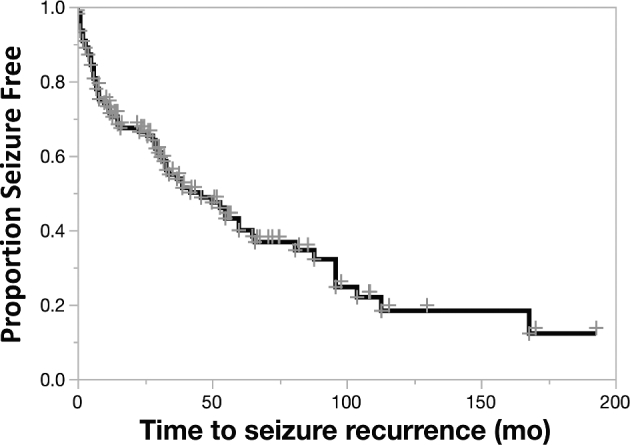

We sought to explore the temporal relationship between seizure recurrence and tumor progression. Median time to seizure recurrence was 46 mo (95% CI 31-65 mo; Figure 3), and that of tumor progression was 46 mo (95% CI 37-56 mo; Table 3). To further investigate this temporal relationship, we found 52 patients who had both seizure recurrence and tumor progression. Using their time to seizure recurrence or/and tumor progression data, we described the frequency of patients who had seizure recurrence at the following time points: 3 to 6 mo prior, 0 to 3 mo prior, 0 to 3 mo after, and 3 to 6 mo after tumor progression (Figure 4). This analysis demonstrated that patients were more likely to have seizure recurrence 0 to 3 mo prior to radiographic evidence of tumor progression.

FIGURE 3.

Time to seizure recurrence. Kaplan–Meir survival curves show time until seizure recurrence. Censored events are shown as + marks.

FIGURE 4.

Association between seizure recurrence and tumor progression. Bar graph showing the distribution of those patients with seizure recurrence at various time points just prior to or after their tumor progression. Numbers above each bar represent the number of patients.

Seizure Outcome for Repeat Surgery

Of the 48 patients who underwent repeat surgery for tumor progression, 22 of these patients had residual seizures prior to repeat resection with >6 mo follow-up. Of these 22 patients, 8 patients (36%) became seizure free after a second operation and 14 (64%) had residual seizures. Univariate analysis of seizure characteristics and tumor features revealed that those with focal seizures were less likely to become seizure free (P = .0364, Fisher's exact test; Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Seizure Outcome After Repeat Surgery for Insular Tumors

| Parameter | No. (%) | Finala seizure outcome | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engel IA | Engel II-IV | ||||

| N | 22 | 8 (36.4) | 14 (63.6) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 11 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 6 (42.9) | 2.22 (0.37, 13.18) | .6594 |

| Femaleb | 11 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) | 8 (57.1) | ||

| Age at surgery (yr) (median, range) | 36 (24-60) | 34 (24-51) | 37 (26-60) | 0.37 (0.01, 9.18) | .5417 |

| Seizure onset age (yr) (median, range) | 30 (16-53) | 31 (18-51) | 30 (16-53) | 0.66 (0.03, 16.03) | .7974 |

| Seizure duration (mo) (median, range) | 55 (24-151) | 47 (26-120) | 68 (24-151) | 0.10 (0.003, 3.92) | .2190 |

| Seizure type | |||||

| Focal | 19 (86.4) | 5 (62.5) | 14 (100.0) | 0 | .0364 c |

| Sensory | 16 (72.7) | 4 (50.0) | 12 (85.7) | 0.17 (0.02, 1.28) | .0704 |

| Motor | 7 (31.8) | 2 (25.0) | 5 (35.7) | 0.6 (0.09, 4.17) | .3496 |

| Focal + dyscognitive | 7 (31.8) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 1.5 (0.24, 9.46) | .6654 |

| Generalized | 7 (31.8) | 2 (25.0) | 5 (35.7) | 0.6 (0.09, 4.17) | .6757 |

| Auras | 9 (40.9) | 3 (37.5) | 6 (42.9) | 0.8 (0.13, 4.74) | .8058 |

| Number of AEDs preop (median, range) | 2 (1-4) | 1.5 (1-3) | 2 (1-4) | 0.62 (0.02, 20.94) | .7920 |

| Side of lesion | |||||

| Left | 13 (59.1) | 4 (50.0) | 9 (64.3) | 0.56 (0.10, 3.25) | .5121 |

| Rightb | 9 (40.9) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | ||

| Size of lesion (cm3) (median, range) | 19.8 (0.6-83.4) | 19.7 (7.1-83.4) | 19.8 (0.6-79.5) | 2.65 (0.17, 40.79) | .4853 |

| Imaging features | |||||

| Hemorrhage | 5 (22.7) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (21.4) | 1.22 (0.16, 9.47) | .8475 |

| Enhancement | 7 (31.8) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (28.6) | 1.50 (0.24, 9.46) | .6654 |

| Tumor pathology | |||||

| Diffuse astrocytoma | 1 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | <0.0001 (0, na) | .9941 |

| Oligodendroglioma | 5 (22.7) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 1.33 (0.11, 15.70) | .8192 |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 5 (22.7) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 1.33 (0.11, 15, 70) | .8192 |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 5 (22.73) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 1.33 (0.11, 15.70) | .8192 |

| Glioblastomab | 6 (27.3) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | ||

| WHO grade | |||||

| II | 11 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 7 (50.0) | 1.14 (0.14, 9.23) | .9006 |

| III | 5 (22.7) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (21.4) | 0.8192 (0.11, 15.70) | .8192 |

| IVb | 6 (27.3) | 2 (25.0) | 4 (28.6) | ||

| Awake surgery | 10 (45.5) | 3 (37.5) | 7 (50.0) | 0.6 (0.10, 3.54) | .5711 |

| Language mapping | 10 (45.5) | 3 (37.5) | 7 (50.0) | 0.6 (0.10, 3.54) | .5711 |

| Motor mapping | 17 (77.3) | 5 (62.5) | 12 (85.7) | 0.28 (0.04, 2.20) | .2113 |

| EOR (%) (median, range) | 74 (7.5-100) | 70 (7.5-100) | 80 (10-100) | 0.34 (0.01, 8.25) | .5043 |

| Residual tumor volume (cm3) (median, range) | 6.0 (0-77.2) | 5.9 (0-77.2) | 6.9 (0-32.0) | 8.49 (0.09, 763.6) | .3515 |

| Morbidities | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (na) | .5152 |

| Number of AEDs postop (median, range) | 2 (1-3) | 1.5 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 0.22 (3.90, 4.58) | .2844 |

| Follow-up duration (mo) (median, range) | 32 (7-101) | 30 (7-42) | 32 (12-101) | 0.03 (0.002, 3.61) | .1505 |

aFinal seizure outcome at last follow-up or prior to repeat surgery. Sz free = Engel IA; Residual sz = Engel IB-IV.

Odds ratio > 1 = higher likelihood of becoming seizure free. Baseline variable in each category for odds ratio calculation is indicated by b, otherwise presence of a variable is compared to those without. Odds ratios are calculated for the entire range of values in continuous variables.

cIndicates significant P-value.

Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables and logistic regression was used for continuous variables.

DISCUSSION

Tumors of the insular region are epileptogenic given the proximity of functionally significant areas and multiple white matter tracts connecting different brain regions.2,3,5 These tumors also remain a challenge to manage given their anatomic complexity, intimate relationship with significant vascular structures, and proximity to eloquent areas.1,4,5 Despite these challenges, aggressive resection of both low- and high-grade insular gliomas may be accomplished safely and increase overall and progression-free survival.12,30 On the other hand, relatively few studies have examined seizure control rates after insular glioma surgery and most focused on low-grade gliomas.17,19 Given advances in glioma treatment and longer survival of this patient population,31 quality of life improvement is a critical factor. Therefore, a better understanding of the relationship between tumor-related seizures and surgery is needed. To our knowledge, this is the largest single-center study to document seizure freedom for both low- and high-grade insular gliomas following surgery with long-term follow-up.

Seizure Predictor Factors

Several previous studies demonstrate good seizure control after low-grade glioma surgery.18,32,33 However, few focus on seizure outcome for resection of insular tumors and mostly involve smaller case series.10,15,17,19 One report involving 52 patients with low-grade gliomas in the insular region found a 67% seizure-free rate.17 Echoing these previous findings, we found that 68% of our patients were seizure free at 1 yr and 88% were free of disabling seizures. Our study also explored long-term seizure-control rates in our patient population, which has rarely been documented systematically. With median follow-up of 46 mo, our analysis showed that at last follow-up time point, 39% patients remained completely seizure free and another 39% only had nondisabling focal seizures. This indicates that insular tumor resection may carry long-term seizure-control benefits, which can significantly improve quality of life for many patients.26 As for predictors of seizure freedom, several previous studies on low-grade gliomas indicated that shorter seizure duration and greater EOR were predictive of seizure control.18,32,33 Based on our multivariate analysis, we found that the extent of surgical resection was a significant predictor of seizure control. In addition, there were only 2 patients who demonstrated long-term deficits in our series; this low-morbidity profile underscores the fact that with meticulous surgical and neuromonitoring techniques, tumors of the insular region can be removed safely. Our results demonstrate that for both low- and high-grade gliomas arising from the insular region, maximizing extent of tumor resection in a safe fashion can significantly improve seizure control and improve quality of life.

Seizure Recurrence and Tumor Progression

We found an association between seizure recurrence and tumor progression. Our analysis demonstrated a very close temporal relationship between seizure recurrence and tumor progression. We found that many of the patients who had tumor progression had seizure recurrence prior to radiographic evidence of progression. Therefore, seizure recurrence may herald tumor progression, and when patients have recurrent seizures, clinicians should perform earlier follow-up imaging to capture early tumor recurrence. For those patients with seizure recurrence and tumor progression, we found that repeat operation may offer additional benefits for seizure control. In fact, 36% of patients with seizures who underwent repeat operation for tumor progression became seizure free after a second operation. While we only found that having focal seizures is a negative predictor of seizure freedom for repeat operation for insular glioma due to the small sample size, based on previous literature,34 we believe that maximizing extent of resection for recurrent insular glioma will not only improve overall survival, but also improve seizure control.9,13,16

Limitations

Limitations of our findings arise from the retrospective nature of the study design and is subject to recall bias and selection bias. We compared the baseline characteristics of those patients included in our study and those excluded and only found small differences in subcategories of seizure frequency (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1), though these are unlikely to represent large baseline differences between the 2 patient populations. Because molecular and genetic testing were not available for routine testing until 2010, not all patients had sufficient molecular tumor markers to be classified according to the 2016 WHO classification scheme. Patients had variable follow-up length and many are lost to follow-up given our tertiary referral pattern. Because postoperative antiepileptic medication management was often done by outside primary care physicians, neurologists, or neuro-oncologists, AED management was not standardized. Therefore, many patients who were seizure free were still maintained on preoperative AED as shown by Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2.

CONCLUSION

Seizures are frequent symptoms associated with insular tumors that significantly impact patients’ quality of life. Maximizing extent of tumor resection favors seizure freedom. Seizure recurrence often occurs prior to tumor progression, and repeat surgery may offer additional benefits for long-term seizure control.

Disclosure

The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article.

Supplementary Material

Notes

The content of this paper was selected as an oral presentation for the 2017 American Association of Neurological Surgeons meeting on April 25, 2017 in Los Angeles, California.

REFERENCES

- 1. Duffau H, Capelle L, Lopes M, Faillot T, Sichez JP, Fohanno D. The insular lobe: physiopathological and surgical considerations. Neurosurgery.2000;47(4):175-184; discussion 810-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Isnard J, Guenot M, Ostrowsky K, Sindou M, Mauguiere F. The role of the insular cortex in temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2000;48(4):614-623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Isnard J, Guenot M, Sindou M, Mauguiere F. Clinical manifestations of insular lobe seizures: a stereo-electroencephalographic study. Epilepsia. 2004;45(9):1079-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yasargil MG, von Ammon K, Cavazos E, Doczi T, Reeves JD, Roth P. Tumours of the limbic and paralimbic systems. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;118(1-2):40-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benet A, Hervey-Jumper SL, Sanchez JJ, Lawton MT, Berger MS. Surgical assessment of the insula. Part 1: surgical anatomy and morphometric analysis of the transsylvian and transcortical approaches to the insula. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(2):469-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moshel YA, Marcus JD, Parker EC, Kelly PJ. Resection of insular gliomas: the importance of lenticulostriate artery position. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(5):825-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lang FF, Olansen NE, DeMonte F et al. Surgical resection of intrinsic insular tumors: complication avoidance. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(4):638-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanai N, Berger MS. Glioma extent of resection and its impact on patient outcome. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(4):753-764; discussion 264-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skrap M, Mondani M, Tomasino B et al. Surgery of insular nonenhancing gliomas: volumetric analysis of tumoral resection, clinical outcome, and survival in a consecutive series of 66 cases. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(5):1081-1093; discussion 1093-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. von Lehe M, Wellmer J, Urbach H, Schramm J, Elger CE, Clusmann H. Insular lesionectomy for refractory epilepsy: management and outcome. Brain. 2009;132(pt 4):1048-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zentner J, Meyer B, Stangl A, Schramm J. Intrinsic tumors of the insula: a prospective surgical study of 30 patients. J Neurosurg. 1996;85(2):263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sanai N, Polley MY, Berger MS. Insular glioma resection: assessment of patient morbidity, survival, and tumor progression. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(1):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hervey-Jumper SL, Berger MS. Role of surgical resection in low- and high-grade gliomas. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(4):284 doi: 10.1007/s11940-014-0284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duffau H. A personal consecutive series of surgically treated 51 cases of insular WHO Grade II glioma: advances and limitations. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(4):696-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duffau H, Capelle L, Lopes M, Bitar A, Sichez JP, van Effenterre R. Medically intractable epilepsy from insular low-grade gliomas: improvement after an extended lesionectomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2002;144(6):563-572; discussion 572-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGirt MJ, Chaichana KL, Attenello FJ et al. Extent of surgical resection is independently associated with survival in patients with hemispheric infiltrating low-grade gliomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(4):700-707;author reply 707-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ius T, Pauletto G, Isola M et al. Surgery for insular low-grade glioma: predictors of postoperative seizure outcome. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(1):12-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pallud J, Audureau E, Blonski M et al. Epileptic seizures in diffuse low-grade gliomas in adults. Brain. 2014;137(pt 2):449-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. von Lehe M, Wellmer J, Urbach H, Schramm J, Elger CE, Clusmann H. Epilepsy surgery for insular lesions. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2009;165(10):755-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berger MS, Ojemann GA. Intraoperative brain mapping techniques in neuro-oncology. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1992;58(1-4):153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duffau H, Peggy Gatignol ST, Mandonnet E, Capelle L, Taillandier L. Intraoperative subcortical stimulation mapping of language pathways in a consecutive series of 115 patients with grade II glioma in the left dominant hemisphere. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(3):461-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hervey-Jumper SL, Li J, Osorio JA et al. Surgical assessment of the insula. Part 2: validation of the Berger-Sanai zone classification system for predicting extent of glioma resection. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(2):482-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanai N, Mirzadeh Z, Berger MS. Functional outcome after language mapping for glioma resection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):18-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berger MS, Deliganis AV, Dobbins J, Keles GE. The effect of extent of resection on recurrence in patients with low grade cerebral hemisphere gliomas. Cancer. 1994;74(6):1784-1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith JS, Chang EF, Lamborn KR et al. Role of extent of resection in the long-term outcome of low-grade hemispheric gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1338-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klein M, Engelberts NH, van der Ploeg HM et al. Epilepsy in low-grade gliomas: the impact on cognitive function and quality of life. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(4):514-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hervey-Jumper SL, Li J, Osorio JA et al. Surgical assessment of the insula. Part 2: validation of the Berger-Sanai zone classification system for predicting extent of glioma resection. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2016;124(2):482-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Engel J Jr, Burchfiel J, Ebersole J et al. Long-term monitoring for epilepsy. Report of an IFCN committee. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;87(6):437-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Simon M, Neuloh G, von Lehe M, Meyer B, Schramm J. Insular gliomas: the case for surgical management. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(4):685-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bourne TD, Schiff D. Update on molecular findings, management and outcome in low-grade gliomas. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(12):695-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang EF, Potts MB, Keles GE et al. Seizure characteristics and control following resection in 332 patients with low-grade gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(2):227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ruda R, Bello L, Duffau H, Soffietti R. Seizures in low-grade gliomas: natural history, pathogenesis, and outcome after treatments. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14 (suppl 4):iv55-iv64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ramakrishna R, Hebb A, Barber J, Rostomily R, Silbergeld D. Outcomes in reoperated low-grade gliomas. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(2):175-184; discussion 184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.