Abstract

Fragile X syndrome is rare but a prominent cause of intellectual disability. It is usually caused by a de novo mutation that occurs on multiple haplotypes and thus would not be expected to be detectible using genome-wide association (GWA). We conducted GWA in 89 male FXS cases and 266 male controls, and detected multiple genome-wide significant signals near FMR1 (odds ratio=8.10, P=2.5×10−10). These findings withstood robust attempts at falsification. Fine-mapping yielded a minimum P=1.13×10−14 but did not narrow the interval. Comprehensive functional genomic integration did not provide a mechanistic hypothesis. Controls carrying a risk haplotype had significantly longer FMR1 CGG repeats than controls with the protective haplotype (P=4.75×10−5) which may predispose toward increases in CGG number to the pre-mutation range over many generations. This is a salutary reminder of the complexity of even “simple” monogenetic disorders.

Introduction

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) 1 is rare (0.25–1/1,000 male births) but a prominent cause of intellectual disability 2,3. It is characterized by intellectual disability, autistic behavior, hyperactivity, anxiety, and a range of physical abnormalities (e.g., tall stature, macroorchidism) 4. FXS is caused by CGG expansion in the 5’ UTR of the chromosome X gene FMR1 in most cases. 5–7 Full FXS mutations are characterized by expansion of the FMR1 5’ UTR CGG repeat to ≥200 copies with pre-mutations in the 55–200 copy range 8.

FMR1 5’ UTR CGG expansions generally arise de novo when mutable pre-mutations expand to full mutations during oogenesis. Although the probability of de novo mutations can be influenced by local DNA features, detection of de novo events using linkage disequilibrium would be unexpected for high-penetrance single gene disorders 9,10. This implies that genome-wide association (GWA) of FXS cases versus controls should not detect the FRM1 region as a susceptibility locus for FXS. As part of a study of FXS and autism, we conducted a case-control GWAS for FXS and found a strong common-variant association signal near FMR1 that withstood efforts at falsification. We determined that this association was consistent with case-control association studies using small numbers of microsatellite markers from the 1990s.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Males with a genetically-confirmed diagnosis of FXS were recruited from volunteer registries (URLs). All available medical records were reviewed, and any features suggestive of a complex or atypical presentation led to exclusion. Controls were from the Genes and Blood Clotting Study (GABC) in dbGaP (URLs, accession phs000304.v1.p1). GABC participants were male university students who volunteered for a study of the genetics of hemostasis and who had no acute or chronic illnesses. Additional male comparison subjects were from the Swedish Schizophrenia Study (N=3,525, 46.4% cases); briefly, these subjects were sampled from population registers and non-European ancestry outliers were removed, and we selected males genotyped with OmniExpress arrays. 11 As we found no evidence for association with schizophrenia in the FMR1 region in this sample or in the literature, 11,12 cases and controls were combined. We also used male HapMap3 founders from northwestern Europe and Tuscany (CEU and TSI, N=101). 13 All procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents/legal guardians of FXS cases and from control subjects.

Genetic assays.

Table 1 summarizes the samples and assays used in this study. Cases and controls were randomized where possible and analyses were performed blinded to case/control status where possible. FMR1: the number of CGG repeats in the 5’UTR of FMR1 was determined in 89 FXS cases with a validated diagnostic assay (Kimball Genetics, Denver, CO). 14–16 To understand the internal structure of FMR1 CGG repeats and to place these on common haplotypes, we used AmplideX FMR1 PCR kits (Asuragen, Inc; Austin, TX; catalog #49402) to quantify FMR1 5’UTR repeat sizes and to count AGG interruptions. GWAS: FXS cases and GABC controls were genotyped with Illumina HumanOmni1-Quad arrays, and genotypes were called using predefined clusters using GenomeStudio. Quality control was performed using PLINK. 17 SNPs were excluded for missingness > 0.03, minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01, deviation from Hardy-Weinberg expectations in controls (P < 1×10−6), SNP missingness differences between cases and controls (P < 0.05), or if a SNP probe did not map uniquely to the human genome. Subjects were excluded for missingness > 0.05, excessive autosomal homozygosity or heterozygosity, or relatedness (> 0.2 based on LD pruned autosomal SNPs). One FXS case was genotyped in duplicate with 0.99998 concordance, and a CEPH sample previously assayed with the same array had 0.99981 concordance. TaqMan: rs2197706 and rs5905149 genotypes were verified with TaqMan Assays (catalog #4351379 and #4351379, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). A SNP from Gerhardt et al. 18 (rs45631657) was genotyped with a custom TaqMan assay. Sequenom: we designed two massARRAY iPLEX (San Diego, CA) genotyping panels for common variant fine-mapping. SNPs were selected from GWAS results, haplotype analyses, and common variation databases, and then pruned using TAGGER. 19 All assays used genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood. The genome reference was GRCh37/UCSC hg19.

Table 1.

Summary of samples and genotyping.

| Purpose | Genotyping | FXS Cases | Controls | Control source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establish FXS status | FMR1 5’UTR CGG repeat (CLIA assay) | 89 | 0 | N/A |

| FMR1 CGG repeat analysis | 82 † | 109 | Sweden | |

| GWAS | Illumina HumanOmni1-Quad | 89 | 266 | GABC |

| Allele frequency comparisons | Illumina Human1M & Affymetrix 6.0 | – | 101 | HapMap3 |

| Illumina OmniExpress | – | 3,525 | Sweden | |

| Verify key genotypes and allele assignments | TaqMan rs2197706 | 82 † | 0 ‡ | N/A |

| TaqMan rs5905149 | 82 † | 94 ‡ | Sweden | |

| Common variant fine-mapping | Sequenom (31 SNPs) | 89 | 467 | Sweden |

| TaqMan rs45631657 | 103 | 467 | Sweden |

insufficient DNA for 7 FXS cases.

The purpose of genotyping was to verify allele assignments; as rs5905149 verified in cases and controls and as rs2197706 verified in cases, we were confident that allele misidentification did not explain case-control differences.

Statistical analysis.

Case-control comparisons were performed using PLINK 17 using logistic regression under an additive model with three ancestry principal components as covariates. Bioinformatic integration included a range of functional genomic results from fetal brain (see Supplemental Methods).

Results

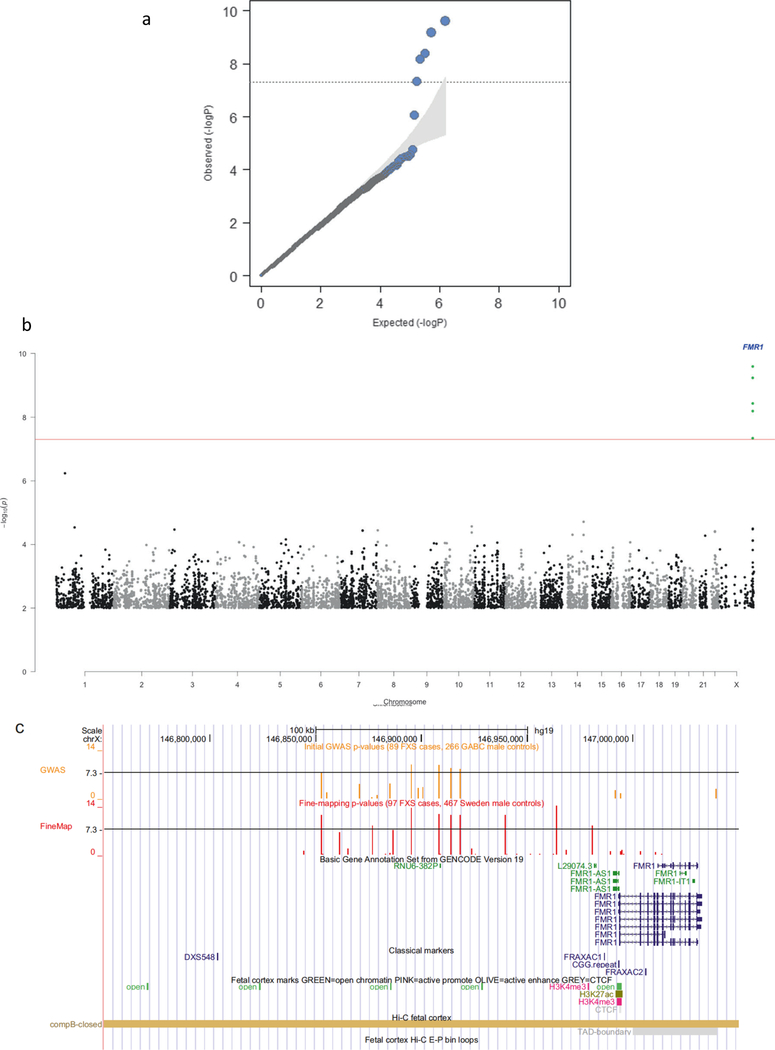

We conducted GWA analyses for 750K SNPs in 89 male FXS cases and 266 male controls (Table S1). All FXS cases had full FMR1 mutations (>200 CGG repeats) as determined using a validated diagnostic assay meeting US governmental standards for accuracy and reliability (we verified these findings using a second assay in 82 FXS cases with sufficient DNA). We assessed ancestry using principal components analysis 20 on LD-pruned autosomal SNPs (Figure S1). All controls and 90% of cases were of predominant European ancestry (we retained nine cases of mixed ancestry given the small number of cases). Logistic regression analyses identified five SNPs that met genome-wide significance with odds ratios > 5 (Table 2, Figures 1a-b). These SNPs were in a 66 kb interval from chrX:146.85–146.92 Mb located 75 kb 5’ of the nearest gene, FMR1. Repeating the logistic regression conditioning on the most strongly associated SNP (rs2197706) markedly attenuated significance in the FMR1 region suggesting the presence of a single association signal.

Table 2.

Genome-wide significant results of GWAS of male FXS cases and controls.

| SNP | chrX (hg19) | Alleles | OR (95% CI) | P | Fcase | Fcontrol | FSweden | FCEU | FTSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs5952060 | 146852679 | C/T | 5.33 (2.93–9.71) | 4.57×10−8 | 0.764 | 0.365 | 0.357 | 0.386 | 0.409 |

| rs2197706 | 146895120 | A/C | 8.10 (4.24–15.49) | 2.53×10−10 | 0.807 | 0.351 | – | 0.357 | 0.386 |

| rs5905149 | 146908213 | A/C | 5.99 (3.40–10.56) | 5.76×10−10 | 0.584 | 0.184 | 0.183 | – | – |

| rs7876251 | 146913828 | G/A | 5.64 (3.17–10.01) | 3.68×10−9 | 0.693 | 0.286 | 0.279 | 0.263 | 0.279 |

| rs4824253 | 146918268 | G/A | 5.35 (3.04–9.43) | 6.41×10−9 | 0.685 | 0.286 | 0.278 | 0.263 | 0.296 |

The first allele given is the least common in this sample and is the reference for the odds ratio (OR) and frequencies. CI is confidence interval. P is from the logistic regression including ancestry covariates. Logistic regression P-values after removing nine cases with divergent ancestry were 5.86×10−8, 3.36×10−10, 8.52×10−10, 4.79×10−9, and 8.38×10−9 (respectively). Shown are allele frequencies for male FXS cases (Fcase), GABC controls (Fcontrol), subjects from Sweden (FSweden), and HapMap3 northwestern European (FCEU) and Tuscan control samples (FTSI).

Figure 1. FXS case-control GWAS.

(A) Quantile-quantile plot for logistic regression of male FXS cases and GABC controls (including ancestry principle components). The observed P-values conform closely to the null except for five SNPs in the FMR1 region. The shaded region indicates the expected 95% probability interval for ordered P-values. (B) Manhattan plot for the GWAS of male FXS cases and GABC controls (logistic regression including ancestry principle components). The X-axis is chromosomal position from 1ptel to Xqtel. The Y-axis is -log10(P). Genome-wide significant SNPs near FMR1 are indicated. (C) Detail of FMR1 region (hg19, chrX:146850000–147040000). Tracks are: GENCODE gene annotations; positions of FRAXAC1, FRAXAC2, and promoter CGG repeat; selected ChIP-seq marks; SNP positions and -log10(P) for SNPs in the fine-mapping study and in the GWAS; DNA-DNA chromosomal looping from 5C based on the FMR1 promoter; and open chromatin in pre-frontal cortex of 9 adult schizophrenia (SCZ) cases and 9 fetal samples.

Given that FXS usually results from de novo mutations, strong associations with common SNPs could be considered unexpected. Indeed, the strongest association (rs2197706, odds ratio=8.10, P=2.5×10−10) is among the top dichotomous trait associations in the GWAS catalog 21 (URLs). We therefore evaluated alternative explanations for these findings. First, given the marked allele frequency differences in cases and controls, re-genotyping rs5905149 and rs2197706 with TaqMan assays showed perfect agreement with Illumina array genotypes, and served to exclude allele assignment errors. Second, the allele frequencies in cases and controls were similar genome-wide except for SNPs 5’ of FMR1 (Figure S2). Given our use of controls genotyped independently from cases, it is important to note that the control allele frequencies for the significant SNPs in the FMR1 region were similar to those from two external samples (Table 2). Third, genome-wide P-values conformed closely to the null expectation (mean P-value=0.500 over 750K SNPs, Figure 1a), findings inconsistent with uncontrolled bias. Fourth, exclusion of nine cases with mixed ancestry had little impact on the results (Table 2). Fifth, a trivial explanation for these findings is if cases were cryptically related via a recent shared ancestor; however, case-case pairs were slightly less related on average than control-control pairs (Figure S3). Cases and controls had similar proportions of autosomal homozygous SNPs as well as the number and size of autosomal runs of homozygosity (no comparisons were significantly different and cases had lower means in each instance). Sixth, asymptotic P-values can be inaccurate in small samples, but Fisher’s exact test and permutation procedures yielded similar significance levels. Thus, we could identify no plausible alternative explanation for our findings.

In a fine-mapping experiment, we genotyped 32 SNPs (chrX:146844358–147013704, the association region extending into FMR1) in an expanded but overlapping set of 89 FXS cases (27 new male FXS male cases plus 62 of the 89 original FXS cases) along with 467 male controls from a different study than for the initial GWAS (see Table 2). We included rs45631657 which was reported to inactivate an important replication origin. 18 Variable numbers of SNPs were genotyped twice on the same subjects, and we observed 100% agreement (data not shown). Nine SNPs exceeded genome-wide significance (Table S2). Analyses of all five SNPs in Table 2 yielded consistent odd ratios and greater significance (P-values ranging from 4×10−12 to 7×10−14), and four other SNPs reached genome-wide significance (rs4824231, P=1.13×10−14; rs25705, P=5.74×10−9; rs45631657, P=5.20×10−12; and rs112146098, P=6.60×10−9). Repeating the logistic regression conditioning on rs2197706 or rs4824231 markedly attenuated significance in the FMR1 region again suggesting the presence of a single association signal. Thus, we continued to observe a broad region of significance.

Figure 1c depicts the association region. The association region includes the FMR1 promoter CGG repeat. Table 3 shows haplotypes from the genome-wide significant SNPs, and the LD matrix of pairwise r2 values is given in Table S3. The most common haplotype was strongly protective, and there were two risk haplotypes. FRM1 CGG analysis was available on 109 controls (selected to represent the most common haplotypes). Controls with the risk haplotype had significantly longer CGG repeats (mean 33.7, SD 6.9, N=53) than controls with the protective haplotype (mean 28.7, SD 5.3, N=56; F1,107=18.7, P=3.52×10−5). Around 40% of cases had additional phenotype measures (e.g., Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale and the Social Responsiveness Scale) and there were no significant differences between cases with the risk or protective haplotypes (data not shown).

Table 3.

Haplotype analyses of FMR1 region.

| Haplotype | Subjects | Controls | FXS cases | Freq control | Freq case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGACGGTCC | 17 | 14 | 3 | 0.030 | 0.031 |

| CGACGGTCC | 20 | 17 | 3 | 0.036 | 0.031 |

| CGAAGGTTT | 21 | 20 | 1 | 0.043 | 0.010 |

| CGACAATTC | 26 | 17 | 9 | 0.036 | 0.093 |

| CGCCAATCC | 31 | 29 | 2 | 0.062 | 0.021 |

| CGAAGGTTC | 65 | 42 | 23 | 0.090 | 0.237 |

| CCAAGGCTT | 77 | 44 | 33 | 0.094 | 0.340 |

| TGCCAATCC | 261 | 250 | 11 | 0.535 | 0.113 |

Observed haplotypes from fine-mapping data (32 SNPs in 89 FXS cases and 467 male controls). Haplotypes were created using nine genome-wide significant SNPs (rs5952060-rs112146098-rs2197706-rs5905149-rs7876251-rs4824253-rs45631657 -rs4824231-rs25705). Haplotypes counts <10 (N=46) were removed. Logistic regression highlighted a strongly protective haplotypes (green) and two risk haplotypes (red).

We next evaluated possible functions of the association region using functional genomic data. Using RNA-seq data from human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in nine schizophrenia cases and nine controls along with prefrontal cortex (PFC) from nine fetuses and three neural progenitor cell lines, we saw that FMR1 (but not the antisense transcript, FMR1-AS1) was robustly expressed (Figure S4). There was no evidence of substantial gene expression or an unannotated feature in the association region 5’ to FMR1. The expression of FMR1 in DLPFC is associated with a common genetic variant but the associated SNP is far outside the region. 22 We evaluated functional genomic data from fetal brain 23. As expected, the FMR1 transcriptional start site had a pattern of open chromatin and H3K27ac and H3K4me3 histone marks consistent with an actively transcribed gene. The 5’ association region had several additional open chromatin regions, but these are common in the genome and there were no suggestions of a distal enhancer-promoter regulatory mechanism (i.e., the open chromatin regions did not have H3K4me marks or evidence of distal chromatin loop interactions using Hi-C; Figure 1c). The SNPs associated with FXS were not notable for open chromatin or key ChIP-seq marks.

Discussion

GWA of FXS cases versus controls identified an unusually strong association with the FMR1 region. The largest association (odds ratio=8.10, P=2.5×10−10) is among the top dichotomous trait associations in the EBI GWAS catalog 21 (URLs), and generally exceeded only by rare adverse drug reactions. Given the small sample size (89 FXS cases and 266 male controls), it is notable that the association survived robust attempts at falsification, and became more significant in a fine-mapping experiment with some new cases and independent controls.

In some respects, it was unexpected to identify the causal locus for FXS (a rare, single-gene disorder) in an outbred population using linkage disequilibrium-based GWA. GWA in case-control samples can detect rare causal genes in special circumstances that do not apply here (e.g., if sample size is very large, if cases inherit a causal mutation from a relatively recent common ancestor 24,25, or if multiple rare mutations yield an aggregate signal detectible by GWA 26). De novo mutations in particular may be invisible to GWA: although de novo mutational processes can be influenced by local genomic context, replication timing, and genotypes at other loci 9,10,27–29, these effects are generally not deterministic, and most de novo mutations occur on different haplotypes.

With the exception of unusual exonic mutations, FXS is caused by a de novo mutational event in the expansion of a pre-mutation to a full mutation during oogenesis 5–7. However, the local genomic context of FMR1 de novo promoter mutations is influential 30–32. In fact, our finding could be anticipated given the literature from the 1990s: there is substantial evidence that this region is detectible via linkage disequilibrium in case-control studies using a few microsatellite markers 32–37. Indeed, a 1992 paper 34 reported a FXS case versus control haplotype difference as “P<0.001” but the P-value actually reached genome-wide significance (P ~9×10−9). The association of common variation upstream of FMR1 with FXS has strong replication evidence in the literature: this is unquestionably a replicated association.

Fine-mapping of the interval and integration with a number of types of functional genomic data did not narrow the region or yield a mechanistic hypothesis. A lack of early fetal data limits this conclusion. It is possible that a population genetic mechanism is at work: the risk haplotype is present in ~18% of European-ancestry controls, and tends to carry a greater number of CGG repeats which may predispose toward increases in CGG number to the pre-mutation range over many generations. Similar mechanisms may apply for repeat expansions in Huntington’s disease 38 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. 39 These findings also suggest a potential clinical use of FMR1 region haplotype data. For example, if SNP array or whole genome sequencing data are consistent with the FXS risk haplotype, subjects with a risk haplotype and features of FXS could reasonably be prioritized for testing for the presence of the causal FMR1 CGG repeat (a specialized test not readily obtainable otherwise).

This is a salutary reminder of the complexity of even “simple” monogenetic disorders, and of the continuing importance of robust findings from older papers before the advent of high-throughput/high-resolution genomic methods. Publication of our finding will allow inclusion in the EBI GWAS catalog, and maximize the chances that these older but highly relevant papers remain known to the community.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by an Autism Speaks award to PFS. PFS gratefully acknowledges support from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, award D0886501). We are indebted to Dr Mark Daly for discussions regarding the results, and to senior FXS researchers for comments after this paper appeared on bioRxiv. For the human postmortem samples, the authors acknowledge the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office and the families of the deceased. They also note contributions of Drs. James Overholser and George Jurjus and of Lesa Dieter in the retrospective psychiatric assessments, and Dr. Grazyna Rajkowska and Gouri Mahajan in sample preparation – this work was supported by NIH/NIGMS COBRE Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience (P30 GM103328).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

PFS is a scientific advisor for Lundbeck.

URLs

dbGaP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap

Fragile X Research Registry, https://www.fragilexregistry.org

EBI/NHGRI GWAS catalog, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas

References

- 1.Bhakar AL, Dolen G & Bear MF The pathophysiology of fragile X (and what it teaches us about synapses). Annu Rev Neurosci 35, 417–43 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner G, Webb T, Wake S & Robinson H Prevalence of fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet 64, 196–7 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman SL Epidemiology. in Fragile X Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment and Research (eds. Hagerman R & Hagerman P) 136–168 (The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terracciano A, Chiurazzi P & Neri G Fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 137, 32–7 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberle I et al. Instability of a 550-base pair DNA segment and abnormal methylation in fragile X syndrome. Science 252, 1097–102 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verkerk AJ et al. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell 65, 905–14 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu S et al. Fragile X genotype characterized by an unstable region of DNA. Science 252, 1179–81 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin P, Alisch RS & Warren ST RNA and microRNAs in fragile X mental retardation. Nat Cell Biol 6, 1048–53 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veltman JA & Brunner HG De novo mutations in human genetic disease. Nat Rev Genet 13, 565–75 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Exome Aggregation Consortium et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536, 285–91 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ripke S et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet 45, 1150–9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511, 421–7 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altshuler DM et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature 467, 52–8 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor AK et al. Molecular predictors of cognitive involvement in female carriers of fragile X syndrome. Jama 271, 507–14 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merenstein SA et al. Molecular-clinical correlations in males with an expanded FMR1 mutation. Am J Med Genet 64, 388–94 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loesch DZ, Huggins RM, Bui QM, Taylor AK & Hagerman RJ Relationship of deficits of FMR1 gene specific protein with physical phenotype of fragile X males and females in pedigrees: a new perspective. Am J Med Genet A 118, 127–34 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang CC et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, 7 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerhardt J et al. Cis-acting DNA sequence at a replication origin promotes repeat expansion to fragile X full mutation. J Cell Biol 206, 599–607 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J & Daly MJ Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21, 263–5 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Price AL et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 38, 904–9 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hindorff LA et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 9362–7 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fromer M et al. Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nature Neuroscience 19, 1442–1453 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giusti-Rodríguez P et al. Schizophrenia and a high-resolution map of the three-dimensional chromatin interactome of adult and fetal cortex (Submitted).

- 24.Peltonen L, Jalanko A & Varilo T Molecular genetics of the Finnish disease heritage. Hum Mol Genet 8, 1913–23 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Struewing JP et al. The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med 336, 1401–8 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson CA, Soranzo N, Zeggini E & Barrett JC Synthetic associations are unlikely to account for many common disease genome-wide association signals. PLoS Biol 9, e1000580 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg IL et al. PRDM9 variation strongly influences recombination hot-spot activity and meiotic instability in humans. Nature genetics 42, 859–63 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hastings PJ, Lupski JR, Rosenberg SM & Ira G Mechanisms of change in gene copy number. Nat Rev Genet 10, 551–64 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koren A et al. Differential relationship of DNA replication timing to different forms of human mutation and variation. Am J Hum Genet 91, 1033–40 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Libby RT et al. CTCF cis-regulates trinucleotide repeat instability in an epigenetic manner: a novel basis for mutational hot spot determination. PLoS Genet 4, e1000257 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brock GJ, Anderson NH & Monckton DG Cis-acting modifiers of expanded CAG/CTG triplet repeat expandability: associations with flanking GC content and proximity to CpG islands. Hum Mol Genet 8, 1061–7 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eichler EE et al. Length of uninterrupted CGG repeats determines instability in the FMR1 gene. Nat Genet 8, 88–94 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu YH et al. Variation of the CGG repeat at the fragile X site results in genetic instability: resolution of the Sherman paradox. Cell 67, 1047–58 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richards RI et al. Evidence of founder chromosomes in fragile X syndrome. Nat Genet 1, 257–60 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haataja R, Vaisanen ML, Li M, Ryynanen M & Leisti J The fragile X syndrome in Finland: demonstration of a founder effect by analysis of microsatellite haplotypes. Hum Genet 94, 479–83 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiurazzi P, Macpherson J, Sherman S & Neri G Significance of linkage disequilibrium between the fragile X locus and its flanking markers. Am J Med Genet 64, 203–8 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gunter C et al. Re-examination of factors associated with expansion of CGG repeats using a single nucleotide polymorphism in FMR1. Hum Mol Genet 7, 1935–46 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warby SC et al. CAG expansion in the Huntington disease gene is associated with a specific and targetable predisposing haplogroup. Am J Hum Genet 84, 351–66 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mok K et al. Chromosome 9 ALS and FTD locus is probably derived from a single founder. Neurobiol Aging 33, 209 e3–8 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.