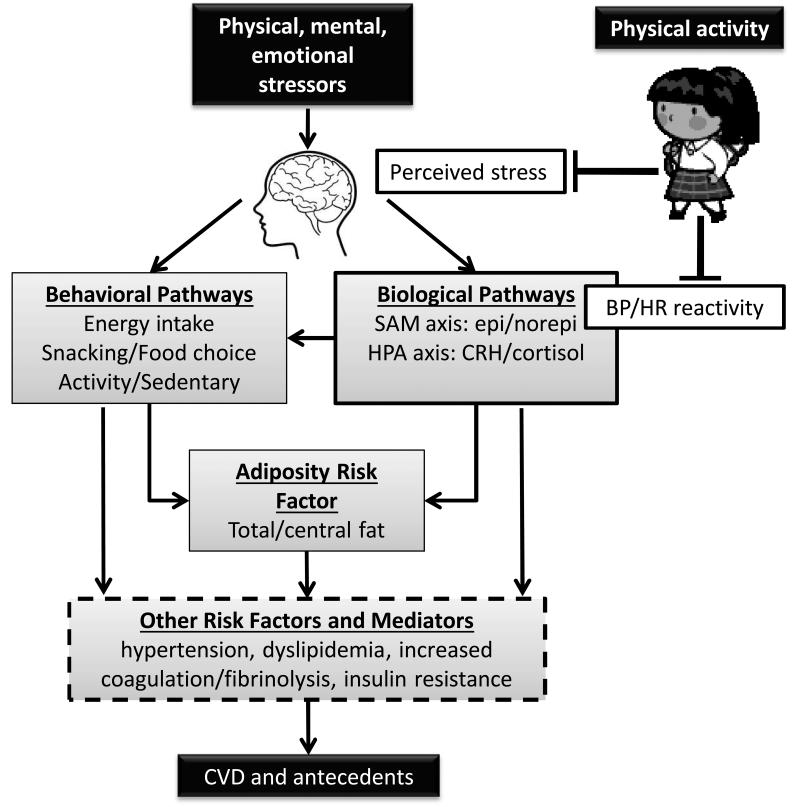

Figure 1.

Schematic of proposed behavioral and physiological pathways by which stress may promote CVD risk factors in youth. Environmental events that can act as physical, mental, or emotional stressors are interpreted and evaluated in the brain and assessed as to whether it is perceived as a stressor. Stressful events can initiate a host of behavioral, endocrine, and autonomic responses and coping mechanisms. Behavioral coping responses include greater energy intake through increased eating and a shift in food choice toward more energy dense comfort foods, especially in those children who restrain their dietary intake. Stress also increases youth's coping by engaging in distracting sedentary behaviors such as watching television and reduces willingness to engage in exercise. These stress coping behaviors increase the risk of excessive weight gain. Stress activates the sympatho-adrenal-meduallary (SAM) axis resulting in increased heart rate, myocardial contractility, vasodialtion/constriction and increased diastolic and systolic blood pressure. Stress also activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which stimulates cortisol secretion, which shifts food choice towards comfort foods, promotes the deposition of body fat, especially abdominal fat. The effects of unhealthy stress coping behaviors and of stress-induced activation of the SAM and HPA axes on CVD risk factors are mediated through increases in adiposity and then through obesity-related comorbidities or mediated more directly through stress effects on blood pressure, blood lipid concentrations, coagulation/fibrinolysis states, etc. Physical activity, such as interval exercise that mimics children's natural pattern of play or a self-paced 1 mile walk that models a walk to school dampen perceived stress or the assessment of whether the stressor is as threatening, and blood pressure reactivity when children encounter a cognitive or interpersonal stressor. Dampening perceived stress reactivity and resultant blood pressure reactivity to a stressor may be one way that exercise produces a cardio-protective effect.