SUMMARY

Background:

Physicians may be reluctant to prescribe combined immunosuppression in older patients with Crohn’s disease due to perceived risk of treatment-related complications.

Aims:

We evaluated the impact of age on risk of Crohn’s disease-related complications in patients treated with early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management in a post-hoc analysis of the Randomized Evaluation of an Algorithm for Crohn’s Treatment (REACT) cluster randomized trial.

Methods:

We compared efficacy (time to major adverse outcome of Crohn’s disease-related surgery, hospitalization or serious complications; corticosteroid-free clinical remission) and safety outcomes at 24 months, between patients aged <60y vs. ≥60y randomized to early combined immunosuppression or conventional management, using Cox proportional hazard analysis or modified Poisson model. In the early combined immunosuppression arm, patients with failure to achieve clinical remission within 4–12 weeks of corticosteroids were treated with combination of tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist + antimetabolite and sequentially escalated in a stepwise algorithm.

Results:

Of 1981 patients, 311 were ≥60y (15.7%; 173 randomized to early combined immunosuppression and 138 to conventional management). Over 24 months, 10% of older patients developed Crohn’s disease-related complications (early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management: 6.4% vs. 14.5%) and 14 patients died (3.5% vs. 5.8%). There was no difference between younger and older patients in risk of achieving corticosteroid-free clinical remission (<60y, early combined immunosuppression (72.6%) vs. conventional management (64.4%): relative risk [RR], 1.06 [95% confidence interval, 0.98–1.15] vs. ≥60y, early combined immunosuppression (74.8%) vs. conventional management (63.0%): RR, 1.09 [0.90–1.33], p-interaction=0.78) or time to major adverse outcome (<60y: hazard ratio [HR], 0.71 [0.53–0.96] vs. ≥60y: HR, 0.69 [0.31–1.51], p-interaction=0.92) with early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management.

Conclusions:

We observed no difference in efficacy and safety of early combined immunosuppression compared to conventional management in older and younger patients. Early combined immunosuppression may be considered as a treatment option in selected older patients with Crohn’s disease with suboptimal disease control.

Keywords: Treatment strategy, aging, comparative effectiveness, inflammatory bowel disease

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 10–30% patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are older than 60 years, and with an aging population and chronic nature of IBD, the prevalence of IBD in older adults is anticipated to continuously rise.1, 2 Based on the 2015 National Health Interview Survey, an estimated 1.7% adults ≥65y (approximately 805,000) reported a diagnosis of IBD.3 Several cross-sectional studies and European registries have reported differences in disease phenotype and behavior in older and younger patients with IBD.4–7 While older patients may have less aggressive behaviour, they are more likely to be hospitalized and have similar rate of surgical intervention compared to younger patients. In a nationally representative longitudinal study of hospitalized adults, we observed that older patients with IBD have higher annual burden and costs of hospitalization, and higher in-hospital mortality, as compared to younger patients.8

Since older patients comprise <5% of participants in clinical trials, evidence base to guide treatment strategies in this cohort is limited, with real-life practice trends towards long-term corticosteroid use and limited use of steroid-sparing agents.9–11 Due to systematic differences between older versus younger patients in risks of disease-related complications, treatment-related complications and extra-intestinal complications (e.g., cardiovascular disease, malignancy), there is limited understanding of risk-benefit trade-offs of different therapies and treatment strategies. In younger patients at high-risk of disease complications and relative paucity of concomitant comorbidity, aggressive therapy with combination of biologics and anti-metabolites is preferred.12 However it is unclear whether this strategy can be directly extrapolated to older patients who may be more susceptible to treatment-related complications and non-Crohn’s disease-related complications associated with comorbidity.

In an attempt to address this question, we performed a post-hoc analysis of Randomized Evaluation of an Algorithm for Crohn’s Treatment (REACT) trial, a cluster-randomized trial comparing early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management in patients with Crohn’s disease.13 Specifically, we compared efficacy and safety outcomes between in younger (<60y) vs. older patients (≥60y) with Crohn’s disease.

METHODS

Data Source

In the REACT trial, between March 2010 and October 2013, 41 community gastroenterology practices from Belgium and Canada were randomly assigned to either early combined immunosuppression (n=22) or conventional management (n=19).13 These practices enrolled up to 60 consecutive adult patients with Crohn’s disease, regardless of baseline disease activity or medication exposure, who had been seen within the previous 12 months or who attended the clinic during the study period. A computer-generated minimization procedure balanced treatment effects of country and practice size (≤100 Crohn’s disease patients treated annually) between intervention groups. Because of the complex multidrug algorithm that was evaluated, masking of participants, providers, or assessors to group assignment was not possible. To minimize risk of bias related to the open-label nature of the trial, the outcome measures were objective and, to avoid the potential for treatment contamination, individual practices were unaware of the assignment of other practices.14 The original trial was approved by the Canadian Shield Research Ethics Board, and institutional consent was obtained in Belgium. All participants provided written informed consent.

The original trial was designed to evaluate the impact of a strategy of algorithmic early combined immunosuppression approach vs. conventional management in achieving corticosteroid-free clinical remission and risk of composite major adverse outcomes including time to Crohn’s disease-related surgery, hospitalization or Crohn’s disease-related complications, over 24 months. The key findings of the trial were: (1) there was no significant difference in the rate of steroid-free clinical remission in the two groups (early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management: 66% vs. 62%) at 12 months, which was the primary outcome of the study; (2) the time to occurrence of Crohn’s disease-related surgery and serious Crohn’s disease-related complications (abscess, fistula, stricture, serious worsening of disease activity or extra-intestinal manifestations) were significantly less in practices randomized to early combined immunosuppression (hazard ratio [HR], 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.69 (0.50–0.97) and 0.73 (0.61–0.87), respectively); and (3) there was no difference in serious drug-related adverse events including infections between the two groups (0.9% vs. 1.1%).

Patients

For this post-hoc analysis, patients were classified as younger (<60y) or older (≥60y, population of interest) based on age at time of enrollment into the trial.

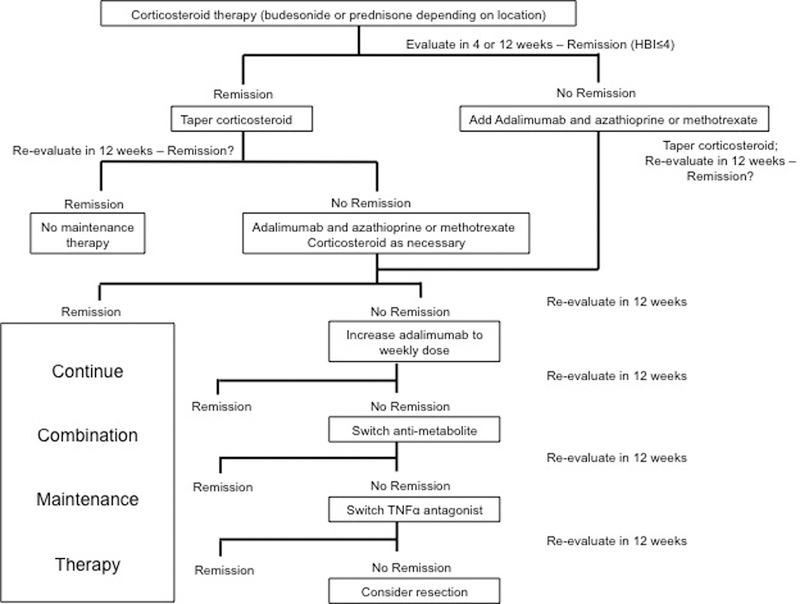

Intervention vs. Comparator

In the early combined immunosuppression treatment strategy arm, specific education on the treatment algorithm was provided to the practices (Figure 1). In these practices, patients with failure to achieve clinical remission (defined as Harvey Bradshaw Index score ≤4) after initiation of corticosteroids (4 weeks in Canada, 12 weeks in Belgium) received combination therapy with a tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) antagonist and anti-metabolite (thiopurines or methotrexate). Disease activity was reassessed at 12-week intervals, and patients with persistently active disease (Harvey Bradshaw Index score>6) were sequentially escalated in a stepwise algorithm (escalation of TNFα antagonist, switching anti-metabolite, switching TNFα antagonist and finally surgery) until clinical remission was achieved.

Figure 1.

Early Combined Immunosuppression algorithm in REACT

Practitioners assigned to conventional management were unaware of the early combined immunosuppression-algorithm details and managed patients according to usual practice. Patients at conventional management sites were treated according to the usual practice of their physicians.

Outcomes

For this study, primary effectiveness outcomes were achieving corticosteroid-free clinical remission by 24 months and time to composite major adverse outcome of Crohn’s disease-related surgery, hospitalization or development of serious complications (abscess, fistula, stricture, serious worsening of disease activity, extra-intestinal manifestations or serious drug-related complications). Secondary effectiveness outcomes were individual components of the composite outcome – time to disease-related hospitalization, surgery, disease-related complications (abscess, fistula, stricture), serious worsening of Crohn’s disease activity (increased bowel frequency, abdominal pain, or rectal bleeding reported by the site investigator that required a treatment intervention) and extra-intestinal manifestations. Safety outcomes of interest were drug-related adverse outcomes and mortality.

Statistical Analysis

For dichotomous outcomes we used modified Poisson model for correlated binary data.15 For time-to-event endpoints, we used marginal Cox proportional hazards models in which adjustment was made for practice size and country and for the effect of clustering by practice. To assess potential confounders, the association between demographic and baseline characteristics (sex, smoking status, disease duration, disease location, fistula involvement, previous surgery for Crohn’s disease, Harvey Bradshaw Index, corticosteroid use, antimetabolite, use, TNFα antagonist use, combination antimetabolite and TNFα antagonist use, and quality of life indices including Short Form-36 version 2.0 [SF-36] and European Quality of Life Index Version 3L [EQ5D]) and outcomes was examined. Those univariable associations found to be significantly at the 0.10 level were then forced into the model. Characteristics were then removed in a stepwise manner, retaining those characteristics that were significant at the 0.10 level. For each outcome, we compared whether the magnitude of effect of intervention (early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management) was different between younger and older patients with Crohn’s disease, via the interaction between age group and treatment group in each model, adjusting for those baseline characteristics retained in the backward elimination process. Since the original trial was not specifically designed to answer the question of whether age modify the effect of early combined immunosuppression in patients with Crohn’s disease, these results should be considered exploratory. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of participants by age, and treatment strategy assignment. As compared to younger patients, older patients had longer disease duration (15.6y vs. 9.8y, p<0.01), more likely to have had undergone prior Crohn’s disease-related surgery (55.3% vs. 45.6%, p<0.01), less likely to have active fistula at baseline (3.9% vs. 7.9%, p=0.01) and were less likely to have been on TNFα antagonist monotherapy at baseline (12.5% vs. 22.2%, p<0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients by age at time of trial entry, and by treatment strategy assignment

| Age <60y | Age ≥60y | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Management (n=760) |

Early combined immunosuppr ession (n=910) |

Conventional Management (n=138) |

Early combined immunosuppr ession (n=173) |

||

| Male, n (%) | 324 (42.6%) | 384 (42.2%) | 58 (42.0%) | 72 (41.6%) | |

|

Disease Duration (in months), mean |

143.7 | 138.3 | 219.0 | 213.4 | |

| Current Smoker, n (%) | 142 (18.7%) | 235 (25.9%) | 21 (15.2%) | 36 (20.8%) | |

| Medications | |||||

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 126 (16.6%) | 177 (19.5%) | 28 (20.3%) | 29 (16.8%) | |

| Antimetabolites, n (%)* | 213 (28.0%) | 299 (32.9%) | 38 (27.5%) | 61 (35.3%) | |

| TNFα-Antagonists, n (%)* | 175 (23.0%) | 196 (21.5%) | 21 (15.2%) | 18 (10.4%) | |

| Combination therapy, n (%) | 101 (13.3%) | 115 (12.6%) | 15 (10.9%) | 13 (7.5%) | |

| Previous surgery for CD, n (%) | 354 (46.6%) | 407 (44.8%) | 77 (55.8%) | 95 (54.9%) | |

| Disease Location | |||||

| Colon, n (%) | 151 (19.9%) | 207 (23.0%) | 27 (19.7%) | 50 (29.1%) | |

| Small bowel, n (%) | 263 (34.7%) | 281 (31.2%) | 56 (40.9%) | 61 (35.5%) | |

| Both, n (%) | 344 (45.4%) | 413 (45.8%) | 54 (39.4%) | 61 (35.5%) | |

| Fistula, active, n (%) | 67 (8.8%) | 65 (7.2%) | 4 (2.9%) | 8 (4.7%) | |

| Steroid-free clinical remission | 395 (53.6%) | 499 (56.4%) | 77 (59.2%) | 99 (58.2%) | |

Antimetabolites and TNF-Antagonists are reported here as not in combination with one another, that is, if on both TNF-antagonists and antimetabolites, they will not be included in the number & percentage of subjects on antimetabolites but will be included with those on combination therapy Steroid-free clinical remission was defined as Harvey Bradshaw Index ≤4 while being steroid-free.

Outcomes

Effectiveness outcomes:

Table 2 shows the magnitude of effect of intervention (early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management) between younger and older patients, after adjustment for baseline characteristics noted to be related to each outcome. No significant difference was observed between younger and older patients in the risk of achieving corticosteroid-free clinical remission (<60y: RR, 1.06 [0.98–1.15] vs. ≥60y: RR 1.09 [0.90–1.33], p-interaction=0.78) with early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management with estimates favoring early combined immunosuppression, as per the original trial result in all patients at 24 months. Similarly, there was no significant difference in the magnitude of benefit with early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management in younger vs. older patients on time to occurrence of composite major adverse outcome (<60y: HR, 0.71 [0.53–0.96] vs. ≥60y: HR, 0.69 [0.31–1.51], p-interaction=0.92) (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the magnitude of benefit with early combined immunosuppression for time to serious disease-related complications or time to worsening of Crohn’s disease activity.

Table 2.

Effect of age, adjusted for associated baseline factors, on magnitude of benefit with early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management in patients with Crohn’s disease

| Estimate (95% CI) Early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Age <60 | Age ≥60 | p-value for age & treatment group Interaction |

|

|

Corticosteroid-free clinical remission* |

1.06 (0.98, 1.15) | 1.09 (0.90, 1.33) | 0.78 | |

|

Time to composite major adverse outcome (CD-related surgery, hospitalization, serious complications) |

0.71 (0.53, 0.96) | 0.69 (0.31, 1.51) | 0.92 | |

| CD-related surgery | 0.68 (0.46, 1.01) | 0.90 (0.34, 2.42) | 0.60 | |

| CD-related hospitalization | 0.83 (0.66, 1.05) | 0.79 (0.36, 1.77) | 0.91 | |

| Serious complications§ | 0.74 (0.53, 1.03) | 0.68 (0.29, 1.56) | 0.83 | |

|

Time to disease-related complications⌃ |

0.80 (0.59, 1.08) | 0.52 (0.22, 1.21) | 0.33 | |

| Time to worsening CD¶ | 0.87 (0.48, 1.59) | 0.66 (0.16, 2.71) | 0.69 | |

For corticosteroid-free clinical remission outcome, estimate was risk ratio derived from modified Poisson model; for all other outcomes, estimate was hazard ratio derived from Cox proportional hazard analysis

Serious complications were defined as development of new fistula, abscess, stricture, serious worsening of Crohn’s disease activity, or extra-intestinal manifestations

Disease related complications included new fistula, abscess or stricture

Serious worsening of Crohn’s disease was defined as increased bowel frequency, abdominal pain, or rectal bleeding reported by the site investigator that required a treatment intervention

Safety outcomes:

Mortality was higher in older patients (14/311, 4.5%) as compared to younger patients (3/1670, 0.2%), although more deaths were observed in the older group on conventional management compared to early combined immunosuppression. Details of deaths in both groups are shown in eTable 1. Cardiopulmonary (8 patients), malignancy (5 patients) and sepsis (2 patients) were leading causes of death.

DISCUSSION

In this post-hoc analysis of the REACT trial comparing the magnitude of benefit with an algorithmic early combined immunosuppression strategy vs. conventional management, we found no difference in older versus younger patients in maintaining corticosteroid-free clinical remission and delaying risk of Crohn’s disease-related surgery, hospitalization and/or serious complications. As anticipated, a greater percentage of deaths occurred in older patients died, but the percentage was not higher in patients in the early combined immunosuppression group compared to the conventional management group in the two age groups. In the absence of clinical trials specifically focusing on older patients and clear evidence-based guidance, these data provide useful information on the safety and efficacy of a strategy of algorithmic early combined immunosuppression compared to conventional management in older patients with Crohn’s disease.

There are considerable challenges in the management of older patients with IBD. Besides intrinsic differences in disease phenotype and behavior, particularly those with older disease onset, there are systematic differences in risks of disease- and treatment-complications, and extra-intestinal complications (e.g., cardiovascular disease, malignancy) between older and younger patients.16, 17 This may be attributed to immunosenescence, diminished physical reserve, multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy frequently seen in this patient population. In a nationally representative cohort study, Nguyen and colleagues observed that older patients with IBD have higher annual burden and costs associated with hospitalization, as compared to younger patients, with higher rates of hospitalization attributed to serious infections and cardiovascular diseases.8 This leads to difficulty in estimating risk-benefit trade-offs of chronic immunosuppressive therapy in older patients, and has resulted in greater use of long-term corticosteroids and lower use of corticosteroid sparing therapies.10, 11 The results of this post-hoc analysis challenge the notion of ‘undertreating’ older patients to avoid treatment complications by demonstrating that a strategy of algorithmic early combined immunosuppression may also be effective and safe in older patients with IBD, potentially decreasing corticosteroid use and risk of Crohn’s disease-related complications. The benefit of a strategy of treating with TNFα-based therapy over chronic corticosteroids was also demonstrated in a retrospective matched cohort study among Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries.18 In their study, Lewis and colleagues observed that TNFα antagonist-based therapy in Crohn’s disease was associated with lower risk of death, major adverse cardiovascular outcomes and pathologic fractures as compared to chronic corticosteroid therapy, without any difference in risk of serious infections. This benefit was seen in both older and younger patients.

A major concern with use of combined immunosuppression in older adults is the risk of serious infections. However, it is important to recognize that besides advanced age and immunosuppressive therapy, most consistent disease-related factors associated with serious infections in patients with IBD include severe disease activity, exposure to corticosteroids and narcotics.19–21 Underlying severely active disease may increase risk of serious infections through impaired immune surveillance, increased risk of abdominal infections (for example, intra-abdominal or perianal abscesses in patients with penetrating Crohn’s disease), or through need for repeated courses of corticosteroids to temporarily improve inflammation-driven symptoms. In our study, a strategy of early combined immunosuppression was not found to be differentially effective in younger than older patients with Crohn’s disease in terms of decreasing risk of serious disease-related complications and hospitalization.

There are several strengths of our study. This was a post-hoc analysis of a prospective pragmatic cluster-randomized trial of community gastroenterologists, and hence the findings would be broadly applicable. With a two-year follow-up, we were able to ascertain clinically important outcomes including risk of disease-related complications, surgery and hospitalization. However, there are important limitations to our analysis. First, the trial was not designed or powered to compare the effectiveness of early combined immunosuppression vs. conventional management between older and younger adults and, hence, the results should be considered exploratory and interpreted with caution. Second, since this was a community practice-level pragmatic trial of treatment strategies (not of specific medications), detailed assessment and attribution of all treatment-emergent and treatment-related adverse events was not performed, possibly resulting in a low observed rate of serious drug-related complications. With a potentially lower event rate and follow-up restricted to a maximum of 24 months, treatment-related harm could not be adequately assessed in this analysis. Third, while this was one of the largest clinical trials of IBD with a 2-year follow-up, long-term comparative effectiveness and safety of these strategies remains to be seen. Fourth, our study does not adequately inform on the treatment targets – clinical remission vs. endoscopic remission – in older patients. Recognizing suboptimal correlation between clinical and endoscopic disease activity in patients with Crohn’s disease, algorithmic treatment step up based on clinical disease activity alone may lead to overtreatment of some patients who otherwise have no objective evidence of inflammation. The ongoing follow-up REACT-2 trial will inform impact of treating to a target of mucosal healing. Finally, in this trial, treatment steps focused on TNFα antagonist-based therapy. With the availability of several non-TNFα-based biologic therapies and ongoing trials of targeted small molecules with varying efficacy and safety profiles, risk-benefit trade-offs of algorithmic early treatment step up in older patients using non-TNF therapy may be different.

In conclusion, based on a post-hoc analysis of the REACT trial, we have demonstrated that, there is no evidence that a treatment strategy of early combined immunosuppression based on TNFα antagonist is any less effective in older adults than younger adults with Crohn’s disease. Whilst more deaths were observed in older patients, there was a similar proportion in patients in both the early combined immunosuppression and conventional management groups. In selected older patients with suboptimal disease control, an algorithmic treatment step-up strategy may be considered, to decrease treatment disutility and avoid persistence on chronic corticosteroids. Future studies focusing on older patients at higher risk of disease complications and designed to evaluate optimally tailored treatment approaches and treatment targets and to evaluate the impact of non-TNFα biologics and targeted small molecules are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the entire team of the REACT clinical trial without whose efforts this study would not have been feasible

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award #144271, Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award #404614, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K23DK117058 to Siddharth Singh. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- No other financial support was received for this project

Clinical Trial Identifier: NCT01030809

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Siddharth Singh: Research support from Pfizer and AbbVie, consulting fees from AbbVie and Takeda, outside the submitted work

Larry Stitt: None

Reena Khanna: Fees for Consulting/Speaking from: AbbVie, Encycle, Janssen, Pendopharm, Pfizer, Robarts Clinical Trials, Shire, and Takeda Canada outside the submitted work

Parambir Dulai: Research support from Pfizer, and has received research support, travel support and served as a consultant for Takeda outside the submitted work

Guangyong Zou: None

William Sandborn: Research grants from Atlantic Healthcare Limited, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, Lilly, Celgene/Receptos; consulting fees from Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Conatus, Cosmo, Escalier Biosciences, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead, Gossamer Bio, Janssen, Lilly, Miraca Life Sciences, Nivalis Therapeutics, Novartis Nutrition Science Partners, Oppilan Pharma, Otsuka, Paul Hastings, Pfizer, Precision IBD, Progenity, Prometheus Laboratories, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Robarts Clinical Trials (owned by Health Academic Research Trust or HART), Salix, Shire, Seres Therapeutics, Sigmoid Biotechnologies, Takeda, Tigenix, Tillotts Pharma, UCB Pharma, Vivelix; and stock options from Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Oppilan Pharma, Escalier Biosciences, Gossamer Bio, Precision IBD, Progenity

Brian Feagan: Received grant/research support from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Tillotts Pharma AG, AbbVie, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Centocor Inc., Elan/Biogen, UCB Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, ActoGenix, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.; consulting fees from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Centocor Inc., Elan/Biogen, Janssen-Ortho, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, UCB Pharma, AbbVie, Astra Zeneca, Serono, Genentech, Tillotts Pharma AG, Unity Pharmaceuticals, Albireo Pharma, Given Imaging Inc., Salix Pharmaceuticals, Novonordisk, GSK, Actogenix, Prometheus Therapeutics and Diagnostics, Athersys, Axcan, Gilead, Pfizer, Shire, Wyeth, Zealand Pharma, Zyngenia, GiCare Pharma Inc., and Sigmoid Pharma; and speakers bureaux fees from UCB, AbbVie, and J&J/Janssen

Vipul Jairath: Consulting fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Arena pharmaceuticals, Genetech, Pendopharm, Sandoz, Merck, Takeda, Janssen, Robarts Clinical Trials, Topivert, Celltrion; speaker’s fees from Takeda, Janssen, Shire, Ferring, Abbvie, Pfizer

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and Preventing the Global Increase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152(2):313–321 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ananthakrishnan AN, Donaldson T, Lasch K, Yajnik V. Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Elderly Patient: Challenges and Opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, Wheaton AG, Croft JB. Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among Adults Aged >/=18 Years - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(42):1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charpentier C, Salleron J, Savoye G, et al. Natural history of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Gut 2014;63(3):423–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heresbach D, Alexandre JL, Bretagne JF, et al. Crohn’s disease in the over-60 age group: a population based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16(7):657–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ananthakrishnan AN, Shi HY, Tang W, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: Phenotype and Clinical Outcomes of Older-onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10(10):1224–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39(5):459–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen NH, Ohno-Machado L, Sandborn WJ, Singh S. Infections and Cardiovascular Complications are Common Causes for Hospitalization in Older Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24(4):916–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benchimol EI, Cook SF, Erichsen R, et al. International variation in medication prescription rates among elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7(11):878–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Govani SM, Wiitala WL, Stidham RW, et al. Age Disparities in the Use of Steroid-sparing Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22(8):1923–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waljee AK, Wiitala WL, Govani S, et al. Corticosteroid Use and Complications in a US Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort. PLoS One 2016;11(6):e0158017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terdiman JP, Gruss CB, Heidelbaugh JJ, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the use of thiopurines, methotrexate, and anti-TNF-alpha biologic drugs for the induction and maintenance of remission in inflammatory Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2013;145(6):1459–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna R, Bressler B, Levesque BG, et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn’s disease (REACT): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386(10006):1825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahan BC, Cro S, Dore CJ, et al. Reducing bias in open-label trials where blinded outcome assessment is not feasible: strategies from two randomised trials. Trials 2014;15:456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou GY, Donner A. Extension of the modified Poisson regression model to prospective studies with correlated binary data. Stat Methods Med Res 2013;22(6):661–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz S, Pardi DS. Inflammatory bowel disease of the elderly: frequently asked questions (FAQs). Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106(11):1889–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ha CY, Katz S. Clinical implications of ageing for the management of IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;11(2):128–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis JD, Scott FI, Brensinger CM, et al. Increased Mortality Rates With Prolonged Corticosteroid Therapy When Compared With Antitumor Necrosis Factor-alpha-Directed Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113(3):405–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brassard P, Bitton A, Suissa A, Sinyavskaya L, Patenaude V, Suissa S. Oral corticosteroids and the risk of serious infections in patients with elderly-onset inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109(11):1795–802; quiz 1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT registry. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107(9):1409–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osterman MT, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, et al. Crohn’s Disease Activity and Concomitant Immunosuppressants Affect the Risk of Serious and Opportunistic Infections in Patients Treated With Adalimumab. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111(12):1806–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.