Abstract

Background:

Intentional injury, including suicide and assault, is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. We aimed to determine whether immigrant and nonimmigrant women differ in their 1-year risk of intentional injury after birth.

Methods:

This population-based retrospective cohort study used administrative data from Ontario from 2002 to 2012. Risk of self-inflicted injury (self-harm or suicide), and injury inflicted by others (assault or homicide), were each analyzed within 1 year after delivery of a live-born infant for immigrant and nonimmigrant mothers. Relative risks (RRs) were adjusted for maternal age, parity, income, resource utilization and psychiatric history.

Results:

The study included 327 279 immigrant and 942 502 nonimmigrant mothers. Risk of self-inflicted injury was similar among immigrants and nonimmigrants (adjusted RR 0.91, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.78–1.04), with no variation by duration of residence or refugee status. Immigrants were at lower risk than nonimmigrants for injury inflicted by others (adjusted RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.51–0.64); that risk was higher among refugees than among nonrefugee immigrants (adjusted RR 1.79, 95% CI 1.33–2.41), and it was higher among long-term (adjusted RR 2.27, 95% CI 1.76–2.91) and medium-term (adjusted RR 1.58, 95% CI 1.19–2.11) immigrants than among recent immigrants. Variability by country of origin was observed for both injury types.

Interpretation:

Immigrant mothers have a reported risk for self-inflicted injury after birth similar to that of their Canadian-born counterparts. The extent to which selective underreporting of intentional injury in immigrant women might explain our findings is a key consideration for future research.

Intentional injury, including suicide and assault, is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality for postpartum women, with potential for devastating consequences for women, children and families.1 Suicidal thoughts are common among women after they give birth, affecting as many as 9% of women,2 and suicide accounts for a high proportion of maternal deaths globally.1,3,4 Assault, mainly by intimate partners, affects up to about 13% of women perinatally5 and is also responsible for some maternal mortality.6–9

Immigrant women contribute one-quarter to one-third of births in high-income countries,10 but their risk for intentional injury in the postnatal period is unknown. The selective nature of the immigration process can result in an overrepresentation of relatively young, healthy, educated and economically active people — the so-called “healthy immigrant effect.”11–13 However, some immigrant women exhibit up to 3 times the rate of postpartum depression of their nonimmigrant counterparts, a risk factor for suicidal thoughts and actions.14–16 Outside the perinatal period, women from certain immigrant groups are at higher risk for intimate partner violence and homicide than nonimmigrants.17,18 Given the large number of births to immigrant women in many countries, specific knowledge about if, and how, immigration status is a risk factor for intentional injury in the postpartum period may be important to the design and delivery of policies and interventions to prevent this serious outcome.

We aimed to determine whether immigrant women have a different risk of intentional injury in the first year after giving birth than nonimmigrant mothers. Within a large population-based Canadian sample, we compared the risk for each of self-inflicted injury (self-harm or suicide) and injury inflicted by others (assault or homicide) between immigrant and nonimmigrant women in the 1 year following delivery of a live-born infant. Risk was also evaluated among immigrants by immigration characteristics of refugee status, duration of residence and country of origin.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective population-based cohort study was completed in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, which has about 13.5 million people. Included were all Ontario women who had a live birth between Apr. 1, 2002, and Mar. 31, 2012. Outcomes were assessed up to 1 year after the index birth.

Data sources

Deidentified and linked sociodemographic and health administrative databases were accessed through ICES in Toronto, Ontario (www.ices.on.ca). The MOMBABY data set, derived from the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (CIHI-DAD), was used to identify all in-hospital deliveries (> 98% of all births)19; a variable in this data set records parity at the time of each live birth. The Ontario segment of the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) database contains detailed information for immigrants to the province from 1985 onward, including their refugee status, date of immigration and country of origin. About 86% of IRCC records are successfully linked to ICES data by probabilistic matching.20 The National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS) contains diagnostic information for all emergency department visits, including for intentional injuries, and the Ontario Vital Statistics Database records cause of death. The Registered Persons Database includes information about sex, age and postal code for all Ontario residents. The Ontario Health Insurance Plan contains physician billings, including diagnostic and procedure codes. The Ontario Mental Health Reporting System contains psychiatric hospital admission data. These linked data sets contain complete and reliable data, highly valid for primary diagnoses in acute health care encounters.21–23

Participants

We considered all Ontario women aged 10–50 years who had a live-born infant and who had a valid health card number. Women entered the cohort at each birth, unless a birth was within 1 year of a previous one. Women were classified as immigrant or nonimmigrant, on the basis of their inclusion in the Ontario segment of the IRCC data set. For additional analyses, immigrant women were further classified as refugee or nonrefugee, by duration of residence in Canada at the time of the index birth (≥ 10 yr, 5–9 yr or < 5 yr), and by country of origin.

Outcomes

We assessed 2 main study outcomes within 365 days after the index birth. The first was self-inflicted injury, a composite that included any form of self-harm or death by suicide. The second was injury inflicted by others, a composite that included maternal assault or death. The NACRS data set was used to identify International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10), codes for self-harm with deliberate (X60–X84) and undetermined (Y10–Y19, Y28) intent. The latter codes were included because they are strongly associated with future deliberate self-harm.24 Injury inflicted by others was identified using ICD-10 codes (X85–Y09, Y87.1), following the proposed framework for presenting injury data recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Canadian ICD-10-CA coding standards.25,26 Within the ICD-10-CA framework, external cause of injury codes (including X and Y codes) are mandatorily required for use with a code from S00 to T98, so T74 codes that cover adult abuse or other maltreatment were not extracted separately.26 A US validation study had 95% agreement between clinical charts and International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9), classification with a similar approach.27 Deaths by suicide were identified in the Ontario Vital Statistics Database; homicides were a death from external injury where there was also a documented assault in the NACRS data set.28

Covariates

Covariates included maternal age, parity and neighbourhood income level, each at the index birth. In the 2 years before the index birth, we assessed for maternal psychiatric diagnoses (i.e., psychotic disorders, mood disorders, substance and alcohol use disorders) and maternal medical morbidity, summarized using health care resource utilization bands, where categories 4 and 5 represent patients with high and very high care needs as per the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups Case-Mix System.29

Statistical analysis

We compared the risk for each of the 2 main study outcomes between immigrant and nonimmigrant women, using modified Poisson regression with robust error variance, to account for potential clustering of more than 1 birth within an individual woman. Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were generated. Models were adjusted for variables chosen, a priori, to be important potential confounders: maternal age, parity, residential income quintile, medical morbidity (defined by resource utilization band quintile) and prior maternal psychiatric diagnosis.

In analyses restricted to immigrant women, the risk for the 2 main study outcomes was assessed by refugee versus nonrefugee status, by duration of residence in Canada at the time of in the index birth (≥ 10 yr, 5–9 yr or < 5 yr) and by country of origin. For maternal country of origin, the top-20 immigrant countries contributing the most births in Ontario were chosen, with women from India serving as the reference group, because they were the most numerous. Relative risks were adjusted for age, parity and other immigration characteristics.

Because of small sample sizes, modified Poisson regression models did not always converge. In that situation, Cox proportional hazard models were used, accounting for clustering and generating hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs. The analysis of the individual elements of the main study outcomes could not be reported because of the low outcome rates for injuries that resulted in death.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 for Unix (SAS version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc.). Cell sizes less than 6 were not reportable because of Ontario privacy regulations.

Ethics approval

The study received research ethics board approval from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Ontario (no. 2016 0904 337 000).

Results

There were 1 269 781 live births among 327 279 immigrants and 942 502 nonimmigrants in Ontario between Apr. 1, 2002, and Mar. 31, 2012. Among the immigrant women, 41 500 (12.7%) were refugees, and close to half (n = 147 286; 45.0%) had lived in Canada less than 5 years. Immigrant women were most frequently from India, China, Pakistan and the Philippines (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/2/E227/suppl/DC1). They were similar in age to nonimmigrants but more likely to be multiparous (56.9% v. 53.7%) and to reside in a low-income neighbourhood (34.4% v. 18.6%) (Table 1). Immigrant women had slightly higher rates of diabetes (2.0% v. 1.7%) and were more likely to be in the highest resource utilization band for general medical services. However, they had lower rates of maternal psychiatric diagnoses in the 2 years before delivery. Clinically, perinatal outcomes appeared not to differ substantively by immigrant status.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of immigrant and nonimmigrant women who gave birth in Ontario during the study period

| Characteristic | No. (%) of women* | |

|---|---|---|

| Immigrants n = 327 279 |

Nonimmigrants n = 942 502 |

|

| Demographic | ||

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 30.5 ± 5.2 | 29.7 ± 5.6 |

| Primiparous | 141 131 (43.1) | 435 940 (46.3) |

| Lowest neighbourhood income quintile | 112 624 (34.4) | 175 588 (18.6) |

| Maternal morbidity within 2 yr before the index birth | ||

| Diabetes mellitus before or in pregnancy | 6445 (2.0) | 16 057 (1.7) |

| Hypertension before or in pregnancy | 6276 (1.9) | 26 657 (2.8) |

| Health care resource utilization bands 4 and 5 (highest) | 233 840 (71.4) | 638 345 (67.7) |

| Psychiatric morbidity within 2 yr before the index birth | ||

| Mood disorder | 7372 (2.3) | 46 849 (5.0) |

| Psychotic disorder | 680 (0.2) | 2929 (0.3) |

| Substance or alcohol use disorder | 1613 (0.5) | 24 966 (2.6) |

| Primary care physician visit for a psychiatric disorder | 75 978 (23.2) | 271 515 (28.8) |

| Psychiatrist visit | 5518 (1.7) | 34 413 (3.7) |

| Psychiatric hospital admission | 532 (0.2) | 4358 (0.5) |

| Deliberate self-harm | 2588 (0.8) | 20 396 (2.2) |

| Obstetrical and perinatal indicators at the index birth | ||

| Preterm birth < 37 wk gestation | 21 594 (6.6) | 68 637 (7.3) |

| Birth weight, mean ± SD, g | 3282 ± 557 | 3410 ± 584 |

| Cesarean delivery | 92 094 (28.1) | 258 841 (27.5) |

| Neonatal morbidity | ||

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 3724 (1.1) | 14 216 (1.5) |

| Seizure | 949 (0.3) | 3583 (0.4) |

| Sepsis | 4144 (1.3) | 14 094 (1.5) |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 1745 (0.5) | 5490 (0.6) |

| Persistent fetal circulation | 893 (0.3) | 3172 (0.3) |

| Congenital/neonatal infection | 1219 (0.4) | 1219 (0.4) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 45 976 (14.0) | 121 434 (12.9) |

| Infant mortality < 365 d of the index birth, no. (rate) | 1227 (3.8 per 1000) | 3276 (3.5 per 1000) |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Unless specified otherwise.

In the 1-year period after the index birth, 4424 births were affected by intentional injury inflicted either by self or others — a rate of 3.48 per 1000 births. There were 1411 nonfatal self-inflicted injury events (1.11 per 1000 births), 3061 nonfatal injuries inflicted by others (2.41 per 1000) and 44 deaths due to injury following self-inflicted injury or an injury inflicted by others (0.03 per 1000 births).

In the unadjusted comparison, immigrants had a lower rate of fatal or nonfatal self-inflicted injury (0.73 per 1000) than nonimmigrants (1.27 per 1000); the crude RR was 0.58 (95% CI 0.50–0.67) (Table 2). The relation was attenuated after we adjusted for other covariates in the multivariable model (adjusted RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.78–1.04), mainly because of the higher burden of prepregnancy mental illness in nonimmigrant women (Table 2). Immigrants had a lower associated risk of injury inflicted by others (1.10 per 1000 deliveries) than nonimmigrants (2.88 per 1000); the crude RR was 0.38 (95% CI 0.34–0.43) and the adjusted RR was 0.57 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.64) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Risk of self-inflicted injury (self-harm or suicide) and injury inflicted by others (assault or homicide), comparing 327 279 immigrant women and 942 502 nonimmigrant women who gave birth in Ontario during the study period

| Variable | Self-inflicted injury | Injury inflicted by others | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| No. with the outcome (rate per 1000 births) | Crude RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR* (95% CI) | No. with the outcome (rate per 1000 births) | Crude RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR* (95% CI) | |

| Nonimmigrant status | 1199 (1.27) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 2710 (2.88) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

|

| ||||||

| Immigrant status | 240 (0.73) | 0.58 (0.50–0.67) | 0.91 (0.78–1.04) | 360 (1.10) | 0.38 (0.34–0.43) | 0.57 (0.51–0.64) |

|

| ||||||

| Maternal age, yr | 0.86 (0.85–0.87) | 0.81 (0.80–0.81) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| No. of previous births | 1.44 (1.39–1.51) | 1.64 (1.59–1.68) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Maternal income quintile | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 1, 2 or 3 (lower) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 4 or 5 (higher) | 0.86 (0.76–0.98) | 0.61 (0.56–0.68) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Resource utilization band | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 1, 2 or 3 (lower) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 4 or 5 (higher) | 0.88 (0.79–0.98) | 1.04 (0.96–1.12) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Prior maternal psychiatric diagnosis | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 7.01 (6.25–7.86) | 3.55 (3.26–3.86) | ||||

Note: CI = confidence interval, RR = relative risk.

Adjusted for maternal age, parity, income quintile, resource utilization band and prior maternal psychiatric diagnosis.

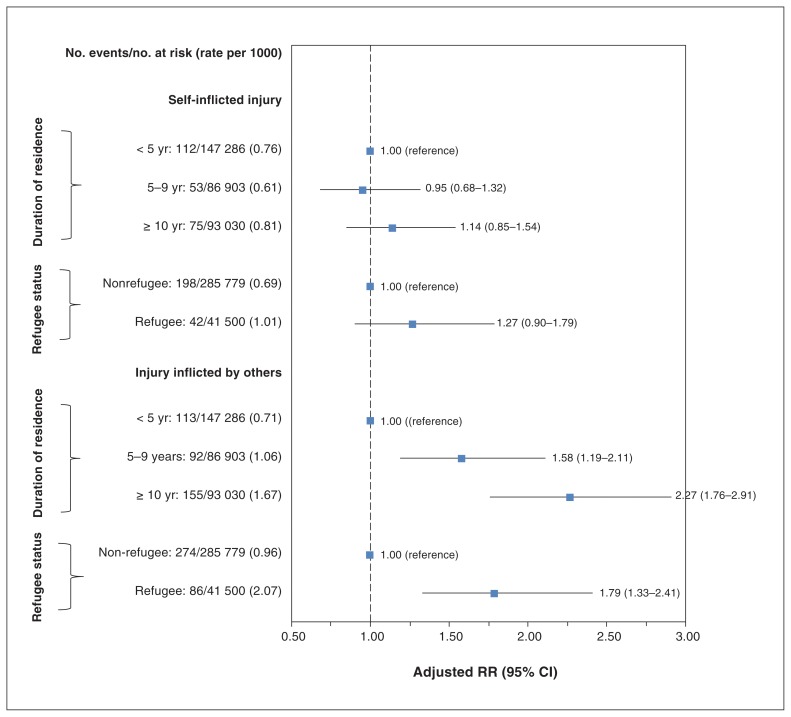

When we restricted the analysis to immigrant women, the RRs for self-inflicted injury were similar by duration of residence in Canada and by refugee status (Figure 1). Self-inflicted injury was notably less common among immigrant women from China, Jamaica and the Former Republic of Yugoslavia, compared with immigrant women from India, the largest immigrant group by population size (Figure 2A, Appendix 1).

Figure 1:

Risk of self-inflicted injury (self-harm or suicide) and injury inflicted by others (assault or homicide), by duration of residence and by refugee status, restricted to immigrants to Canada. Note: Relative risks (RRs) are adjusted for maternal age and parity. CI = confidence interval.

Figure 2:

Risks of (A) self-inflicted injury (self-harm or suicide) and (B) injury inflicted by others (assault or homicide) among immigrant women, comparing those from 19 different countries to women from India. Note: Hazard ratios (HRs) are adjusted for maternal age, parity, duration of residence and refugee status. CI = confidence interval.

Risk for injury inflicted by others increased with longer duration of residence in Canada (Figure 1). For example, the corresponding rate among immigrant women living in Canada for 10 or more years was 1.67 per 1000 births, compared with a rate of 0.77 per 1000 among immigrant women living in Canada for less than 5 years (Figure 1). Refugees (2.07 per 1000) were at a higher risk than nonrefugee immigrants (0.96 per 1000) (Figure 1). Women from Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Jamaica and Somalia were at the highest risk for injury inflicted by others (Figure 2B, Appendix 1).

Interpretation

Intentional injury to mothers in the first year after pregnancy was observed for almost 1 in every 250 births in Canada. The risk for self-inflicted injury was similar among immigrants and nonimmigrants, after considering differences in preexisting psychiatric morbidity. Although injury inflicted by others was less likely to occur among immigrant women, certain subgroups were at higher risk than others, with rates closer to that of Canadian-born women.

The overall rate of self-inflicted injury in this study was similar to rates reported previously in high-income countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom but no previous studies on self-inflicted injury in immigrant women were identified for comparison.4,30,31 Since immigrant women have high rates of postpartum depression, a major risk factor for suicidality, the reason why the risk for this outcome was not elevated in immigrant women is unclear.15,32,33 The causes of severe postpartum mental illness (i.e., illness that might result in suicidality) may be mediated more by biological (i.e., genetic sensitivity to rapid hormonal shifts) than socioenvironmental stressors.34 Hence, higher stress related to immigrant status could increase the risk for mental illness generally, but not for a severe outcome like self-injury. Members of our team previously observed a similar phenomenon for postpartum psychiatric hospital admission, with comparable rates between immigrant and nonimmigrant mothers.35 That being said, attention to the issue of self-injury in immigrant mothers may still require specific attention, even if these women are not at higher than average risk. Symptoms of mental illness may present differently in women from different cultures. For example, women from some Asian countries may present with somatic symptoms such as nonspecific pain or discomfort as an initial sign,36 so mental illness might be missed in them.

Our results for injury inflicted by others are consistent with those of a Canadian survey in which rates of self-reported intimate partner violence were about 50% lower in immigrant mothers.37 Given that we observed increasing risk by duration of residence, our findings could be partly explained by a healthy immigrant effect in which people exhibit greater health at their arrival and then take on negative health attributes of their host country over time, partly in response to the stress of acculturation and norms of the new country.12 Alternatively, the observed lower rate of intentional injury inflicted by others may have been a result of selective underidentification. Especially for those newest to the country, issues such as social stigma, language fluency, fear of deportation or reprisal, or the presence of a male relative at a health visit might discourage a woman who recently immigrated from disclosing that a specific injury was intentional.38,39 Health care providers with minimal knowledge of a woman’s cultural norms may underidentify intentional injury in some cases.40

Interestingly, our finding that immigrant mothers were at lower risk for injury inflicted by others is not consistent with prior European data that showed a higher homicide rate among female migrants.17,18,41 These prior studies were not restricted to events arising in the postpartum period, nor did they include data on nonfatal assaults. Thus, the extent to which our findings reflect a Canadian phenomenon or are generalizable to other countries is unclear. In our study, higher rates of assault — approaching those among nonimmigrant women — were observed among some immigrant groups, namely refugees and women from certain countries of origin. This is consistent with studies that observed a higher risk of sexual assault among mothers who are refugees and asylum seekers than among nonrefugee immigrant mothers.42 World regions with high rates of perinatal intimate partner violence do include areas of Africa and the Caribbean where the higher rates of immigrant assault were observed.43–45 The extent to which our findings are generalizable to other countries or jurisdictions may depend to some extent on differences in immigrant characteristics in those regions.

Limitations

Limitations inherent to the use of these administrative data sets include the inability to measure key covariates such as marital status or paternal history that could help explain the findings. Further, administrative data can only capture those injuries severe enough to warrant declaration, such as an emergency department encounter. For self-inflicted injury, there is no mechanism to distinguish between injuries where a woman intended to die versus self-harm, such as for self-regulation or a plea for help. Immigrant women, and particularly newer immigrant women, may be less comfortable presenting to an emergency department, especially when their injuries are not life threatening, for reasons similar to those discussed above, which could lead to selective under-disclosure. This could result in selective undercounting of intentional injury in some immigrant groups. Finally, the results should be interpreted with the following additional limitations in mind. Data on immigration status were unavailable before 1985, so women who had immigrated to Canada before that time (i.e. 17 yr before the first birth in the cohort) would have been classified into the nonimmigrant group. Women who gave birth again within 1 year of the index birth were not included in the sample so the results cannot be generalized to them. We might have underestimated the prevalence of preexisting mental illness in recent immigrant women for whom data on history before immigration to Canada were unavailable. Also, the small number of outcomes limits the precision of the estimates.

Conclusion

This study expands knowledge about risk factors for postpartum self-inflicted injury and injury perpetrated by others. Immigrant and nonimmigrant women appear to be at similar risk for intentional self-injury. Symptoms of mental illness may present differently in women from different cultures. Awareness of cultural differences can help health care providers to rapidly identify emerging mental illness and ensure women are screened for any ensuing suicidality. Although the lower rates of reported assault among immigrant women are somewhat reassuring, a key avenue for future research is to determine whether intentional injury is underidentified in this population. In the meantime, the observed vulnerability of refugee women and immigrants from specific countries supports the rationale to enhance the cultural competence and awareness of health care providers who care for women during pregnancy and in the months thereafter.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: Sophie Grigoriadis reports royalties from Psychotherapy Essentials To Go, UpToDate and the Compendium of Therapeutic Choices outside the submitted work and personal fees from Allergan, Eli Lilly, Sage and Pfizer outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study and the interpretation of the results. Kinwah Fung conducted the statistical analysis. Simone Vigod and Serena Arora drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

Funding: Simone Vigod is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Shirley A. Brown Memorial Chair in Women’s Mental Health Research at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, Ontario. Marcelo Urquia holds a Canada Research Chair in Applied Population Health at the University of Manitoba.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/2/E227/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Ray JG, Zipursky J, Park AL. Injury-related maternal mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:307–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard LM, Flach C, Mehay A, et al. The prevalence of suicidal ideation identified by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in postpartum women in primary care: findings from the RESPOND trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuhr DC, Calvert C, Ronsmans C, et al. Contribution of suicide and injuries to pregnancy-related mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:213–25. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grigoriadis S, Wilton AS, Kurdyak PA, et al. Perinatal suicide in Ontario, Canada: a 15-year population-based study. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1085–92. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devries KM, Kishor S, Johnson H, et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18:158–70. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinker SC, Reefhuis J, Dellinger AM, et al. National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Epidemiology of maternal injuries during pregnancy in a population-based study, 1997–2005. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:2211–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiencrot A, Nannini A, Manning SE, et al. Neonatal outcomes and mental illness, substance abuse, and intentional injury during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:979–88. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0821-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendez-Figueroa H, Dahlke JD, Vrees RA, et al. Trauma in pregnancy: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace ME, Hoyert D, Williams C, et al. Pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide in 37 US states with enhanced pregnancy surveillance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:364 e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Hu W. Immigrant health, place effect and regional disparities in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2013;98:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vang ZM. Infant mortality among the Canadian-born offspring of immigrants and non-immigrants in Canada: a population-based study. Popul Health Metr. 2016;14:32. doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0101-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subedi RP, Rosenberg MW. Determinants of the variations in self-reported health status among recent and more established immigrants in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2014;115:103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, et al. Results of the Recent Immigrant Pregnancy and Perinatal Long-term Evaluation Study (RIPPLES) CMAJ. 2007;176:1419–26. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vang ZM, Sigouin J, Flenon A, et al. Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians? A systematic review of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. Ethn Health. 2017;22:209–41. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1246518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, Vigod S, et al. Prevalence of postpartum depression among immigrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spallek J, Reeske A, Norredam M, et al. Suicide among immigrants in Europe — a systematic literature review. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:63–71. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikram UZ, Mackenbach JP, Harding S, et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality of different migrant populations in Europe. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:655–65. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0083-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norredam M, Olsbjerg M, Petersen JH, et al. Are there differences in injury mortality among refugees and immigrants compared with native-born? Inj Prev. 2013;19:100–5. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maaten S, Guttman A, Kopp A, et al. Care of women during pregnancy and childbirth. In: Jaakkimainen L, Upshur REG, Klein-Geltink JE, et al., editors. Primary care in Ontario: ICES Atlas. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, et al. Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:135. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin L, Hirdes JP, Morris JN, et al. Validating the Mental Health Assessment Protocols (MHAPs) in the Resident Assessment Instrument Mental Health (RAI-MH) J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16:646–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirdes JP, Smith TF, Rabinowitz T, et al. Resident Assessment Instrument-Mental Health Group. The Resident Assessment Instrument-Mental Health (RAI-MH): inter-rater reliability and convergent validity. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2002;29:419–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02287348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: a validation study. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bethell J, Rhodes AE. Identifying deliberate self-harm in emergency department data. Health Rep. 2009;20:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annest JL, Hedegaard H, Chen L-H, et al. Proposed framework for presenting injury data using ICD-10-CM external cause of injury codes. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canadian Coding Standards For ICD-10-CA and CCI. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeMier M, Cummings P, West TA. Accuracy of external cause of injury codes reported in Washington State hospital discharge records. Inj Prev. 2001;7:334–8. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.4.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatov E, Kurdyak P, Sinyor M, et al. Comparison of vital statistics definitions of suicide against a coroner reference standard: a population-based linkage study. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63:152–60. doi: 10.1177/0706743717737033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Johns Hopkins ACG® System: excerpt from version 11.0 Technical Reference Guide. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University; 2015. Chapter 1: Diagnosis-based markers. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, et al. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1056–63. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oates M. Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:279–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gagnon AJ, Dougherty G, Wahoush O, et al. International migration to Canada: the post-birth health of mothers and infants by immigration class. Soc Sci Med. 2013;76:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganann R, Sword W, Black M, et al. Influence of maternal birthplace on postpartum health and health services use. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:223–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones I, Chandra PS, Dazzan P, et al. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Lancet. 2014;384:1789–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vigod S, Sultana A, Fung K, et al. A population-based study of postpartum mental health service use by immigrant women in Ontario, Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:705–13. doi: 10.1177/0706743716645285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryder AG, Yang J, Zhu X, et al. The cultural shaping of depression: somatic symptoms in China, psychological symptoms in North America? J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:300–13. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daoud N, O’Campo P, Urquia ML, et al. Neighbourhood context and abuse among immigrant and non-immigrant women in Canada: findings from the Maternity Experiences Survey. Int J Public Health. 2012;57:679–89. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyman I, Forte T, Du Mont J, et al. Help-seeking behavior for intimate partner violence among racial minority women in Canada. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kingston D, Heaman M, Urquia M, et al. Correlates of abuse around the time of pregnancy: results from a national survey of Canadian women. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:778–89. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y, Kane I, Wang J, et al. Combined use of the postpartum depression screening scale (PDSS) and Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) to identify antenatal depression among Chinese pregnant women with obstetric complications. Psychiatry Res. 2015;226:113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alisic E, Groot A, Snetselaar H, et al. Children bereaved by fatal intimate partner violence: a population-based study into demographics, family characteristics and homicide exposure. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heslehurst N, Brown H, Pemu A, et al. Perinatal health outcomes and care among asylum seekers and refugees: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Med. 2018;16:89. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1064-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halbreich U, Karkun S. Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2006;91:97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vigod SN, Bagadia AJ, Hussain-Shamsy N, et al. Postpartum mental health of immigrant mothers by region of origin, time since immigration, and refugee status: a population-based study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20:439–47. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edge D. Ethnicity, psychosocial risk, and perinatal depression — a comparative study among inner-city women in the United Kingdom. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:291–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.