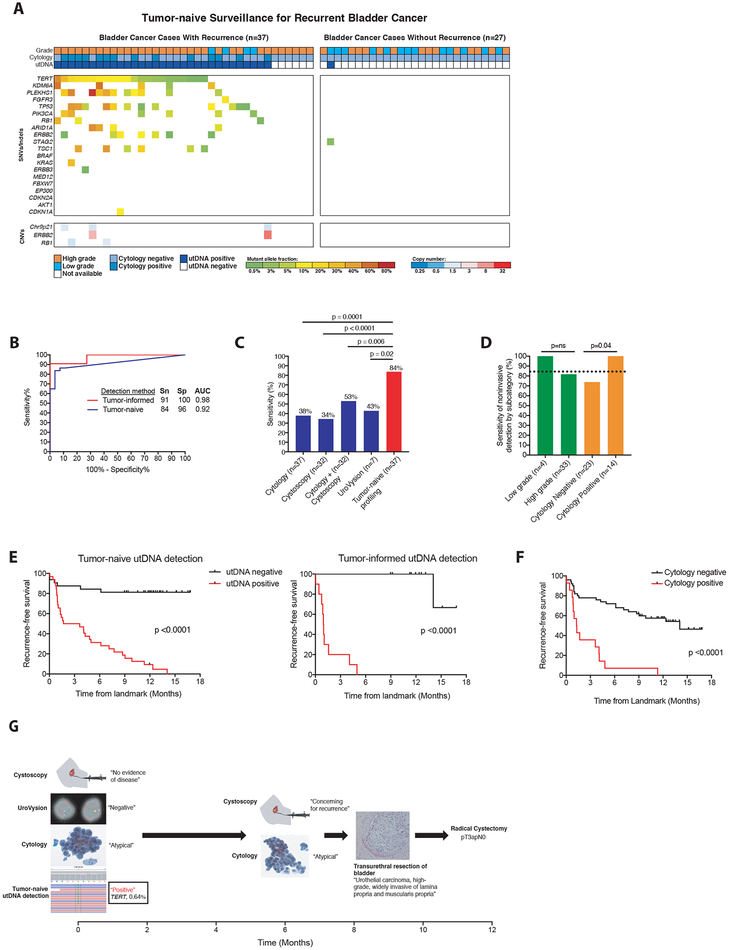

Figure 4: Application of uCAPP-Seq to detect residual disease in the surveillance setting.

(A) Distribution of putative driver mutations identified in urine cfDNA using tumor naïve profiling across cases that developed recurrent cancer (n=37) and cases with at least 9 months of negative clinical follow-up (n=27), with recurrent cancer defined by biopsy (32 cases) or alternative clinical evidence (5 cases), as specified in Supplemental Table S12. (B) Receiver operating characteristic analysis of tumor-naive profiling (n=37 cases and 27 controls) and tumor-informed profiling (n=11 cases and 11 controls) across surveillance group. (C) Comparison of the sensitivities of cytology (n=37), cystoscopy (n=32), cytology plus cystoscopy (n=32), UroVysion (n=7), and tumor-naive profiling (n=37) in detecting residual BLCA. (D) Correlates of sensitivity for detecting disease by tumor-naive profiling. P-values for (C) and (D) were calculated by the N-1 Chi Square test for comparing proportions. (E) Kaplan-Meier analysis of recurrence-free survival stratified by utDNA detection by tumor-naive and tumor-informed profiling (HR 8.8 and 27.3), respectively and (F) by cytology (HR 4.6). P-values and HR were calculated by the log-rank test. (G) Example of patient detected by tumor-naive profiling but missed by cystoscopy, cytology, and UroVysion who later was diagnosed with muscle-invasive bladder cancer, requiring a radical cystectomy. SNVs, single-nucleotide variants; CNVs, copy-number variants; Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; AUC, area under the curve; MRD, minimal residual disease; utDNA, urinary tumor DNA.