Abstract

Objective

To determine whether including Indigenous Elders as part of routine primary care improves depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in Indigenous patients.

Design

Prospective cohort study with quantitative measures at baseline and 1, 3, and 6 months postintervention, along with emergency department (ED) utilization rates before and after the intervention.

Setting

Western Canadian inner-city primary care clinic.

Participants

A total of 45 people who were older than age 18, who self-identified as Indigenous, and who had no previous visits with the clinic-based Indigenous Elders program.

Intervention

Participants met with an Indigenous Elder as part of individual or group cultural sessions over the 6-month study period.

Main outcome measures

Changes in depressive symptoms, measured with the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire), following Indigenous patients’ encounters with Indigenous Elders. Secondary outcomes included changes in suicide risk (measured with the SBQ-R [Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised]) and ED use.

Results

Characteristics among those who consented to participate were as follows: 71% were female; mean age was 49 years; 31% had attended residential or Indian day school; and 64% had direct experience in the foster care system. At baseline 28 participants had moderate to severe depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10). There was a 5-point decrease that was sustained over a 6-month period (P = .001). Fourteen participants had an above-average suicide risk score at baseline (SBQ-R score of ≥ 7), and there was a 2-point decrease in suicide risk that was sustained over a 6-month period (P = .005). For all participants there was a 56% reduction in mental health–related ED visits (80 vs 35) when comparing the 12 months before and after enrolment.

Conclusion

Encounters with Indigenous Elders, as part of routine primary care, were associated with a clinically and statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms and suicide risk among Indigenous patients. Emergency department use decreased, which might reduce crisis-oriented mental health care costs. Further expansion and evaluation of the role of Indigenous Elders as part of routine primary care is warranted.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer si le fait de faire participer des Aînés autochtones aux soins primaires habituels peut réduire les symptômes de dépression et les idées suicidaires chez les patients autochtones.

Type d’étude

Une étude de cohorte prospective utilisant des mesures quantitatives au point de départ, suivies d’interventions postérieures après 1, 3 et 6 mois, de concert avec les taux d’utilisation de l’urgence avant et après l’intervention.

Contexte

La clinique de soins primaires d’un quartier défavorisé d’une ville de l’Ouest canadien.

Participants

Un total de 45 personnes de plus de 18 ans, qui se déclaraient autochtones et qui n’avaient jamais rendu visite au programme des Aînés autochtones de la clinique.

Intervention

Les participants ont rencontré un Aîné autochtone dans le contexte de séances culturelles individuelles ou de groupe, au cours de la période de 6 mois qu’a duré l’étude.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Les changements observés dans les symptômes de dépression, tels qu’évalués au moyen du QSP-9 (Questionnaire sur la santé du patient), à la suite des rencontres des patients autochtones avec des Aînés autochtones. Parmi les paramètres secondaires, mentionnons les changements dans le risque de suicide (mesurés à l’aide du SBQ-R (Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised)) et les visites à l’urgence.

Résultats

Les caractéristiques des personnes ayant consenti à participer étaient les suivantes : 71 % étaient de sexe féminin; l’âge moyen était de 49 ans; 31 % avaient fréquenté le pensionnat ou l’externat indien; et 64 % avaient une exérience directe du système de placement familial. Au départ, 28 participants avaient des symptômes de dépression modérée ou sévère (score QSP de ≥ 10). Il y a eu une diminution de 5 points, maintenue sur une période de 6 mois (p =, 001). Parmi les participants, 14 avaient un risque de suicide au-dessus du score moyen au départ (score SBQ-R de ≥ 7), et il y a eu une diminution de 2 points du risque de suicide, maintenue sur une période de 6 mois (p =, 005). Chez tous les participants, il y a eu une réduction de 56 % des visites à l’urgence liées à la santé mentale (80 c. 35) en comparaison avec les 12 mois précédant et suivant l’engagement à participer.

Conclusion

Les rencontres avec des Aînés autochtones, en tant qu’éléments des soins médicaux courants, ont été associées à une réduction cliniquement et statistiquement significative des symptômes de dépression et du risque de suicide chez les patients autochtones. Le recours à l’urgence a diminué, ce qui est susceptible de réduire les coûts des soins de santé mentale en situation de crise. Il serait justifié d’élargir et d’évaluer davantage le rôle des Aînés autochtones dans le cadre des soins de santé primaires courants.

Indigenous people of Canada (inclusive of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people) possess a wealth of diverse healing traditions that have endured despite the cultural oppression of colonization.1 However, the current experience for many Indigenous people is one of disconnection from these traditions and high levels of mental and emotional distress that are reflected in persistently elevated rates of depression, suicidal ideation, and death by suicide.2–6 A wealth of Indigenous scholarship has shown that these disparities relate to underlying economic, social, and political inequities that are legacies of colonization and the government’s attempt at “cultural genocide,” as described by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada.7–13 This is particularly evident for Indigenous people living in inner cities where the influences of poverty and racism on mental illness are more overt.3,8,14,15

Primary and mental health services have generally not been adapted to serve the needs of Indigenous patients, which is reflected in relatively low rates of utilization.1,16 Identified reasons for this reluctance to access mainstream health care include racism, “being treated as second class citizens,”17 and lack of Indigenous staff and cultural practices.17–20 Many Indigenous people have experienced distrust and dismissal when accessing health care, which is often compounded for people living with serious mental health or substance use issues.19,21,22 Studies suggest that Indigenous people living in inner cities might turn to Indigenous Elders as sources of care in lieu of mainstream services.15

There is general agreement that Indigenous Elders can play an important role in the mental health of Indigenous people.16,17 Elders are those identified by the community as possessing qualities such as leadership, wisdom, compassion, community devotion, and dedication to personal healing.7,17,23,24 Experiencing a connection with Elders can allow individuals to assert or reclaim cultural identity and counter the marginalization experienced by many Indigenous people in health care settings.1,16 In contrast with the biomedical model, Elders tend to view mental illness in spiritual and social terms, as rooted in disconnection from families, traditions, communities, the land, and one’s self and spirit; and view healing as requiring the re-establishment of these connections.16

Cultural continuity, which relies upon a community’s effort to maintain its cultural institutions and practices, has been identified as a strong community-level protective factor against suicide among Indigenous peoples.25–27 Accordingly, guidelines for Indigenous suicide prevention call for programs that promote pride and control in the community, improve self-esteem and identity, transmit Indigenous knowledge, language and traditions, and employ culturally appropriate methods.28 These elements could be achieved through the meaningful inclusion of Elders in primary care programs. One of the TRC’s “calls to action” involves the inclusion of Elders in the treatment of Indigenous patients in Canadian health care systems.29 However, Elders are not recognized as legitimate care providers within Canada’s health care system, and there are no prospective studies exploring the implementation and effect of formally including Elders in the provision of primary health care. This study’s goal was to examine the effect of an Indigenous Elders program on the mental health of Indigenous patients in an inner-city primary care setting.

METHODS

This study is part of a mixed-methods investigation that followed patients prospectively. The study design was developed in consultation with an Elders and Community Advisory Committee. The study setting was an inner-city primary care clinic that was founded in 1991 to provide medical care to urban Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients. This clinic, described elsewhere in more detail,17 aims to provide interprofessional team-based care that is culturally informed and adapted to the context of the inner-city community. The primary care team is composed of family physicians, nurses, mental health counselors, a psychiatrist, and medical office support staff. The clinic has a panel of more than 4000 active patients, 65% of whom self-identify as Indigenous. Clinic patients are from more than 200 Indigenous communities from across North America. Many patients have serious mental illness, substance use problems, chronic pain, and other stigmatizing health conditions, such as HIV. In 2013, the clinic began a partnership program with a team of Indigenous Elders to provide mentorship to clinical staff and trainees, which expanded in 2014 to provide direct patient care through one-on-one visits, group cultural teaching sessions, and land-based ceremony. Five Elders worked collaboratively with the primary care team, attending shared clinical rounds and using a shared electronic medical record. Between 2014 and 2016, more than 300 clinic patients connected with the Elders program.

The target population for this study was adult Indigenous clinic patients who were interested in connecting with an Elder. Inclusion criteria included capacity to provide informed written consent, and no previous visits with the clinic-based Indigenous Elders program. Study participants were recruited from the clinic sequentially over a 12-month period. Demographic and social history data were collected at baseline.

The study aim was to measure the mental health effects of patients’ encounters with Indigenous Elders as part of routine primary care. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)30 was used as the primary outcome measure, and was completed by participants at baseline and 1, 3, and 6 months postintervention. Using an α error of .05, a β error of .2, and a loss to follow-up rate of 10%, a sample size of 44 participants was selected to detect a 5-point change on the PHQ-9. Patients with clinically significant depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10) were included in the analysis. A score of 10 or higher on the PHQ-9 has been shown to have a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for major depressive disorder.30 A per-protocol analysis approach was used—inclusive of all those who had at least 1 visit with an Elder and completed at least the 1-month follow-up.

Secondary objectives included measuring changes in suicidal ideation and emergency department (ED) use. Suicide risk was measured using the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised (SBQ-R).31 Data on ED use were extracted from patients’ primary care records with data linkages to the regional health authorities’ hospital utilization database. Emergency department visits were categorized into visits related to mental health and visits not related to mental health, and were ranked using the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale.32 Emergency department utilization rates were compared in the 12 months before and after enrolment. Paired t tests were used to compare means from all outcome measures before and after intervention.

Participants who had met with an Elder at least twice over their initial 3 months in the program were also invited to participate in a semistructured interview exploring their experiences with and perceptions of the Elders program. Qualitative findings are reported separately.33

We followed the Canadian Tri-Council guidelines on ethical research involving the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people. The University of British Columbia and the Vancouver Native Health Society granted ethics approval.

RESULTS

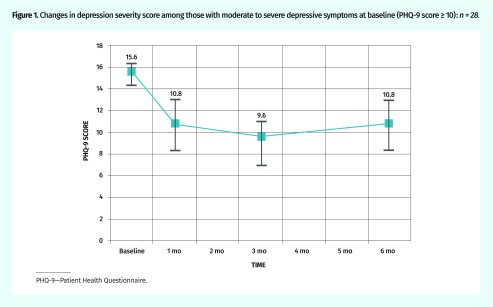

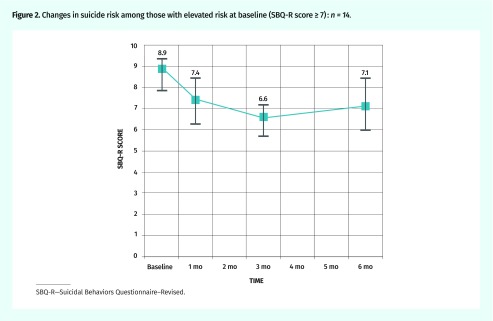

Forty-five eligible patients with diverse Indigenous backgrounds, representing 14 distinct nations, provided written consent to participate in the study. Baseline demographic characteristics and study measures are described in Table 1. Thirteen percent were from the urban centre where the study was conducted, 43% were from other parts of the province, and 43% were from out of province. Study retention was 91%, with 1 participant dropping out preintervention, 2 moving away before the first follow-up, and 1 death from a chronic illness during the beginning of the study period. The remaining 41 patients were followed longitudinally over 6 months; the mean number of Elder visits was 5 (range was 1 to 21 visits, median was 3 visits). There was no significant association between the number of visits and study outcomes. As shown in Table 2, 68% of participants had moderate to severe depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10) at baseline and 34% had elevated baseline risk of suicide (SBQ-R score of ≥ 7). There was a statistically significant 5-point and 2-point decrease in PHQ-9 and SBQ-R scores, respectively, at 1 month. These statistically significant reductions in depressive symptoms and suicide risk were sustained at the 3- and 6-month follow-up. These changes and their 95% CIs are shown graphically in Figures 1 and 2. Almost 40% (11 of 28) of “depressed” patients (PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10) had a greater than 50% reduction in symptoms.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics and study measures: N = 45.

| VARIABLES | VALUE |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| • Mean (range) age, y | 49 (25–76) |

| • Female sex, n (%) | 32 (71) |

| • Born in British Columbia, n (%)* | 25 (57) |

| • Attended residential school, n (%) | 14 (31) |

| • With ≥ 1 parents attending residential school, n (%) | 27 (60) |

| • Directly experiencing foster care, n (%) | 29 (64) |

| • Completing high school or postsecondary education, n (%) | 20 (44) |

| • Married or with common-law partner, n (%) | 13 (29) |

| • With stable housing (excluding SRO hotel room), n (%) | 23 (51) |

| Baseline study measures | |

| • Mean (range) PHQ-9 score (depression severity score)† | 12.4 (1–24) |

| • Mean (range) SBQ-R score (suicide risk score)‡ | 5.6 (3–12) |

PHQ-9—Patient Health Questionnaire, SBQ-R—Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised, SRO—single-room occupancy.

Data were available for only 44 patients.

Nine items, each of which is scored 0 to 3, providing a severity score between 0 and 27. Scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 represent cut points for mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.

Four items, scored variously. Total scores range from 3 to 18. A score ≥ 7 represents increased risk.

Table 2.

Changes in PHQ-9 depression severity scores and SBQ-R suicide risk scores over time for those with severe symptoms at baseline

| SEVERITY | N | MEAN SCORE | MEAN CHANGES FROM BASELINE (P VALUE) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| BASELINE | 1 MO | 3 MO | 6 MO | 1 MO | 3 MO | 6 MO | ||

| PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 | 28 | 15.6 | 10.8 | 9.6 | 10.8 | −4.9 (P = .002) | −6.2 (P < .001) | −4.5 (P = .001) |

| SBQ-R score ≥ 7 | 14 | 8.9 | 7.4 | 6.6 | 7.1 | −1.5 (P =.002) | −2.3 (P < .001) | −1.8 (P = .003) |

PHQ-9—Patient Health Questionnaire, SBQ-R—Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised.

Figure 1.

Changes in depression severity score among those with moderate to severe depressive symptoms at baseline (PHQ-9 score 10): n = 28.

PHQ-9—Patient Health Questionnaire.

Figure 2.

Changes in suicide risk among those with elevated risk at baseline (SBQ-R score 7) : n = 14.

SBQ-R—Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised.

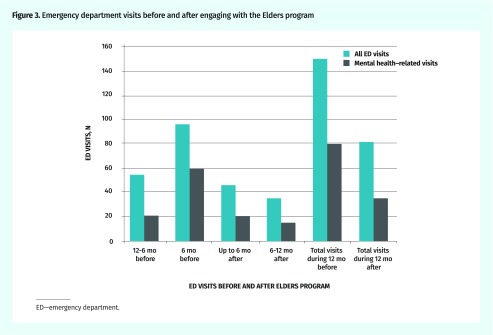

Changes in ED use are shown in Figure 3; there was a 46% reduction in total ED visits (150 vs 81) and a 56% reduction in mental health–related ED visits (80 vs 35). Of those visits related to mental health, 97% had Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale scores of 4 (semiurgent) or 5 (nonurgent)—situations often viewed as failures of primary care to prevent a crisis. The mean number of ED visits related to mental health per participant decreased from 1.9 to 0.8 visits per year (P = .11).

Figure 3.

Emergency department visits before and after engaging with the Elders program

ED—emergency department.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study of Indigenous Elders as part of routine primary care for Indigenous patients. We found clinically and statistically significant sustained reductions in depressive symptoms and suicide risk. Although the study design constrains any claims of causality, analysis of semistructured interviews with 28 of the study participants strongly linked these mental health improvements to their connecting with an Elder.33 Participants described being able to establish trust and openness with the Elders, which they contrasted with their experiences with mainstream mental health providers, and this allowed them to address the negative effects of colonial oppression on their mental health. Encounters with Elders instilled hope as they provided opportunities to strengthen cultural identity and belongingness, and to address the spiritual dimensions that are the underlying source of the depressive symptoms through participation in ceremony. No harms were identified in the qualitative analysis.

The Elders’ effectiveness at reducing suicidal ideation likely relates to their ability to mobilize known protective factors against suicide, such as providing social supports; promoting a sense of belonging; connecting with family, peers, and community; drawing on spiritual, religious, or moral beliefs; and developing a positive self-appraisal and identity.34 These study results are in line with a previous study that showed a decrease in teen suicide rate with the inclusion of Elders in a mental health promotion strategy.35

Our findings suggest that encounters with Elders can provide a meaningful adjunct or alternative to conventional services for Indigenous peoples with emotional distress, including symptoms of severe depression. The observed decrease in ED use could also have considerable cost-saving implications for the health system. The study supports the proposition that Indigenous Elders can play an important role in the mental health of Indigenous people, especially as part of the key process of regaining positive cultural identity and supporting cultural continuity.1 The Elders who provided the intervention in this study chose to participate in order to address the lack of support, respect, and funding for Indigenous Elders in the mainstream health system. They also voiced serious concerns about the cultural appropriateness of having their practice evaluated “scientifically.” The study was designed to evaluate the effect of this cultural intervention on Indigenous patients who were inclined to visit with an Indigenous Elder to address some form of distress or discontent, which in many cases included manifestations of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, but it was not designed to specifically evaluate the efficacy of the Elders program for treating depression.

Limitations

Although almost 40% of “depressed” patients had a greater than 50% reduction in symptom severity, the study’s design lacked a control comparator group, which limits speculation on the magnitude of benefit of the intervention. No study participants were excluded based on medical or psychiatric comorbidities, pharmacotherapies, or concurrent substance use disorder, and these other conditions could have influenced the outcomes of this study. The study team accepted these limitations on the recommendation of the study’s Elder and Community Advisory Committee, which expressed that, from an Indigenous perspective, it would be unethical to limit or randomly deny access to patients who wanted to see an Elder. However, the study’s setting within patients’ own primary care clinic and lack of exclusion criteria increases the ecological validity of the findings and their potential application to the real world of inner-city primary care.

Similar to our sample of participants, Indigenous people living in inner cities often have very diverse geographic and cultural backgrounds, and therefore only a minority of participants had access to an Elder with the same cultural background and traditions. Although this limitation might have potentially reduced the effectiveness of participants’ encounters with Elders—that is, patients could have derived greater benefit from engaging with an Elder from their communities of origin—many participants welcomed the opportunity to learn “new” traditions and practices, while others had no previous experience with cultural traditions or Elders from their home territory.33

Further research should attempt to verify this study’s signal of benefit through a randomized, multisite design involving both urban and rural communities. Future studies should also explore the importance of connecting with an Elder from the same versus distinct cultural traditions, and evaluate whether the inclusion of Indigenous Elders in primary care might affect other conditions such as substance use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or chronic pain.

Conclusion

This study supports the proposition that the inclusion of Indigenous Elders within mainstream primary health care services can statistically significantly reduce depressive symptoms and suicidality, and contribute to eliminating mental health disparities for Indigenous people. Further, such interventions can potentially lower health care costs by increasing primary care effectiveness and reducing the use of costly emergency and crisis-oriented services. This study’s findings strongly support the TRC call to action to include Indigenous Elders in the treatment of Indigenous patients within the Canadian health care system.

Acknowledgments

The Canadian Institute for Health Research and the Community Action Initiative provided funding for this study. The Vancouver Native Health Society provided material support.

Editor’s key points

▸ Cultural continuity has been identified as a strong protective factor against suicide among Indigenous people. Suicide programs for Indigenous people should include promoting pride and control in the community, improving self-esteem and identity, transmitting Indigenous traditions, and employing culturally appropriate methods. These elements could be achieved through the meaningful inclusion of Elders into primary care programs.

▸ The findings suggest that encounters with Elders can provide a meaningful adjunct or alternative to conventional services for Indigenous people with emotional distress, including symptoms of severe depression and elevated risk of suicide. The observed decrease in emergency department use could also have considerable cost-saving implications for the health system.

▸ The Elders’ effectiveness at reducing suicidal ideation likely relates to their ability to mobilize known protective factors against suicide, such as promoting a sense of belonging; connecting with family, peers, and community; drawing on spiritual, religious or moral beliefs; and developing a positive identity.

Points de repère du rédacteur

▸ Il a été établi que la continuité culturelle est un solide facteur de protection contre le suicide chez les Autochtones. Les programmes de prévention du suicide chez les Autochtones devraient promouvoir la fierté et le contrôle dans la communauté, améliorer l’estime de soi et l’identité personnelle, favoriser la transmission des traditions autochtones et utiliser des méthodes culturellement appropriées. Ces objectifs pourraient être atteints par une inclusion significative des Aînés autochtones dans les programmes de soins primaires.

▸ Ces constatations laissent entendre que des rencontres avec des Aînés peuvent représenter un complément ou une solution de remplacement intéressants aux services habituels destinés aux Autochtones qui présentent des problèmes de détresse émotionnelle, y compris des symptômes de dépression sévère ou un risque élevé de suicide. La diminution de l’utilisation de l’urgence pourrait aussi entraîner une diminution des coûts pour le système de santé.

▸ La capacité des Aînés de réduire les idées suicidaires dépend probablement de leur capacité de susciter les facteurs connus de protection contre le suicide, comme la promotion d’un sentiment d’appartenance; les liens avec la famille, les pairs et la communauté; l’appui sur les croyances spirituelles, religieuses ou morales; et le développement d’une identité positive.

Footnotes

Contributors

Dr Tu was co–principal investigator and contributed to the development of the research concept and protocol; attainment of funding; implementation of the intervention; data collection; data analysis; and writing and revision of the manuscript. Dr Hadjipavlou was co–principal investigator and contributed to the development of the research concept and protocol; attainment of funding; supervision of research staff; data collection; data analysis; and writing and revision of the manuscript. Mrs Dehoney was a co-investigator and contributed to the development of the research concept and protocol; attainment of funding; data collection; data analysis; and revision of the manuscript. Elder Price was a co-investigator and Elder Advisor, and contributed to the development of the research concept; implementation of the study intervention; data analysis; and revision of the manuscript. Mr Dusdal was a research assistant and contributed to data collection, data analysis, creation of manuscript figures, and revision of the manuscript. Dr Browne was a co-investigator and research mentor, and contributed to the development of the research concept and protocol; attainment of funding; data collection; data analysis; and revision of the manuscript. Dr Varcoe was a co-investigator and research mentor, and contributed to the development of the research concept and protocol; attainment of funding; data collection; data analysis; and revision of the manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

References

- 1.Kirmayer LJ, Tait C, Simpson C. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada: transformations of identity and community. In: Kirmayer LJ, Valaskakis G, editors. Healing traditions. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press; 2009. pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirmayer LJ, Brass GM, Holton T, Ken P, Simpson C, Tait C. Suicide among Aboriginal people in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wingert S. The social distribution of distress and well-being in the Canadian Aboriginal population living off reserve. Int Indig Policy J. 2011;2(1):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemstra M, Neudorf C, Mackenbach J, Kershaw T, Nannapaneni U, Scott C. Suicidal ideation: the role of economic and Aboriginal cultural status after multivariate adjustment. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):589–95. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tjepkema M. The health of the off-reserve Aboriginal population. Health Rep. 2002;13(Suppl):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.First Nations Centre . First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (RHS) 2002/03. Results for adults, youth, and children living in First Nations communities. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Centre; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples . Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa, ON: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirmayer L, Simpson C, Cargo M. Healing traditions: culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;11:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elias B, Mignone J, Hall M, Hong SP, Hart L, Sareen J. Trauma and suicide behaviour histories among a Canadian indigenous population: an empirical exploration of the potential role of Canada’s residential school system. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(10):1560–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.026. Epub 2012 Mar 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in Aboriginal Canada. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl 2):S45–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03403702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown HJ, McPherson G, Peterson R, Newman V, Cranmer B. Our land, our language: connecting dispossession and health equity in an indigenous context. Can J Nurs Res. 2012;44(2):44–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaspar V. Long-term depression and suicidal ideation outcomes subsequent to emancipation from foster care: pathways to psychiatric risk in the Metis population. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215(2):347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.09.003. Epub 2013 Dec 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benoit C, Carroll D, Chaudhry M. In search of a healing place: Aboriginal women in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(4):821–33. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Culhane D. Narratives of hope and despair in Downtown East Vancouver. In: Kirmayer LJ, Valaskakis G, editors. Healing traditions. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press; 2009. pp. 160–77. [Google Scholar]

- 16.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menzies P, Bodnar A, Vern Harper E, Aboriginal Services The role of the Elder within a mainstream addiction and mental health hospital: developing an integrated paradigm. Native Soc Work J. 2010;7:87–107. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browne AJ, Varcoe CM, Wong ST, Smye VL, Lavoie J, Littlejohn D, et al. Closing the health equity gap: evidence-based strategies for primary health care organizations. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Browne AJ, Smye VL, Rodney P, Tang SY, Mussell B, O’Neil J. Access to primary care from the perspective of Aboriginal patients at an urban emergency department. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(3):333–48. doi: 10.1177/1049732310385824. Epub 2010 Nov 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang SY, Browne AJ. ‘Race’ matters: racialization and egalitarian discourses involving Aboriginal people in the Canadian health care context. Ethn Health. 2008;13(2):109–27. doi: 10.1080/13557850701830307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smye V, Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Josewski V. Harm reduction, methadone maintenance treatment and the root causes of health and social inequities: an intersectional lens in the Canadian context. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Fridkin A. Addressing trauma, violence and pain: research on health services for women at the intersections of history and economics. In: Hankivsky O, editor. Health inequities in Canada: intersectional frameworks and practices. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press; 2011. pp. 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellerby JH. Working with indigenous elders: an introductory handbook for institution-based and health care professional based on the teachings of Winnipeg-area aboriginal elders and cultural teachings. 3rd ed. Winnipeg, MB: Native Studies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehl-Madrona L. What traditional indigenous elders say about cross-cultural mental health training. Explore (NY) 2009;5(1):20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE. Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide. Transcult Psychiatry. 1998;35(2):191–219. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandler MJ, Lolande CE. Cultural continuity as a moderator of suicide risk among Canada’s First Nations. In: Kirmayer LJ, Valaskakis G, editors. Healing traditions. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press; 2009. pp. 221–48. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodnar A. Perspectives on Aboriginal suicide: movement toward healing. In: Menzies P, Lavallée LF, editors. Journey to healing. Aboriginal people with addiction and mental health issues. What health, social service and justice workers need to know. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2014. pp. 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acting on what we know. Preventing youth suicide in First Nations. The report of the Advisory Group on Suicide Prevention. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2002. Available from: www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/fniah-spnia/alt_formats/fnihb-dgspni/pdf/pubs/suicide/prev_youth-jeunes-eng.pdf. Accessed 2017 Oct 20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: calls to action. Winnipeg, MB: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015. Available from: https://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf. Accessed 2019 Feb 27. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. 2001;8(4):443–54. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Implementation guidelines for the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians; 1998. Version CTAS16.DOC. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadjpavilou G, Varcoe C, Tu D, Dehoney J, Price R, Brown AJ. “All my relations”: experiences and perceptions of Indigenous patients connecting with Indigenous Elders in an inner city primary care partnership for mental health and well-being. CMAJ. 2018;190(20):E608–15. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.171390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar MB, Walls M, Janz T, Hutchinson P, Turner T, Graham C. Suicidal ideation among Métis adult men and women—associated risk and protective factors: findings from a nationally representative survey. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012;71:18829. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neligh G. Mental health programs for American Indians: their logic, structure and function. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res Monogr Ser. 1990;3:1–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]