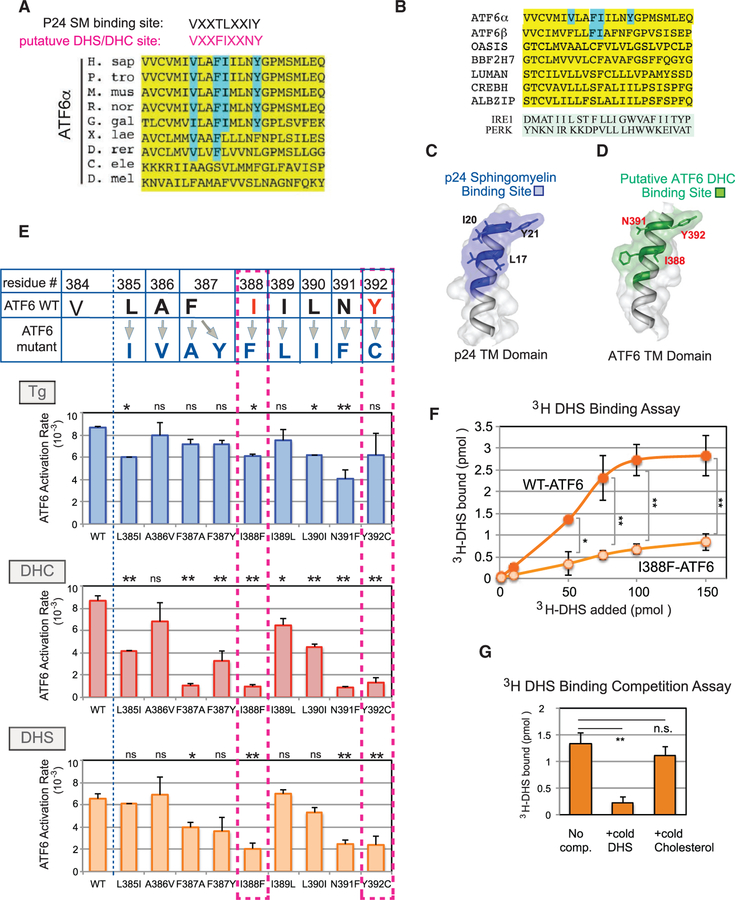

Figure 5. A Conserved Dihydroceramide- and Dihydrosphingosine-Recognition Motif Is Found within the ATF6 Transmembrane Domain.

(A) Alignment of residues within the transmembrane domain of ATF6 (yellow). The previously reported consensus binding site (VXXTLXXIY) for sphingomyelin (SM) in the COP I component p24 (Contreras et al., 2012) is shown for comparison with a putative DHS-binding site in ATF6 (VXXFIXXNY, red), proposed here. Residues within the DHS recognition motif that map in equivalent locations to the essential residues of p24 are highlighted in blue. (B) Sequence alignment of the transmembrane domains of ATF6α, ATF6β, and other transmembrane transcription factors, including OASIS, BBF2H7, LUMAN, CREBH, and ALBZIP, is shown. For comparison, the transmembrane domains of IRE1 and PERK are also shown. The VXXFIXXNY motif was not seen in IRE1 or PERK. (C and D) Predicted structural models of the p24 sphingomyelin-binding motif within its transmembrane domain (C) and the putative DHS-binding motif within the ATF6 transmembrane domain (D) were derived from the computational program Phyre2. The N termini are at the bottom of the image and the C termini at the top. The sphingomyelin-binding motif of p24 is shown (C), with the key residues L17, I20, and Y21 indicated (Contreras et al., 2012). The spatial relationships of three conserved residues, I388, N391, and Y392 in the DHS-recognition motif are highlighted in red (D). (E) Each residue within the putative DHS or DHC recognition motif of ATF6 was mutated to the amino acid residues shown in dark blue. Within the motif, critical amino acid residues for activation by DHS and DHC are shown in red. The activation rate of the individual ATF6 mutants was measured upon Tg, DHC, or DHS treatment of HEK293 cells carrying the mutants. In particular, I388F-ATF6 and Y392C-ATF6 were diminished for activation by DHC and DHS, but retained the ability to be activated by Tg. Data represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments, each with at least 50 cells per sample. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n.s. indicates statistically insignificant differences, using unpaired two-tailed t tests comparing activation rate of WT versus mutants samples. Note that an amino acid change at the valine (V384) caused constitutive activation of ATF6 even in the absence of Tg or DHS/DHC, and thus was omitted from mutational analysis (Figure S5A). (F) WT-ATF6 binds to [3H]DHS in a concentration-dependent manner and reaches a plateau at 100 pmol. The I388F-ATF6 mutant was severely diminished in its ability to bind to [3H]DHS. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 using unpaired two-tailed t tests comparing WT-ATF6 and I388F-ATF6 at each [3H]DHS concentration added. Each experiment was repeated at least three independent times. (G) Association of WT-ATF6 with [3H]DHS was effectively competed by addition of excess cold DHS, but unchanged by addition of the excess unrelated lipid cholesterol. **p < 0.01 using unpaired two-tailed t tests comparing the 3H-bound values of no competitor versus addition of cold DHS, while n.s. (not significant) compares the values between no competitor and added cold cholesterol. Each experiment was repeated at least three independent times.