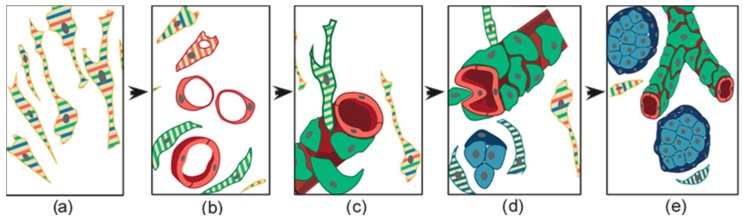

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the histogenesis of head and neck paraganglioma, based on patient- and cell-derived xenograft models. The thin elongated stem-like cells (a), stabilized and expanded in paraganglioma cell cultures, co-express (stripes) multipotent stem/progenitor cell markers. In vivo, (b) these cells grow on autonomously synthesized extracellular matrix, develop intracytoplasmic vacuoles of increasing size (cells with red stripes only), and coalesce (uniformly red cells), giving rise to endothelial tubes (vasculogenesis via cytoplasmic hollowing). The endothelium then recruits adjacent stem-like cells (cells with green stripes only), which, after contact with the abluminal endothelial membranes (c), differentiate into mural cells (uniformly green). (d) The panel outlines two remarkable consequences of mural stabilization. First, mural impingement results in intraluminal endothelial intussusceptions, which divide the flow, giving rise to Y-shaped vascular ramifications (intussusceptive angiogenesis, a process detectable only with whole-mount confocal microscopy and/or transmission electron microscopy, as used in our study [56]). Secondly, vascular stabilization results in perivascular deposition of collagen IV [56], which supports the development of cell clusters with neural phenotype (cells with blue stripes only, then uniformly blue). As shown in (e), these clusters develop into “zellballen”-like neuroepithelial nests (uniform light blue), bound by spindle-shaped glia-like cells (uniform dark blue). Notably, while mesenchymal paraganglioma stem-like cells have normal mitochondria, paraganglioma tissue organization is associated with increasing mitochondrial dysfunction (swelling and loss of membrane potential), culminating in the neuroepithelial component. Original art by Giulio Pandolfelli, adapted and modified from Verginelli et al., 2018 [56].