Abstract

In mammals, preimplantation development primarily occurs in the oviduct (or fallopian tube) where fertilized oocytes migrate through, develop and divide as they prepare for implantation in the uterus. Studies of preimplantation development currently rely on ex vivo experiments with the embryos cultured outside of the oviduct, neglecting the native environment for embryonic growth. This prevents the understanding of the natural process of preimplantation development and the roles of the oviduct in early embryonic health. Here, we report an in vivo optical imaging approach enabling high-resolution visualizations of developing embryos in the mouse oviduct. By combining optical coherence microscopy and a dorsal imaging window, the sub-cellular structures and morphologies of unfertilized oocytes, zygotes, and preimplantation embryos can be well resolved in vivo, allowing for the staging of development. We present the results together with bright-field microscopy images to show the comparable imaging quality. As the mouse is OCM through a dorsal imaging window enables high-resolution imaging and staging of mouse preimplantation embryos in vivo in the oviduct.

Keywords: optical coherence microscopy, preimplantation development, oviduct, mouse, in vivo imaging

Graphical Abstract

Mammalian preimplantation development primarily takes place in the oviduct. Optical imaging provided indispensable tools for studying this process, yet investigations have been largely limited to ex vivo experiments with embryos studied in culture, outside of their native environment. Here, we report an in vivo high-resolution imaging approach combining optical coherence microscopy with a dorsal imaging window to provide sub-cellular details of mouse preimplantation embryos in the oviduct.

1. Introduction

In mammals, following fertilization, the embryo develops while passing through the oviduct (fallopian tube) before implanting in the uterus. This period of preimplantation development consists of several critical stages with distinct cellular and molecular activities defining embryo health and viability [1]. The mouse is a well-established model with powerful genetic engineering strategies for studying mammalian reproduction and embryonic development [2]. So far, our understanding of the preimplantation developmental process has been obtained primarily from ex vivo culturing experiments [3–6]. In vivo analysis of preimplantation embryos in the oviduct, their native growing environment, is largely absent, due to the lack of imaging approaches able to generate desired visualizations through tissue layers. The oviduct supplies a complex biochemical and biomechanical environment for the early embryo [7, 8], which is hard to model under ex vivo settings. This technical hurdle prevents the understanding of the natural process of preimplantation development and limits the studies of interactions between embryos and the oviduct. Such missing knowledge is of significant value to improve the management of infertility and in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Traditionally, bright-field microscopy is employed to obtain a quick and convenient 2D view of the cell position and morphology of preimplantation embryos, while for 3D information, fluorescent-based confocal and multiphoton microscopies are usually utilized to gain detailed access of the subcellular components. Recently, the emergence of interference-based quantitative phase microscopy [9] has achieved label-free 3D imaging of the preimplantation embryo, eliminating the phototoxity and photobleaching problems from fluorescent imaging and enabling cell characterization for IVF when vital reporters cannot be used. Although these modalities provide a set of useful tools for live investigations of preimplantation embryos, removal of embryonic cells from the female reproductive tract is required. In doing so, we lose the potential for in vivo study of preimplantation development in the oviduct.

Optical coherence microscopy (OCM), a noninvasive low-coherence imaging modality, was recently employed to study preimplantation embryos in 3D with a high spatial resolution [10–14]. OCM is a microscopy derivation of optical coherence tomography (OCT) [15]. With a higher magnification imaging lens, OCM provides an improved transverse resolution (1–2 µm), while maintaining a similar axial resolution (1–10 µm), in comparison with OCT. The full-field configuration of OCM [16] has been extensively used to image cellular structures of oocytes [10], zygotes [11], and preimplantation embryos [11]. Studies have also been performed to understand the 3D geometry of the first cleavage [12] and the morphological changes induced by vitrification [13]. Using a spectral-domain OCM system with a supercontinuum laser, Karnowski et al. captured the dynamics of zygotic nuclei movement and the first embryonic division [14], which demonstrated OCM as a promising label-free high-resolution 3D imaging tool to study preimplantation development at a sub-cellular scale. However, all previous work was conducted with ex vivo conditions, and whether OCM could provide in vivo characterization of preimplantation embryos remains to be explored.

Our group has recently developed in vivo OCT-based imaging approaches to assess the structure, morphology, and function of the mouse oviduct [17, 18], as well as the cellular dynamics inside the oviduct [19]. For prolonged and longitudinal imaging, we have implemented a 3D-printed intravital imaging window in combination with OCT, with minimal alterations of the local tissue environment [20]. Here, we demonstrate the feasibility of using OCM to image and stage the mouse preimplantation development in vivo. This study opens new exciting opportunities to understand the early developmental process naturally taking place in the oviduct and to investigate interactions of the oviduct with preimplantation embryos, which may provide insights for better management of infertility and the further improvement of assisted reproductive technology (ART).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. OCM system

The OCM employed in this study was based on a spectral-domain OCT system previously described in detail [18]. The system uses a broadband laser with a central wavelength of ~810 nm and a bandwidth of ~110 nm. A 10x scan lens (LSM02-BB, Thorlabs) was used to provide a transverse resolution of ~2 µm, sufficient to resolve the sub-cellular structures, such as the nuclei of the mouse oocytes, zygotes, and preimplantation embryos. The OCM system had an axial resolution of ~5 µm in tissue. The A-scan rate was up to ~68 kHz with the full 4096 pixels of the camera in use. A set of galvanometer mirrors were used for transverse scanning of the laser beam. The B-scan rate was set as 50 Hz with 1200 A-scans per B-scan. With 1200 B-scans per volume, the data acquisition of each OCT volume took 24 seconds. During imaging, the spatial sampling intervals were selected to have both transverse directions oversampled to preserve the resolution.

2.2. Implantation of the imaging window

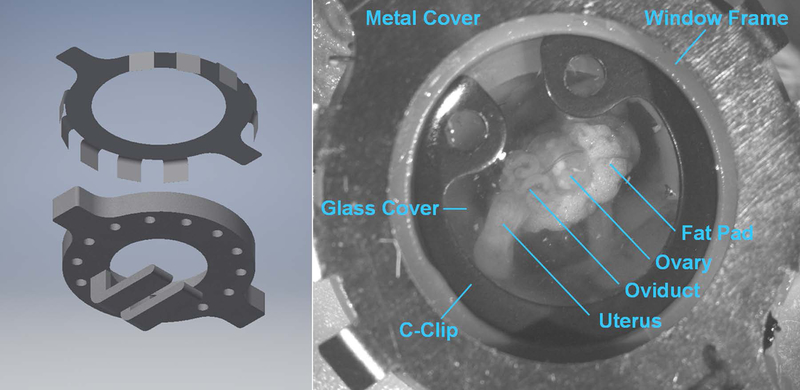

For in vivo OCM imaging of embryos within the reproductive organs, an intravital imaging window was utilized and surgically implanted as previously described [20]. The imaging window was produced using a 3D liquid printer (Form2, Formlabs). The window had a clear aperture of 10 mm, covered by a circular cover glass (12 mm diameter) to form a closed chamber. To avoid motion artifacts, the reproductive organs were positioned and stabilized on the tissue holders protruding from the chamber below the aperture. (Figure 1, left). To protect the window from being chewed on by the mouse, we designed a thin metal cover (Figure 1, left) that is glued to the surface of the window frame following surgery.

Figure 1.

The dorsal intravital window for in vivo OCM imaging of the preimplantation embryos. (Left) Illustration of the window and protective metal cover. (Right) A close-up picture of the window taken in vivo.

One hour prior to implantation of the imaging window, the female mouse was subcutaneously administered a one-time dose of 1 mg/kg sustained-release buprenorphine. The anesthetized female (by Isoflurane) was placed on a 37 °C operating table (with homeothermic temperature control) and was prepared for surgery with ophthalmic ointment placed on the eye and hair removed from the right dorsal region. The skin was then disinfected by wiping with a betadine scrub and removing with a 70% ethanol wipe three times. Lidocaine cream was spread over the surgical site to numb the skin prior to cutting. A circle of skin tissue with diameter of ~1 cm was removed, and the window frame was sutured onto the skin with 4–0 Nylon suture. A small incision (length of ~2 mm) was then made to the muscle layer. The reproductive organs were located and the ovary, the oviduct and about 5 mm of the uterus were gently pulled out of the body cavity through the incision by grabbing the fat pad associated with the ovary. The fat pad was then positioned and secured on the tissue holders with a drop of tissue adhesive to have the oviduct facing up. The space surrounding the reproductive organs was filled with 37°C sterile saline, and a circular glass coverslip was used to close the window aperture. A c-clip was placed over the coverslip, and tissue adhesive was added to the window eyelet holes and suture knots to prevent leaking or loosening. Once completed, the metal cover was glued down to the window frame. To minimize discomfort following surgery, mice were given rimadyl food tablets for anti-inflammation and one subcutaneous injection of 10 mg/kg Ketoprofen every 24 hours for three successive days. Mice with the window implanted exhibited normal behavior without signs of pain and discomfort, could mate naturally within a few days with successful embryo implantation. Figure 1 (right) shows close-up view of the implanted intravital imaging window in vivo.

All the procedures were performed according to the animal protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine.

2.3. Imaging and data processing

Adult female CD-1 mice (6–8 weeks of age) were used for experiments. For unfertilized oocytes, the estrous cycles of mice were monitored with established approaches [21], and the estrous phase was selected as the time point for imaging. For zygotes and preimplantation embryos, timed matings were set and checked for vaginal plugs every morning. The day when a plug was found was considered as 0.5 days post conception (dpc), and experiments were performed on 0.5 dpc, 1.5 dpc, and 2.5 dpc cells to study the feasibility of in vivo staging and imaging of the cellular structures.

For in vivo experiments of the specific time points, the mice first underwent window implantation surgery and were then imaged by OCM with both 2D and 3D scanning schemes. Following in vivo OCM data collection, in vitro imaging was conducted to confirm the stages of oocytes and preimplantation development. Bright-field and OCM were both utilized to perform in vitro validation experiments. The oocytes, zygotes, and embryos were extracted according to established protocols by removing and then flushing the oviduct with 37°C phosphate-buffered saline [22–24]. An upright Zeiss microscope (Imager.A2) with a 40x lens was employed for bright-field imaging.

The images were processed using the Imaris software (Bitplane). For visualization purposes, in addition to the traditional grey scale OCT images, we presented an overlay of the same structural data as two channels (blue and magenta) with different threshold settings. The thresholding for two channels was separately adjusted to produce improved contrast between the inner cells of the oocytes/embryos and the outer zona pellucida.

3. Results and Discussion

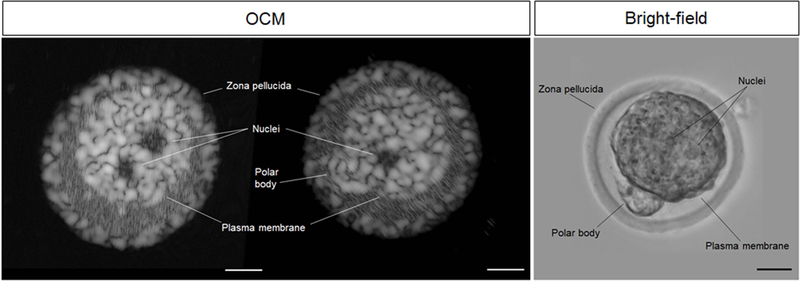

To investigate what level of structural detail can be achieved with OCM in imaging oocytes, zygotes and preimplantation embryos with our OCM system, we first performed in vitro comparative analysis between the OCM and bright-field microscopy. Figure 2 shows the same stage mouse zygote in vitro (0.5 dpc) imaged with OCM (left panel) and bright-field microscopy (right panel). Cross-sections through the volumetric data set acquired with OCM provide a high-contrast visualization of detailed sub-cellular structures of the zygote, including the nuclei, polar body, plasma membrane, and zona pellucida (Media 1). The resolution of the images is sufficient to analyze the size, position, and morphology of these structures. While OCM provides lower resolution images than the traditional bright-field microscopy, it has some advantages even in in vitro settings. While bright-field microscopy is two-dimensional, OCM imaging is volumetric and provides comparable and even better visualization of some cellular features, such as nuclei.

Figure 2.

In vitro OCM and bright-field images of zygotes (0.5 dpc) showing the structural anatomy, including the nuclei, polar body, plasma membrane, and zona pellucida. Cross-sectional OCM images (Media 1) clearly show major intracellular structures seen with bright-field microscopy. All scale bars are 20 µm.

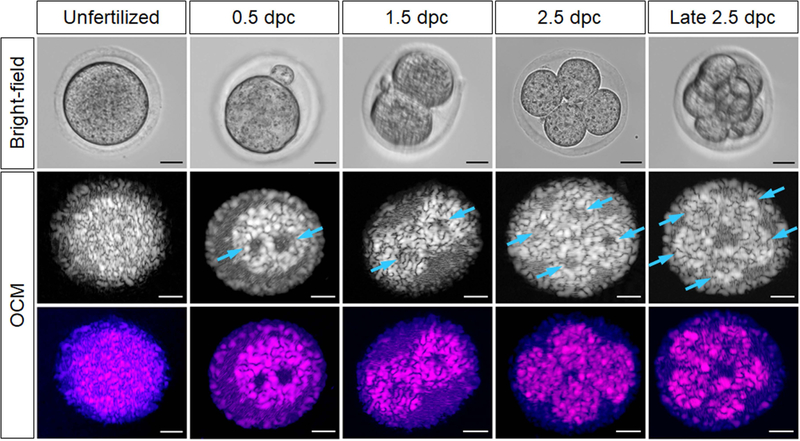

This superior resolvability of OCM in comparison to bright-field microscopy is consistent across different preimplantation stages (Figure 3, Media 1, and Media 2). Oocytes/embryos at 0.5 dpc were found in the ampulla, 1.5 dpc embryos were found in the isthmus, and 2.5 dpc embryos were generally located the utero-tubal junction. Compared with unfertilized oocytes, the nuclei of zygote are clearly revealed by OCM (pointed by arrows); one is contributed by an oocyte and the other one by a sperm. This ability to visualize nuclei can potentially be used to track the process of fertilization and differentiate between unfertilized and fertilized oocytes. As development progresses and preimplantation embryos undergo cleavage, the cell number is clearly distinguishable in OCM reconstructions, allowing for staging the embryos. Figure 3 shows two-cell, four-cell, and eight-cell stages at the 1.5, 2.5 and late 2.5 dpc, respectively. Media 3 and Media 4 present the corresponding volumetric data at late 2.5 dpc. At the stages of 0.5–2.5 dpc, the cell nuclei can be well resolved with sufficient contrast, while at late 2.5 dpc, the reduced size of the cells makes nuclei hard distinguish from OCM image. At later stages, as the cells become progressively smaller and embryos advance toward compaction, cell counting through OCM images also becomes problematic. In comparison to bright-field microscopy, OCM images contain speckles resulting from the use of coherence light, which also reduce the spatial resolving ability.

Figure 3.

In vitro bright-field and OCM images of the oocyte, zygote, and preimplantation embryos of different stages (Media 2, Media 3, and Media 4). Over all stages, the cross-sectional OCM images reveal comparable structural information (e.g. zona pellucida, nuclei, cell number and morphology) with the bright-field images. The bottom row shows the same OCT images in color scale for visibility (described in Materials and Methods section). Arrows point at nuclei at 0.5–2.5 dpc and cells at late 2.5 dpc. All scale bars are 20 µm.

After in vitro validation, we performed in vivo OCM imaging of oocytes, zygotes and embryos within the oviduct through an intravital dorsal imaging window. Overall, the level of structural detail achievable with OCM in imaging of oocyte, zygote, and preimplantation embryos in vitro and in vivo was comparable (Figure 4 and Media 5). The imaging depth of OCM allows for imaging through the whole depth of the oviduct lumen in vivo. Unfertilized oocytes at estrous phase and zygotes at 0.5 dpc were located in the ampulla of the oviduct. Embryos at 1.5 dpc were located in the isthmus. At 2.5 dpc, embryos were imaged in close proximity to the utero-tubal junction, about to enter the uterus. As one can see from Figure 4, the two nuclei of the zygote are clearly distinguished allowing differentiation between fertilized and unfertilized oocytes. At 1.5 dpc, the OCM image provides a cross-sectional view of the two-cell stage with the nuclei in the center of each cell. At 2.5 dpc, the imaged embryo has proceeded to the four-cell stage or higher. While the morphology of the embryo at 2.5 dpc is clearly distinct from earlier stages, faster movements of the embryos in the isthmus due to oviduct smooth muscle contractions, smaller size of individual cells and initiation of compaction make detailed in vivo analysis of embryo morphology more challenging at this developmental stage.

Figure 4.

In vivo OCM imaging of the oocyte, zygote, and preimplantation embryos in the oviduct reveals distinct cellular features consistent with those imaged in vitro (Media 5). All scale bars are 50 µm.

The capability for the presented imaging method to visualize cellular and subcellular structures of preimplantation embryos in vivo provides a range of opportunities in reproductive research. Particularly, defining the state of fertilization and distinguishing an unfertilized oocyte from a zygote brings the possibility of studying the timing and patterning of the mammalian fertilization in normal and pathological pregnancies, which has only been investigated in vitro and ex vivo [25]. Another exciting application of the described imaging method is associated with the observation that the thin layer of zona pellucida can be well resolved by OCM, both in vitro and in vivo. The function of zona pellucida and whether its shape is associated with cleavage planes are of particular interest [26–29]. In vivo OCM imaging could possibly be utilized to assist in such investigations. Observing the dynamic events within the cell, such as the nuclear fusion in the zygote, the cleavage process in early embryo, and analysis of embryonic development within the intact oviduct environment in mouse models linked to reproductive disorders might provide important functional insights into the role of the oviduct in preimplantation pregnancy and contribute to the understanding of unexplained cases of fertility failures.

Potentially, implementation of a laser source with broader bandwidth could improve OCM axial resolution toward isotropic spatial resolution in 3D. One challenge of in vivo OCM imaging is associated with the continuous movement of the oviduct due to smooth muscle contractions, which may create motion-induced distortion for 3D imaging, especially noticeable in the isthmus area. Therefore, one has to balance between the volumetric imaging rate, sampling density, and the size of the scan area, because reducing each of these parameters affects the quality of the acquired data. To overcome this limitation, potentially an ultrahigh-speed swept source OCT system [30] could be employed, which would allow for sufficiently faster volumetric imaging. Alternatively, for maintaining a high axial resolution, a supercontinuum laser source can be combined with a line scanning scheme for a high-speed spectral domain OCT system [31]. These systems could help to significantly reduce motion artifacts and might also be helpful to apply speckle reduction methods [32–34] that will ultimately improve the OCM imaging quality to resolve more detailed sub-cellular structures of preimplantation embryos.

In comparison with OCT, OCM has a higher transverse resolution, but the working distance as well as the depth of focus are significantly reduced. In regard to the limited working distance, for our in vivo setup, the imaging window can fit under the 10x scan lens; however, the flexibility to conduct imaging-guided manipulations, such as micro-injections, through the window aperture could potentially become compromised. Alternative approaches, e.g. injection through the skin from under the window, can be sought and may still be combined with OCM imaging. To overcome the reduced depth of focus, computational methods [35, 36] can be potentially applied to achieve a uniform resolution over the whole depth of view.

4. Conclusion

We present a method for in vivo imaging and staging of mouse preimplantation embryos using OCM through a dorsal imaging window. Characteristic morphological features of oocytes, zygotes, and preimplantation embryos can be well resolved through this approach both in vitro and in vivo. The comparable imaging quality of OCM with the traditional bright-field microscopy in vitro is presented. This approach brings numerous opportunities to study normal and pathological reproduction and preimplantation development in vivo, which can potentially contribute to investigation of female infertility and improvements of ART.

Supplementary Material

Media 1: In vitro OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse zygote at 0.5 dpc providing layer-by-layer cross-sectional visualizations.

Media 2: In vitro OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse preimplantation embryo at 1.5 dpc showing the cells in red and the zona pellucida in blue.

Media 3: In vitro OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse preimplantation embryo at late 2.5 dpc in which cross-sectional images cannot show all cells.

Media 4: In vitro OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse zygote at 0.5 dpc providing layer-by-layer cross-sectional visualizations.

Media 5: In vivo OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse preimplantation embryo at 1.5 dpc. The embryo inside the oviduct shows the two-cell state. For visibility purposes, the magenta channel is only shown for the oviduct lumen, which was manually segmented.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health with grants R01HL120140 and R01HD096335 (I.V.L.) and by the American Heart Association with grant 16POST30990070 (S.W.). We would like to thank Masha Larina for her assistance with illustration, Prof. Richard R. Behringer’s lab (the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) and Prof. Ross A. Poché’s lab (Baylor College of Medicine) for generous help with reagents.

Footnotes

Author biographies Please see Supporting Information online.

References

- [1].Niakan KK, Han J, Pedersen RA, Simon C, Pera RAR Development (Cambridge, England) 2012, 139, 829–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wang H, Dey SK Nature Reviews Genetics 2006, 7, 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fujimori T Development, Growth & Differentiation 2010, 52, 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sozen B, Can A, Demir N Developmental Biology 2014, 395, 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Marcho C, Cui W, Mager J Reproduction (Cambridge, England) 2015, 150, R109–R120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chazaud C, Yamanaka Y Development 2016, 143, 1063–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fauci LJ, Dillon R Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2006, 38, 371–394. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li S, Winuthayanon W Journal of Endocrinology 2017, 232, R1–R26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nguyen TH, Kandel ME, Rubessa M, Wheeler MB, Popescu G Nature Communications 2017, 8, 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Xiao J, Wang B, Lu G, Zhu Z, Huang Y Applied optics 2012, 51, 3650–3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zheng JG, Lu D, Chen T, Wang C, Tian N, Zhao F, Huo T, Zhang N, Chen D, Ma W, Sun JL, Xue P J Biomed Opt 2012, 17, 070503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zheng JG, Huo T, Chen T, Wang C, Zhang N, Tian N, Zhao F, Lu D, Chen D, Ma W, Sun JL, Xue P J Biomed Opt 2013, 18, 10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zarnescu L, Leung MC, Abeyta M, Sudkamp H, Baer T, Behr B, Ellerbee AK J Biomed Opt 2015, 20, 096004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Karnowski K, Ajduk A, Wieloch B, Tamborski S, Krawiec K, Wojtkowski M, Szkulmowski M Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Aguirre AD, Zhou C, Lee H-C, Ahsen OO, Fujimoto JG in Optical Coherence Microscopy, Vol. (Eds.: Drexler W, Fujimoto JG), Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015, pp.865–911. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Harms F, Latrive A, Boccara AC in Time Domain Full Field Optical Coherence Tomography Microscopy, Vol. (Eds.: Drexler W, Fujimoto JG), Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015, pp.791–812. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Burton JC, Wang S, Stewart CA, Behringer RR, Larina IV Biomed. Opt. Express 2015, 6, 2713–2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang S, Burton JC, Behringer RR, Larina IV Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 13216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang S, Larina IV Development 2018, 145, dev157685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang S, Syed R, Grishina OA, Larina IV Journal of Biophotonics 2018, 11, e201700316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Caligioni C Current protocols in neuroscience / editorial board, Crawley Jacqueline N. … [et al. ]. 2009, APPENDIX, Appendix-4I.

- [22].Piliszek A, Kwon GS, Hadjantonakis A-K Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.j.) 2011, 770, 243–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Behringer R, Gertsenstein M, Nagy KV, Nagy A, Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kidder BL Methods Mol Biol 2014, 1150, 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hino T, Muro Y, Tamura-Nakano M, Okabe M, Tateno H, Yanagimachi R Biology of reproduction 2016, 95, 50, 51-11-50, 51-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Modliński JA Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology 1970, 23, 539–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kurotaki Y, Hatta K, Nakao K, Nabeshima Y, Fujimori T Science 2007, 316, 719–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gardner RL Human Reproduction 2007, 22, 798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Alarcón VB, Marikawa Y Molecular reproduction and development 2008, 75, 1143–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang S, Singh M, Lopez AL, Wu C, Raghunathan R, Schill A, Li J, Larin KV, Larina IV Opt. Lett 2015, 40, 4791–4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Barrick J, Doblas ANA, Gardner MR, Sears PR, Ostrowski LE, Oldenburg AL Opt. Lett 2016, 41, 5620–5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kennedy BF, Hillman TR, Curatolo A, Sampson DD Opt. Lett 2010, 35, 2445–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang A, Xi J, Sun J, Li X Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 1721–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liba O, Lew MD, SoRelle ED, Dutta R, Sen D, Moshfeghi DM, Chu S, de la Zerda A Nature Communications 2017, 8, 15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Adie SG, Graf BW, Ahmad A, Carney PS, Boppart SA Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 7175–7180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liu Y-Z, South FA, Xu Y, Carney PS, Boppart SA Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 1549–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Media 1: In vitro OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse zygote at 0.5 dpc providing layer-by-layer cross-sectional visualizations.

Media 2: In vitro OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse preimplantation embryo at 1.5 dpc showing the cells in red and the zona pellucida in blue.

Media 3: In vitro OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse preimplantation embryo at late 2.5 dpc in which cross-sectional images cannot show all cells.

Media 4: In vitro OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse zygote at 0.5 dpc providing layer-by-layer cross-sectional visualizations.

Media 5: In vivo OCM volumetric imaging of the mouse preimplantation embryo at 1.5 dpc. The embryo inside the oviduct shows the two-cell state. For visibility purposes, the magenta channel is only shown for the oviduct lumen, which was manually segmented.