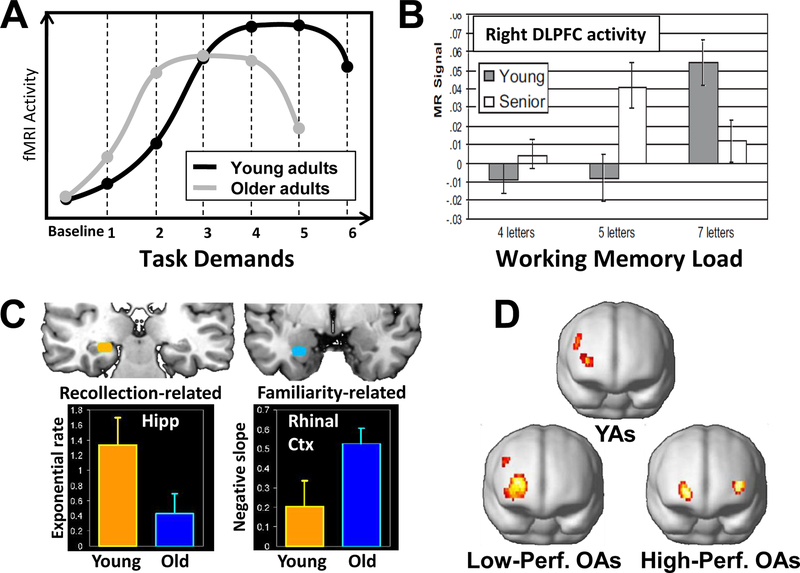

Figure 3. Compensation.

A. Hypothetical demand-activity function in young and old adults: as task demands increase activity first rises, then asymptotes, and finally declines. Because of reduced neural resources, this demand-activity function is shifted to the left in older adults, and hence they tend to show greater activity in the same regions as younger adults at lower levels of task difficulty (e.g., level 2) but lower activity at higher levels of task difficulty.82 B. Example of compensation by upregulation (consistent with the hypothetical function in panel A): in an fMRI study, older adults showed greater working memory activity in the right DLPFC than younger adults at lower levels of task demands (working memory load of 5 letters) but less activity at higher levels of task demands higher working memory load (working memory load of 7 letters, from REF.85) . C. Example of compensation by selection. This fMRI study compared age effects on the rich form of memory known as “recollection” and the less precise form of memory known as “familiarity,” measured in the same recognition memory task.86 Compared to younger adults, older adults showed reduced recollection-related activity in the hippocampus but increased familiarity-related activity in rhinal cortex . Thus, older adults compensated for deficits in an optimal but demanding process (recollection) by recruiting a suboptimal but less demanding process (familiarity). D. Example of compensation by reorganization. During an episodic memory retrieval task, young adults and low-performing older adults showed unilateral frontal activity whereas high-performing older adults showed bilateral frontal activity, suggesting a reorganization of the episodic retrieval network (from REF.87).