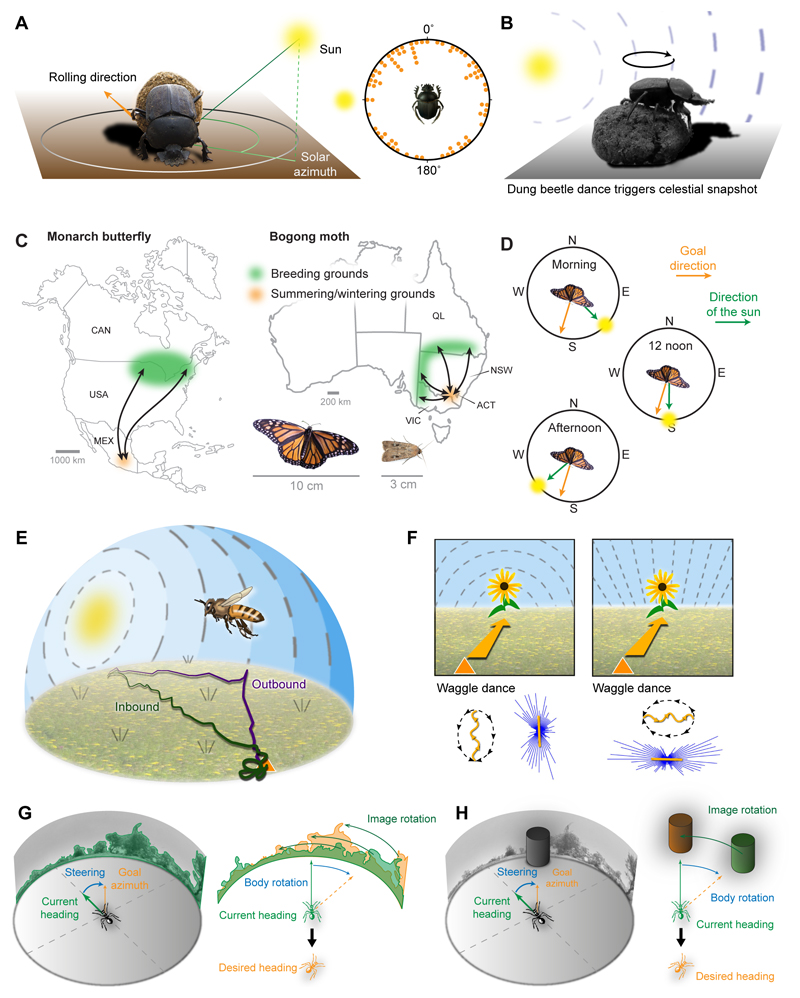

Fig. 2. Insect navigation behaviours.

(A) Ball-rolling dung beetles use celestial cues for choosing a random travel direction. Left: illustration of behaviour; right: rolling directions are random with respect to the Sun (data from Byrne et al., 2003). (B) During a circular dance on the dung ball these beetles take a snapshot of the celestial cue constellation to decide on a rolling direction. Beetle images in A/B courtesy of B. el Jundi and M. Dacke. (C) The Monarch butterfly and the Bogong moth migratory routes. Both insects fly over 1000 km from their breeding grounds to the wintering/summering sites. (D) When navigating by celestial cues, migrating insects need to compensate for the time of day. (E) A honeybee foraging flight with navigation-relevant visual cues used to compute a vector representation of the hive’s position (path integration). Triangle: hive. Looping pattern at the end of inbound flight: systematic search to locate nest entrance. Flight track adapted from Degen et al. (2016). (F) Skylight polarization is an ambiguous directional cue. Bees communicate their directional knowledge from the outbound flight (top panels) via the waggle dance (bottom panels). Dance distributions are bidirectional when only polarized light cues are available; adapted from Evangelista et al. (2014). (G) Image matching, as performed by ants in rich visual environments (Collett et al., 2013), is used for following habitual routes. A series of snapshots of the visual panorama are compared to current views and both are brought to a best match via body rotations (Zeil, 2012). (H) Landmark based navigation uses salient visual features independent of the surrounding panorama in a similar way to overall image matching. G/H adapted from Heinze, 2017.