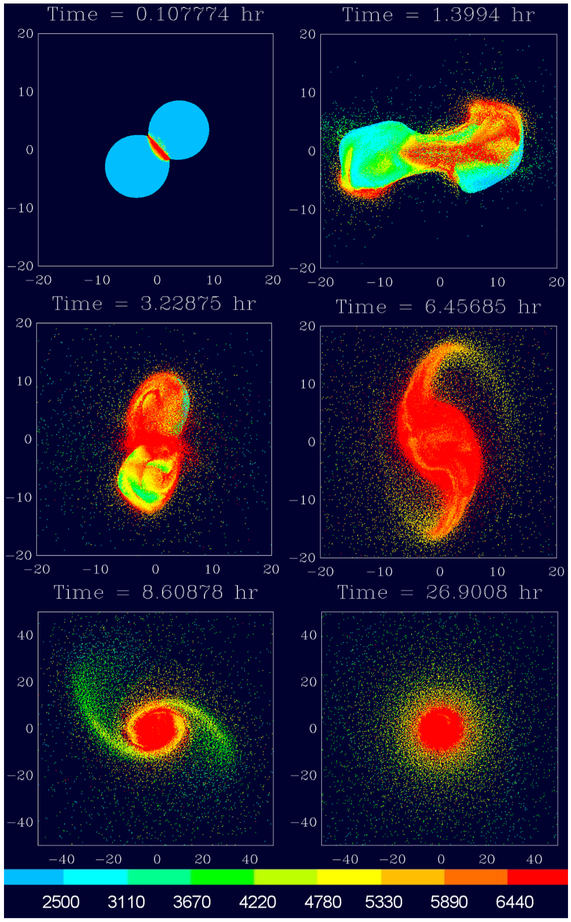

Figure 1.

An SPH simulation of a moderately oblique, low-velocity (v∞ = 4 km/sec) collision between an impactor and target with similar masses (run 31 from Table 1). Color scales with particle temperature in Kelvin, per color bar, with red indicating temperatures > 6440 K. All particles in the 3D simulation are overplotted. Time is shown in hours, and distances are shown in units of 103 km. After the initial impact, the planets re-collided, merged, and spun rapidly. Their iron cores migrated to the center, while the merged structure developed a bar-type mode and spiral arms (24). The arms wrapped up and finally dispersed to form a disk containing about 3 lunar masses whose silicate composition differed from that of the final planet by less than 1%. Due to the near symmetry of the collision, impactor and target material are distributed approximately proportionately throughout the final disk, so that the disk’s δfT value does not vary appreciably with distance from the planet.