Abstract

Insulin resistance is driven, in part, by activation of the innate immune system. We have discussed the evidence linking nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)1, an intracellular pattern recognition receptor, to the onset and progression of obesity-induced insulin resistance. On a molecular level, crosstalk between downstream NOD1 effectors and the insulin receptor pathway inhibits insulin signaling, potentially through reduced insulin receptor substrate action. In vivo studies have demonstrated that NOD1 activation induces peripheral, hepatic, and whole-body insulin resistance. Also, NOD1-deficient models are protected from high-fat diet (HFD)–induced insulin resistance. Moreover, hematopoietic NOD1 deficiency prevented HFD-induced changes in proinflammatory macrophage polarization status, thus protecting against the development of metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance. Serum from HFD-fed mice activated NOD1 signaling ex vivo; however, the molecular identity of the activating factors remains unclear. Many have proposed that an HFD changes the gut permeability, resulting in increased translocation of bacterial fragments and increased circulating NOD1 ligands. In contrast, others have suggested that NOD1 ligands are endogenous and potentially lipid-derived metabolites produced during states of nutrient overload. Nevertheless, that NOD1 contributes to the development of insulin resistance, and that NOD1-based therapy might provide benefit, is an exciting advancement in metabolic research.

Obesity, characterized by an abnormal increase in fat deposition, has been classified as the epidemic of the 21st century. The expansion of adipose tissue is accompanied by a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation, thereby inducing changes in proinflammatory cytokine secretion and promoting immune cell infiltration within adipose tissue (1, 2). The subsequent propagation of this inflammation to other metabolically active tissues, a process termed “metabolic inflammation” or “metaflammation,” is now understood as a primary mediator of the onset of insulin resistance (3, 4). Although the mechanisms linking obesity-induced inflammation and the development of insulin resistance are still unclear, the innate immune system (discussed in the next section) is currently being investigated as a key driving factor.

Innate Immune System

The innate immune system is the body’s first line of defense against invading pathogens, consisting of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which provide the basis for acute immune function. PRRs are critical members of the innate immune system owing to their ability to identify conserved molecular patterns common to all foreign invaders [pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)] and, subsequently, activate downstream inflammatory responses (5, 6). This class of receptors is primarily expressed in innate immune cells (i.e., monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, eosinophils) and some nonimmune cells, such as epithelial cells, which often come into contact with exogenous microbes, although some PRRs can be ubiquitously expressed. In addition to PAMPs, PRRs detect danger signals, such as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which can be of exogenous or endogenous origin (7).

Three prominent subclasses of PRRs include membrane-bound toll-like receptors (TLRs), intracellular nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) receptors, and NOD-like receptors that form inflammasomes. In contrast to NOD-like receptor forming inflammasomes, which, once stimulated, induce an acute cytokine-release response, NODs and TLRs signal via transcriptional-mediated inflammatory responses (8).

Notably, evidence has emerged that heightened activation of the innate immune system can contribute to the development and progression of metabolic disease (9). In the present report, we have discussed how activation of a specific PRR, NOD1, in metabolically active and systemic tissues can induce peripheral, hepatic, and whole-body insulin resistance. We have also outlined the potential cellular signaling pathways responsible for mediating insulin resistance and the proposed theories driving NOD1 activation in vivo.

Nucleotide Binding Oligomerization Domain-1

NOD1 belongs to the NOD-like receptor family, which consists of PRRs that reside in the cytoplasm of cells (10, 11). NOD1 is ubiquitously expressed and recognizes bacterial peptidoglycan fragments, including d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid found in gram-negative and some gram-positive bacteria (10–12). Structurally, NOD1 contains three domains: an N-terminal caspase recruitment domain responsible for mediating downstream inflammatory signaling cascades, a nucleotide binding domain necessary for receptor oligomerization and activation, and a leucine-rich C-terminal region that recognizes conserved microbial patterns and ligands (10, 12).

How NOD1 Activation Leads to the Onset of Insulin Resistance—A Cellular Perspective

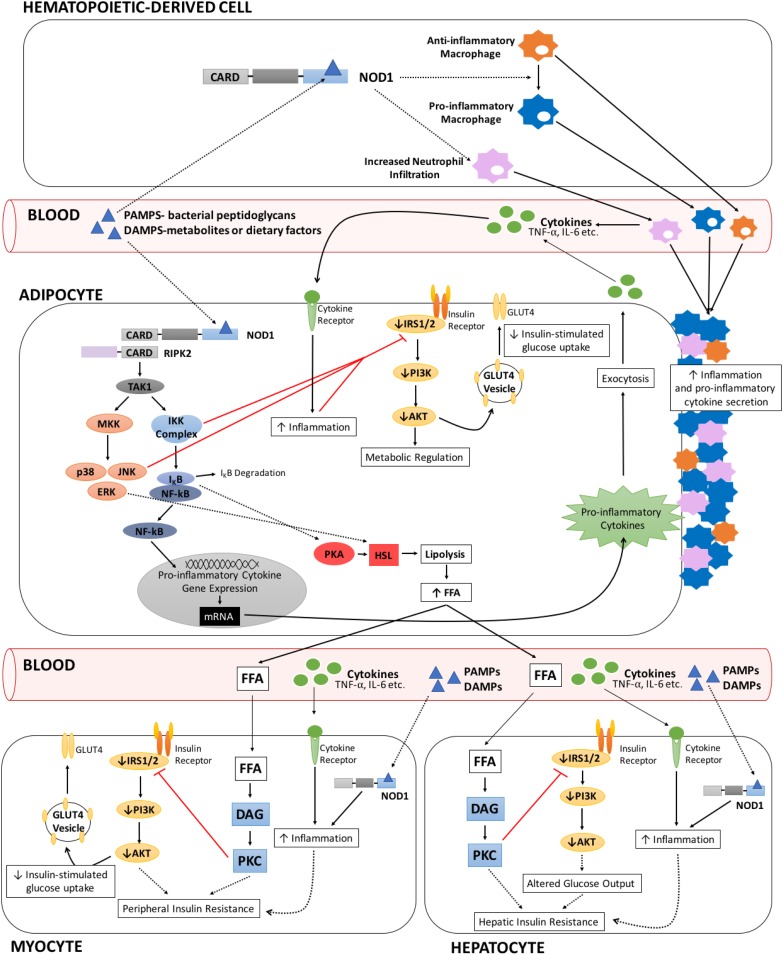

On interaction with its ligands, NOD1 self-oligomerizes to acquire an active conformation that elicits downstream signaling of proinflammatory and stress pathways (13, 14). The adaptor protein receptor-interacting protein kinase-2 (RIPK2) interacts with the caspase recruitment domain motif of NOD1 and subsequently recruits the kinase TAK1 as a prerequisite to activate nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and MAPK signaling (13–16) (Fig. 1). The NF-κB and MAPK cascades integrate signaling by NOD1, NOD2, and other innate immune complexes such as TLRs and various inflammasomes to vary the intensity, duration, and pattern of the downstream outcomes. NOD1 signaling can potentiate or be additive to that of TLR4 (7, 17).

Figure 1.

Proposed sources of NOD1 activation and corresponding physiologic, endocrine, and cell tissue communication events leading to insulin resistance in different tissues. Generic NOD1 activation by bacterial peptidoglycans (PAMPs) or metabolites (DAMPs) initiate a downstream inflammatory signal cascade in which the adaptor protein, RIPK2, interacts with NOD1 via its caspase recruitment domain (CARD) motif. Subsequent recruitment and activation of TAK1 enhances MAPK and NF-κB signaling. Crosstalk between the insulin receptor pathway and both NF-κB and MAPK signaling can occur through inhibitory inputs of IKKβ and JNK on IRS1,2 phosphorylation, reducing insulin signaling and, thus, contributing to insulin resistance. Circulating proinflammatory cytokines—NF-κB signaling promoted proinflammatory cytokine gene and protein expression, establishing a feed-forward cascade in which cytokines can bind to their respective receptors and propagate downstream inflammatory signaling on the same, neighbor, or distal cell. Enhanced inflammation in target cells attenuates insulin receptor signaling, thereby participating in the onset of whole-body insulin resistance. NOD1 signaling in cells of hematopoietic origin amplifies peripheral inflammation and insulin resistance—NOD1 activation in hematopoietic cells promotes changes in macrophage polarization, converting anti-inflammatory macrophages to a proinflammatory state. Elevated proinflammatory cytokine secretion and increased proinflammatory macrophage infiltration in adipose and peripheral tissues results in heightened inflammation in target tissues and corresponding reductions in insulin signaling. The NOD1-dependent influx in proinflammatory macrophages is accompanied by an increase in neutrophil infiltration, which together are thought to participate in inflammation-mediated insulin resistance. NOD1 signaling in adipose tissue stimulates lipolysis and reduces insulin-stimulated glucose uptake—increased inflammation and cytokine secretion in adipose tissue as a result of autonomous activation of NOD1 and infiltration of immune cells collectively dampen insulin receptor signaling. Loss of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT activity translates to reduced GLUT4 membrane translocation, thereby decreasing insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. NOD1-induced inflammation also enhances adipose lipolysis via proposed NF-κB/PKA– and ERK-dependent pathways, increasing hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) activity. Elevated circulating FFAs travel to, and accumulate in, metabolically active tissues, where they can convert into lipid metabolites and stimulate PKC isoforms. Enhanced PKC signaling in the liver and muscle mediates changes in local insulin receptor signaling, contributing to the onset of hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance, respectively. However, NOD1 activation might also occur directly in liver and skeletal muscle.

NF-κB signaling and inhibition of insulin receptor signal transduction

A major outcome of NF-κB pathway activation is the increased expression of cytokines and proinflammatory factors necessary for generating an immune response (18). In particular, the NF-κB complex controls the transcription of some cytokine genes such as IL1β, IL6, TNFA, and CXCL8 and several others (19, 20). In unstimulated cells, the IκB inhibitor proteins bind and hold the NF-κB complex within the cytoplasm, restricting nuclear localization of the transcription factor belonging to the p65/RelA subunit of the NF-κB complex (3, 18). With innate immune receptor activation, phosphorylation of the IKK complex induces IκB ubiquitination and degradation, liberating the p65 subunit of NF-κB for nuclear translocation and stimulation of target gene expression (3, 18).

NF-κB downstream signals often interact with other signaling pathways, including the insulin receptor cascade, buttressing the concept that NF-κB–induced inflammation partakes in the development of insulin resistance. Mechanistically, the activated IKK complex targets and phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate (IRS) at various serine residues, which attenuates downstream signal transmission (21, 22) (Fig. 1). NF-κB signaling also upregulates PTP-1B, a tyrosine phosphatase that dephosphorylates tyrosine residues on IRS-1, thereby dampening downstream insulin signaling (23). The link between NF-κB signaling and insulin resistance has been further elucidated in IKK and NF-κB rodent knockout models, which have demonstrated that global inhibition of the NF-κB pathway preserves peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity after high-fat diet (HFD) feeding (24–26). In further support, tissue-specific IKK models have helped to decipher the key tissues involved in NF-κB–dependent insulin resistance. Hepatocyte-specific IKKβ deficiency protects against the development of HFD-induced hepatic insulin resistance but fails to preserve peripheral insulin action (27, 28). In contrast, myeloid-specific IKKβ knockout models have maintained whole-body insulin sensitivity, including insulin action in both the liver and the muscle tissues (27). These results have validated the relationship between inflammation and maintenance of metabolic control and have highlighted that NF-κB signaling in the liver and immune cells largely contribute to impaired whole-body insulin action. However, little evidence has linked NF-κB pathway activation in muscle and adipose tissue to aberrant insulin action. NF-κB activity in muscle might not participate at all in obesity-induced insulin resistance (29).

The contribution of NF-κB activity to insulin signaling is not only cell autonomous but can also become paracrine and, even, endocrine, given that activation of NF-κB signaling in vivo results in an increase in circulating proinflammatory cytokines. Because cytokines act in a number of cells and tissues to activate NF-κB, this generates a feed-forward proinflammatory loop, such that cytokines can continuously bind to their respective receptors and propagate downstream NF-κB signaling (3, 4). Consequently, feed-forward attenuation of insulin signaling often occurs (Fig. 1). Cytokines also act through the JAK/STAT pathway to increase expression of SOCS proteins, which target and reduce IRS tyrosine phosphorylation and promote IRS degradation (3, 4, 30–32).

Heightened MAPK signaling attenuates IRS

In addition to NF-κB, NOD1 receptor activation is coupled to MAPK signaling; primarily ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK activity (13, 14, 33). The three MAPKs collectively participate in the development and progression of insulin resistance, predominantly through serine phosphorylation of IRS, although other mechanisms might also be involved (21, 34–37) (Fig. 1). Rodent knockout models have been studied extensively to explore JNK’s role in the metabolic regulation of insulin resistance. Global JNK-1–deficient mice are protected from HFD-induced insulin resistance (25, 38, 39), and conditional JNK1 knockout models in adipose and skeletal muscle tissue have demonstrated improved whole-body (40, 41) and peripheral insulin sensitivity (42), respectively. In contrast, and perhaps unexpectedly, ablation of JNK1 in hepatocytes enhances glucose-intolerant and insulin-resistant phenotypes, providing evidence that JNK1 activity, in part, sustains insulin action in the liver (43). Overall, these models have validated the relationship between inflammation and insulin resistance, and, more specifically, how overactivation of JNK-dependent signaling, with the exception of hepatocyte JNK, induces whole-body insulin resistance.

NOD1 Gene Expression Is Upregulated in Conditions of Metabolic Dysregulation

Although ubiquitously expressed, NOD1 levels are more abundant in immune cells, the gastrointestinal tract, and adipose tissue (44–46). Previous evidence has suggested that NOD1 gene expression and activity are upregulated in some tissues after increased energy consumption and prolonged HFD feeding. For example, NOD1 mRNA expression was significantly greater in the subcutaneous fat and isolated adipocytes of HFD-induced obese mice compared with control diet-fed mice (47, 48). Furthermore, human subjects with metabolic syndrome and gestational diabetes have shown significantly greater NOD1 activity and mRNA expression in adipose tissue compared with control subjects with normal glucose tolerance (49, 50). Also, NOD1 expression correlated with the patients’ homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), HbA1c levels, and waist circumference (50). NOD1 mRNA levels were also upregulated in the immune cells of individuals with type 2 diabetes (51) and positively correlated with HOMA-IR, HbA1c, and fasting and postprandial plasma glucose levels (51). Such evidence of increased NOD1 gene expression in the adipocytes and immune cells of patients with metabolic disorders, along with the corresponding changes in insulin sensitivity and glucose control, highlight that NOD1 and its downstream-mediated inflammatory responses might contribute to metabolic dysregulation and the onset of obesity-induced insulin resistance. Furthermore, polymorphisms of the human Nod1 gene have been correlated with fat-induced changes in insulin sensitivity, such that individuals with Nod1 variants consuming excess dietary fat had increased HOMA-IR compared with those consuming similar diets lacking the genetic variant, implying that NOD1 is responsive to lipids and drives subsequent changes in insulin sensitivity (52). However, obesity- and diabetes-derived changes in NOD1 mRNA expression found in adipocytes and immune cells have yet to be reported in other metabolically active or systemic tissues.

Evidence of NOD1-Dependent Insulin Resistance

The first connection between NOD1 and insulin resistance was presented by Schertzer et al. (44) showing that NOD1/2 double-knockout mice are protected from developing HFD-induced insulin intolerance and by Amar et al. (53), showing a similar protection in NOD1-deficient mice (53). In contrast, NOD2-deficient mice were not protected and even showed accentuation of HFD-induced insulin intolerance (54). Directly linking NOD1 activation in vivo to the onset and progression of insulin resistance, exogenous NOD1 ligand injection in mice resulted in the acute development of peripheral and hepatic insulin resistance. This was evidenced by the results from hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp experiments and direct demonstration of impaired insulin signaling in both skeletal muscle and liver (44).

NOD1 sensing in adipocytes and progression of cell-autonomous insulin resistance

3T3-L1 adipocytes and isolated human adipocytes have been used to study how NOD1 activation influences insulin signaling and glucose uptake. Exposing adipocytes to NOD1 ligands enhanced NF-κB and MAPK signaling and amplified proinflammatory cytokine gene expression (47, 48). Furthermore, NOD1 activation in adipocytes suppressed insulin receptor signaling, as demonstrated by reduced Akt and IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, and increased IRS-1 serine phosphorylation (47, 48). As a result of NOD1-dependent attenuation of insulin receptor signaling, insulin stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes was also reduced but was restored by NOD1 targeting small interfering RNA (siRNA) (47, 48, 55), suggesting a link between NOD1-mediated inflammation and the onset of peripheral insulin resistance (Fig. 1).

Another outcome of NOD1 activation, one especially relevant to the onset of whole-body insulin resistance (discussed in the next section), is the stimulation of adipocyte lipolysis (56). NOD1-mediated lipolysis involves ERK-, PKA-, and NF-κB–dependent pathways, all of which induce phosphorylation of lipolytic targets such as hormone-sensitive lipase (57, 58) (Fig. 1). Some have even proposed that PKA activation is a result of NF-κB pathway stimulation, evidenced by NF-κB inhibitors attenuating PKA-dependent phosphorylation of hormone sensitive lipase (56). Additionally, PKA has been reported to phosphorylate and activate NF-κB p65 (59, 60).

NOD1 sensing in immune cells and its contribution to whole-body insulin resistance

Obesity triggers an influx of infiltrating immune cells—most will be monocytes, but also neutrophils and lymphocyte lineages—to adipose and other metabolically active tissues, resulting largely in an increase in local monocyte-derived macrophages (61). Obesity and HFD feeding initiate a phenotypic switch in infiltrating and local macrophages from an anti-inflammatory/tissue repair orientation to a proinflammatory orientation (62, 63). The abundance of proinflammatory adipose and muscle tissue macrophages has been correlated with the progression of insulin resistance (62, 64). In contrast, the extent of an anti-inflammatory orientation of macrophages in the muscle of humans with a spectrum of metabolic diseases has correlated with improved insulin sensitivity (65). Mechanistically, it is thought that cytokines produced locally by the activated macrophages during HFD and obesity intersect with insulin signaling in adipose, muscle, and liver tissue, provoking insulin resistance within these metabolically active tissues. Additionally, cytokines emitted locally reach the circulation and contribute to insulin resistance in distal tissues.

Given that NOD1 is expressed at high levels in immune cells, it has been of interest to investigate the role of NOD1 in immune cell infiltration and macrophage polarization and the contribution of NOD1 in these cells to insulin resistance. Thus, Chan et al. (17) designed a hematopoietic cell-specific NOD1 knockout model by transplanting bone marrow from NOD1-deficient mice into wild-type mice. With HFD feeding, hematopoietic NOD1-deficient mice presented with improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity and reduced adipose tissue inflammation compared with the HFD-fed control mice receiving bone marrow from wild-type mice (17). Insulin action in the tissues at the level of Akt phosphorylation was also improved. Mice with NOD1-deficient immune cells did not have fewer macrophages localized in adipose tissue compared with the HFD-fed control mice, but rather, these macrophages failed to turn proinflammatory (17). This change was accompanied by a reduction in neutrophil count in the tissue, in accordance with recent evidence of a neutrophil contribution to insulin resistance (66, 67) (Fig. 1).

Collectively, these results support the notion that immune cell-derived NOD1 activation, not only promotes macrophage proinflammatory polarization in adipose tissue, but also influences whole-body metabolic profiles by contributing to the development of insulin resistance.

NOD1-Mediated Adipocyte Lipolysis and Whole-Body Insulin Resistance

As previously stated, in vitro data have suggested that NOD1-dependent signaling can enhance basal adipocyte lipolysis, thereby potentially increasing circulating free fatty acids (FFAs). FFAs, when in abundance, drive ectopic lipid accumulation and act as key signaling molecules responsible for impaired insulin action. In metabolically active tissues, FFAs can convert into lipid metabolites such as diacylglycerol (DAG) and long-chain acyl- coenzyme A, which proceed to activate protein kinase C (PKC) and other downstream effector molecules (68, 69). Various PKC isoforms phosphorylate and negatively regulate IRS-1, providing a potential, direct cellular mechanism for the onset of whole-body insulin resistance (70–73). In accordance with the lipid metabolites theory, NOD1-dependent lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes resulted in DAG accumulation and downstream PKC-δ activation (58). Furthermore, in vivo activation of the FFA/DAG/PKC axis in insulin-sensitive tissues, such as the liver and skeletal muscle, results in the development of hepatic insulin resistance and peripheral insulin resistance, respectively (74–78). Together, these results suggest that NOD1-mediated adipocyte lipolysis and subsequent propagation of FFA to metabolically active tissues might participate in the onset of whole-body insulin resistance (Fig. 1).

Heightened immune cell infiltration and proinflammatory cytokine secretion in adipose tissue also take part in adipocyte lipolysis and progression of whole-body insulin resistance. In line with previous discussions that NOD1 activation in immune cells promotes proinflammatory macrophage polarization and enhanced cytokine secretion in adipose tissue, it is now well recognized that proinflammatory cytokines, primarily TNF-α and IL-6, stimulate adipocyte lipolysis (79–81). By highlighting that NOD1-dependent inflammation drives adipocyte lipolysis and a consequent flux in circulating FFAs, these results provide an alternative mechanism by which NOD1 activation might lead to whole-body insulin resistance. To further support the relationship between inflammation, NOD1-mediated lipolysis, and whole-body insulin resistance, it is possible that NOD1-induced lipolysis might directly signal adipose tissue macrophage infiltration (82) and enhanced proinflammatory cytokine expression (58). Thus, an aggressive feed-forward loop transpires such that NOD1-dependent cytokine secretion and NOD1-dependent adipocyte lipolysis stimulate one another and, collectively, drive the onset of whole-body insulin resistance. Finally, lipid intermediates generated from NOD1-stimulated lipolysis have also been shown to enhance inflammation via PKC-δ activation of IL-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) 1/4 (58). IRAKs are known mediators of IL-1 receptor signaling, including activation of NF-κB and JNK.

In summary, NOD1-stimulated lipolysis in adipocytes might induce a state of whole-body insulin resistance via both activation of the FFA/DAG/PKC axis in metabolically active tissues and heightened inflammatory responses through enhanced cytokine secretion and IRAK signaling. This hypothesis awaits support from in vivo data from adipocyte-specific NOD1 knockout mice. Alternatively, or in addition, NOD1 activation in hepatocytes and myocytes might contribute to the insulin resistance state as suggested by in vitro data using NOD1 activators (44) (Fig. 1).

NOD1 Activation In Vivo

A paramount question, still open, is the identity of the circulating and possibly in situ factors that drive the activation of NOD1 in obesity, whether they are PAMPs (microbiota-released factors) or DAMPs (metabolites or dietary factors), or both. It is also important to determine whether NOD1 acts in synergy with the input of circulating cytokines.

HFD feeding changes gut permeability and promotes PAMP-derived NOD1 activation

One theory to explain the onset of NOD1 signaling in metabolically active and systemic tissues is that the HFD-associated increase in intestinal permeability allows for a low-level translocation of bacteria and bacterial fragments from the gut into the systemic circulation to act as ligands for NOD1 receptors (17). This modest influx of endotoxins, derived mostly from gram-negative bacteria, in metabolically active tissues has been commonly referred to as “metabolic endotoxemia” (83).

The relationship between HFD feeding and changes in the gastrointestinal microbiota is well-established. Intestinal bacterial profiling of mice in some studies have shown an increased gram-negative/gram-positive ratio (84). These diet-induced changes in intestinal bacterial populations appear to be accompanied by modifications in gut permeability or at least in some of the morphological features of the gut associated with increased permeability (83–85). An early study reported that mice fed an HFD for as few as 4 weeks had increased plasma endotoxin concentrations relative to mice fed a control diet owing to enhanced intestinal leakiness (84). Histologically, the gut of these HFD-fed mice showed reduced intestinal epithelial tight junction protein (occludin and ZO-1) expression, and the mRNA levels correlated negatively with circulating endotoxin concentrations. These findings have driven the hypothesis that HFD enhances intestinal permeability via reduced tight junction function (84). A green fluorescent protein-labeled Escherichia coli fed by gavage into mice was detected, as was its DNA, in blood, adipose tissue, and lymph nodes of mice fed an HFD for 4 weeks (53).

From these findings, one could propose that the influx of diverse PAMPs, including NOD1 ligands, might also occur. At 18 weeks of HFD feeding in mice, elevated circulating NOD1 activators (detected on a cell culture reporting assay) and the extent of these NOD1 activators correlated with increased fasting blood glucose levels (17). Further research must be conducted to determine the molecular identity of the activators.

NOD1 in the gut might also have a direct role in facilitating bacterial translocation. Unlike wild-type mice, NOD1 knockout mice did not have elevated circulating bacterial DNA when fed an HFD (53). These results imply that NOD1 activation contributes to the onset of HFD-induced bacterial translocation originating in the intestine and the subsequent inflammatory responses.

Recognition of metabolites as DAMPs during conditions of nutrient overload and subsequent NOD1 activation

In states of chronic overfeeding, it has been proposed that excess nutrients can be recognized as harmful moieties and, therefore, will act as DAMPs (25). In particular, lipids are currently under consideration as potential DAMPs and mediators of NOD1 activation and inflammation-derived insulin resistance. Given that saturated fats are a major component of HFDs and that circulating saturated fatty acids are elevated in individuals who are obese, the role of saturated fatty acids in NOD1 activation has been examined. In vitro studies showed that saturated fatty acids induced NOD1-mediated effects in colonic cells, and siRNA-mediated NOD1 knockdown attenuated saturated fatty acid-induced inflammatory responses (86). Additionally, saturated fatty acids decreased insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes; however, siRNA targeting of NOD1 partially recovered the insulin response (87). Although these results are promising, very little research has been performed in vivo to investigate the relationship between saturated fat-dependent NOD1 activation and the development of insulin resistance. Other potential DAMP-derived NOD1 activators, in addition to saturated fat, might provide important contributions to this process. However, the existing data implicating NOD1 in insulin resistance were obtained using HFDs. It is possible that, whether due to lipid-derived DAMPs or intestinal absorption of PAMPs, the obesity induced by high saturated fat diets might have a greater effect on NOD1 activation than obesity induced by general nutrient excess.

Pharmacological Relevance—Suppression of NOD1-Induced Insulin Resistance

The results from initial studies suggested that pharmacological inhibition of NOD1 signaling had beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity. In particular, tyrosine kinase inhibitors used in cancer therapy have been of interest because they attenuate downstream NF-κB signaling (88) and might, therefore, help relieve the metabolic inflammation elicited by a number of upstream pathways. More specifically, a subset of tyrosine kinase inhibitors that target RIPK2 restored NOD1-induced suppression of insulin signaling and prevented NOD1-induced lipolysis in adipocytes (88). Furthermore, the preadministration of RIPK2 inhibitors to mice prevented NOD1-dependent glucose intolerance, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced overall inflammation and macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue (88). Further studies are required to generalize these findings in the diverse conditions of obesity and, ideally, using more specific RIPK2 inhibitors (89, 90). Various groups have also derived small molecules that selectively target NOD1; however, these have not been studied in the context of metabolic disease (91, 92). Perhaps, therapies that directly target NOD1 would be more beneficial than RIPK2 inhibitors, because NOD2 signaling would remain intact. The anti-inflammatory properties of NOD1-based therapies might provide a breakthrough therapy toward treating obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance because they are potentially less immunosuppressive than other anti-inflammatory therapies (93).

Conclusions

NOD1 activation is emerging as one bridge between obesity-induced inflammation and the development of insulin resistance. Crosstalk among NOD1, downstream NF-κB, and MAPK signaling and the insulin receptor pathway exists and can lead to inhibition of insulin signaling, predominantly via reduced IRS action. Although discerning whether NOD1 is activated by PAMPs that translocate across the intestinal barrier or by lipid-derived DAMPs requires further investigation, it has, nonetheless, been established that NOD1 activation in vivo contributes to the progression of peripheral, hepatic, and whole-body insulin resistance.

Acknowledgments

We recognize all the work that has been conducted on this topic and the contribution to this work by Dr. Dana J. Philpott. We recognize Kenny L. Chan, Theresa Tam, and Parastoo Boroumand for their contribution to some of the studies from our groups cited in the present report.

Financial Support: The present study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grants MOP 69018 and PJT 153032 to A.G. and Grant FND 143203 to A.K.). S.L.R. was supported by a Banting and Best Diabetes Centre-Novo Nordisk Scholarship.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- FFA

free fatty acid

- HFD

high-fat diet

- HOMA-IR

homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

- IRAK

IL-1 receptor associated kinase

- IRS

insulin receptor substrate

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- NOD

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PPR

pattern recognition receptor

- RIPK2

receptor-interacting protein kinase-2

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TLR

toll-like receptor

References

- 1. Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xu H. Obesity and metabolic inflammation. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2013;10(1-2):21–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen L, Chen R, Wang H, Liang F. Mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:508409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dali-Youcef N, Mecili M, Ricci R, Andrès E. Metabolic inflammation: connecting obesity and insulin resistance. Ann Med. 2013;45(3):242–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by the innate immune system. Int Rev Immunol. 2011;30(1):16–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Medzhitov R, Janeway CA Jr. Decoding the patterns of self and nonself by the innate immune system. Science. 2002;296(5566):298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tang D, Kang R, Coyne CB, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT. PAMPs and DAMPs: signal 0s that spur autophagy and immunity. Immunol Rev. 2012;249(1):158–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oviedo-Boyso J, Bravo-Patiño A, Baizabal-Aguirre VM. Collaborative action of Toll-like and NOD-like receptors as modulators of the inflammatory response to pathogenic bacteria. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:432785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pickup JC, Crook MA. Is type II diabetes mellitus a disease of the innate immune system? Diabetologia. 1998;41(10):1241–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Correa RG, Milutinovic S, Reed JC. Roles of NOD1 (NLRC1) and NOD2 (NLRC2) in innate immunity and inflammatory diseases. Biosci Rep. 2012;32(6):597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moreira LO, Zamboni DS. NOD1 and NOD2 signaling in infection and inflammation. Front Immunol. 2012;3:328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):240–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caruso R, Warner N, Inohara N, Núñez G. NOD1 and NOD2: signaling, host defense, and inflammatory disease. Immunity. 2014;41(6):898–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Strober W, Murray PJ, Kitani A, Watanabe T. Signalling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(1):9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kobayashi K, Inohara N, Hernandez LD, Galán JE, Núñez G, Janeway CA, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. RICK/Rip2/CARDIAK mediates signalling for receptors of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Nature. 2002;416(6877):194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nembrini C, Kisielow J, Shamshiev AT, Tortola L, Coyle AJ, Kopf M, Marsland BJ. The kinase activity of Rip2 determines its stability and consequently Nod1- and Nod2-mediated immune responses. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(29):19183–19188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan KL, Tam TH, Boroumand P, Prescott D, Costford SR, Escalante NK, Fine N, Tu Y, Robertson SJ, Prabaharan D, Liu Z, Bilan PJ, Salter MW, Glogauer M, Girardin SE, Philpott DJ, Klip A. Circulating NOD1 activators and hematopoietic NOD1 contribute to metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance. Cell Reports. 2017;18(10):2415–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baker RG, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-κB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011;13(1):11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1(4):a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18(49):6853–6866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boura-Halfon S, Zick Y. Phosphorylation of IRS proteins, insulin action, and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(4):E581–E591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gao Z, Hwang D, Bataille F, Lefevre M, York D, Quon MJ, Ye J. Serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 by inhibitor kappa B kinase complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(50):48115–48121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zabolotny JM, Kim YB, Welsh LA, Kershaw EE, Neel BG, Kahn BB. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B expression is induced by inflammation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(21):14230–14241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chiang SH, Bazuine M, Lumeng CN, Geletka LM, Mowers J, White NM, Ma JT, Zhou J, Qi N, Westcott D, Delproposto JB, Blackwell TS, Yull FE, Saltiel AR. The protein kinase IKKepsilon regulates energy balance in obese mice. Cell. 2009;138(5):961–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tanti JF, Ceppo F, Jager J, Berthou F. Implication of inflammatory signaling pathways in obesity-induced insulin resistance. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;3:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zeng T, Zhou J, He L, Zheng J, Chen L, Wu C, Xia W. Blocking nuclear factor-kappa B protects against diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, Maeda S, Li ZW, Long JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Poli G, Olefsky J, Karin M. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005;11(2):191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cai D, Yuan M, Frantz DF, Melendez PA, Hansen L, Lee J, Shoelson SE. Local and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-beta and NF-kappaB. Nat Med. 2005;11(2):183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Röhl M, Pasparakis M, Baudler S, Baumgartl J, Gautam D, Huth M, De Lorenzi R, Krone W, Rajewsky K, Brüning JC. Conditional disruption of IkappaB kinase 2 fails to prevent obesity-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(3):474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(2):98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29(1):415–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim JH, Bachmann RA, Chen J. Interleukin-6 and insulin resistance. Vitam Horm. 2009;80:613–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Allison CC, Kufer TA, Kremmer E, Kaparakis M, Ferrero RL. Helicobacter pylori induces MAPK phosphorylation and AP-1 activation via a NOD1-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2009;183(12):8099–8109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aguirre V, Uchida T, Yenush L, Davis R, White MF. The c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase promotes insulin resistance during association with insulin receptor substrate-1 and phosphorylation of Ser(307). J Biol Chem. 2000;275(12):9047–9054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fujishiro M, Gotoh Y, Katagiri H, Sakoda H, Ogihara T, Anai M, Onishi Y, Ono H, Funaki M, Inukai K, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Oka Y, Asano T. MKK6/3 and p38 MAPK pathway activation is not necessary for insulin-induced glucose uptake but regulates glucose transporter expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(23):19800–19806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fujishiro M, Gotoh Y, Katagiri H, Sakoda H, Ogihara T, Anai M, Onishi Y, Ono H, Abe M, Shojima N, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Oka Y, Asano T. Three mitogen-activated protein kinases inhibit insulin signaling by different mechanisms in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(3):487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tanti JF, Jager J. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance: role of stress-regulated serine kinases and insulin receptor substrates (IRS) serine phosphorylation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9(6):753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Görgün CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature. 2002;420(6913):333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sabio G, Davis RJ. cJun NH2-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1): roles in metabolic regulation of insulin resistance. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(9):490–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sabio G, Das M, Mora A, Zhang Z, Jun JY, Ko HJ, Barrett T, Kim JK, Davis RJ. A stress signaling pathway in adipose tissue regulates hepatic insulin resistance. Science. 2008;322(5907):1539–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang X, Xu A, Chung SK, Cresser JH, Sweeney G, Wong RL, Lin A, Lam KS. Selective inactivation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase in adipose tissue protects against diet-induced obesity and improves insulin sensitivity in both liver and skeletal muscle in mice. Diabetes. 2011;60(2):486–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sabio G, Kennedy NJ, Cavanagh-Kyros J, Jung DY, Ko HJ, Ong H, Barrett T, Kim JK, Davis RJ. Role of muscle c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1 in obesity-induced insulin resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(1):106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sabio G, Cavanagh-Kyros J, Ko HJ, Jung DY, Gray S, Jun JY, Barrett T, Mora A, Kim JK, Davis RJ. Prevention of steatosis by hepatic JNK1. Cell Metab. 2009;10(6):491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schertzer JD, Tamrakar AK, Magalhães JG, Pereira S, Bilan PJ, Fullerton MD, Liu Z, Steinberg GR, Giacca A, Philpott DJ, Klip A. NOD1 activators link innate immunity to insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2011;60(9):2206–2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tamrakar AK, Schertzer JD, Chiu TT, Foley KP, Bilan PJ, Philpott DJ, Klip A. NOD2 activation induces muscle cell-autonomous innate immune responses and insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2010;151(12):5624–5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhao L, Hu P, Zhou Y, Purohit J, Hwang D. NOD1 activation induces proinflammatory gene expression and insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301(4):E587–E598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou YJ, Zhou H, Li Y, Song YL. NOD1 activation induces innate immune responses and insulin resistance in human adipocytes. Diabetes Metab. 2012;38(6):538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lappas M. NOD1 expression is increased in the adipose tissue of women with gestational diabetes. J Endocrinol. 2014;222(1):99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhou YJ, Liu C, Li CL, Song YL, Tang YS, Zhou H, Li A, Li Y, Weng Y, Zheng FP. Increased NOD1, but not NOD2, activity in subcutaneous adipose tissue from patients with metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(7):1394–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shiny A, Regin B, Balachandar V, Gokulakrishnan K, Mohan V, Babu S, Balasubramanyam M. Convergence of innate immunity and insulin resistance as evidenced by increased nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD) expression and signaling in monocytes from patients with type 2 diabetes. Cytokine. 2013;64(2):564–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cuda C, Badawi A, Karmali M, El-Sohemy A. Effects of polymorphisms in nucleotide-binding oligomerization domains 1 and 2 on biomarkers of the metabolic syndrome and type II diabetes. Genes Nutr. 2012;7(3):427–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Amar J, Chabo C, Waget A, Klopp P, Vachoux C, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Smirnova N, Bergé M, Sulpice T, Lahtinen S, Ouwehand A, Langella P, Rautonen N, Sansonetti PJ, Burcelin R. Intestinal mucosal adherence and translocation of commensal bacteria at the early onset of type 2 diabetes: molecular mechanisms and probiotic treatment. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3(9):559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Denou E, Lolmède K, Garidou L, Pomie C, Chabo C, Lau TC, Fullerton MD, Nigro G, Zakaroff-Girard A, Luche E, Garret C, Serino M, Amar J, Courtney M, Cavallari JF, Henriksbo BD, Barra NG, Foley KP, McPhee JB, Duggan BM, O’Neill HM, Lee AJ, Sansonetti P, Ashkar AA, Khan WI, Surette MG, Bouloumié A, Steinberg GR, Burcelin R, Schertzer JD. Defective NOD2 peptidoglycan sensing promotes diet-induced inflammation, dysbiosis, and insulin resistance. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7(3):259–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yi-Jun Z, Ai L, Yu-Ling S, Yan L, Hui Y. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-1 ligand induces inflammation and attenuates glucose uptake in human adipocytes. Chin Med Sci J. 2012;27(3):147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Purohit JS, Hu P, Chen G, Whelan J, Moustaid-Moussa N, Zhao L. Activation of nucleotide oligomerization domain containing protein 1 induces lipolysis through NF-κB and the lipolytic PKA activation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;91(6):428–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chi W, Dao D, Lau TC, Henriksbo BD, Cavallari JF, Foley KP, Schertzer JD. Bacterial peptidoglycan stimulates adipocyte lipolysis via NOD1. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sharma A, Maurya CK, Arha D, Rai AK, Singh S, Varshney S, Schertzer JD, Tamrakar AK. Nod1-mediated lipolysis promotes diacylglycerol accumulation and successive inflammation via PKCδ-IRAK axis in adipocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865(1):136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhong H, SuYang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. The transcriptional activity of NF-kappaB is regulated by the IkappaB-associated PKAc subunit through a cyclic AMP-independent mechanism. Cell. 1997;89(3):413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhong H, Voll RE, Ghosh S. Phosphorylation of NF-kappa B p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol Cell. 1998;1(5):661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chan KL, Boroumand P, Milanski M, Pillon NJ, Bilan PJ, Klip A. Deconstructing metabolic inflammation using cellular systems. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2017;312(4):E339–E347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wentworth JM, Naselli G, Brown WA, Doyle L, Phipson B, Smyth GK, Wabitsch M, O’Brien PE, Harrison LC. Pro-inflammatory CD11c+CD206+ adipose tissue macrophages are associated with insulin resistance in human obesity. Diabetes. 2010;59(7):1648–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fink LN, Costford SR, Lee YS, Jensen TE, Bilan PJ, Oberbach A, Blüher M, Olefsky JM, Sams A, Klip A. Pro-inflammatory macrophages increase in skeletal muscle of high fat-fed mice and correlate with metabolic risk markers in humans. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(3):747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fink LN, Oberbach A, Costford SR, Chan KL, Sams A, Blüher M, Klip A. Expression of anti-inflammatory macrophage genes within skeletal muscle correlates with insulin sensitivity in human obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56(7):1623–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hadad N, Burgazliev O, Elgazar-Carmon V, Solomonov Y, Wueest S, Item F, Konrad D, Rudich A, Levy R. Induction of cytosolic phospholipase a2α is required for adipose neutrophil infiltration and hepatic insulin resistance early in the course of high-fat feeding. Diabetes. 2013;62(9):3053–3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Talukdar S, Oh DY, Bandyopadhyay G, Li D, Xu J, McNelis J, Lu M, Li P, Yan Q, Zhu Y, Ofrecio J, Lin M, Brenner MB, Olefsky JM. Neutrophils mediate insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet through secreted elastase. Nat Med. 2012;18(9):1407–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Morigny P, Houssier M, Mouisel E, Langin D. Adipocyte lipolysis and insulin resistance. Biochimie. 2016;125:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell. 2012;148(5):852–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Greene MW, Ruhoff MS, Roth RA, Kim JA, Quon MJ, Krause JA. PKCdelta-mediated IRS-1 Ser24 phosphorylation negatively regulates IRS-1 function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349(3):976–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Li Y, Soos TJ, Li X, Wu J, Degennaro M, Sun X, Littman DR, Birnbaum MJ, Polakiewicz RD. Protein kinase C theta inhibits insulin signaling by phosphorylating IRS1 at Ser(1101). J Biol Chem. 2004;279(44):45304–45307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moeschel K, Beck A, Weigert C, Lammers R, Kalbacher H, Voelter W, Schleicher ED, Häring HU, Lehmann R. Protein kinase C-zeta-induced phosphorylation of Ser318 in insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) attenuates the interaction with the insulin receptor and the tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(24):25157–25163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ravichandran LV, Esposito DL, Chen J, Quon MJ. Protein kinase C-zeta phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate-1 and impairs its ability to activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in response to insulin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(5):3543–3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bezy O, Tran TT, Pihlajamäki J, Suzuki R, Emanuelli B, Winnay J, Mori MA, Haas J, Biddinger SB, Leitges M, Goldfine AB, Patti ME, King GL, Kahn CR. PKCδ regulates hepatic insulin sensitivity and hepatosteatosis in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2504–2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Frangioudakis G, Burchfield JG, Narasimhan S, Cooney GJ, Leitges M, Biden TJ, Schmitz-Peiffer C. Diverse roles for protein kinase C delta and protein kinase C epsilon in the generation of high-fat-diet-induced glucose intolerance in mice: regulation of lipogenesis by protein kinase C delta. Diabetologia. 2009;52(12):2616–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kim JK, Fillmore JJ, Sunshine MJ, Albrecht B, Higashimori T, Kim DW, Liu ZX, Soos TJ, Cline GW, O’Brien WR, Littman DR, Shulman GI. PKC-theta knockout mice are protected from fat-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(6):823–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kumashiro N, Erion DM, Zhang D, Kahn M, Beddow SA, Chu X, Still CD, Gerhard GS, Han X, Dziura J, Petersen KF, Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Cellular mechanism of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(39):16381–16385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Szendroedi J, Yoshimura T, Phielix E, Koliaki C, Marcucci M, Zhang D, Jelenik T, Müller J, Herder C, Nowotny P, Shulman GI, Roden M. Role of diacylglycerol activation of PKCθ in lipid-induced muscle insulin resistance in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(26):9597–9602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Grant RW, Stephens JM. Fat in flames: influence of cytokines and pattern recognition receptors on adipocyte lipolysis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;309(3):E205–E213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kawakami M, Murase T, Ogawa H, Ishibashi S, Mori N, Takaku F, Shibata S. Human recombinant TNF suppresses lipoprotein lipase activity and stimulates lipolysis in 3T3-L1 cells. J Biochem. 1987;101(2):331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. van Hall G, Steensberg A, Sacchetti M, Fischer C, Keller C, Schjerling P, Hiscock N, Møller K, Saltin B, Febbraio MA, Pedersen BK. Interleukin-6 stimulates lipolysis and fat oxidation in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(7):3005–3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kosteli A, Sugaru E, Haemmerle G, Martin JF, Lei J, Zechner R, Ferrante AW Jr. Weight loss and lipolysis promote a dynamic immune response in murine adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(10):3466–3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, Waget A, Delmée E, Cousin B, Sulpice T, Chamontin B, Ferrières J, Tanti JF, Gibson GR, Casteilla L, Delzenne NM, Alessi MC, Burcelin R. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1761–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1470–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Scheithauer TP, Dallinga-Thie GM, de Vos WM, Nieuwdorp M, van Raalte DH. Causality of small and large intestinal microbiota in weight regulation and insulin resistance. Mol Metab. 2016;5(9):759–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zhao L, Kwon MJ, Huang S, Lee JY, Fukase K, Inohara N, Hwang DH. Differential modulation of Nods signaling pathways by fatty acids in human colonic epithelial HCT116 cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(16):11618–11628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zhou YJ, Tang YS, Song YL, Li A, Zhou H, Li Y. Saturated fatty acid induces insulin resistance partially through nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 signaling pathway in adipocytes. Chin Med Sci J. 2013;28(4):211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Duggan BM, Foley KP, Henriksbo BD, Cavallari JF, Tamrakar AK, Schertzer JD. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors of Ripk2 attenuate bacterial cell wall-mediated lipolysis, inflammation and dysglycemia. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Haile PA, Votta BJ, Marquis RW, Bury MJ, Mehlmann JF, Singhaus R Jr, Charnley AK, Lakdawala AS, Convery MA, Lipshutz DB, Desai BM, Swift B, Capriotti CA, Berger SB, Mahajan MK, Reilly MA, Rivera EJ, Sun HH, Nagilla R, Beal AM, Finger JN, Cook MN, King BW, Ouellette MT, Totoritis RD, Pierdomenico M, Negroni A, Stronati L, Cucchiara S, Ziółkowski B, Vossenkämper A, MacDonald TT, Gough PJ, Bertin J, Casillas LN. The identification and pharmacological characterization of 6-(tert-butylsulfonyl)-N-(5-fluoro-1H-indazol-3-yl)quinolin-4-amine (GSK583), a highly potent and selective inhibitor of RIP2 kinase. J Med Chem. 2016;59(10):4867–4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Haile PA, Casillas LN, Bury MJ, Mehlmann JF, Singhaus R Jr, Charnley AK, Hughes TV, DeMartino MP, Wang GZ, Romano JJ, Dong X, Plotnikov NV, Lakdawala AS, Convery MA, Votta BJ, Lipshutz DB, Desai BM, Swift B, Capriotti CA, Berger SB, Mahajan MK, Reilly MA, Rivera EJ, Sun HH, Nagilla R, LePage C, Ouellette MT, Totoritis RD, Donovan BT, Brown BS, Chaudhary KW, Gough PJ, Bertin J, Marquis RW. Identification of quinoline-based RIP2 kinase inhibitors with an improved therapeutic index to the hERG ion channel. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2018;9(10):1039–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Correa RG, Khan PM, Askari N, Zhai D, Gerlic M, Brown B, Magnuson G, Spreafico R, Albani S, Sergienko E, Diaz PW, Roth GP, Reed JC. Discovery and characterization of 2-aminobenzimidazole derivatives as selective NOD1 inhibitors. Chem Biol. 2011;18(7):825–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Khan PM, Correa RG, Divlianska DB, Peddibhotla S, Sessions EH, Magnuson G, Brown B, Suyama E, Yuan H, Mangravita-Novo A, Vicchiarelli M, Su Y, Vasile S, Smith LH, Diaz PW, Reed JC, Roth GP. Identification of inhibitors of NOD1-induced nuclear factor-κB activation. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2(10):780–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Stroo I, Butter LM, Claessen N, Teske GJ, Rubino SJ, Girardin SE, Florquin S, Leemans JC. Phenotyping of Nod1/2 double deficient mice and characterization of Nod1/2 in systemic inflammation and associated renal disease. Biol Open. 2012;1(12):1239–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]