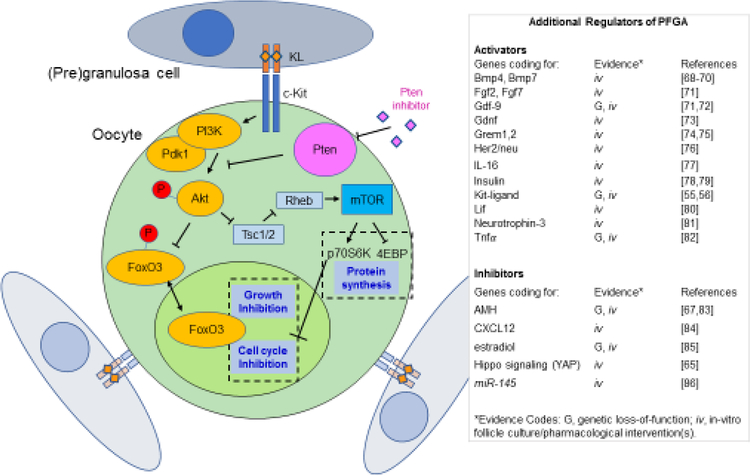

Figure 2. Molecular regulation of PFGA in Mice.

The cartoon on the left depicts primordial follicles consisting of a primordial oocyte and a few pregranulosa cells stay dormant due to the negative regulation of cell growth and the cell cycle by transcription factor FoxO3, and negative regulation of the mTOR signaling pathway, both controlled by the upstream action of Pten [69,93,105]. Accordingly, pharmacological inhibition of Pten using molecules such as bpV(HOpic) can result in enhanced PFGA. FoxO3 has been shown to inhibit the cell cycle via regulation of Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1b (Cdkn1b/p27). Oocytes with low mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) activity are likely to be held in a state of low protein synthesis due to a lack of phosphorylation of the mTOR target Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein (4-EBP), remaining out of an active cell cycle due to activity of P70S6-kinase (P70S6K), itself a positive regulator of cyclin D1, cyclin dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), and Retinoblastoma (Rb) proteins [106]. The table on the right presents an updated list of genes and factors shown to impact PFGA, with experimental evidence categorized by in vitro and/or in vivo genetic evidence. Cartoon adapted from [105].