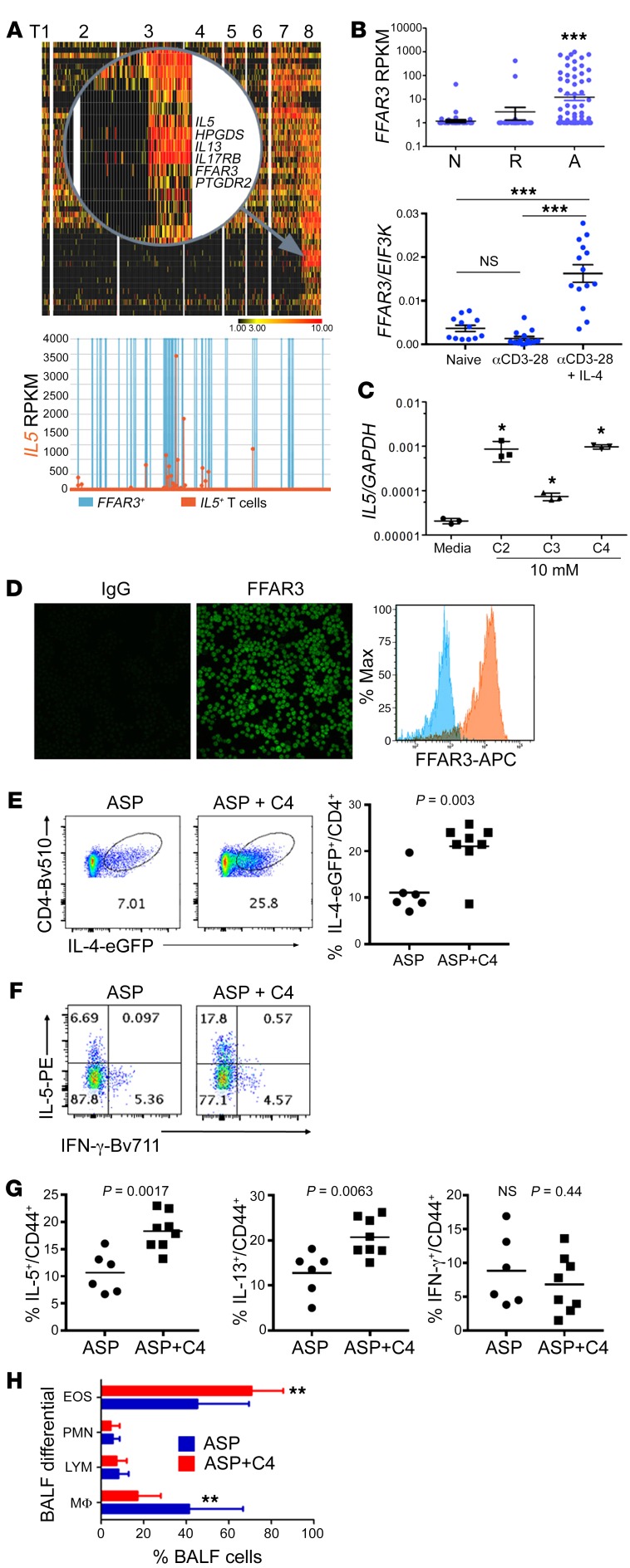

Figure 8. FFAR3 induction and Th2-enhancing effects of butyrate.

(A) A magnified view in the upper panel emphasizing the IL5-correlating genes specifically present in the T8 cluster, with FFAR3 tracking with IL5 expression shown in the lower panel (orange, IL5 producers; blue, FFAR3+ T cells). (B) Upper panel: the single-cell expression patterns of FFAR3 across 3 disease activity states (N, normal; R, remission; A, active EoE), with each data point representing 1 of the 1088 tissue T cells. Lower panel: with 3 days of Th2 differentiation (anti–CD3-CD28 [activated] with or without IL-4), human blood CD4+ T cells isolated from patients with EoE upregulated FFAR3 transcript induced by αCD3-CD28 (activation) plus IL-4 but not αCD3-CD28 (activation) alone. (C) IL5 transcript production by human Jurkat cells following short-chain fatty acid exposures (C2, C3, and C4 each at 10 mM for 24 hours). (D) Jurkat cells express FFAR3 on the cell surface by immunofluorescence and FACS. Original magnification, ×400. (E) In a murine asthma model, eGFP–IL-4 reporter mice were aspergillus allergen–challenged (ASP-challenged) intranasally with and without C4 (1 mg coadministration). IL-4–eGFP expression in CD4+ cells was analyzed by FACS. (F and G) Lung tissue CD4+ lymphocytes were assayed for Th1 and Th2 cytokine production by FACS. (H) The bronchoalveolar fluid (BALF) cells were quantified for major leukocyte populations. EOS, eosinophils; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophils; LYM, lymphocytes; MΦ, macrophages. All scatter plots are presented as mean ± SEM, and all experiments were repeated at least 3 times (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; 2-tailed t test).