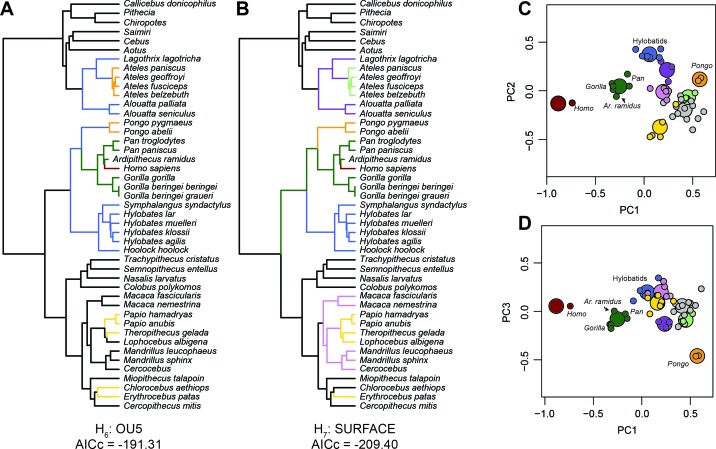

Figure 3. Evolutionary modeling.

Best fitting evolutionary models. (A) Best fitting a priori evolutionary hypothesis according to OUCH. (B) Arrangement of selective regimes fit by SURFACE. (C) The first two principal components with phenotypic optima estimated by SURFACE. (D) The first and third principal components with phenotypic optima estimated by SURFACE. Note the tight fit of species means (small dots) around their optima (large dots) as well as the placement of Ar. ramidus near the African ape phenotypic optimum. The colors in C and D correspond to the selective regimes painted onto the phylogeny in B.