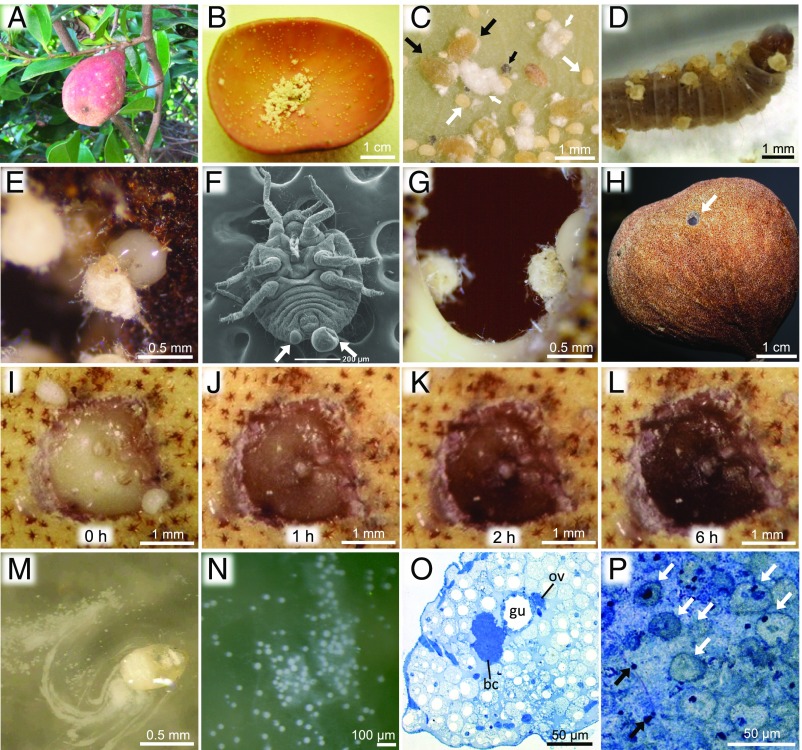

Fig. 1.

Self-sacrificing gall repair by soldier nymphs of N. monzeni. (A) A gall formed on the tree D. racemosum. (B) An inside view of a gall. (C) A magnified image of gall contents: white arrow, first-instar soldier nymph; black arrow, adult; small white arrow, powdery aggregate consisting of excreted wax; small black arrow, aphid cadaver. (D) Soldier nymphs attacking a moth larva by stinging with their stylet. (E) A gall-repairing soldier nymph discharging body fluid. (F) Scanning EM image of a soldier nymph (ventral view); arrows indicate droplets of body fluid discharged from cornicles. (G) Soldier nymphs plastering their own body fluid onto plant injury (Movie S1). (H) A gall with a naturally repaired hole (arrow). (I–L) An experimentally bored hole filled by body fluid of soldier nymphs at 0 h (I), 1 h (J), 2 h (K), and 6 h after plugging (L). (M) LGCs discharged from a soldier nymph (Movie S2). (N) An enlarged image of LGCs. (O) An abdominal cross-section of a soldier nymph whose body cavity is full of LGCs: bc, bacteriome; gu, midgut; ov, ovary. (P) A thin section of a solidified soldier’s body fluid 3 d after gall repair; white arrows indicate unruptured LGCs and black arrows indicate nuclei of ruptured LGCs.