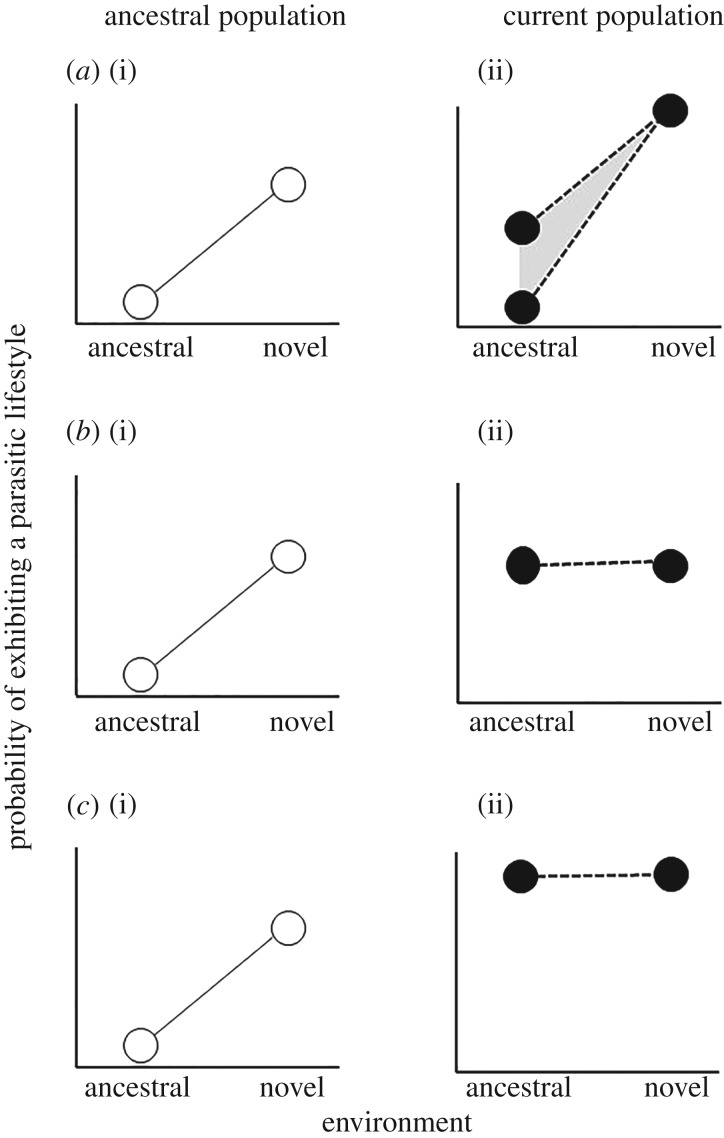

Figure 1.

Illustration of three scenarios of genetic accommodation in facultative parasites. (a(i), b(i) and c(i)) Ancestral, free-living populations that exhibit an increased probability of exhibiting a parasitic lifestyle when exposed to novel environmental conditions. (a(ii), b(ii) and c(ii)) Current populations following genetic accommodation. (a) The Baldwin effect. Expected phenotypes for the population if phenotypic plasticity exhibited in the ancestral population was adaptive, but was less than the optimal level of parasitism. Plasticity provided the opportunity for natural selection to act on heritable variants such that the mean phenotypic value further increased in the novel environment. Whether selection for higher trait expression in the novel environment is associated with concurrent changes in the mean trait expression in the ancestral environment will depend on the extent of genetic correlation between intercept and slope (illustrated by the grey region). Note that the Baldwin effect alone (shown in c(ii)) would not lead to complete loss of the free-living lifestyle. (b) Genetic assimilation. Plasticity exhibited by the ancestral population produced the optimal phenotype in the novel environment, in this case, 100% chance of adopting a parasitic lifestyle. Selection then acted to reduce phenotypic plasticity, such that the novel trait (parasitism) no longer requires the novel environmental cue to induce its expression. The current population is exclusively parasitic across all environments (i.e. obligate parasites). (c) Genetic assimilation and the Baldwin effect. The evolution of obligate parasitism occurred via selection on mean propensity to behave parasitically in the novel environment, coincident with selection for reduced plasticity.