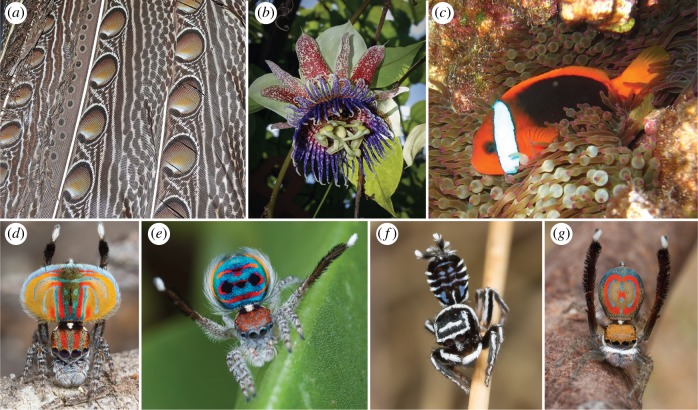

Figure 1.

Open questions about visual signals. The design of visual communication signals has puzzled biologists since Darwin, who agreed with his contemporaries that (a) feathers of the great argus pheasant Argusianus argus (credit: Bernard Dupont) were ‘more like a work of art than of nature’ [1, p. 258]. The design of a signal—the arrangement of its features—can be complex, as in (b) the flower of Passiflora maliformis (credit: Nick Hobgood), or simple, as in (c) the clownfish Amphiprion melanopus (credit: Richard Ling). Regardless, in most cases, there is no clear answer as to why the features of a signal are arranged as they are. Design diversification is just as enigmatic, as in (d–g) the Maratus genus of jumping spider (credits: Jurgen Otto). Why should the abdomen of one species feature red vertical bars surrounded by yellow patches transected by thin, curved blue lines (d), while its close congener sports dark eyespots and thick horizontal red bars on a background of turquoise blue surrounded by a yellow margin (e)? Extreme signal diversification is commonly attributed to the model of Lande [2], which hypothesizes that the trajectory of signal evolution changes with drift, or chance changes in female preferences; however, drift alone would ultimately produce random noise. It is generally accepted that receiver psychology influences the selection of signal design, and in some cases, selected designs are more effective in transmitting information than non-preferred designs [3]. Why this occurs is still unknown. For two decades, cognitive scientists have studied the efficacy and the efficiency (§3) of artistic paintings in stimulating the perceptual, cognitive and emotional systems of humans. We propose that their results can shed light on the evolution of nature's designs.