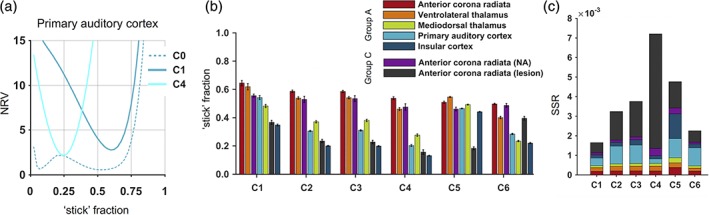

Figure 5.

Using different constraints yielded different rankings with respect to the “stick” fraction. (a) The constrained models (solid lines, here C1 and C4; Table 1) yielded precise estimates of the “stick” fraction, seen by the narrow ranges of (fixed) values that yielded a high goodness of fit (Equation (18)) compared to for the minimally constrained model (dashed line, C0). (b) the six constrained models yielded rather different “stick” fraction patterns, and produced significantly different rankings (p = 0.025). Thus, this set of “stick” fractions lacks ordinal accuracy across the domain represented by the healthy brain and white matter lesions, and using these models to index the neurite density may yield constraint‐dependent results. For example, while constraint set C1 would indicate a higher “neurite density” in the mediodorsal thalamus compared to in white matter lesions, set C6 would indicate the opposite. The error bars indicate standard errors. (c) The quality of fit (in terms of a low sum of squared residuals, SSR) was generally high in white matter and in the thalamus, but not always in the cortex or in white matter lesions. In the cortex, only set C4, which featured a CSF compartment, obtained a good fit. In white matter lesions, only sets allowing different compartment T2 values (C1 and C6) obtained a good fit. Note that quality of fit is not enough to rule out poor constraints. For example, using sets C1 and C6, comparing the mediodorsal thalamus with white matter lesions yielded similar fit qualities but different results, while using sets C3 and C4 yielded the opposite [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]