To the Editor:

The examination of urine to diagnose disease is an age-old practice, dating back thousands of years in primitive forms, and arguably represents the genesis of laboratory medicine.1 Microscopic evaluation of urine was introduced in the 19th century, and in the 20th century became a cornerstone of the nephrologist’s armamentarium for diagnosing kidney disease. Since the introduction of automated urine analyzers, manual examination of the urine sediment has rapidly fallen out of favor among clinicians.2, 3, 4 Despite its central role in the evaluation of patients with kidney disease, limited data are available in the literature on the test performance characteristics of the modern urinalysis (UA) as reported by laboratories using automated analyzers.5 In a cross-sectional analysis, we studied how well automated UAs distinguished proliferative glomerulonephritis (PGN) from other forms of kidney disease in a cohort of adult patients who had not yet been initiated on immunosuppressive therapy, and for whom clinicopathologic diagnoses were uniformly adjudicated by native kidney biopsies.

Results

A total of 512 patients were included in the analysis, 511 of whom had automated urine test strip results available and 421 of whom had urine red blood cell (RBC) counts available within 30 days before undergoing native kidney biopsy (Supplementary Figure S1). Of the 512 patients included in the analysis, 134 had PGN. The most common PGN diagnoses were IgA nephropathy (n = 74), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody−associated vasculitis (n = 19), and proliferative forms of lupus nephritis (n = 11). The most common non-PGN diagnoses were diabetic nephropathy (n = 63), membranous nephropathy (n = 38), and secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (n = 35) (Supplementary Table S1). The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 ± 15.9 years, 46.3% were female, and 68.6% were white. The median estimated glomerular filtration rate was 44.9 (interquartile range [IQR] 26.3–76.8) ml/min per 1.73 m2, and median proteinuria was 2.0 (IQR 0.6−5.0) g/g creatinine (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohort

| Characteristic | PGN (n = 134) | Other kidney disease (n = 378) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 50.5 ± 17.5 | 55.1 ± 15.2 | <0.01 |

| Female (%) | 46.3 | 46.3 | 0.99 |

| Race (%) | <0.01 | ||

| White | 66.7 | 69.3 | |

| Black | 11.6 | 21.4 | |

| Other | 21.7 | 9.3 | |

| Median serum creatinine (μmol/l) | 138 (97–203) | 144 (88–214) | 0.73 |

| Median eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 47.6 (29.3–69.2) | 42.5 (24.8–77.4) | 0.54 |

| Median proteinuria (g/g creatinine) | 1.8 (0.8–3.7) | 2.1 (0.5–5.5) | 0.69 |

| Median urine RBC count per HPF | 18 (6–60) | 2 (1–10) | <0.01 |

| Urine dipstick blood (%) | <0.01 | ||

| None or trace | 8.3 | 43.6 | |

| 1+ | 8.3 | 18.4 | |

| 2+ | 21.8 | 17.8 | |

| 3+ | 61.6 | 20.2 | |

| DM (%) | 10.5 | 28.3 | <0.01 |

| HTN (%) | 43.3 | 56.4 | <0.01 |

| ACEI/ARB (%) | 37.3 | 47.1 | 0.05 |

| Indications for biopsya (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Proteinuria | 67.9 | 52.9 | |

| Hematuria | 46.3 | 16.9 | |

| Abnormal GFR | 50.8 | 54.5 | |

| Most common primary clinicopathologic diagnoses | IgA nephropathy (n = 74) | Diabetic nephropathy (n = 63) | |

| ANCA-associated vasculitis (n = 19) | Membranous nephropathy (n = 38) | ||

| Proliferative lupus nephritis (n = 11) | Secondary FSGS (n = 35) | ||

| Immune complex GN (n = 11) | Advanced chronic changes (n = 29) | ||

| Cryoglobulinemic GN (n = 4) | Vascular sclerosis (n = 26) |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; GN, glomerulonephritis; HPF, high-power field; HTN, hypertension; PGN, proliferative glomerulonephritis.

Individual patients may have more than 1 indication for biopsy.

Patients with PGN had a median urine RBC count of 18 (IQR 6−60) per high-power field (HPF), whereas those with other forms of kidney disease had a median urine RBC count of 2 (IQR 1−10) per HPF (P < 0.01). Moreover, among the patients with PGN, we found a trend toward higher RBC counts in patients with crescentic disease compared to those without glomerular crescents (median [IQR] 23.5 (11.5−92.5) vs. 15 (4−60) RBCs/HPF, respectively, P = 0.06). Of the patients with PGN, 8.3% had less than 1+ blood on their test strip compared to 43.6% of those with other forms of kidney disease. The Spearman correlation coefficient between test strip blood measurements and the urine RBC count was 0.66.

Table 2 demonstrates the performance characteristics of automated urine test strip protein and blood at different thresholds for diagnosis of PGN versus other causes of kidney disease. Table 3 shows the same performance characteristics for quantitative proteinuria measurements and automated urine RBC counts. Figure 1 shows receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for diagnosis of PGN versus other causes of kidney disease using test strip blood or the automated urine RBC count as predictors. The areas under these ROC curves were 0.77 and 0.75, respectively. The difference in the ROC curves was not significant when compared among patients who had both tests performed (P = 0.15). Using the laboratory’s conventional threshold of >2 RBCs/HPF to define abnormal hematuria, the RBC count had 86% sensitivity, 51% specificity, 39% positive predictive value (PPV), and 91% negative predictive value (NPV) for PGN. Among patients with proteinuria <0.5 g/g creatinine, NPV increased to 96%. Analogously, a negative test strip for blood had 95% sensitivity, 29% specificity, 32% PPV, and 94% NPV. The NPV increased to 96% when restricted to patients with proteniuria <0.5 g/g creatinine.

Table 2.

Sensitivity (Sens), specificity (Spec), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), postive likelihood ratio (LR+), and negative likelihood ratio (LR−) at different thresholds of test strip protein and blood for diagnosis of proliferative glomerulonephritis

| Blood ≥0 | Blood ≥TR | Blood ≥1+ | Blood ≥2+ | Blood 3+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein ≥0 | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 94.7/29.0 | 91.7/43.6 | 83.5/62.0 | 61.7/79.8 | |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 32.1/94.0 | 36.5/93.7 | 43.7/91.4 | 51.9/85.5 | |

| LR+/LR− | 1.33/0.18 | 1.71/0.18 | 2.18/0.27 | 3.05/0.48 | |

| Protein ≥TR | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 94.7/14.6 | 90.9/37.0 | 88.6/50.0 | 81.1/65.4 | 59.9/82.2 |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 28.1/88.7 | 33.6/92.1 | 38.4/92.6 | 45.2/90.8 | 54.1/85.4 |

| LR+/LR− | 1.11/0.36 | 1.44/0.25 | 1.77/0.23 | 2.34/0.29 | 3.37/0.49 |

| Protein ≥1+ | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 85.7/24.4 | 81.8/43.1 | 81.1/54.8 | 74.2/68.9 | 55.3/84.3 |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 28.6/82.9 | 33.5/87.1 | 38.6/89.2 | 45.6/88.4 | 55.3/84.3 |

| LR+/LR− | 1.13/0.59 | 1.44/0.42 | 1.79/0.34 | 2.39/0.37 | 3.52/0.53 |

| Protein ≥2+ | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 73.7/36.1 | 70.5/49.5 | 69.7/59.6 | 63.6/71.8 | 47.7/85.9 |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 28.9/79.5 | 32.9/82.7 | 37.7/84.9 | 44.2/84.9 | 54.3/82.4 |

| LR+/LR− | 1.15/0.73 | 1.40/0.60 | 1.73/0.51 | 2.26/0.51 | 3.38/0.61 |

| Protein ≥3+ | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 39.1/61.3 | 36.4/66.2 | 36.4/72.6 | 33.3/80.3 | 25.0/91.2 |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 26.3/74.0 | 27.4/74.8 | 31.8/76.5 | 37.3/77.4 | 50.0/77.6 |

| LR+/LR− | 1.01/0.99 | 1.08/0.96 | 1.33/0.88 | 1.69/0.83 | 2.84/0.82 |

TR, trace.

Table 3.

Sensitivity (Sens), specificity (Spec), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), postive likelihood ratio (LR+), and negative likelihood ratio (LR−) for different thresholds of quantitative proteinuria and urine RBC counts for diagnosis of proliferative glomerulonephritis

| RBCs ≥0/HPF | RBCs >2/HPF | RBCs >5/HPF | RBCs >10/HPF | RBCs >15/HPF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein ≥0 g/g | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 85.7/51.4 | 76.2/62.3 | 61.0/75.7 | 50.5/81.2 | |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 38.8/90.9 | 42.1/87.9 | 47.4/84.4 | 49.1/82.0 | |

| LR+/LR− | 1.76/0.28 | 2.02/0.38 | 2.51/0.52 | 2.69/0.61 | |

| Protein ≥0.5 g/g | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 86.7/23.3 | 74.3/61.6 | 65.7/71.6 | 51.4/80.1 | 41.9/84.9 |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 28.9/82.9 | 41.1/87.0 | 45.4/85.3 | 48.2/82.1 | 50.0/80.3 |

| LR+/LR− | 1.13/0.57 | 1.93/0.42 | 2.31/0.48 | 2.58/0.61 | 2.77/0.68 |

| Protein ≥1.0 g/g | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 72.4/35.3 | 61.9/66.4 | 54.3/75.0 | 43.8/82.9 | 35.2/87.3 |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 28.7/78.0 | 39.9/82.9 | 43.9/82.0 | 47.9/80.4 | 50.0/79.0 |

| LR+/LR− | 1.12/0.78 | 1.84/0.57 | 2.17/0.61 | 2.56/0.68 | 2.77/0.74 |

| Protein ≥2.0 g/g | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 48.6/47.6 | 41.9/72.3 | 40.0/78.8 | 30.5/86.6 | 23.8/90.4 |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 25.0/72.0 | 35.2/77.6 | 40.4/78.5 | 45.1/77.6 | 47.2/76.4 |

| LR+/LR− | 0.93/1.08 | 1.51/0.80 | 1.89/0.76 | 2.28/0.80 | 2.48/0.84 |

| Protein ≥3.5 g/g | |||||

| Sens/Spec (%) | 28.6/62.0 | 26.7/78.4 | 25.7/83.9 | 20.0/90.1 | 16.2/93.8 |

| PPV/NPV (%) | 21.3/70.7 | 30.8/74.8 | 36.5/75.9 | 42.0/75.8 | 48.6/75.7 |

| LR+/LR− | 0.75/1.15 | 1.24/0.93 | 1.60/0.89 | 2.02/0.89 | 2.61/0.89 |

HPF, high-power field; RBC, red blood cell.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves demonstrating fair performance of the automated urine red blood cell (RBC) count and urine test strip blood for diagnosis of proliferative glomerulonephritis versus other forms of kidney disease. Depicted thresholds for the RBC count are given as the number per high-power field. AUC, area under the curve; TR, trace.

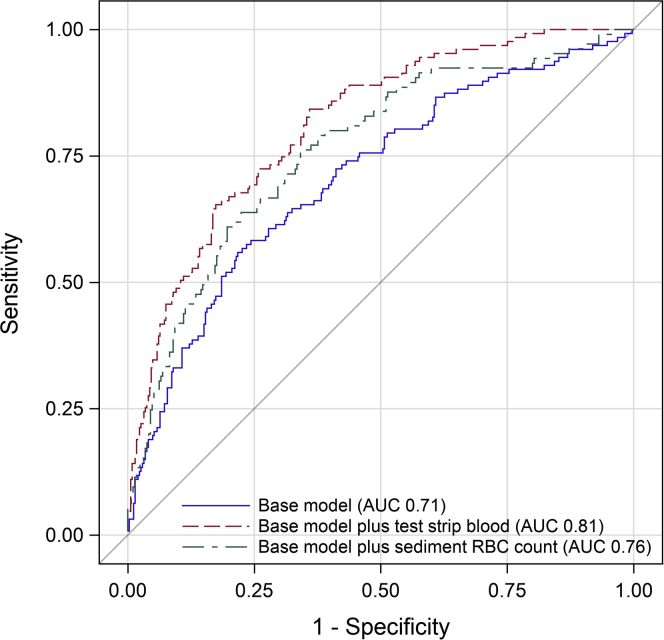

When test strip blood was added to a clinical prediction model of PGN which included age, sex, race (black vs. nonblack), proteinuria (<1 vs. ≥1 g/g creatinine), estimated glomerular filtration rate, acute kidney injury as the reason for biopsy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, and hepatitis C, the area under the ROC curve increased from 0.71 for the base model alone up to 0.81 (P < 0.01). Among patients for whom automated urine RBC counts were available, the addition of the RBC count instead of test strip blood to the same clinical prediction model increased the area under the ROC curve from 0.71 to 0.76 (P < 0.01) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A clinical prediction model of proliferative glomerulonephritis that included age, sex, race (black vs. nonblack), proteinuria (<1 vs. ≥1 g/g creatinine), estimated glomerular filtration rate, acute kidney injury as the reason for biopsy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, and hepatitis C significantly improved with the addition of test strip blood (P < 0.01) to the model, as well as with the addition of the sediment red blood cell (RBC) count among patients for whom this was available (P < 0.01). AUC, area under the curve.

Discussion

Our data show that the automated UA has fair ability to differentiate PGN from other kidney diseases. A negative urine RBC count or dipstick for blood had high negative predictive value, especially among patients with low levels of proteinuria, despite our cohort having a high proportion of patients with PGN. Both tests, however, had limited specificity and positive predictive value, and similar performance overall. It is possible that specificity and PPV would be higher in nonbiopsied chronic kidney disease cohorts, as most patients with diseases such as diabetic nephropathy or hypertensive nephrosclerosis do not undergo biopsy, and our cohort is thus likely to be enriched for atypical presentations of these diseases. Although this could affect the generalizability of our findings, the inclusion of only patients with biopsy-proven disease is a fundamental strength of our analysis. Without being able to compare our automated UA results to the results of the gold standard diagnostic method, ascertainment bias could lead to invalid estimates of the test performance characteristics.

Despite its limitations as a diagnostic test, the automated UA added significantly to a basic clinical prediction model of PGN. Among patients with PGN, we furthermore found a trend toward an association between higher levels of hematuria and more severe disease, as indicated by the presence of glomerular crescents. Although this finding was not statistically significant, our study may not have been adequately powered to detect a statistically significant difference. Taken together, our data demonstrate quantitatively how the automated UA may aid clinicians, albeit imperfectly, when determining the appropriateness of additional workup for kidney disease, such as serological studies and, ultimately, a kidney biopsy.

Interestingly, we found no difference between the performance characteristics of the urine RBC count and the semiquantitative test strip blood measurements for diagnosis of PGN. Because automated analyzers do not reliably detect less common but more specific features of PGN in the urine sediment, such as acanthocytes and RBC casts,6, 7 further studies are needed to compare the performance characteristics of the manual sediment examination when carried out by trained nephrologists to those of modern laboratory-based automated analyzers.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH R01DK093574 (SSW). RP was supported by an ASN Ben J. Lipps Research Fellowship Grant. We thank all members of the Waikar Lab for their work on the Boston Kidney Biopsy Cohort.

Footnotes

Supplementary Methods.

Figure S1. Overview of analysis cohort.

Table S1. Primary clinicopathologic diagnoses of patients in the analysis cohort.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.kireports.org.

Supplementary Material

Overview of analysis cohort.

Primary clinicopathologic diagnoses of patients in the analysis cohort.

References

- 1.Armstrong J.A. Urinalysis in Western culture: a brief history. Kidney Int. 2007;71:384–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker G.J., Garigali G., Fogazzi G.B. Advances in urine microscopy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:954–964. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogazzi G.B., Grignani S. Urine microscopic analysis. An art abandoned by nephrologists? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:2485–2487. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.10.2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perazella M.A. The urine sediment as a biomarker of kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:748–755. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.02.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai J.J., Yeun J.Y., Kumar V.A. Comparison and interpretation of urinalysis performed by a nephrologist versus a hospital-based clinical laboratory. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:820–829. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Köhler H., Wandel E., Brunck B. Acanthocyturia–a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int. 1991;40:115–120. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fogazzi G.B., Saglimbeni L., Banfi G. Urinary sediment features in proliferative and non-proliferative glomerular diseases. J Nephrol. 2005;18:703–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Overview of analysis cohort.

Primary clinicopathologic diagnoses of patients in the analysis cohort.