Abstract

Objective

We evaluated residual incontinence, depression, and quality of life among Malawian women who had undergone vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) repair 12 or more months ago.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Fistula Care Centre in Lilongwe, Malawi.

Population

Women who had undergone VVF repair in Lilongwe, Malawi at least 12 months prior to enrollment.

Methods

Self-report of urinary leakage was used to evaluate for residual urinary incontinence; depression was evaluated with the Patient health Questionnaire-9; quality of life was evaluated with the King’s Health Questionnaire.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence and predictors of residual incontinence, quality of life scores, and prevalence of depression and suicidal ideation.

Results

Fifty-six women (19.3%) reported residual urinary incontinence. In multivariable analyses, predictors of residual urinary incontinence included: pre-operative Goh type 3 (aRR=2.82; 95% CI:1·61, 5·27) or 4 (aRR=3.10; 95% CI:1.48, 6.50) VVF, more than one prior surgery (aRR=1.74; 95% CI:1.08, 2.78), positive post-operative cough stress test (aRR=2.42; 95% CI 1.24, 4.71) and the one-hour post-operative pad test (aRR=2.20; 95% CI:1.08, 4.48). Women with Goh types 3 and 4 VVF reported lower quality of life scores. Depressive symptoms were reported in 3.5% of women; all reported residual urinary incontinence.

Conclusions

While the majority of women reported improved outcomes in the years following surgical VVF repair, those with residual urinary incontinence had a poorer quality of life. Services are needed to identify and treat this at-risk group.

Keywords: obstetric fistula, residual incontinence, quality of life, depression, Africa, Malawi

Tweetable abstract

Nearly 1/5 of women reported residual urinary incontinence at follow-up 12 or months after vesicovaginal fistula repair.

Introduction:

Obstetric fistula (OF) affects an estimated 2 million women worldwide;1 in sub-Saharan Africa, the lifetime prevalence is as high as 3·0 per 1000 women of reproductive age.2 OF usually results from obstructed labor. Compression from the fetal head results in tissue necrosis in the pelvis and leads to communications between the vagina and the bladder and/or rectum. Vesicovaginal fistula (VVF), the most common type of OF, produces constant leaking of urine from the vagina. Its social consequences can be devastating and include stigma and social isolation, divorce, and depression.3

A growing number of facilities in sub-Saharan Africa now provide surgical repair of OF, including VVF. While outcomes have been promising, not all women regain continence following repair. The average fistula closure rate is 86%, and amongst these women, 70% are fully continent.4 Persistent incontinence after surgery for VVF has been termed the “continence gap.”5

One qualitative study found that women with residual incontinence reported poor quality of life, stigma, and mental health disorders,6 but little quantitative data exists on this topic. Acquisition of such data has proven challenging because of limited long-term follow-up of patients,7 high rates of program attrition8 and short duration (e.g., 3–6 months) of post-surgical monitoring.9 This is particularly true in the context of “fistula camps,” where surgeries are performed over intensive, short periods with little long-term care post-operative care.10 To address this gap, we conducted a follow-up study of VVF repair performed at least 12 months previously and investigated the prevalence of long-term residual incontinence and its associated risk factors. Our secondary objectives were to measure incontinence-associated quality of life scores and to screen for depression in women who previously underwent VVF repair.

Methods:

Study Setting

The Fistula Care Centre is located at Bwaila Hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi and was established in 2011 with support from the Freedom from Fistula Foundation. Malawi is a low-income country located in sub-Saharan Africa and is characterized by a heavy burden of disease evidenced by high levels of child and adult mortality rates and high prevalence of infectious diseases, high fertility rate, and high rates of maternal mortality and obstetric complications.11 The Centre treats patients from Malawi and neighboring countries (e.g., Mozambique, Zambia). Women are referred from other health facilities and, upon arrival, provide a detailed medical history and undergo a thorough physical examination. The medical team then provides options for long-term treatment, which may include surgical repair at the facility. Annually, 300–400 surgeries are performed at the Centre. From 2011–2015, most surgeries were performed or overseen by a single experienced fistula surgeon (JW). A review of our program database showed progressive declines in completion of clinical post-operative visits – from 80% at one month to 50% at three months to 20% at 12 months (J. Tang, personal communication, April 17, 2015). We obtained informed consent from patients to review this medical information – including demographic data, physical exam findings, surgical procedures, and post-operative findings – and to re-contact them to evaluate long-term clinical outcomes and program implementation.

Study design, recruitment and consent

To evaluate long-term outcomes, we enrolled a cohort of 300 women seeking follow-up care for obstetric fistula between January 1, 2012 and July 31, 2014, who had an obstetric VVF repair at the Centre at least 12 months ago.. Patients eligible for inclusion, were age 18 years or older, and residence within a four-hour drive from the Centre. Those with only a rectovaginal fistula were excluded. A trained staff member contacted eligible participants – identified from our clinical database – and scheduled a time to complete the study procedures in their home or another private setting. We implemented this approach because of the low proportion of women who return to the Centre after three months following surgery. All women provided additional informed consent prior to enrollment in this follow-up study.

Study procedures

At the follow-up visit, participants completed a survey that included demographic characteristics, medical history, HIV status, depression screening, and a quality of life assessment. The primary outcome of residual urinary incontinence was determined by self-report. We also conducted an objective evaluation of urinary incontinence to quantify the degree of incontinence (i.e., one-hour pad test; see below). All study data were double-entered into a REDCap database (Research Electronic Data Capture, NC).12 Ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Sciences Research Committee of Malawi (Lilongwe, Malawi) (Protocol #15/5/1428) and the University of North Carolina School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Chapel Hill, NC, USA) (Study # 15–0972). The research protocol was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02685878).

We assessed the participant’s quality of life by first asking, “How has your quality of life been since fistula repair/surgery? We then assessed domains of quality of life using the King’s Health Questionnaire, a validated tool specifically designed for women with urinary incontinence.13 Quality of life scores were calculated per the published protocol with a range of 0 “no bother” to 100 “marked bother” for each of the 8 domains and stratified by fistula Goh type measured prior to surgery.

We conducted depression screening using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),14 which has been internationally validated in several resource limited settings.15, 16 Each item is scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly everyday). Participants with a PHQ-9 score ≥10 were considered likely to have a depressive disorder. Any women with a PHQ-9 score of ≥10 – or who reported any suicidal ideation on the PHQ-9 – were referred for local mental health services. The PHQ-9 was translated into the local language (Chichewa) and the same version was utilized in recently-published studies examining postnatal depression in Malawi.17, 18 This version of the PHQ-9 was found to have concordance with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in our setting.

A one-hour pad test was concurrently performed during the follow-up survey interview to provide an objective measure of urinary incontinence. At the start of the interview, women were asked to use a pre-weighed extra-long feminine pad. After one hour, the pad was removed and weighed again, and the one-hour pad weight was calculated as the incremental difference. This method is commonly used for both pre-operative and post-operative assessment and has been shown to predict post-operative incontinence within 120 days of repair.19 The upper limit of continence for one-hour pad testing is recommended by the International Continence Society as 1·4 grams.20 We considered pad weights ≥1·5 grams as positive for incontinence.

Additional patient information

We received permission from patients to review their medical information at the Centre. This included the pre-operative fistula evaluation, including the Goh classification (Table S1),21 which grades the severity of VVFs by site, size, and scarring. Additionally, data was obtained from post-operative incontinence testing consisting of a dye test, a cough stress test, and the one-hour pad test., usually performed 2 weeks after surgery and prior to discharge from the Centre. Some women had more than one VVF repair and this testing was performed after each repair. Residual fistula was determined using the dye test, by noting if any dye instilled into the bladder leaks into the vagina. The cough stress test evaluates for stress urinary incontinence after dye installation (usually filled to 150 cc, but often limited by patient’s bladder capacity) by asking the patient to cough multiple times. The post-operative one-hour pad test was performed in the same manner as described above. When this was compared to the one-hour pad test performed at time of discharge, it was recorded as similar if the difference was half the standard deviation of pad weights at time of discharge (10.2g) or less, and a difference noted if greater than this amount.

Analytic Methods

The goal of this analysis was to measure the prevalence of residual incontinence through self-report and determine the demographic and medical characteristics associated with urinary incontinence at least 12 months after VVF repair. Pearson’s χ2 tests were used to calculate differences in the demographic and fistula characteristics between women who did and did not report incontinence at follow-up. We used log binomial models to evaluate pre- and post-operative predictors of long-term incontinence. Pre-operative variables tested included age at the time of fistula repair, Goh type, Goh fistula size, and vaginal scarring. Post-operative variables tested included need for more than one surgical repair, cough stress test and post-operative one-hour pad test after the most recent repair. Variables were included in multivariable models if they were conceptually related to or statistically associated (p-value <0.20) with residual incontinence in bivariable analysis. Generalized linear models were used for the multivariable analysis, with a log link and binomial distribution. Separate analyses were conducted for pre- and post-operative variables as pre-operative factors can affect post-operative factors. Bivariable analysis was performed to determine if results were sensitive to stratification by time between repair and follow-up survey. Quality of life scores from the King’s Health Questionnaire were calculated for each participant. These results were stratified by reported residual urinary incontinence and pre-operative Goh type. Frequency analysis was used to describe women with likely depressive disorder and suicidal symptoms. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 13·0 (StataCorp 2013, College Station, TX).

Role of the funding sources

The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of this report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results:

Study Population

From January 1, 2012 to July 31, 2015, 359 women who met eligibility criteria underwent surgical VVF repair (Figure S1). Between September 10, 2015 to March 17, 2016, women were recruited via home visits. Four women had died since their repair; another 10 had moved out of traceable areas or could not be contacted. All were excluded. We also excluded those living in the furthest two districts after reaching our target sample of 300 women.

Among our 300 recruited participants, we excluded ten from the final analysis. These included three women who had been incorrectly classified as having an obstetrical cause for their VVF; another seven only had a surgical repair of a rectovaginal fistula, without an accompanying VVF for a final sample size of 290. When compared to women with a VVF repair in the study time frame who were not included in the follow-up study due to residing outside of the study area (n=238), women in this follow-up study had more primary and less secondary education, were more likely to be a peasant farmer or housewife, less likely to have 3 or more children, have a Goh type 3 fistula (as compared to Goh type1/2 or Goh type 4) or have 3 or more follow-ups since repair (Table S2).

Participants had a median time of 35.5 months [IQR 27,43] from initial surgery to follow-up. A majority (84.8%) had undergone one prior repair, 10.3% had undergone 2 prior repairs, and 4.9% had undergone three or more repairs at the Centre. Thirty-four participants (11.7%) had not completed any clinical follow-up at the Centre.

Prevalence of residual urinary incontinence following VVF repair

Of the 290 participants, 56 (19.3%) self-reported residual urinary incontinence at the time of the follow-up. Women who reported urinary incontinence were older, had less education, had fewer living children, were more likely to have a VVF with Goh type 3 or 4, and had more repairs done at the Fistula Care Centre (all p<0.05, Table 1) compared to those who reported no incontinence.

Table 1:

Characteristics of women completing the follow-up study after VVF repair, by self-report of any urinary incontinence (n=290)

| All women (n=290) n (%) |

Reported urinary incontinence (n=56) n (%) |

No reported urinary incontinence (n=234) n (%) |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) n (%) | 0.003 | |||

| <20 | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.7) | |

| 20-49 | 228 (78.6) | 36 (64.3) | 192 (82.1) | |

| ≥50 | 58 (20.0) | 20 (35.7) | 38 (16.2) | |

| Relationship status n (%) | 0.602 | |||

| Married | 200 (69.0) | 37 (66.1) | 163 (69.7) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| None | 105 (36.2) | 35 (62.5) | 70 (29.9) | |

| Some primary | 173 (59.7) | 21 (37.5) | 152 (65.0) | |

| Some secondary | 12 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (5.1) | |

| Living children | 0.035 | |||

| 0 | 97 (33.5) | 26 (46.4) | 71 (30.3) | |

| 1-2 | 114 (39.3) | 21 (37.5) | 93 (39.7) | |

| HIV status | 0.122 | |||

| Positive | 22 (7.6) | 7 (12.5) | 15 (6.4) | |

| Goh typea | <0.001 | |||

| Type 1/2 | 149 (51.4) | 14 (25.0) | 135 (57.7) | |

| Type 3 | 92 (31.7) | 27 (48.2) | 65 (27.8) | |

| Type 4 | 33 (11.4) | 11 (19.6) | 22 (9.4) | |

| Missing/not assessed | 16 (5·5) | 4 (7.1) | 12 (5.1) | |

| Time from first repair at FCCa to follow-up study enrollment | 0.216 | |||

| 12-36 months | 151 (52.1) | 25 (44.6) | 126 (53.9) | |

| 37-50 months | 139 (47·9) | 31 (55·4) | 108 (46.1) | |

| Number of post-operative visits completed | 0.277 | |||

| 0 | 34 (11.7) | 10 (17.9) | 24 (10.3) | |

| 1 | 69 (23.8) | 14 (25.0) | 55 (23.5) | |

| 2 | 80 (27.6) | 11 (19.6) | 69 (29.5) | |

| ≥3 | 107 (36.9) | 21 (37.5) | 86 (36.8) | |

| Number of repairs at FCCa | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 246 (84.8) | 38 (67.9) | 208 (88.9) | |

| 2 | 30 (10.3) | 14 (25.0) | 16 (6.8) | |

| ≥3 | 14 (4.9) | 4 (7.1) | 7 (4.3) | |

| Residual fistula after last repair | 0.440 | |||

| No | 274 (94.5) | 51 (91.1) | 223 (95.3) |

FCC = Fistula Care Centre

Among women with a closed fistula at their last visit at the Centre, 14.9% self-reported urinary leakage during follow-up. Twenty-one (7.2%) women had a residual fistula at their last visit at the Centre. Of these 21 women, 16 (76.2%) women reported continued urinary incontinence at follow-up, and 5 (23.8%) reported no incontinence.

Predictors of residual incontinence

In bivariable analyses, pre-operative variables associated with reported residual incontinence included being ages 34–49 years or ages ≥50 years, Goh types 3 and 4, fistula >3 cm, and moderate/severe vaginal scarring (Table 2). In multivariable analysis, only Goh types 3 (aRR=2.82; 95% CI:1.61, 5.27) and 4 (aRR=3.10; 95% CI:1.48, 6.50) remained associated with incontinence.

Table 2:

Bivariable and multivariable predictors of reported urinary incontinence in the years following fistula repair using risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) Excluding missing

| Bivariable analysis RR (95% CI) |

Multivariable analysis RR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative factors | ||

| Age at time of repair (n=290) | ||

| 17-24 years | 1 | 1 |

| 25-34 years | 2.45 (0.75, 7.97) | - |

| 34-49 years | 3.75 (1.17, 12.02) | - |

| ≥50 years | 5.44 (1.70, 17.38) | - |

| Goh type (n=274) | ||

| 1/2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 3.12 (1.73, 5.64) | 2.82 (1.61, 5.27) |

| 4 | 3.55 (1.77, 7.10) | 3.10 (1.48, 6.50) |

| Goh size (n=271) | ||

| <1·5 cm | 1 | 1 |

| 1·5-3 cm | 1.50 (0.74, 3.04) | 0.72 (0.36, 1.44) |

| >3 cm | 2.22 (1.13, 4.37) | 0.95 (0.48, 1.87) |

| Vaginal scarring (n=271) | ||

| None/mild | 1 | 1 |

| Moderate/severe | 8.66 (1.23, 60.90) | 6.26 (0.87, 45.30) |

| Post-operative factors | ||

| Need for >1 repair (n=290) | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.65 (1.67, 4.20) | 1.74 (1.08, 2.78) |

| Post-operative cough stress test* (n=261) | ||

| Negative | 1 | 1 |

| Positive | 4.47 (2.55, 7.83) | 2.42 (1.24, 4.71) |

| Post-operative pad test * (n=266) | ||

| Negative | 1 | 1 |

| Positive | 4.27 (2.34, 7.77) | 2.20 (1.08, 4.48) |

After last surgery at the Fistula Care Centre

Post-operative characteristics associated with residual incontinence included >1 repair at the Centre, a positive cough stress test, and a positive pad test after the most recent VVF repair (in patients who had more than one VVF repair). In multivariable analysis, >1 repair (aRR=1.74; 95% CI:1.08, 2.78), a positive cough stress test (aRR=2.42; 95% CI:1.24, 4.71), and a positive pad test (aRR=2.2; 95% CI:1.08, 4.48) remained significantly associated with incontinence. When bivariable results were stratified by time from surgery to follow-up (12–36 months versus 37–50 months), results did not differ meaningfully from the primary analysis (Table S3).

Fifty women (17.2%) had a positive one-hour pad test at this long-term follow-up visit; of these, 49 (98.0%) reported residual incontinence. Among women with a positive pad test, the median weight was 12.7 g (range 1·9 – 65·9 g). 56 women reported incontinence and 39 (69.6%) had a positive post-operative one-hour pad test after their last repair, and 49 (87.5%) had a positive pad test at follow-up (Table S4). Among women reporting incontinence who had both a post-operative pad test and a long-term follow-up pad test, 25.0% had higher pad weights, 25.0% had lower pad weights, and 41.1% had similar pad weights at follow-up. In contrast, women without incontinence were more likely to have a lower or similar pad weight at follow-up than at the time of last repair (p<0.001).

Quality of Life

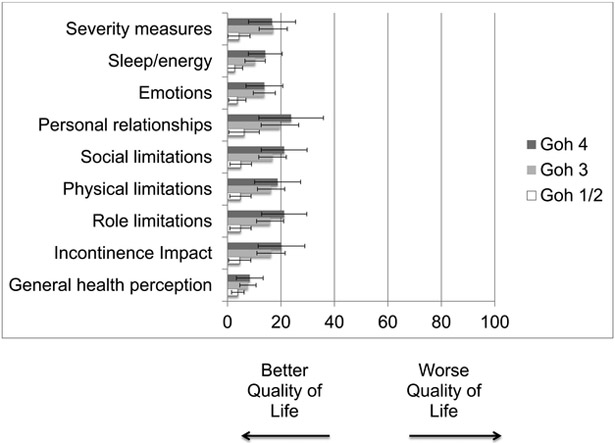

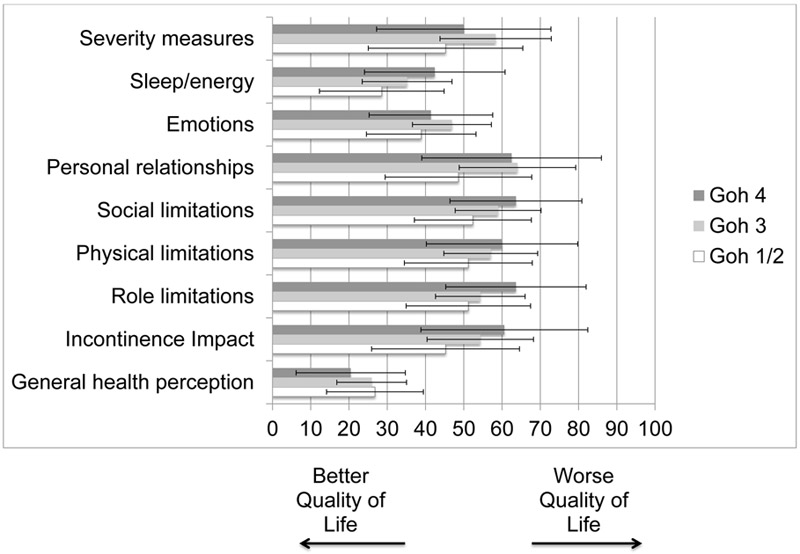

All women without residual urinary incontinence reported an improved quality of life. In contrast, only 30 of the 56 women (53.6%) with residual incontinence reported improved quality of life since repair. When stratifying quality of life scores in the King’s Health Questionnaire by fistula type prior to repair, women with pre-operative Goh type 4 had worse scores than those with Goh types 3 and were lower in nearly all domains of the King’s Health Questionnaire (Figure 1A), with the exception of general health perception. Women with reported incontinence had lower quality of life scores than those who did not, and pre-operative Goh type 4 fistula was associated with lower quality of life for the sleep/energy, social limitations, physical limitations, role limitations, and incontinence impact domains (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

A: Mean and 95% CI Quality of life scores at time of interview among all study participants (n=274*) according to fistula type prior to surgical repair *Excludes those with missing Goh type, n=16.

B: Mean and 95% CI Quality of life scores at time of interview among women reporting residual urinary incontinence (n=52*), according to fistula type prior to surgical repair *Excludes those with missing Goh type, n=4.

Depressive disorder and suicidal symptoms

Of the 290 participants, ten (3.5%) met PHQ-9 criteria for a likely depressive disorder (score ≥10). All ten women reported continued urinary incontinence; 8 reported worsened quality of life since their repair (Table 3). Nearly all women with a likely depressive disorder were married, 7 had no living children, and 5 had a previous hysterectomy. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 2.7%. There were four women with suicidal ideation but a PHQ-9 score <10 (1.4% of the total study population). All four of these women reported residual incontinence. Two had lower quality of life since repair, and 3 had no living children.

Table 3:

Characteristics of women with depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation at follow-up (n=10; 3·4%)

| Age | Self-reported incontinence |

Pad weight (grams) |

Overall QOL since repair |

Does incontinence affect QOL? |

Married | Number of living children |

Hysterectomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of women with depressive symptoms at follow-up (n=10; 3·4%) | |||||||

| 44 | Yes | 6.9 | Slightly improved | A lot/greatly | Yes | 0 | No |

| 45 | Yes | 45.1 | No different | A lot/greatly | Yes | 0 | Yes |

| 34 | Yes | 25.9 | A little worse | Moderately | Yes | 0 | Yes |

| 72 | Yes | 16.0 | A little worse | A lot/greatly | No | 1-2 | No |

| 26 | Yes | 25.1 | A little worse | A lot/greatly | Yes | 1-2 | Yes |

| 49 | Yes | 42.0 | Worse | A lot/greatly | Yes | 0 | Yes |

| 35 | Yes | 42.1 | Worse | Moderately | Yes | 0 | No |

| 48 | Yes | 36.0 | Worse | A lot/greatly | Yes | 0 | Yes |

| 50 | Yes | 8.5 | Much worse | A lot/greatly | Yes | 1-2 | No |

| 35 | Yes | 13.0 | Much worse | A lot/greatly | Yes | 0 | No |

| Characteristics of women with suicidal ideation at follow-up (n=4; 1·4%) | |||||||

| 30 | Yes | 1.4 | Slightly improved | Moderately | Yes | 0 | No |

| 30 | Yes | 12.0 | No different | A lot/greatly | Yes | ≥3 | No |

| 25 | Yes | 0.2 | A little worse | Not at all | No | 0 | No |

| 60 | Yes | 54.9 | Much worse | A lot/greatly | No | 0 | No |

QOL=quality of life

Discussion

Main Findings

In this cohort of 290 women with prior obstetric VVF repair, the majority reported improved health outcomes in the years following surgery. However, nearly one-fifth reported residual urinary incontinence. Fistula location prior to repair, >1 repair, cough stress test, and one-hour pad test prior to hospital discharge were predictive of self-reported incontinence 12 or more months after fistula repair. Women with incontinence scored lower on standardized quality of life scales and were the only ones who met criteria for major depression.

Strengths

To our knowledge, this study represents the largest cohort of obstetric VVF patients with long-term (i.e., over 12 months) follow-up after their index surgical repair. Other studies have had smaller numbers (range: 44–120 participants)22, 23 or more limited follow-up (3–6 months).9, 24 By relying on tracing and home-based follow-up, we were able to gather self-reported and objective measures of residual urinary incontinence.

Average prevalence of residual incontinence after VVF repair is reported by one literature review to be 30%,4. However, our findings are nearly identical to the 20% residual incontinence prevalence reported in a multi-country prospective study evaluating women 3 months after repair.24 Other studies have shown improvements in urinary incontinence from discharge to 6–12 months after surgery.9, 25 It is possible that women continue to regain further continence after this time period, even among women with small residual fistulas. However, such improvement is likely to eventually plateau. Additionally, as women age, their incontinence may worsen due to factors such as menopause.

Limitations

The heterogeneity of time to follow-up after repair (12–50 months) may have influenced the results in this study. Similar to other studies, pre-operative markers of fistula severity are associated with residual incontinence.24 In our study population, most repairs were performed or supervised by the same surgeon (JW) and a specialist surgical team trained for fistula repair. Hence, our findings may not be generalizable to other settings with less experienced staff or different surgical capabilities, different mixes of fistula types, or less comprehensive post-operative care.

Our primary outcome was residual urinary incontinence by self-report. Because the survey took place in the home and was administered by a non-medical staff member, none of the women underwent physical examination; in addition, urodynamic evaluation in Malawi is largely unavailable. Because of this, we are unable to comment on the etiology of urinary leakage: from persistent fistula versus stress, urge or overflow incontinence. Self-report of urinary incontinence has been shown in European populations to correlate with urodynamic findings.26 We were encouraged to find general concordance between self-reported urinary incontinence and the one-hour pad test, a standardized, objective measure.

In other settings, quality of life has been shown to be lower in women with residual incontinence from a persistent VVF.22 One study found no difference in the quality of life of women with persistent fistula before and after repair, but did find a difference between those with successful and unsuccessful fistula closure, regardless of urinary incontinence symptoms.25 Qualitative studies further characterize the ongoing distress and social limitations in women with residual incontinence.6 Lower quality of life scores after fistula repair are found in unmarried women with no living children.27 Time since repair has been described as a key factor in the recovery process. In one study, a majority of women required at least one year post-discharge to reach quality of life scores that matched scores of their perceived quality of life prior to fistula.28

Women with depression and suicidal ideation often had no living children and in some cases had a hysterectomy, removing the possibility of bearing future children. The ability to have and bear children is important to many women with fistula6, 29 although one study in Kenya found that childlessness and infertility were not associated with depression.30 We were surprised to find the low prevalence of depressive symptoms in our study cohort after fistula repair. In other contexts of fistula patients, pre-operative rates of depression have ranged from 59–97%.30, 31 Another study also found that women with residual incontinence have higher rates of depression (100%) after repair compared to those who are not leaking (29%).32 However in that study, the follow-up time after repair was only 2 weeks. Our findings may reflect the low rate of depressive disorders observed among Malawian women in the general population (3–15%).17, 33–35 Further research is needed in this field, including further validation of survey instruments among women with VVF.

Interpretation

Given the physical and psychological effects of residual incontinence on women after fistula repair, approaches are needed to identify and alleviate this incontinence. A study focused on reintegration revealed the need to address residual incontinence among women with repaired fistula as this adversely affects quality of life.28 Continence may be achieved in these women with further surgery or non-invasive techniques such as pelvic floor training or urethral plugs. Risk-stratification both pre- and post-operatively could help make individualized plans to address their medical and psychosocial needs.

Conclusions

Based on our findings, we make several recommendations about fistula services in places like Malawi. First, community-based approaches are needed to identify and evaluate women with residual urinary incontinence following VVF repair. Second, we recommend improving access to surgical and non-surgical therapies to improve long-term continence. Third, initiatives are needed that focus on the psychosocial impact of fistula repair, particularly for those with residual urinary incontinence. This may include mental health services, support groups, and community mentorship in culturally appropriate formats. Fourth, more data and tools are needed to better predict effectiveness of repair. Surgery carries significant morbidity in many resource limited settings. Understanding predictors may help refine surgical candidates and may also identify those in need of more conservative medical management and closer follow-up after surgery. Finally, fistula prevention is key through focusing resources on safe motherhood. These resources include family planning, patient and community education, maternity waiting homes, and improved access to safe and timely cesarean delivery. In working towards the goal of closing the “continence gap”, these important steps can be taken to improve each woman’s quality of life and mental health and ultimately, to restore her dignity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and staff at the Freedom from Fistula Care Centre in Lilongwe, Malawi, UNC Project-Malawi, the Lilongwe District Health Management Team, the staff and leadership of the UJMT Fogarty Global Health Fellows Program, and the following research assistants for their contributions to the study and assistance with recruitment and data collection, entry, and cleaning: William Nundwe, Charity Chisale, Rachel Hau, Sandra Ngwira, Sella Chisanga, Julia Ryan, Laura Drew, Allison Sih, Melike Harfouche, and Magdalena Zgambo.

Funding: This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R25 TW009340, T32 HD075731, K24 AI120796), the Freedom from Fistula Foundation, and the UNC Department of OB-GYN. Database assistance was supported by the North Carolina Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the Division of Research Resources grant [1UL1TR001111].

Footnotes

Disclosure of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Completed disclosure of interest forms are available to view online as supporting information.

Details of ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Sciences Research Committee of Malawi (Lilongwe, Malawi) (Protocol #15/5/1428) on 1 July 2015 and the University of North Carolina School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Chapel Hill, NC, USA) (Study # 15–0972) on 3 August 2016. The research protocol was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02685878).

References

- 1.Wall LL. Obstetric vesicovaginal fistula as an international public-health problem. Lancet. 2006. September 30;368(9542):1201–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maheu-Giroux M, Filippi V, Samadoulougou S, Castro MC, Maulet N, Meda N, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of vaginal fistula in 19 sub-Saharan Africa countries: a meta-analysis of national household survey data. The Lancet Global health. 2015. May;3(5):e271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed S, Holtz SA. Social and economic consequences of obstetric fistula: life changed forever? International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2007. November;99 Suppl 1:S10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrowsmith SD, Barone MA, Ruminjo J. Outcomes in obstetric fistula care: a literature review. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2013. October;25(5):399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wall LL, Arrowsmith SD. The “continence gap”: a critical concept in obstetric fistula repair. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007. August;18(8):843–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drew LB, Wilkinson JP, Nundwe W, Moyo M, Mataya R, Mwale M, et al. Long-term outcomes for women after obstetric fistula repair in Lilongwe, Malawi: a qualitative study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2016;16(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sjoveian S, Vangen S, Mukwege D, Onsrud M. Surgical outcome of obstetric fistula: a retrospective analysis of 595 patients. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2011. July;90(7):753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFadden E, Taleski SJ, Bocking A, Spitzer RF, Mabeya H. Retrospective review of predisposing factors and surgical outcomes in obstetric fistula patients at a single teaching hospital in Western Kenya. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011. January;33(1):30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browning A, Menber B. Women with obstetric fistula in Ethiopia: a 6-month follow up after surgical treatment. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2008. November;115(12):1564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cam C, Karateke A, Ozdemir A, Gunes C, Celik C, Guney B, et al. Fistula campaigns--are they of any benefit? Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2010. September;49(3):291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Organization WH. Malawi: Country Cooperation Strategy. 2017. [cited; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136935/ccsbrief_mwi_en.pdf;jsessionid=A2A7F94A5AE51E3407AB4CFF3A33F483?sequence=1

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009. April;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelleher CJ, Cardozo LD, Khullar V, Salvatore S. A new questionnaire to assess the quality of life of urinary incontinent women. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 1997. December;104(12):1374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine. 2001. September;16(9):606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cholera R, Gaynes BN, Pence BW, Bassett J, Qangule N, Macphail C, et al. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in a high-HIV burden primary healthcare clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of affective disorders. 2014;167:160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Atashili J, O’Donnell JK, Tayong G, Kats D, et al. Validity of an interviewer-administered patient health questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in HIV-infected patients in Cameroon. Journal of affective disorders. 2012. December 20;143(1–3):208–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington BJ, Hosseinipour MC, Maliwichi M, Phulusa J, Jumbe A, Wallie S, et al. Prevalence and incidence of probable perinatal depression among women enrolled in Option B+ antenatal HIV care in Malawi. Journal of affective disorders. 2018. June 23;239:115–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLean SA, Lancaster KE, Lungu T, Mmodzi P, Hosseinipour MC, Pence BW, et al. Prevalence and correlates of probable depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among female sex workers in Lilongwe, Malawi. International journal of mental health and addiction. 2018. February;16(1):150–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopp DM, Bengtson AM, Tang JH, Chipungu E, Moyo M, Wilkinson J. Use of a postoperative pad test to identify continence status in women after obstetric vesicovaginal fistula repair: a prospective cohort study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2017. May;124(6):966–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krhut J, Zachoval R, Smith PP, Rosier PF, Valansky L, Martan A, et al. Pad weight testing in the evaluation of urinary incontinence. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2014. June;33(5):507–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh JT. A new classification for female genital tract fistula. The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 2004. December;44(6):502–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen HS, Lindberg L, Nygaard U, Aytenfisu H, Johnston OL, Sorensen B, et al. A community-based long-term follow up of women undergoing obstetric fistula repair in rural Ethiopia. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2009. August;116(9):1258–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maulet N, Keita M, Macq J. Medico-social pathways of obstetric fistula patients in Mali and Niger: an 18-month cohort follow-up. Trop Med Int Health. 2013. May;18(5):524–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barone MA, Frajzyngier V, Ruminjo J, Asiimwe F, Barry TH, Bello A, et al. Determinants of postoperative outcomes of female genital fistula repair surgery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012. September;120(3):524–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castille YJ, Avocetien C, Zaongo D, Colas JM, Peabody JO, Rochat CH. One-year follow-up of women who participated in a physiotherapy and health education program before and after obstetric fistula surgery. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2015. March;128(3):264–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daan NM, Schweitzer KJ, van der Vaart CH. Associations between subjective overactive bladder symptoms and objective parameters on bladder diary and filling cystometry. Int Urogynecol J. 2012. November;23(11):1619–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imoto A, Matsuyama A, Ambauen-Berger B, Honda S. Health-related quality of life among women in rural Bangladesh after surgical repair of obstetric fistula. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2015. July;130(1):79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pope R, Bangser M, Requejo JH. Restoring dignity: social reintegration after obstetric fistula repair in Ukerewe, Tanzania. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(8):859–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mselle LT, Evjen-Olsen B, Moland KM, Mvungi A, Kohi TW. “Hoping for a normal life again”: reintegration after fistula repair in rural Tanzania. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012. October;34(10):927–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weston K, Mutiso S, Mwangi JW, Qureshi Z, Beard J, Venkat P. Depression among women with obstetric fistula in Kenya. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2011. October;115(1):31–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeleke BM, Ayele TA, Woldetsadik MA, Bisetegn TA, Adane AA. Depression among women with obstetric fistula, and pelvic organ prolapse in northwest Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Browning A, Fentahun W, Goh JT. The impact of surgical treatment on the mental health of women with obstetric fistula. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2007. November;114(11):1439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dow A, Dube Q, Pence BW, Van Rie A. Postpartum depression and HIV infection among women in Malawi. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2014. March 1;65(3):359–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart RC, Umar E, Tomenson B, Creed F. A cross-sectional study of antenatal depression and associated factors in Malawi. Archives of women’s mental health. 2014. April;17(2):145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCauley M, Madaj B, White SA, Dickinson F, Bar-Zev S, Aminu M, et al. Burden of physical, psychological and social ill-health during and after pregnancy among women in India, Pakistan, Kenya and Malawi. BMJ global health. 2018;3(3):e000625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.