Abstract

α-Galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) is a typical antigen for invariant natural killer T cells that are a subset of T cells and play critical roles in regulating immune responses. To selectively induce the secretion of certain cytokines via introducing hydrogen-bonding interaction with polar amino acid residues in the binding pocket of CD1d, a series of α-GalCer analogues with diether moiety in the acyl chain were designed and synthesized. The subsequent in vitro biological evaluation of these analogues revealed the structure–activity relationship for the selective IL-17 secretion. Analogues 5 and 6 induced the significantly increased IL-17 secretion over other cytokines, suggesting protective effects against pathogens. In contrast, analogue 7 showed the highly reduced IL-17 secretion, which may indicate potential anti-inflammatory effects.

Keywords: α-Galactosylceramide, CD1d, hydrogen bonding, rational design, Th17 selectivity

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are a subset of T cells and have critical functions in regulating innate immune responses.1−3 This immune regulatory function of iNKT cells comes from rapid secretion of various cytokines, which is distinct from other types of T cells.4,5 To elicit their immune responses, α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer)—a typical glycolipid antigen of iNKT cells—binds a CD1d protein on antigen-presenting cells (APC) to form α-GalCer/CD1d binary complex.6,7 T-cell receptor (TCR) on iNKT cells recognizes this binary complex, which stimulates iNKT cells.6,7 Once activated, iNKT cells secret various cytokines including T helper 1 (Th1), T helper 2 (Th2), and T helper 17 (Th17) cytokines.8−10 Th1 cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are pro-inflammatory cytokines having antitumor effects.8 Th2 cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) are anti-inflammatory cytokines, which suppress autoimmune diseases.8 Th17 cytokines represented by interleukin-17 (IL-17) are pro-inflammatory cytokines distinct from Th1 and Th2 cytokines.9,10 This immune response activated by iNKT cells can protect the body against pathogens, but its overproduction induces inflammation and autoimmune disorders.9,10 These released cytokines activate or suppress other immune cells and orchestrate immune responses.

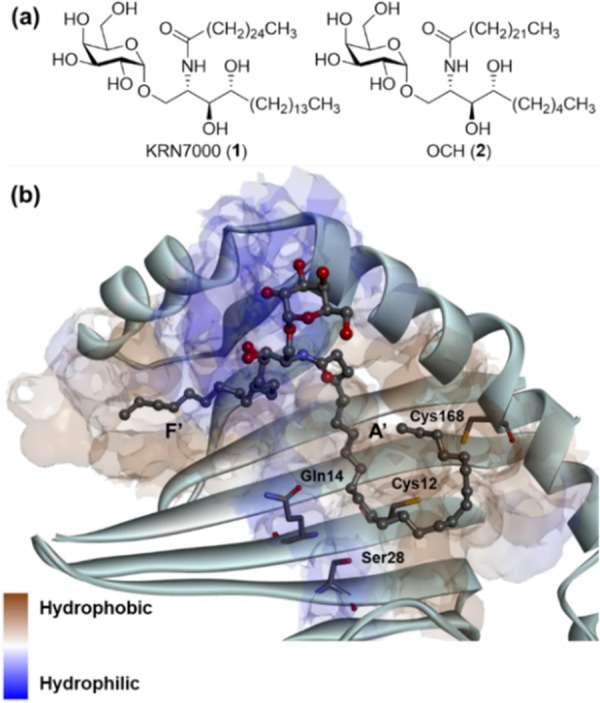

KRN7000 (1) is the representative synthetic α-GalCer (Figure 1a).11−15 Its role and therapeutic effects have been studied in various disease models, and its potent antitumor effects were verified in mice.12 However, the clinical evaluation of KRN7000 was ceased because the released Th1 and Th2 cytokines antagonize each other’s biological effect.13,14 Therefore, improving selectivity in immune responses is highly desirable for the therapeutic use, and many α-GalCer analogues have been designed and synthesized to address this issue.13−15 OCH (2) is an α-GalCer analogue possessing Th2-biased immune response and has therapeutic potential for the treatment of autoimmune diseases.16 The truncated sphingosine backbone in OCH decreases the stability of its binary complex with CD1d and shortens its residence time in the binding pocket of CD1d in APCs, which selectively induces Th2-biased immune response.17 Compared to other immune responses, there are limited studies related to Th17-selective response arising from α-GalCer analogues. Considering that the selective regulation of Th17 response is a promising clinical target for treatment of autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis,18 the development of α-GalCer analogues inducing a selective Th17 response is in high demand, and the systematic structure–activity relationship study between α-GalCer analogues and Th17 response thus should be pursued.

Figure 1.

(a) Chemical structures of representative α-GalCers. (b) Crystal structure of mCD1d complexed with α-GalCer (1) (PDB code: 3HE6). Hydrophobicity map of the binding groove is displayed with key residues.

The crystal structure of mCD1d complexed with 1 elucidated its binding mode (Figure 1b).19,20 The galactose headgroup of 1 is exposed to the outer surface of mCD1d to be recognized by TCR. The sphingosine backbone chain of 1 binds in the F′ pocket, while its acyl chain binds in the A′ pocket. As shown in Figure 1b, both binding grooves, especially the F′ pocket, comprise hydrophobic residues, which indicates that hydrophobic interactions are the critical factors for binding of α-GalCer to CD1d. To date, most of α-GalCer analogues have focused on reinforcing hydrophobic interactions rather than hydrophilic interactions.

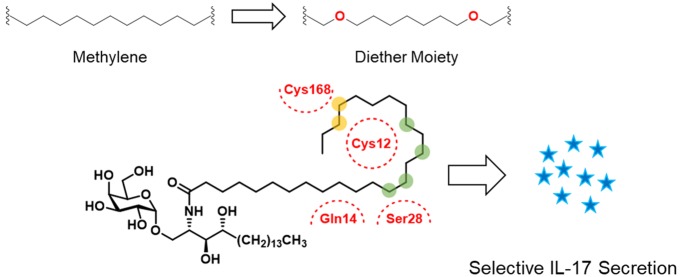

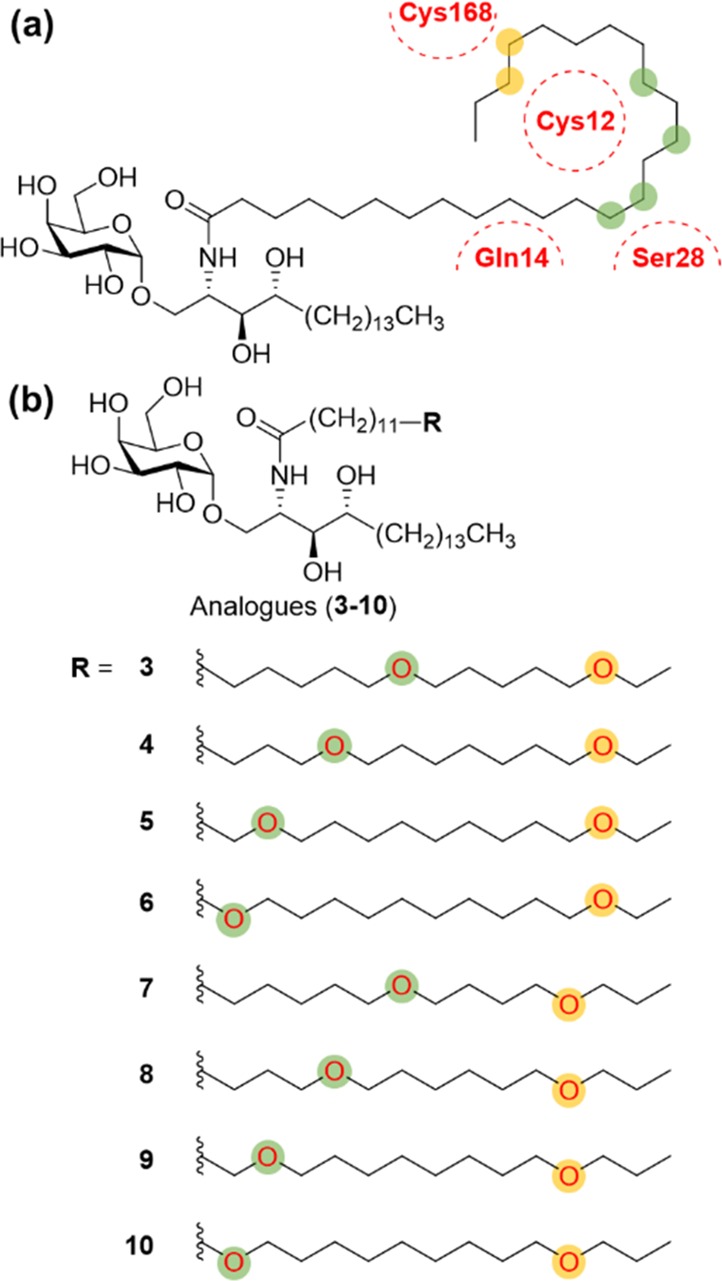

However, the A′ pocket has some hydrophilic residues such as Cys12, Gln14, Ser28, and Cys168 (Figure 1b). To induce hydrophilic noncovalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interaction with these polar residues, the acyl chain of α-GalCer is a proper site for introducing polar functional groups. With this strategy, there are several reports targeting hydrogen-bonding interactions with polar amino acid residues.21−23 Kim et al. introduced the truncated ω-hydroxy acyl chain and showed that hydrogen bonding allowed maintaining the potency compared to 1.21 Herein, we describe the replacement of two methylene groups by two ether moieties in the acyl chain of 1 to establish additional hydrogen-bonding interactions with hydrophilic residues while conserving the conformation of the acyl chain as well as the existing hydrophobic interactions in the A′ pocket. Although there were some cases of introducing ether moiety in the acyl chain, it was not systematically designed to target hydrogen-bonding interactions.24 To design new α-GalCer analogues, we strived to find out the proper positions to replace a methylene unit with oxygen. As shown in Figure 2a, we rationally selected six positions in the acyl chain that are close to the polar residues and can induce hydrogen bonding. To maximize the chances of forming hydrogen-bonding interactions with thiol moieties of the two cysteine residues,25 we introduced the two oxygen atoms at different positions. Positions of oxygen were classified into two groups; green circles that can induce hydrogen-bonding with Cys12 or Ser28, and yellow circles that can interact with Cys168 (Figure 2a). In a combinatorial manner, we designed our novel α-GalCer analogues (3–10) via systematic scanning mutation of two methylene units with two ether moieties (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic design concept of diether-containing α-GalCer analogues. Two oxygens are positioned in the acyl chain, one in green circles and the other in yellow circles. (b) Novel α-GalCer analogues (3–10) containing diether moiety in various locations to induce hydrogen-bonding interaction.

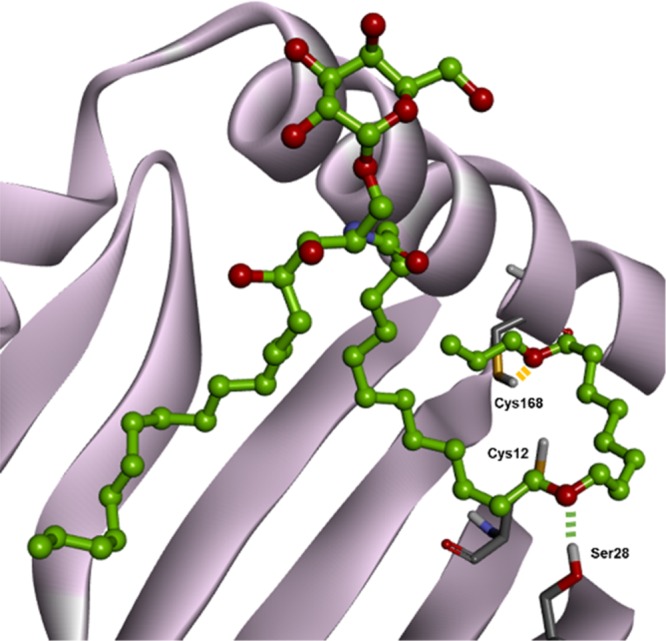

To examine the feasibility of binding events in CD1d, we performed molecular modeling study to find out the interaction modes of 3–10 in the binding pocket of CD1d and compared their docking scores with that of 1. To our pleasant surprise, most of our diether-containing α-GalCer analogues showed higher docking scores than 1, suggesting the improved binding affinity of these α-GalCer analogues with CD1d (Table S1). Moreover, we performed in situ ligand minimization study to find out the optimized conformation of ligands in the binding pocket of CD1d protein. It was predicted that α-GalCer analogue 9 can induce hydrogen-bonding interactions with Ser28 and Cys168 (Figure 3). Other α-GalCer analogues were also predicted to form hydrogen-bonding interactions with Cys12, Ser28, and Cys168 (Figure S1). These hydrophilic noncovalent interactions may influence the stability of the α-GalCer/CD1d binary complex and the subsequent bioactivity such as selective immune responses. Based on these in silico studies, we were confident that our designed α-GalCer analogues are worth to be synthesized and biologically evaluated.

Figure 3.

Optimized binding mode of diether-based α-GalCer analogue 9 within mCD1d via in situ ligand minimization (PDB code: 3HE6). The potential hydrogen-bonding interactions are presented with green and yellow dotted lines.

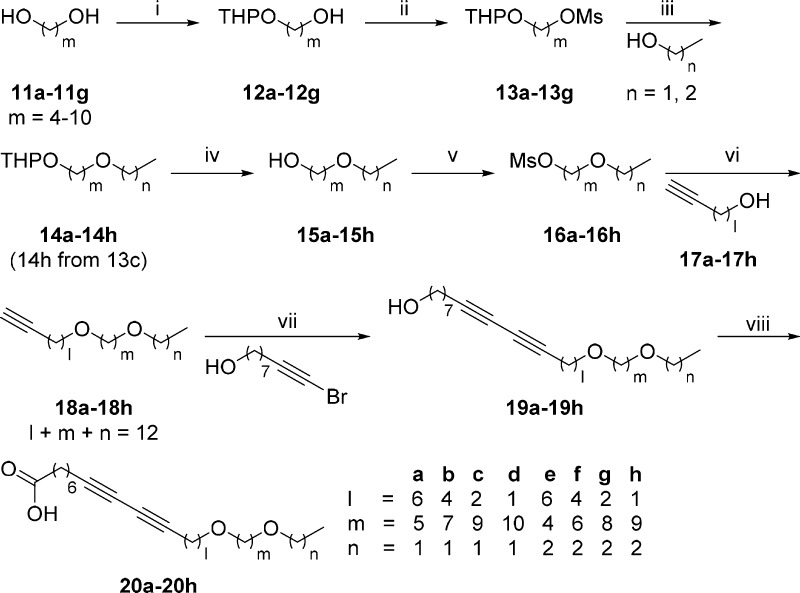

For the preparation of these α-GalCer analogues, acyl chains containing diether moiety were first synthesized (Scheme 1). Starting from commercially available linear alkyl diols (11a–11g), one of the hydroxyl groups was protected with tetrahydropyran (THP) to yield 12a–12g. Then, the other hydroxyl group was mesylated to afford 13a–13g in excellent yields, and the resulting products were substituted with ethanol or propanol to generate 14a–14h. To modify the protected alcohols, the deprotection of THP was conducted via treatment with Dowex50WX4 to get 15a–15h. The free hydroxyl group in 15a–15h was mesylated again to yield 16a–16h, and the resulting mesylates were substituted with 17a–17h to yield 18a–18h. This sequence of chemical transformation allows the preparation of long aliphatic chains with a terminal alkyne moiety to have the identical chain length with different locations of two ether moieties. To extend the chain length of 18a–18h, copper(I)-catalyzed alkyne–alkyne cross-coupling reaction was performed. Due to the identical chain length of 18a–18h, we used 9-bromonon-8-yn-1-ol27 as a counterpart for this cross-coupling reaction and efficiently generated C26 equivalent long chains (19a–19h) with different locations of diether moiety. Finally, Jones oxidation converted primary alcohols 19a–19h to the corresponding carboxylic acids 20a–20h in moderate yields.

Scheme 1. General Synthesis of Diether-containing Long Acyl Chains.

Reagents, conditions, and yields: (i) 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran, pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate, THF/CHCl3 (1:1, v/v), r.t., overnight, 41–51%; (ii) MsCl, TEA, THF, 0 °C to r.t., 1 h, 96% to quantitative; (iii) NaH, DMF, 0 °C to r.t., 2 h, 75–97%; (iv) Dowex 50WX4, MeOH, overnight, 64–97%; (v) MsCl, TEA, THF, 0 °C to r.t., 1 h, 98% to quantitative; (vi) NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 4 h, 29–90%; (vii) CuCl, PPh3, NH2OH·HCl, 30% n-BuNH2(aq.), r.t., overnight, 27–75%; (viii) Jones reagent, acetone, 0 °C, 2 h, 48–96%.

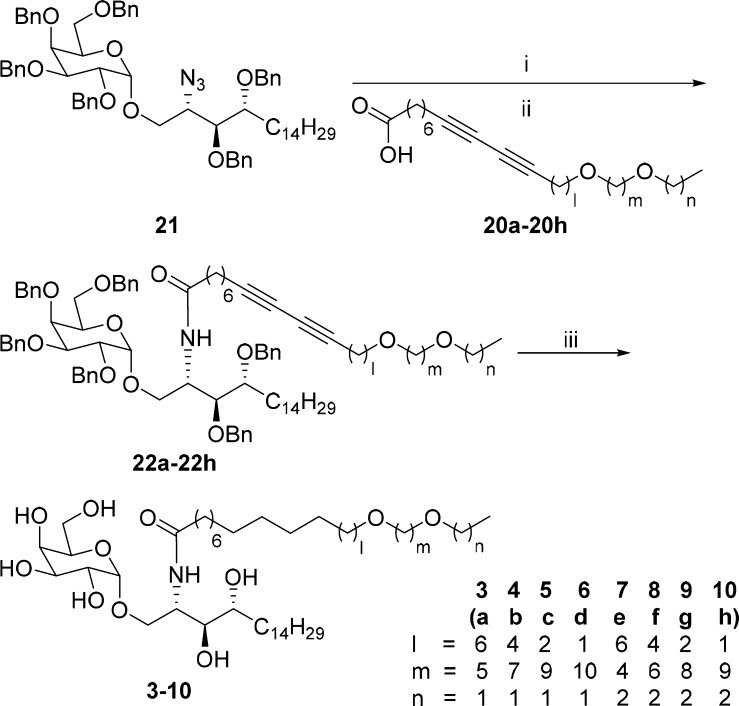

The assembly of an α-galactosyl sphingosine part (21)26 with a series of acyl chains (20a–20h) provided final α-GalCer analogues (Scheme 2). First, azide in 21 was reduced to amine via Staudinger reduction, and its EDC-mediated amide coupling with acyl chains 20a–20h produced 22a–22h in moderate two-step yields. As a final step, the global debenzylation and alkyne reduction via catalytic hydrogenation using Pd(OH)2/C transformed 22a–22h to the desired α-GalCer analogues (3–10) as white solids.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of α-GalCer Analogues 3–10.

Reagents, conditions, and yields: (i) PPh3, benzene/H2O (100:1, v/v), 60 °C, 5.5 h; (ii) EDC·HCl, DMAP, THF, r.t., overnight, 50–75%, two-step yields; (iii) H2, Pd(OH)2/C, MeOH/DCM (3:1, v/v), r.t., 8 h, 64% to quantitative yield.

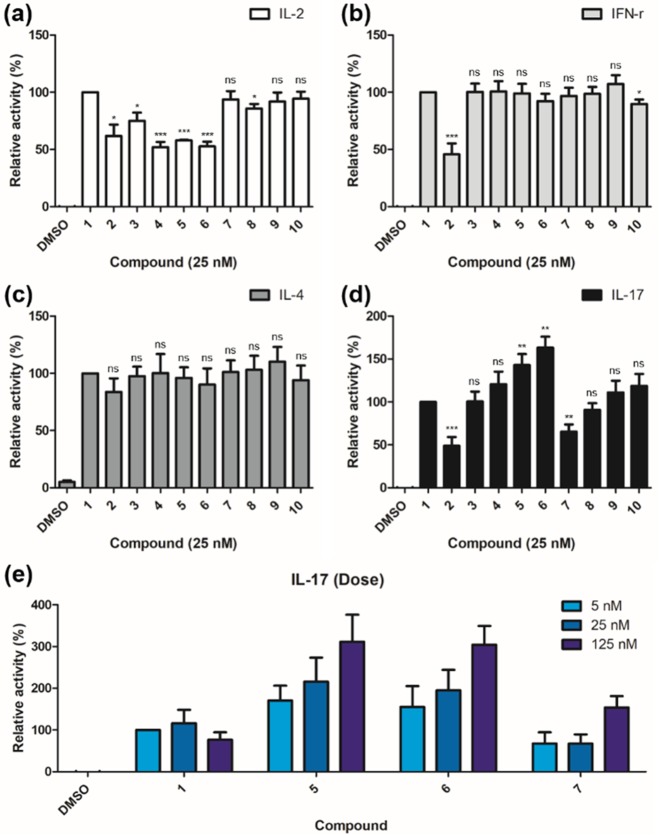

The biological activities of α-GalCer analogues (3–10) with diether moiety were evaluated using ELISA assay in mouse hepatic mononuclear cells (HMNCs). As shown in Figure 4a, 3–6 showed less IL-2 secretion than 7–10 and 1. This observation confirmed that the position of diether moiety influences IL-2 secretion, which is an indicator of iNKT cell activation upon engagement of α-GalCer analogues in CD1d, especially depending on the position of second oxygen at either C23 or C24 position of acyl chain. In comparison with 1, 3–10 induced similar amounts of IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion (Figure 4b,c). From this result, we confirmed that hydrophobic interaction is important for inducing Th1 and Th2 responses, and diether moiety was not effective for selectively perturbing Th1 and Th2 responses. However, 3–10 indicated clear structure–activity relationship for IL-17 secretion (Figure 4d). From the IL-17 levels induced by 3–10, it was inferred that increasing the distance between the two oxygens led to more IL-17 secretion. In addition, α-GalCer analogues containing oxygen at the C23 position of acyl chain (7–10) showed less IL-17 secretion than the analogues containing oxygen at the C24 position (3–6). Especially, with statistical significance, 5 and 6 induced the most increased IL-17 secretion, while 7 induced the most reduced IL-17 secretion. Among 5–7, 5 and 6 showed dose dependency for IL-17 secretion (Figure 4e). This observation suggests that α-GalCer analogues 5 and 6 may lead to a potential protective effect toward infections against pathogens, whereas α-GalCer analogue 7 may induce anti-inflammatory effects. It is worth mentioning that observed IL-17 secretion patterns have some correlations with docking scores calculated during our initial design stage (see Table S1). α-GalCer analogues with higher docking scores have higher IL-17 secretion, but this observation should be further evaluated with structural information.

Figure 4.

Biological evaluations of compounds 1–10. Data are shown as mean ± SEM for relative activity. (a) IL-2 secretion from mouse hepatic mononuclear cells (HMNCs) was measured after 24 h upon treatment of α-GalCer analogues (n = 3 biological replicates). (b) IFN-γ, (c) IL-4, and (d) IL-17 secretion from mouse HMNCs were measured after 72 h upon treatment of α-GalCer analogues (n = 5 biological replicates). (e) IL-17 secretion from mouse HMNCs stimulated by 5, 25, and 125 nM of 1 and α-GalCer analogues, which showed statistical significance in (d) (n = 5 biological replicates). Statistically significant differences are indicated: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. ns, not significant.

In conclusion, we rationally designed novel α-GalCer analogues with a diether moiety in the acyl chain, which can induce additional hydrogen-bonding interactions with Cys12, Ser28, and Cys168 while retaining hydrophobic interaction in the A′ pocket of CD1d in APCs. This led us to synthesize a series of α-GalCer analogues (3–10). In vitro biological evaluations using an ELISA assay in HMNCs indicated that our α-GalCer analogues have similar cytokine secretions as 1, except for IL-17. The selective secretion patterns of IL-17 cytokine were observed with statistical significance for 5–7. Among them, α-GalCer analogues 5 and 6 showed the most increased IL-17 secretion, which may indicate a protective effect against pathogen, while 7 induced the most reduced IL-17 secretion, suggesting anti-inflammatory effect.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- iNKT

invariant natural killer T

- α-GalCer

α-galactosylceramide

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- Th1

T helper 1

- Th2

T helper 2

- Th17

T helper 17

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL

interleukin

- mCD1d

mouse CD1d

- THP

tetrahydropyran

- r.t.

room temperature

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- Ms

methanesulfonyl

- TEA

triethylamine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- DCM

dichloromethane

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HMNC

hepatic mononuclear cells

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00556.

Detailed synthetic procedure, spectroscopic data and full characterizations of all new compounds, and procedures for biological experiments including ELISA assay(PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ Memory Division, Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Hwaseong-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea.

Author Contributions

§ These authors contributed equally. Y.S.H. and H.S. prepared the manuscript, performed in silico study, and synthesized all compounds used in this study. J.Y. performed biological evaluation. S.B.P. directed the study in all aspects of the experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors critically review the text and figures.

This work was supported by the Creative Research Initiative Grant (2014R1A3A2030423) and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (2012M3A9C4048780) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (Ministry of Science & ICT). Y.S.H. and H.S. are grateful for the fellowship by BK21 Plus Program.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Taniguchi M.; Harada M.; Kojo S.; Nakayama T.; Wakao H. The regulatory role of Vα14 NKT cells in innate and acquired immune response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 21, 483–513. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda J. L.; Mallevaey T.; Scott-Browne J.; Gapin L. CD1d-restricted iNKT cells, the “swiss-army knife” of the immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 358–368. 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. J.; Brigl M.; Brenner M. B. Invariant Natural Killer T Cells: An innate activation scheme linked to diverse effector functions. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 101–117. 10.1038/nri3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey D. I.; MacDonald H. R.; Kronenberg M.; Smyth M. J.; Van Kaer L. NKT cells: What’s in a name?. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 231–237. 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendelac A.; Savage P. B.; Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 297–336. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossjohn J.; Pellicci D. G.; Patel O.; Gapin L.; Godfrey D. I. Recognition of CD1d-restricted antigens by natural killer T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 845–857. 10.1038/nri3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc D. M.; Girardi E. Recognition of microbial glycolipids by natural killer T cells. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 400. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K. M.; Reiner S. L. The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 933–944. 10.1038/nri954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L. A Brief History of Th17, The first major revision in the Th1/Th2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 139–145. 10.1038/nm1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver C. T.; Elson C. O.; Fouser L. A.; Kolls J. K. The Th17 pathway and inflammatory diseases of the intestines, lungs, and skin. Annu. Rev. Pathol.: Mech. Dis. 2013, 8, 477–512. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M.; Motoki K.; Akimoto K.; Natori T.; Sakai T.; Sawa E.; Yamaji K.; Koezuka Y.; Kobayashi E.; Fukushima H. Structure-activity relationship of α-galactosylceramides against B16-bearing mice. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 2176–2187. 10.1021/jm00012a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T.; Cui J.; Koezuka Y.; Toura I.; Kaneko Y.; Motoki K.; Ueno K.; Nakagawa R.; Sato H.; Kondo E.; Koseki H.; Taniguchi M. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of Vα14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science 1997, 278, 1626–1629. 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage P. B.; Teyton L.; Bendelac A. Glycolipids for natural killer T cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 771–779. 10.1039/b510638a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchet-Cadeddu A.; Hénon E.; Dauchez M.; Renault J. H.; Monneaux F.; Haudrechy A. The stimulating adventure of KRN7000. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 3080–3104. 10.1039/c0ob00975j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent X.; Bertin B.; Renault N.; Farce A.; Speca S.; Milhomme O.; Millet R.; Desreumaux P.; Hénon E.; Chavatte P. Switching invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell response from anticancerous to anti-inflammatory effect: Molecular Bases. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5489–5508. 10.1021/jm4010863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K.; Miyake S.; Yamamura T. A synthetic glycolipid prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing TH2 bias of natural killer T cells. Nature 2001, 413, 531–534. 10.1038/35097097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy C.; Shepherd D.; Fleire S.; Stronge V. S.; Koch M.; Illarionov P. A.; Bossi G.; Salio M.; Denkberg G.; Reddington F.; Tarlton A.; Reddy B. G.; Schmidt R. R.; Reiter Y.; Griffiths G. M.; Van Der Merwe P. A.; Besra G. S.; Jones E. Y.; Batista F. D.; Cerundolo V. The length of lipids bound to human CD1d molecules modulates the affinity of NKT cell TCR and the threshold of NKT cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 1131–1144. 10.1084/jem.20062342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellner H. Targeting interleukin-17 in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: rationale and clinical potential. Ther. Adv. Musculoskeletal Dis. 2013, 5, 141–152. 10.1177/1759720X13485328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicci D. G.; Patel O.; Kjer-Nielsen L.; Pang S. S.; Sullivan L. C.; Kyparissoudis K.; Brooks A. G.; Reid H. H.; Gras S.; Lucet I. S.; Koh R.; Smyth M. J.; Mallevaey T.; Matsuda J. L.; Gapin L.; McCluskey J.; Godfrey D. I.; Rossjohn J. Differential recognition of CD1d-α-galactosyl ceramide by the Vβ8.2 and Vβ7 semi-invariant NKT T cell receptors. Immunity 2009, 31, 47–59. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel O.; Pellicci D. G.; Uldrich A. P.; Sullivan L. C.; Bhati M.; McKnight M.; Richardson S. K.; Howell A. R.; Mallevaey T.; Zhang J.; Bedel R.; Besra G. S.; Brooks A. G.; Kjer-Nielsen L.; McCluskey J.; Porcelli S. A.; Gapin L.; Rossjohn J.; Godfrey D. I. Vβ2 natural killer T cell antigen receptor-mediated recognition of CD1d-glycolipid antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 19007–19012. 10.1073/pnas.1109066108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C.; Kim J. H.; Baek D. J.; Lee J. Y.; Cho M.; Lee Y. S.; Kang C. Y.; Chung D. H.; Cho W. J.; Kim S. Design and evaluation of ω-hydroxy fatty acids containing α-GalCer analogues for CD1d-mediated NKT cell activation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 331–335. 10.1021/ml400517b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inuki S.; Aiba T.; Hirata N.; Ichihara O.; Yoshidome D.; Kita S.; Maenaka K.; Fukase K.; Fujimoto Y. Isolated polar amino acid residues modulate lipid binding in the large hydrophobic cavity of CD1d. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 3132–3139. 10.1021/acschembio.6b00674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inuki S.; Kashiwabara E.; Hirata N.; Kishi J.; Nabika E.; Fujimoto Y. Potent Th2 cytokine bias of natural killer T cell by CD1d glycolipid ligands: Anchoring effect of polar groups in the lipid component. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 9655–9659. 10.1002/anie.201802983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma Y. K.; Reddy B. S.; Pawar M. S.; Bhunia D.; Sampath Kumar H. M. Design, synthesis, and immunological evaluation of benzyloxyalkyl-substituted 1,2,3-triazolyl α-GalCer analogues. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 172–176. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Zajonc D. M.; Fujio M.; Sullivan B. A.; Kinjo Y.; Kronenberg M.; Wilson I. A.; Wong C. H. Design of natural killer T cell activators: structure and function of a microbial glycosphingolipid bound to mouse CD1d. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 3972–3977. 10.1073/pnas.0600285103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai S.; Sedigh-Zadeh R.; waser J. Pd(0)-catalyzed alkene oxy- and aminoalkynylation with aliphatic bromoacetylenes. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 3783–3801. 10.1021/jo400254q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G. T.; Pan Y. S.; Lu K. C.; Cheng Y. P.; Lin W. C.; Lin S.; Lin C. H.; Wong C. H.; Fang J. M.; Lin C. C. Synthesis of α-galactosyl ceramide and the related glycolipids for evaluation of their activities on mouse splenocytes. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 1855–1862. 10.1016/j.tet.2004.12.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.