Abstract

Background and Aim

Ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury frequently occurs in different situations. Female sex hormones have a protective function. The purpose of this study was to determine the function of female sexual hormones on the gastric damage induced by I/R in male rats.

Methods

Forty (40) Wistar rats were randomized into five groups: intact, ischemia- reperfusion (IR), IR + estradiol (1mg/kg), IR + progesterone (16 mg / kg) and IR + combination of estradiol (1mg / kg) and progesterone (16 mg/ kg). Before the onset of ischemia and before reperfusion all treatments were done by intraperitoneal (IP) injection. After animal anesthesia and laparotomy, celiac artery was occluded for 30 minutes and then circulation was established for 24 hours. Results expressed as mean ± SEM and P <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The Glutathione (GSH) concentration significantly decreased after induction of gastric IR (P<0.001). Estradiol (P<0.001) and combined estradiol and progesterone (P<0.001) significantly increased GSH levels. The myeloperoxidase (MPO) concentration significantly increased after induction of gastric IR (P<0.001). Different treatments significantly reduced MPO levels (P<0.001). The gastric acid concentration significantly increased after induction of gastric IR (P<0.001). Treatment with estradiol, progesterone (P<0.05) and combined estradiol and progesterone (P<0.01) significantly reduced gastric acid levels. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) concentration decreased after induction of gastric IR. The SOD levels were not significant.

Conclusion

These data suggested that female sexual steroids have a therapeutic effect on gastrointestinal ischemic disorders by reduction of MPO and gastric acid, and increasing gastric GSH & SOD levels following gastric IR.

Keywords: Gastric ischemia–reperfusion, estradiol, Progesterone, GSH, SOD, MPO, Gastric Acid

INTRODUCTION

Various medical opinions are used to explain gastric ischemia. Gastric ischemia is rare because of the rich collateral blood supply to the stomach (1). There are several terms to explain gastric ischemia including; gastric infarction or apoplexy, gastric necrosis, moribund stomach, stress ulceration, chronic ischemic gastritis and gastropathy (2). It is known that many hemorrhagic conditions such as peptic ulcer bleeding, hemorrhagic shock, vascular rupture and surgery lead to gastric ischemia– reperfusion (GI-R) (3, 4).

GI-R leads in turn to gastric mucosal injury, it can repair the damage quickly, suggesting that the stomach might autoregulate gastric mucosal cellular apoptosis and proliferation (5-7).

Fukuyama et al. (5) reported that apoptosis is not induced in the gastric mucosa after GI-R, but Wada et al. (7) demonstrated that GI-R induced significant apoptosis in the gastric mucosa. Reduced cAMP generation, inhibition of ATPase activity in mitochondria, activation of oxygen-free radicals, dysfunction of microcirculation, aggregation of leukocytes, intracellular acidosis, and gastric acid effects have all been proposed to be involved in GI-R injury (7-11). The celiac artery (or the celiac trunk) provides oxygenated blood to the foregut: it supplies blood to the stomach, the liver, the spleen and the part of the esophagus that reaches the abdomen (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Vascular supply and network of the stomach.a., artery; v., vein (2).

The celiac artery is the first major branch of the abdominal aorta, and it further branches into the splenic artery, left gastric artery and the general hepatic artery. A small esophageal branch takes off the left gastric artery close to the gastric cardia and the main left gastric artery arches over the proximal lesser curvature (2).

Castañeda et al. (12) observed that the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) I/R injury caused significant accumulation of gastric luminal fluid that was alkaline and rich in protein, glucose, and bicarbonate content when compared with sham controls. SMA I/R injury also caused gastric surface epithelial cell injury and significantly increased serum and antral gastrin levels (12).

There is a gender difference in the occurrence of gastric cancer with a 2:1 men to premenopausal women ratio (13). Some studies have evaluated the effects of estradiol (E2) and progesterone on gastric cancer cell lines, gastric ulcerations, and chemical gastric carcinogenesis, and reported hormonal effects after short time treatments (14, 15). A previous study showed that the prescription of E2 to rats with ulcers induced by different methods (chemical, stress, pyloric shay) exerted an antiulcerative effect, increased parietal cells action and gastrin secretion, and maintained mucosa integrity (14). Furthermore, the treatment with E2 in male rats reduced the carcinogenic effect and increased both mucin and gastrin secretion in the antral mucosa (14).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the protective role of female sexual hormones on gastric tissue following gastric ischemia-reperfusion in male rats and antioxidant enzyme activity such as SOD, GSH, MPO and Gastric acid level as an indicator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

In this study, 40 male Wistar rats (200–250 g body weight) were obtained from the animal house of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, maintained under standard conditions (12 h light/dark cycle; 25±3°C, 45–65% humidity) and had free access to standard rat feed and water ad libitum. All the animals were acclimatized to laboratory conditions for a week before commencement of the experiment. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the ethics committee of the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Animal grouping and surgical procedures

Forty rats were randomly divided into one of five groups (n = eight per group) and in each group, were evaluated the gastric SOD, GSH, MPO levels and gastric acid level. Estradiol, progesterone and their solvents were purchased from Aburaihan Pharmaceutical Company (Iran).

Animals were randomly assigned in different groups:

1. Sham group: intact male rats;

2. Ischemia- reperfusion (IR) group: Ischemia was for 30 minutes and then reperfusion for 24 hours.

3. Estradiol (1 mg/kg) group (E2): estradiol with a dose of 1 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection (16).

4. Progesterone (16 mg/kg) group (P): progesterone with a dose of 16 mg/kg intraperitoneal (17).

5. Combination of estradiol (1 mg / kg) and progesterone (16 mg/kg) group: combination of estradiol with a dose of 1 mg/kg and progesterone with dose of 16 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection (16, 17).

All of treatments were done before the onset of ischemia and before reperfusion by intraperitoneal (IP) injection method.

Preparation of the gastric ischemia–reperfusion model

The rats were anesthetized with Thiopental (50 mg/kg, i.p.). The celiac artery and its adjacent tissues were carefully separated. The celiac artery was clamped using a ligature for 30 min to induce ischemia, and the ligature was then removed to allow reperfusion for 24 hours (18).

Determination of gastric GSH contents

The analysis is based on the reaction between sulfhydryl groups with 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB). Proteins were precipitated using 10% TCA, centrifuged and 0.5 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) and 10 mM DTNB. Then this combination was incubated for 10 min and the absorbance was measured at 412 nm against appropriate blank (19).

Assessment of MPO activity

The gastric tissue (principally the body) was centrifuged at 800×g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded. 10 mL of ice-cold 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide and 10 mMEDTA was then added to the pellet. It was then subjected to one cycle of freezing, thawing and brief period (15s) of sonication. After sonication, the solution was centrifuged at 13,100×g for 20 min. The MPO activity was measured spectrophotometrically (20). A measured volume (0.1 mL) of supernatant was combined with 2.9 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer containing 0.167 mg/mL of O-dianisidine hydrochloride and 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide. The change in absorbance was measured at 460 nm. One unit of MPO activity is defined as the change in absorbance per min by 1.0 at room temperature, in the final reaction. It was calculated by using the following formula

MPO activity (U/g) = X/weight of the piece of tissue taken where X=10×change in absorbance per min/volume of supernatant taken in the final concentration.

Determination of SOD activity

The method of Sun et al. (21) as described by Prasad et al. was used for measuring SOD activity in the tissue. The assay mixture contained (per litre): xan- thine (0.1 mmol), BSA (50 mg), diethylenetriamine- penta-acetic acid (1 mmol), nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT, 25 pmol), sodium carbonate (40 mmol, pH 10.2), disodium salt of bathocuproine-disulphonic acid (250 pmol). The mixture was vortexed and 2.45 mL was added to each tube. For the determination of Mn- SOD, NaCN (5 mmol) was included in the reaction mixture to inhibit Cu-Zn-SOD. Water was added to the blank and reagent blank tubes (0.5 and 0.55 mL respectively). Ten to five-hundred microlitres of sample were added to assay tubes. Fifty microlitres of xanthine oxidase (20 units/mL) were added to each tube, except to the reagent blank, at an interval of 20 s to start the reaction. The final volume of the reaction mixture was 3 mL. After incubation at 25 °C for 20 min, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 mL of 0.8 mmol/L cupric chloride. The formazan produced was measured spectrophotometrically at 560 nm. Blank reading (without sample) was taken as 100%. The percentage inhibition of NBT by sample was calculated and it was plotted against the protein content of the sample. From this plot, the value of SOD was calculated in terms of units defined as the amount of SOD that inhibits the reduction of NBT by 50%. Cu-Zn-SOD activity was calculated by subtracting the value in the sample with NaCN (Mn-SOD) from the value obtained in the absence of NaCN (total SOD). The SOD activity as an inhibition activity and the results were expressed as SOD nmol/g protein.

Gastric acid measurement

In all groups, 1 mL normal saline was introduced into the stomach. After 15 min, another 1 mL normal saline was injected into the stomach. A period of 30 min was allowed for stabilization; once the gastric acid secretion had been stable for 30 min, it was considered as basal acid secretion. Throughout the experiment, the gastric secretions were collected in consecutive 15- min intervals (2 samples). The acid content of each gastric washout sample was measured with a manual titrator pH meter to an end point pH of 7 with 0.01 N NaOH and mean of samples expressed as mEq/mL/15min (22).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± SEM. The statistical analysis was carried out by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All calculations were performed with SPSS 15 for Windows, and P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

As mentioned before, the purpose of this study was to determine the function of female sex hormones, and their combination in protecting the induced gastric damage.

GSH concentration changes in different groups

Figure 2 shows the gastric GSH contents, in different groups of study. The gastric GSH level in I/R group (3.4 ± 1.09 μmol/g) was significantly (P<0.001) decreased compared to the intact group (20 ± 3.8μmol/g). After the treatment with E2 and E2+P, the amount was significantly increased to 47.56 ± 1.89μmol/g(P<0.001) and 24.39 ± 3.64μmol/g (P<0.001).

Figure 2.

GSH activity (μmol/g) in gastric tissue, following treatment of gastric I/R with either progesterone and estradiol. Statistical comparison was performed using one way ANOVA. P value <0.05 was considered significant. ***: P<0.001 vs. E2 = Estradiol; P = Progesterone.

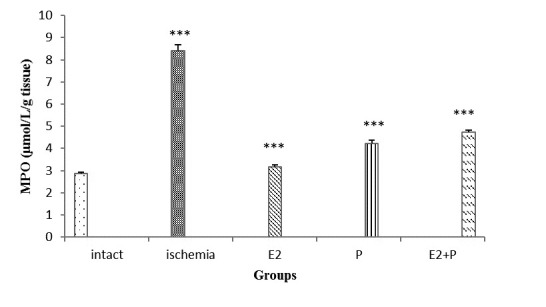

MPO concentration changes in different groups

Figure 3 shows the gastric MPO contents in different groups of study. As shown in Figure 3, the amount of MPO contents in I/R (8.42 ± 0.26μmol/L/g tissue) (P<0.001) significantly increased compared to intact groups (2.85 ± 0.09μmol/L/g tissue). After E2, P and E2+P treatment, the MPO levels significantly reduced to 3.18 ± 0.07μmol/L/g tissue (P<0.001), 4.23 ± 0.13μmol/L/g tissue.

Figure 3.

MPO activity (μmol/L/g tissue) in gastric tissue, following treatment of gastric I/R with either progesterone and estradiol. Statistical comparison was performed using one way ANOVA. Differences with P value <0.05 were considered significant. ***: P<0.001 vs. ischemia group.

SOD concentration changes in different groups

Figure 4 shows the SOD activity in different groups of study. As shown in Figure 4, the SOD activity was increased after treatment in comparison with I/R group, but these results were not significant. The SOD level in I/R group (0.29 ± 0.06 nM/g) also decreased, compared to the intact group (0.17 ± 0.06 nM/g). After the treatment with E2 (0.29 ± 0.07 nM/g), P (0.19 ± 0.02 nM/g), and E2+P (0.26 ± 0.06 nM/g), the amount was increased.

Figure 4.

SOD activity (nM/g) in gastric tissue, following treatment of gastric I/R with either progesterone and estradiol. Statistical comparison was performed using one way ANOVA. No significant differences were found in SOD activity.

Gastric acid concentration changes in different groups

Figure 5 shows the gastric acid secretion, in different groups of study. The gastric acid content was increased in I/R group (6.61±1.08 mEq/min) compared to intact group (2.44±0.49mEq/min). These levels significantly reduced after treatment with E2, P and E2+P in comparison to intact group (P<0.05).

Figure 5.

Gastric acid levels (mEq/15min) in intact rats, I/R and treated rats. Statistical comparison was performed using one way ANOVA. Differences with P value <0.05 were considered significant. ***: P<0.001 vs. ischemia group.* : P<0.05 vs. IR group.

DISCUSSION

As previously mentioned, many hemorrhagic conditions, such as hemorrhagic shock, peptic ulcer bleeding, vascular rupture, and surgery, lead to gastric ischemia– reperfusion (GI-R) (3, 4). In chronic gastric ischemia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, overt or occult GI bleeding, anemia, diarrhea, and weight loss can be present (2). Also GI-R leads in turn to gastric mucosal injury. Ischemia-reperfusion causes gastric mucosal lesions, at least in part, due to the formation of oxygen radicals (23-25). Studies have shown that reactive oxygen metabolites and lipid peroxidation play important roles in ischemia-reperfusion injury in many organs such as the heart, brain and stomach. In one study, the results indicated that the lesion index and the formation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances increased significantly with the ischemia-reperfusion injury in the gastric mucosa and L-carnitine treatment reduced these parameters to the values of sham operated rats (26). In our study, we examined the effect of progesterone and estradiol on four important factors (GSH, MPO, SOD, gastric acid) after I/R.

In one study, they found that apoptosis induced by I/R was different between the gastric mucosa and the intestinal mucosa. IR following the occlusion of the celiac artery did not induce apoptosis in the rat gastric mucosa, but in the case of the superior mesenteric artery it did induce apoptosis in the small intestinal mucosa (2). Previous studies have shown that the gastric cancer incidence has a male to premenopausal women ratio of approximately 2:1 (13). Research suggests that sexual steroids play a role in oxidative stress. The antioxidant enzymes activity varies during the menstrual cycle as sexual steroids concentration changes.

The results of our survey showed that the GSH concentration significantly decreased after induction of gastric ischemia – reperfusion (Fig. 2). Treatment with estradiol and combined estradiol and progesterone significantly increased GSH levels. But treatment with progesterone was not significant. Studies show that GSH is involved in the synthesis and repair of DNA, assists the recycling of vitamins C and E, blocks free radical damage, enhances the antioxidant activity of vitamin C, facilitates the transport of amino acids and plays a critical role in detoxification (27).

There are some studies evaluating the effects of E2 and P on gastric cancer cell lines, gastric ulcerations, and chemical gastric carcinogenesis, reporting hormonal effects after short term treatments (14, 15). A more intense and extended acute inflammatory response was observed in the groups treated with E2, whereas the P-treated animals presented a lower incidence of high-grade acute gastritis when compared to the E2 group.

In this study, it was observed that the MPO concentration significantly increased after induction of gastric ischemia - reperfusion. Treatment with estradiol, progesterone and combined estradiol and progesterone significantly reduced Myeloperoxidase levels. Myeloperoxidase is an enzyme present in neutrophils and at a much lower concentration in monocytes and macrophages. The level of MPO activity is directly proportional to the neutrophil concentration in the inflamed tissue. In addition, increased MPO activity has been reported to be an index of neutrophil infiltration and inflammation (28).

On the basis of our study, it was shown that changes of SOD levels were not significant. The controversy results were shown in different papers and we mention some of them. SOD levels are less in male rats than in female ones (29). Female sexual hormones modulate the SOD activity and SOD activity decreases in ovariectomized rats. The SOD activity is higher in females than in males because of high estradiol concentration (30). Aggarwal and colleagues suggested that progesterone had an important effect on the activity of all antioxidants and exerts its protection effect by this function (31). SOD activity is increased in human endometrial tissue by progesterone (32). On the other hand, Pajovic and colleagues showed that SOD activity is reduced by progesterone in ovariectomized rats (33). Progesterone does not have any effect on the SOD activity in pancreatic cells. Thus we can conclude that the action of progesterone is different and many factors will be affected by it.

As was observed in the results, the gastric acid concentration significantly increased after induction of gastric ischemia - reperfusion. Treatment with estradiol, progesterone (P<0.05) and combined estradiol and progesterone significantly reduced gastric acid levels. Because human duodenal mucosal bicarbonate secretion (DBMS) protects duodenum against acid-peptic injury, Smith et al. (16), hypothesize that estrogen stimulates DBMS. They found that basal and acid-stimulated DBMS responses were 1.5 and 2.4-fold higher in female than in male mice in vivo. In this study acid-stimulated DBMS in both genders was abolished by ICI 182,780 and tamoxifen (16).

Hyperglycemia and hyper glucagonemia in addition to other peptide hormones such as gastric inhibitory peptide can inhibit gastric acid secretion (34) or cause gastric mucosal atrophy due to diabetic autonomic neuropathy (35). It has been indicated that in diabetic rats, the secretory rate of histamine-stimulated gastric H+ was significantly reduced, whereas the mucus secretion was increased (36).

According to our study, protective effects of estrogen and progesterone upon gastric tissue following gastric ischemia-reperfusion, female sex steroids can be used to reduce gastrointestinal ischemic disorders.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The study was financially supported by a research grant from North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran.

References

- 1.Lanciault G, Jacobson ED. The gastrointestinal circulation. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:851–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang SJ, Daram SR, Wu R, Bhaijee F. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management of Gastric Ischemia. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mythen MG, Webb AR. Intra-operative gut mucosal hypoperfusion is associated with increased post-operative complications and cost. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20:99–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01707662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swank GM, Deitch EA. Role of the gut in multiple organ failure: bacterial translocation and permeability changes. World J Surg. 1996;20:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s002689900065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuyama K, Iwakiri R, Noda T, Kojima M, Utsumi H, Tsunada S, Sakata H, Ootani A, Fujimoto K. Apoptosis induced by ischemia–reperfusion and fasting in gastric mucosa compared to small intestinal mucosa in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:545–549. doi: 10.1023/a:1005695031233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naito Y, Mizushima K, Yoshikawa T. Global analysis of gene expression in gastric ischemia–reperfusion: a future therapeutic direction for mucosal protective drugs. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(Suppl 1):S45–55. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2806-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wada K, Nakajima A, Takahashi H, Yoneda M, Fujisawa N, Ohsawa E, Kadowaki T, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Matsuhashi N, Saubermann LJ, Nakajima N, Blumberg RS. Protective effect of endogenous PPARgamma against acute gastric mucosal lesions associated with ischemia–reperfusion. Am J PhysiolGastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G452–458. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00523.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang JF, Zhang YM, Yan CD, Zhou XP. Neuroregulative mechanism of hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus on gastric ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats. Life Sci. 2002;71:1501–1510. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01850-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villegas I, Martin AR, Toma W, de la Lastra CA. Rosiglitazone, an agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, protects against gastric ischemia–reperfusion damage in rats: role of oxygen free radicals generation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;505:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brzozowski T, Konturek PC, Konturek SJ, Drozdowicz D, Kwiecieñ S, Pajdo R, Bielanski W, Hahn EG. Role of gastric acid secretion in progression of acute gastric erosions induced by ischemia–reperfusion into gastric ulcers. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii M, Shimizu S, Nawata S, Kiuchi Y, Yamamoto T. Involvement of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide in gastric ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats: protective effect of tetrahydrobiopterin. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:93–98. doi: 10.1023/a:1005413511320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castañeda A, Vilela R, Chang L, Mercer DW. Effects of intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury on gastric acid secretion. J Surg Res. 2000;90(1):88–93. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stemmermann GN, Nomura AMY, Kolonel LN, Goodman MT, Wilkens LR. Gastric carcinoma, pathology findings in a multiethnic population. Cancer. 2002;95:744–750. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell-Thompson M, Lauwers GY, Reyher KK, Cromwell J, Shiverick KT. 17 beta-estradiol modulates gastroduodenal pre-neoplastic alterations in rats exposed to the carcinogen N-methyl-N’-nitro-N nitrosoguanidine. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4886–4894. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.10.7030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguwa CN. Effects of exogenous administration of female sex hormones on gastric secretion and ulcer formation in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;104:79–84. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith A, Contreras C, Ko KH, Chow J, Dong X, Tuo B, Zhang HH, Chen DB, Dong H. Gender-specific protection of estrogen against gastric acid-induced duodenal injury: stimulation of duodenal mucosal bicarbonate secretion. Endocrinology. 2008;149(9):4554–4566. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen G, Shi J, Ding Y, Yin H, Hang C. Progesterone prevents traumatic brain injury-induced intestinal nuclear factor kappa B activation and proinflammatory cytokines expression in male rats. Mediators Inflamm. 2007;10:1155–1162. doi: 10.1155/2007/93431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gemici B, Tan R, Ongüt G, Izgüt-Uysal VN. Expressions of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in gastric ischemia-reperfusion: role of angiotensin II. J Surg Res. 2010;161:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.07.018. 1; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moran A, Depierre JW, Mannervick B. Levels of glutathione, glutathione reductase, glutathione-S-transferase activities in rat liver. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1979;582:67–68. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krawisz JE, Sharon P, Stenso WF. Qualitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1344–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Y, Oberley LW, Li Y. A simple method for clinical assay of superoxide dismutase. Clin. Chem. 1988;34(3):497–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rafsanjani FN, Shahrani M, Ardakani ZV, Ardakani MV. Marjoram increases basal gastric acid and pepsin secretions in rat. Phytotherapy Research. 2007;21(11):1036–1038. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh M, Guth PH. Role of oxygen-derived free radicals in hemorrhagic shock-induced gastric lesions in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1162. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawashi T, Joh T, Iwata F, Itoh M. Gastric epithelial damage induced by local ischemia-reperfusion with or without exogenous acid. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;226:G263. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.2.G263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith GS, Mercer DW, Cross JM, Barreto JC, Miller TA. Gastric injury induced by ethanol and ischemia-reperfusion in the rat: differencing peroxidation and oxygen radicals. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1996;41:1157. doi: 10.1007/BF02088232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derin N, Izgut-Uysal VN, Agac A, Aliciguzel Y, Demir N. L-carnitine protects gastric mucosa by decreasing ischemia-reperfusion induced lipid peroxidation. J PhysiolPharmacol. 2004;55(3):595–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavan S, Sava L, Saxena V, Pillai S, Sontakke A, Ingole D. Reduced glutathione: importance of specimen collection. Indian J. Clin.Biochem. 2005;20:150–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02893062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choudhary S, Keshavarzian A, Yong M, Wade M, Bocckino S, Day BJ, Banan A. Novel antioxidants zolimid and AEOL11201 ameliorate colitis in rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2001;46:2222–2230. doi: 10.1023/a:1011975218006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang C, Gu H, Zhang W, Herrmann JL, Wang M. Testosterone-down-regulated Akt pathway during cardiac ischemia/reperfusion: A mechanism involving BAD, Bcl-2 and FOXO3a. J. Surg. Res. 2010;164(1):e1–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kerksick C, Taylor LT, Harvey A, Willoughby D. Gender-related differences in muscle injury, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008;40(10):1772–1780. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817d1cce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexander E., Jr Global Spine and Head Injury Prevention Project (SHIP) Surg Neurol. 1992;38(6):478–479. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhote VV, Balaraman R. Gender specific effect of progesterone on myocardial ischemia/ reperfusion injury in rats. Life Sciences. 2007;81(3):188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein DG. Brain damage, sex hormones and recovery: A new role for progesterone and estrogen? Neurosciences. 2001;24(7):386–391. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01821-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross S, Brown J, Dupre J. Hypersecretion of gastric inhibitory polypeptide following oral glucose in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 1977;26(6):525–529. doi: 10.2337/diab.26.6.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura T, Imamura K, Abe Y, Yoneda M, Watahiki Y, Makino I. Gastric functions in diabetics: gastrin responses and gastric acid secretion in insulin induced hypoglycaemia. J Japan Diab Soc. 1986;29:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feldman M, Schiller LR. Disorders of gastrointestinal motility associated with diabetes mellitus. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1983;98(3):378–384. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]